40 Rhinoplasty in Children

Introduction

Traditionally, septorhinoplasty in children has been postponed until after puberty, unless there is a severe impairment of the nasal airway or a severe external deformity with obvious psychological impact on the young patient. In addition, there are specific indications such as acute nasal trauma, septal abscess, dermoid cyst, and progressive distortion of the nose that demand early surgical intervention.

In septal surgery, the submucosal septal resection (SMR) in the growing nose leads to saddle nose deformities and obvious growth disturbance of the nose and retroposition of the maxilla. These clinical observations 1 , 2 and experimental studies 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 confirm the importance of this clinical attitude.

The introduction of a more conservative submucosal septal correction (SSC) has led to a decline in the traditional restraint. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14

Some authors have stated that conservative septal surgery does not interfere with nasal growth. 14 , 15 Clinical studies in favor of SSC in the growing nose have lacked information about previous surgical intervention and have had too short followup periods. 15 , 16 , 17

However, longterm followup until after the puberty growth spurt has shown evident growth inhibition of the nose and maxilla. 18 , 19

Experimental studies in young, female, white New Zealand rabbits have shown comparable outcome with clinical observation with patients after nasal trauma and surgical intervention in childhood. 3 , 10 , 20 Not only septal surgery but also surgery of the cartilaginous vault will lead to growth inhibition and skeletal malformation. 21 Anatomical studies in fetal and infant nasal skeleton 22 have helped in the understanding of the impact on outgrowth of surgical intervention in specific stages of development of the nose. 23

The outcome of experimental surgery on the growing nose in rabbits, which is in concordance with clinical observations, gives scientific support to practical guidelines for rhinoplasty on the growing nose. There are distinct and relative indications for rhinoplasty in children. Especially in the latter, the surgeon has to weigh the possible growth inhibition against functional and/or aesthetic improvement.

In this chapter we discuss the theoretical background and experimental data of the morphogenetic function of the nasal septum for the outgrowth of the nose and maxilla, wound healing of the nasal cartilaginous skeleton, and new experimental developments to improve cartilaginous wound healing. Furthermore, the consequences of autogenous, homologous, and nonbiologic implant material in the growing nose are discussed. These experimental studies and clinical observations are the pillars for practical guidelines for rhinoplasty (approaches and techniques) on the growing nose. Finally, timing of the operation and general guidelines for septorhinoplasty in the growing nose are discussed, with illustration of specific clinical cases.

Theoretical Background

Clinical observations of development of the midface after nasal surgery or trauma have shown typical anatomical findings that are in concordance with experimental work done by the interdisciplinary working group of skull development in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32

Early experimental work by Urbanus and by Verwoerd-Verhoef on female, white New Zealand rabbits in producing an artificial cleft lip and palate resulted in the same growth disturbances as in cleft palate patients. The morphogenetic function of the nasal septum for the development of the midface and specific surgical procedures such as SMR and SSC have shown obvious similarities between the experimental animals and human beings. 24 , 25

One of the major problems after surgery of the cartilaginous skeleton is wound healing. Instead of cartilaginous healing, there is always a fibrous layer in between the surgically induced cartilaginous wound edges, which leads to distortion and or deviations of the cartilaginous structure based on the interrupted “interlocked stress.” 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37

Experimental Data of Surgical Procedures in the Growing Nose

Basic procedures in surgery of the septum and bony pyramid are resecting a basal strip, a vertical posterior chondrotomy, scoring, resection and reimplantation of autogenous material, and osteotomies. Analysis of the effect of these surgical intervention results in the following:

Resection of a part of the cartilaginous septum, resulting in a discontinuity of the septum, disturbs the morphogenetic function resulting in an underdevelopment (shortening and saddling) of the nose and retroposition of the maxilla. 3 , 5 , 10

Vertical incision (complete height of the septum) leads to deviation of the septal cartilage and/or duplicature (overlap of cartilage) and consequently moderate growth inhibition. 3 , 28 , 30 , 33

Removal of a basal strip results in lowering of the nasal dorsum with normal length and lowering of the cartilaginous dorsum and retroposition of the maxilla. 3 , 27

Reimplantation of autogenous (septal cartilage) material leads to overlap, deviation, and moderate growth inhibition, whereas homologous implants and nonbiologic material (Proplast) induce severe underdevelopment of the nose and retroposition of the maxilla. 10

The autogenous implant shows intrinsic growth. 10 , 30

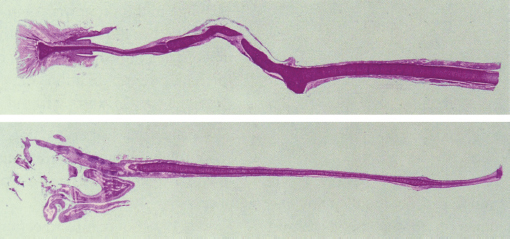

The use of an intraseptal splint of polydioxanone (PDS) foil results in significantly fewer deviations of the septum ( Fig. 40.1 ). 38

Resection of a central part of the thin area of the septal cartilage (e.g., septal perforation) does not lead to underdevelopment of the nose. 39

Surgical intervention of the cartilaginous vault leads to malformation of the nasal dorsum. 29

Mobilization and/or partial resection of the nasal bones and/or vomer does not lead to growth disturbance of the nose. 10 , 29 , 30 , 39

Development of the Anatomical Structures of the Nose during Childhood

There is a significant difference between the nose of a child and an adult regarding shape and underlying cartilaginous bony skeleton. Typical features of the child’s nose are:

Less projection of dorsum and tip

Larger nasolabial angle

Shorter dorsum

Flat nasal tip

Round nares

Short columella

The nasal skeleton of the infant differs considerably with that of the adult nose. 29 , 31

The cartilaginous skeleton forms a larger part, which makes the nose more flexible and less vulnerable for trauma.

The septal cartilage of the neonate reaches from the nasal tip to the interior skull base.

The upper lateral cartilages extend under the nasal bones over their total length and merge with the cartilaginous structure of the interior cranial skull base.

The perpendicular plate has not yet developed.

The T-bar structure of septum and upper laterals is directly based on the sphenoid, supports the nasal bones, and determines largely the contour of the dorsum.

The vomer is only rudimentarily developed.

During childhood, the nasal skeleton changes through ossification of the cartilaginous septum with the formation of the perpendicular plate that finally merges with the vomer at the age of 6 to 8 years, and the extension of the upper laterals to the anterior cranial base regress, leaving only an extension of 3 to 15 mm under the nasal bones in the adult stage.

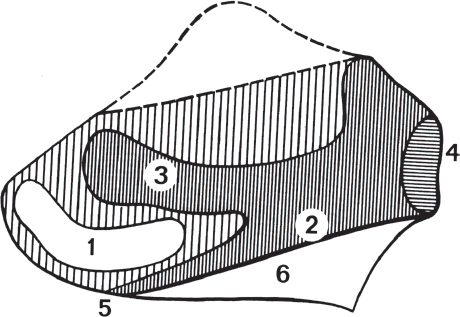

The specific pattern of difference in thickness of the cartilaginous septum, especially the thicker zones, diverging in the sphenospinal and sphenodorsal zone plays an important role in normal outgrowth of the nose and maxilla ( Fig. 40.2 ). 22 , 23 , 39 , 40

The two growth centers increase the length and height of the bone (sphenodorsal zone) and outgrowth of the maxilla (sphenospinal zone). Trauma or surgical loss of one these two growth centers cause growth inhibition in a specific pattern. 31 , 39

Timing of the Operation

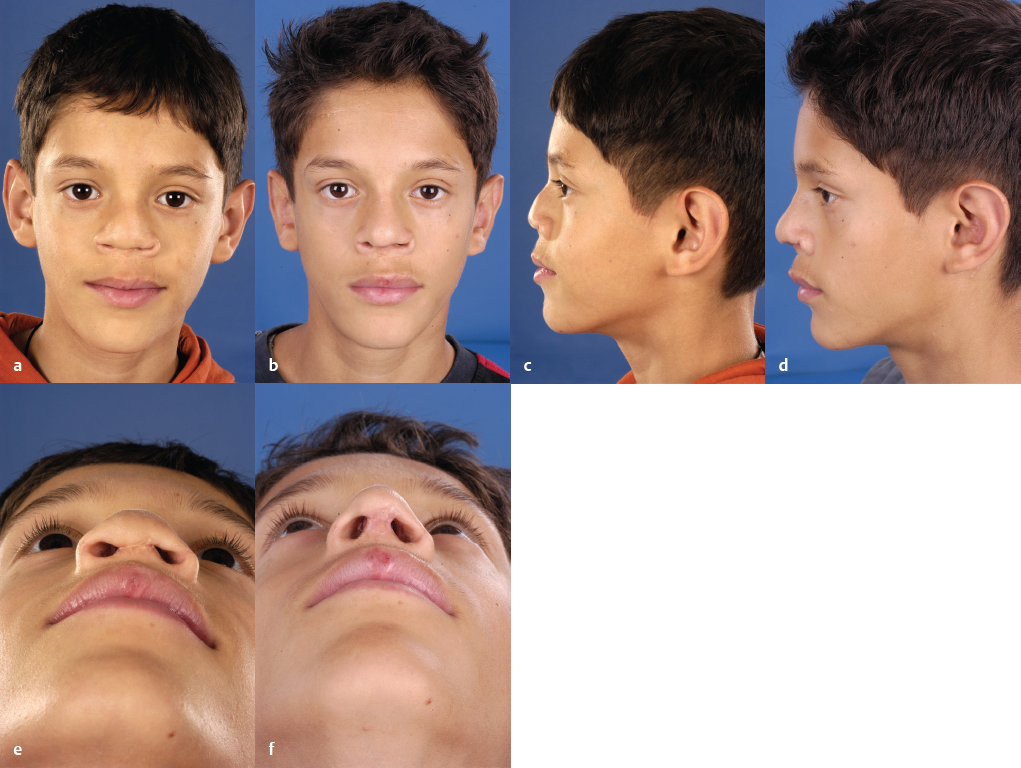

The adage to postpone septorhinoplasty until after the puberty growth spurt (to prevent growth inhibition and redeviation) is still valid. However, severe functional and aesthetic sequelae ask for surgical intervention ( Fig. 40.3 ). Distinct indications for immediate intervention are acute nasal trauma, septal abscess, and malignancies, whereas severe septal deviations causing nasal airway obstruction, benign tumors such as dermoid cysts, highly progressive distortion, and stigmatic deformities such as cleft lip–nose stigmata ask for surgery before the end of the puberty growth spurt.

With the more sophisticated modern techniques and great demand by patients (and/or parents), there is a tendency to perform septorhinoplasty before the final (puberty) growth spurt.

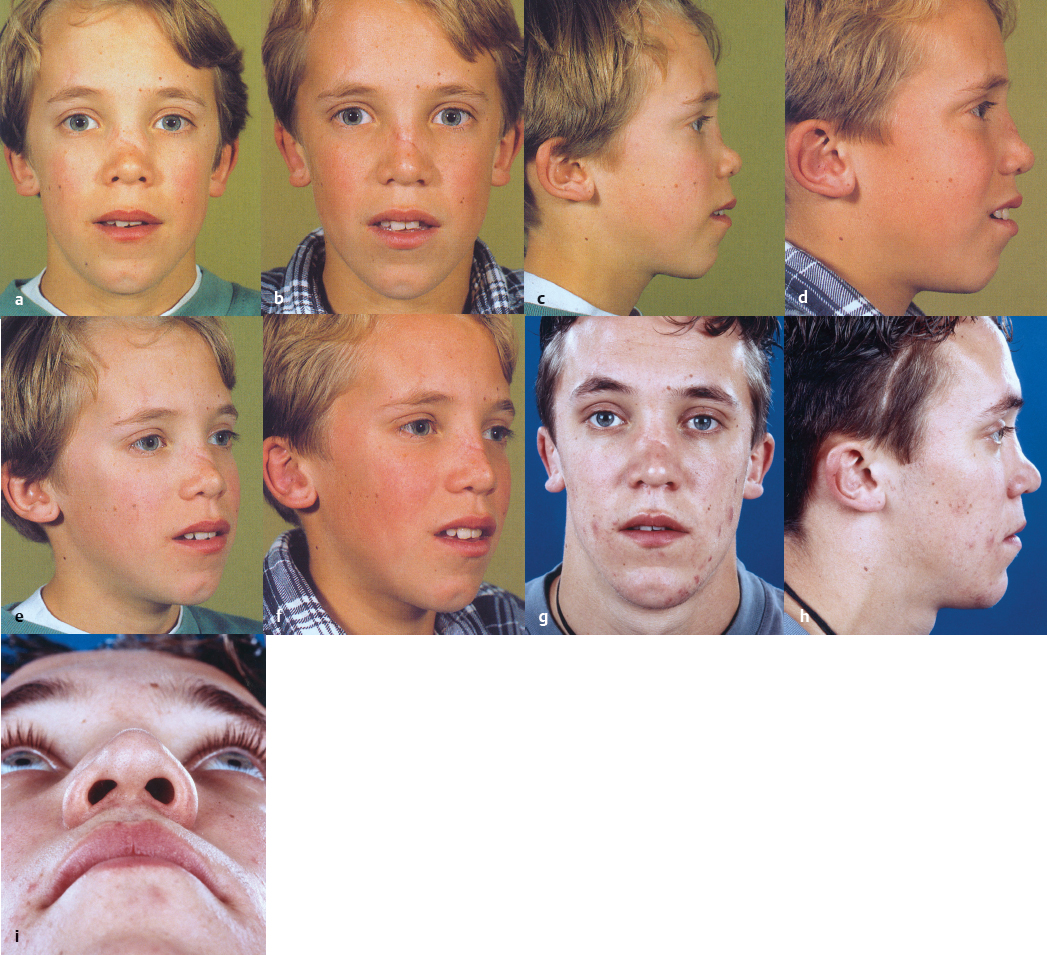

Short followup has given rise to misleading statements in the literature that septorhinoplasty in children does not have consequences for the outgrowth of the nose and maxilla. There are two significant growth spurts: the first two postnatal years and during puberty when the nose grows faster than during the other periods of life. Consequently, surgery performed in the period between growth spurts can disguise a possible surgically induced growth disturbance until the final growth spurt ( Fig. 40.4 ).

The surgeon should be aware that even after the final growth spurt there can be some further growth of the septum up to the age of 25 that can lead to late postsurgical distortion. Therefore, parents and patients should be informed that late results cannot be predicted, and the possibility of revision surgery should be discussed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree