6.2 Latissimus Dorsi Flap

Principles

The discovery and use of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap for breast reconstruction during the early and mid-1970s by German plastic surgeons (Mühlbauer and Olivari) revolutionized the outcomes achievable in breast surgery. This comparatively reliable surgical procedure finally made it possible to obtain adequate skin and muscular coverage for the mastectomy defect on the chest wall, thus allowing good or very good restoration of the size, shape, and consistency of the breast.

Since then, numerous surgeons have refined the surgical technique further. The first edition of this book described different sites for the skin island. Various dissection techniques have also been described for complete or partial muscle transfer, as well as perforator flap dissection. Endoscopically assisted muscle harvesting is a further option. The present text focuses on the most commonly used surgical technique—latissimus dorsi transfer with a skin island for immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.

Some surgeons also use the latissimus dorsi to replace lost volume. Usually, however, it is combined with an implant, due to inadequate flap volume and in order to avoid a very long scar on the back. What this means, however, is that the procedure combines the disadvantages of a donor-site defect with those of an implant. It is important to recall this when considering whether to use a latissimus dorsi flap for reconstruction. The tendency of the latissimus dorsi to shrink should also be taken into account when planning the amount of tissue needed for reconstruction. Within 6–12 months, the muscle atrophies by about 50 %. The only truly stable portion of the transplant is the dermal fat flap, which is transferred with the muscle. This has the following effects on the surgical procedure:

If a combined latissimus/implant reconstruction is planned, the entire muscle has to be dissected and transferred to cover the implant.

If autologous tissue reconstruction is planned, partial transfer of the latissimus dorsi flap or use of a perforator flap may be considered, if the surgeon is comfortable with these techniques.

Anatomy of the Latissimus Dorsi Flap

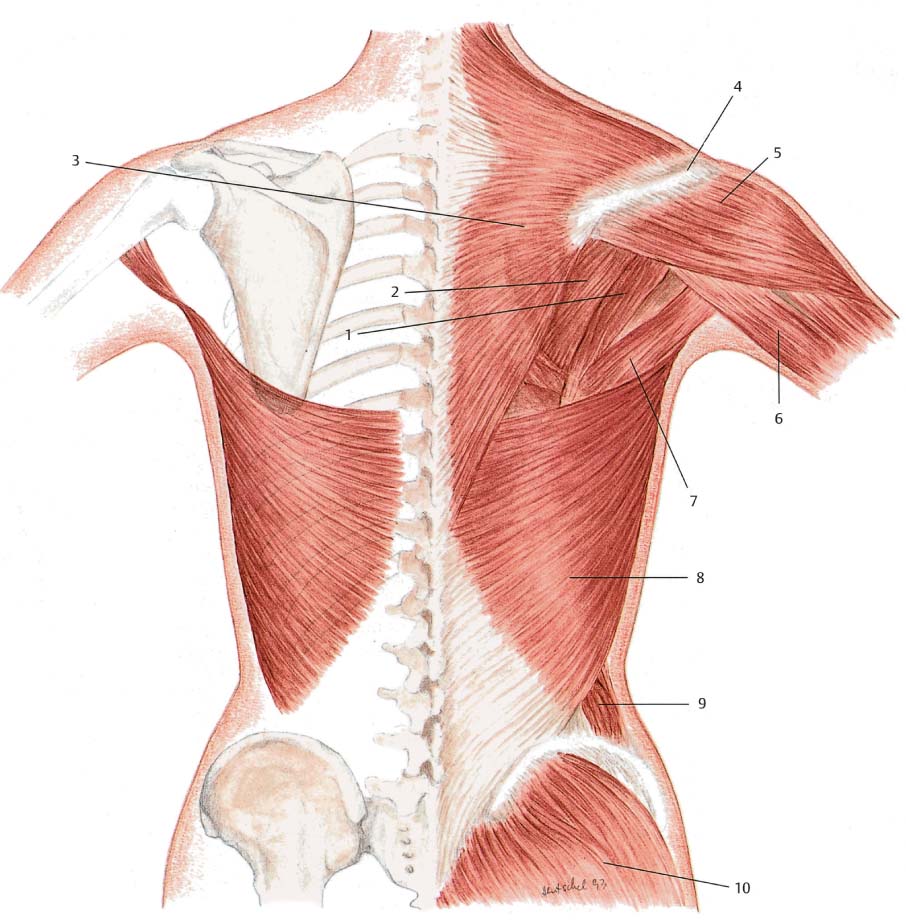

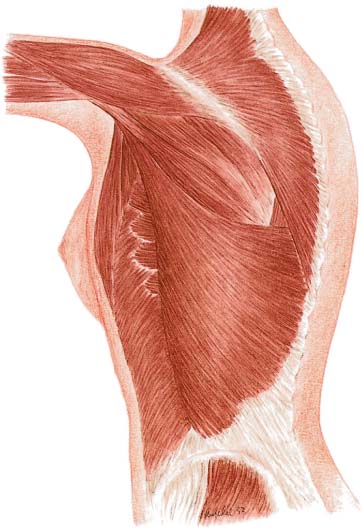

The latissimus dorsi is a large, triangular muscle that fans out over the back. It arises from the spinous processes of the lower six thoracic and the five lumbar vertebrae, the sacrum, and the posterior iliac crest. Some fibers also originate from the lower three or four ribs and sometimes from the inferior angle of the scapula. At the level of the inferior angle of the scapula, the muscle fibers converge toward the axilla, where they are in close contact with the teres major and thus contribute to the posterior axillary fold. The latissimus dorsi then rotates laterally and anteriorly around the teres major toward its insertion. Its tendon, which is 3 cm wide, inserts on the floor of the bicipital groove of the humerus. The teres major is the main muscular component in the posterior axillary fold, and the fold is therefore largely preserved if the latissimus dorsi is transposed anteriorly ( Figs. 6.10, 6.11 ).

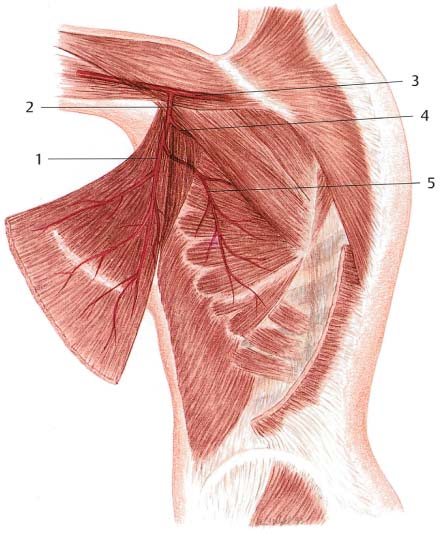

The arterial supply is provided by the thoracodorsal artery, the terminal branch of the subscapular artery. The thoracodorsal artery is accompanied by two companion veins and the thoracodorsal nerve. The thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle penetrates the inferior surface of the latissimus dorsi 10–12 cm below the axillary artery and 2.5–3.0 cm from its lateral border after traveling through the posterior axilla along the lateral side of the serratus anterior. The thoracodorsal artery measures 1–2mm in diameter.

Before the thoracodorsal artery enters the latissimus dorsi, it gives off the serratus branch, which enters the outer side of the serratus anterior. Perforating myocutaneous branches pass through the muscle to supply the overlying skin, which can be dissected to form a skin island. Additional blood supply is provided by the intercostal arteries near the origin of the muscle.

If the normal blood supply to the latissimus dorsi is disrupted due to transection of the thoracodorsal artery, the muscle is supplied by the serratus branch, which is fed by intercostal arteries and collateral vessels of the serratus muscle. This situation is not optimal, but the supply is sufficient for the myocutaneous flap. The thoracodorsal artery and serratus vessels are normally preserved when the latissimus dorsi is used for breast reconstruction. The muscle can be rotated around its neurovascular bundle in the posterior axillary fold and positioned on the anterior chest wall.

Familiarity with the anatomy of the intramuscular courses of the vessels and branches is essential for the optimal use of this technique. The largest branch courses vertically, parallel to the vascular pedicle and about 3 cm inside the lateral border of the muscle, as shown in Fig. 6.12 . This is where the largest side branch of the thoracodorsal artery courses, and thus the best vascular supply can be expected in the overlying skin island.

The skin island can also be well supplied by other vessels that branch off the vascular pedicle radially. The vascular pedicle is very long, and the vessels enter the muscle somewhat distal to its insertion; it is therefore possible to divide the latissimus dorsi at its insertion without disrupting its supply, if necessary, to facilitate flap rotation. If the main stem of the thoracodorsal artery is severed during mastectomy with axillary lymph-node dissection, the latissimus dorsi can still be supplied by the serratus branch and its collateral circulation. Special care has to be taken to preserve the serratus branch when rotating the latissimus flap. This may limit flap rotation, but it is still possible to transfer it anteriorly and attach it to the tendon of the pectoralis major in order to reconstruct the anterior axillary fold.

Indications for a Latissimus Dorsi Flap

In view of the versatility of the latissimus flap, the reliability of the surgical procedure, and the low morbidity at the donor site, the flap has come to be regarded as an excellent technique for breast surgery. Originally used for defect coverage on the thorax, the latissimus flap is now used in immediate and delayed reconstruction, as well as in breast-sparing cancer treatments. It is now most commonly used in delayed breast reconstruction. Information on additional indications for it is given in the relevant sections.

The latissimus flap for breast reconstruction is now mainly used for aesthetic rather than medical reasons. Radical mastectomy, which involves loss of the pectoralis major, was a compelling and ideal indication for using a latissimus flap, as its fan-shaped structure closely resembles that of the pectoralis major. However, with the methods currently used for mastectomy (in the modified radical operation), sufficient skin and muscle tissue is now usually preserved, so that implant reconstruction is generally possible. This may change with the current increase in the use of postmastectomy irradiation of the chest wall (see Chapter 11).

In any event, if the skin envelope is very taut and the subcutaneous tissue is thin, the latissimus flap is an outstanding option for achieving an aesthetically pleasing reconstruction result that will remain stable over time. Capsular contracture rates are also lower than with implant-only reconstruction, due to better soft-tissue coverage.

The indications for using a myocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap for breast reconstruction after modified radical mastectomy are based on individual anatomical factors, as well as the patient’s desire for a highly aesthetic reconstruction.

The anatomical factors required are thin soft-tissue coverage, an irradiated anterior chest wall, previous pectoralis major re-section or partial resection, a rather ptotic or moderately-sized contralateral breast, unsuccessful primary implant reconstruction, or (now rarely) radical mastectomy. In patients with borderline indications—i. e., with sufficient soft-tissue coverage and a rather small contralateral breast, in whom implant reconstruction would also be possible—it is necessary to weigh up the value of aesthetic considerations against the complexity of the operation and the creation of a donor-site defect in a discussion with the patient. In general, the more difficult the reconstructive procedure, the better the aesthetic success—also in terms of the long-term results, since the rate of capsular contracture after implant-only reconstruction is higher than in combination with latissimus reconstruction (see above).

It can also be difficult to determine whether a latissimus flap or autologous tissue transfer from the lower abdomen is most appropriate. Ultimately, of course, the decision has to be based less on the surgical expertise available at a given institution than on the patient’s individual physical situation. Nevertheless, the higher rate of complications and morbidity also need to be taken into account when establishing the indication. If autologous reconstruction using lower abdominal tissue is regarded as the method of choice, an indication for a latissimus dorsi flap can be established depending on whether there is enough excess skin and fatty tissue on the lower abdomen, or depending on the aesthetic situation in the abdominal wall. The contralateral breast volume can also be a factor in the decision. Abdominal flap reconstruction is more suitable for reconstructing large or very large breasts, as well as breasts with severe ptosis. The latissimus flap tends to be more suitable for reconstructing small or moderately-sized breasts.

Contraindications include damage to the latissimus dorsi due to previous surgery—for instance, after anterolateral thoracotomy or injury to the neurovascular bundle during axillary dissection. The latter is very rare, and it is not necessary to routinely expose the neurovascular bundle. If the patient is unwilling to accept the resulting scar on the back, it is of course a further contraindication.

Disadvantages of this procedure include the relatively lengthy operation, partly due to the need to reposition the patient during surgery; the additional scar; and placement of a portion of skin that may differ considerably from the surrounding breast skin with regard to texture and color (creating a “patch effect”).

Preoperative Planning

Assessment of the Latissimus Dorsi

Prior to surgical planning, it is necessary to assess whether the latissimus dorsi is intact. The latissimus dorsi pulls the arm backward and downward and produces medial rotation. Various tests of muscle function may be useful.

The surgeon supports the abducted arm, palpates the lateral portion of the latissimus dorsi, and instructs the patient to press the arm down. This action makes the lateral border of the latissimus easy to palpate. If the muscle is denervated, tension in the muscle will cause the inferior angle of the scapula to move upward. This sign of asymmetry is particularly clear if the patient places her hands on her hips and turns them inward. The muscle is also readily seen when the patient presses her hands firmly against each other. Arteriography can provide reliable information about the thoracodorsal artery, although this by no means forms part of the routine procedure. In 99 % of patients, the flap will still be viable if the serratus collateral vessels are preserved. Although denervated muscle is atrophied and thinner, successful transfer of the skin flap is possible.

Assessment of the Mastectomy Defect

In delayed reconstruction, it is essential to transfer a sufficiently large skin island in order to recreate the original breast shape. The amount of skin needed depends on the size of the mastectomy defect, as well as the shape and size of the contralateral breast.

Flap width is relatively easy to determine. It is the difference between the measurements of the contralateral breast (sternal notch-to-nipple, nipple–inframammary fold) and the amputated breast (sternal notch–inframammary fold) ( Fig. 6.2 ). When a latissimus flap is used, the difference should not exceed 6–8cm. Wider defects may be difficult to close. The length and width of the skin island are correlated with each other. For a skin island measuring 6–8 cm in width, the length is generally 14–16 cm. This can also be assessed by measuring the greatest width of the unoperated breast. In contrast to autologous tissue reconstruction using a lower abdominal flap, there are limitations on the skin island that is available over the latissimus dorsi. (It should be noted that experience shows that there is never too much skin flap available; there always tends to be too little.)

Strategic placement of the skin island in the mastectomy defect is a key factor in delayed breast reconstruction. Assessing the shape of the remaining breast is therefore important in achieving symmetry. Most patients undergoing the procedure no longer have firm, youthful breasts, but rather tend to have ptosis, with the greatest fullness inferolaterally. Viewed in profile, the superior slope of the breast becomes gradually more concave as it approaches the nipple as the point of maximum projection, while the lower pole is markedly convex. The most pronounced curve in the breast is thus along the relatively short distance from the inframammary fold to the nipple.

An abstract diagram of the breast profile would resemble a right-angled triangle projecting onto the mastectomy defect, with its long limb lying on the skin ( Fig. 6.14 ). As the figure illustrates, the shape of the breast is strongly determined by the fullness of the lower pole.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree