Pathology.

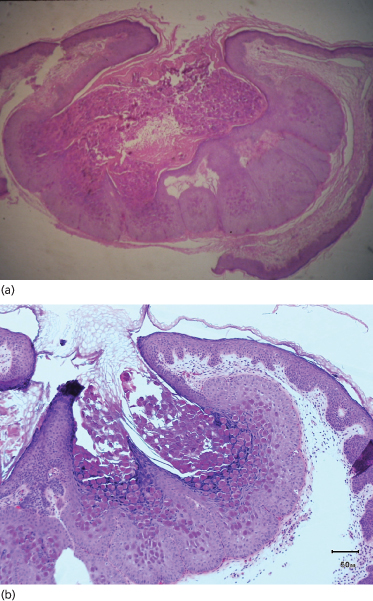

The virus enters the basal keratinocytes, where it causes an increase in cell turnover that extends to the suprabasal region. Higher in the stratum spinosum, the mitotic rate decreases as viral DNA synthesis increases. Proliferating cells within the follicular epithelium in particular form lobulated epithelial masses compressing the dermal papillae. However, the basal layer is not disrupted. Cytoplasmic aggregations of viral material appear as large hyaline bodies (molluscum bodies), and these eventually destroy the cells, particularly at the centre of each lobule. In a fully developed lesion, a cavity develops in which there are large numbers of molluscum bodies (Fig. 46.2). Little inflammatory infiltrate is seen in the adjacent dermis, although in chronic molluscum a granulomatous infiltrate may occur, possibly secondary to the discharge of papule contents into the upper dermis [31]. Scanning electron microscopy revealed a number of different gross morphologies of molluscum but all had a dense distribution of small protrusions with similar ultrastructure [32].

Fig. 46.2 (a, b) H & E of a fully developed molluscum lesion. Proliferating cells within the follicular epithelium form lobulated epithelial masses. Cytoplasmic aggregations of viral material appear as large hyaline bodies (molluscum bodies).

Immune Response

Good correlation was found between the presence of antibodies to MCV and clinical infection [33,34]. More recently, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was found to be specific and sensitive in the detection of antibodies to MCV-1 and -2 [35]. However, as with viral warts, it seems that depressed cell-mediated immunity (Th1), secondary to anti-inflammatory virulence factors produced by the MCV, rather than humoral immunity (Th2) is of greater importance in disease control [36]. Furthermore, MCV may evade detection and destruction by encoding proteins homologous to CD150, which is involved in signalling pathways essential to viral immunity [37]. The pathological appearance of the papular stage of resolving molluscum shows a dense mononuclear cell infiltrate hugging the epidermis [38], suggesting that a cell-mediated immune mechanism is involved in this process. Nonetheless, there is evidence for alleviation of molluscum via humoral immunity [39] and through the ubiquitin-proteasome system and apoptosis [40].

Clinical Features.

An incubation period for MCV of 2 weeks to 6 months has been reported, with the published infection frequency occurring in late childhood between the ages of 8 and 12 years [41]. In 25 years of practice (TAS), the peak incidence appears to be between and including diaper age to early grade school.

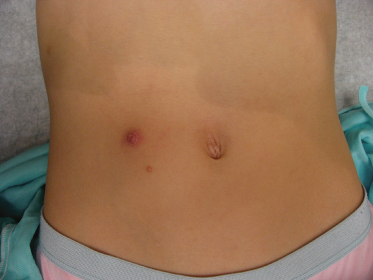

The morphology of an individual lesion is a dome-shaped papule, flesh coloured or pearly with an umbilicated centre (Fig. 46.3). Lesions vary in size from 1 to 10 mm although occasionally giant lesions are seen (primarily in the setting of HIV infection). Growth occurs over several weeks and eventually spontaneous remission will ensue. The spontaneous remission is heralded by inflammation, suppuration and crusting (Fig. 46.4) which destroys the lesion, leaving a small atrophic scar. Unlike varicella, the molluscum pox scar is transitory. Most cases of molluscum resolve within 6–9 months, but they can occasionally persist for several years. However, studies on children in Fiji show that no individual lesion persists for more than 2 months. In rare cases, primarily in the setting of immunodeficiency, widely disseminated and grossly disfiguring molluscum can occur in children (see Fig. 46.1) [42].

The lesions are often distributed on sites of friction from clothing, e.g. around the neck, axillae or trunk; in one large epidemiological study, the trunk was the most commonly reported location for lesions, and half of the patients presented with lesions in more than one anatomical region (Fig. 46.5) [20]. In tropical climates, involvement of the limbs is more common. Molluscum does occur in the anogenital region too, but this does not necessarily signify sexual spread in children (Fig. 46.6). More unusual sites include the scalp and face, although the latter distribution is common in those infected with HIV [28]. On the soles and mucosal surfaces, the appearance is atypical [43–45]. Around 10% of patients develop eczema around the lesions, but this disappears as the infection resolves [46]. Ocular manifestations of molluscum include dermal lid lesions, conjunctival lesions, follicular conjunctivitis, intraocular lesions, and chronic conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis [47,48]. If left untreated, vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea may occur [49].

Diagnosis.

This is generally straightforward, but large solitary lesions in adults may occasionally be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma. Expression of a white cheesy substance by lateral pressure with forceps on an individual lesion is characteristic. In the immunosuppressed patient, cutaneous cryptococcal infection may mimic MCV infection. Herpes simplex virus (other than the vesicular form), human papillomavirus, benign naevi, fibrous papules, adnexal tumours, milia, juvenile xanthogranuloma, pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomatosis, histoplasmosis, sebaceous naevi, comedones, furuncles, syringomas, Penicillium marneffei infection, basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, and varicella-zoster virus should also remain in the differential [42,50].

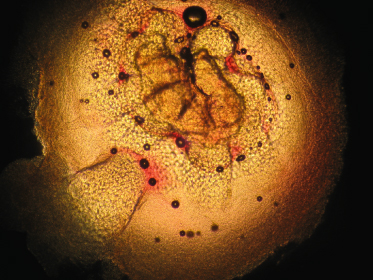

If diagnosis is not straightforward, other techniques may be of assistance. The easiest is a 10% KOH smear; simple light microscopy will demonstrate a papule with pseudo-saccules gathered symmetrically around the central pore. These pseudo-saccules have ever-increasing keratinocyte cell size as one looks from the base to the centre of the specimen (Fig. 46.7). In addition to KOH smear, biopsy, real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of swab samples (with pyrosequencing to differentiate between MCV-1 and MCV-2) [51], dermoscopy [52], and reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) [53] may also help to diagnose molluscum [50]. Dermoscopy reveals a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure in the centre surrounded by a crown of vessels [54]. RCM demonstrates a round, well-circumscribed lesion with central round cystic areas teeming with bright refractile material [53].

Fig. 46.7 KOH of a molluscum lesion. Low power. Note enlarged keratinocytes in pseudo-saccules leading to central pore.

Treatment.

In minor infections, it is reasonable to await spontaneous resolution, as this is least distressing to a child. There is a risk, however, of widespread cutaneous dissemination, discomfort, bacterial superinfection, acute inflammatory and chronic granulomatous reactions, and scar formation [19]. Spontaneously resolving lesions that become secondarily infected may require topical antiseptic application. Furthermore, left untreated, lesions can persist for several months to several years.

Active treatments for molluscum contagiosum include destructive methods, occlusion and cytotoxic, immune-modulating and antiviral preparations. Unlike varicella scars, molluscum scars are usually few and resolve completely. Molluscum scar keloids have not been noted in the literature.

Destructive Methods

Cryotherapy and Curettage.

Cryotherapy is a very effective therapy, inducing an ice ball in the lesion itself but not in the surrounding skin [41,55,56]. Application of EMLA cream (a eutectic mixture of prilocaine and lidocaine) 1 h before the procedure may facilitate treatment, which should not, however, be inflicted on an unwilling recipient! The use of phenol is not recommended because of scarring.

Curettage of single or a few lesions can be carried out once again using EMLA cream for local anaesthesia [57,58]. In one large study of four treatments, curettage was found to be the most effective, associated with the fewest adverse effects, and rated the highest patient satisfaction among patients and parents [19]. In this study curretage was done under general anaesthesia. Curretage had an 80% cure rate after one visit and 96% after two visits. Of note, in this same study, after two visits, topical cantharidin had an 80% cure rate, topical keratolytics had a 100% cure rate and topical imiquimod had a 96% cure rate. The latter three treatments did not require anaesthesia. Another curettage study found a high risk of treatment failure at weeks 4 and 8; risk factors for treatment failure were the number of lesions at day 0, the number of involved anatomical sites, and concomitant atopic dermatitis [59]. Furthermore, topical anaesthesia (e.g. EMLA) and occasionally systemic sedation may be required to perform the procedure.

Recently, a modified curettage technique has been described, involving first opening the epithelial surface of the lesion with a 30-gauge needle followed by gently scraping away the viral core with a fox curette [60]. This may be less traumatic and forceful compared with traditional curettage.

Cantharidin.

Cantharidin, a vesicant produced by Cleoptera beetles, has been widely used for molluscum contagiosum [61–63]. In a series of 300 children [61], it was shown to be extremely effective and well tolerated, applied carefully to each lesion with the blunt, wooden end of an applicator stick and rinsed off after 2–6 h, or earlier in the case of discomfort. Another study of 54 patients demonstrated a 96% improvement rate and a parental satisfaction rate of 78% [64]. Several applications may be required to successfully treat lesions. In our experience (TAS), two to six visits usually cure even the most widespread cases, and cantharidin has been used safely on the face and anogenital region without adverse events. Careful application of the cantharidin with a wooden applicator stick should be followed by immediate drying with a fan. Adjacent skin should be held apart until completely dry. If the skin is thin or in an intertrigenous area, less contact time is needed (2 h). The eyelids can be treated if the child is calm and can hold still with their eyes closed until the cantharidin is completely dried. Avoid the area immediately adjacent to the eye margins. Avoid at all costs dripping cantharidin into the eye itself. Baby shampoo is recommended to wash the area afterwards to avoid the eye-stinging sensation of regular soaps.

This preparation is not available in some countries, including the UK, and may have some adverse events, including exaggerated blistering, pain, pruritus, temporary hypopigmentation and secondary infection [64].

Keratolytics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree