35 Management of the Bony Nasal Vault

Introduction

An important challenge to the surgeon wishing to master modern rhinoplasty is the consideration of nasal function in addition to traditional aesthetic concerns. The importance of nasal function is evidenced by the proposition that the distinguishing features of the human nose arose in Homo erectus in response to the need for more moisture conservation. 1 Recognition of nasal function is particularly important to the surgeon manipulating the bony skeleton of the nose. While suboptimal aesthetic results may occur with either inadequate or inappropriate mobilization of the nasal bony cartilaginous framework, significant reduction of the nasal airway may also occur. A number of techniques are available to appropriately mobilize and reposition the bony nasal vault. Herein we review our experience with a variety of techniques and consider some special situations.

Anatomy

External Landmarks and Soft Tissue Components

Requisite to the use of the techniques described here is an understanding of the bony anatomy of the nose and its relation to the external nasal contour. The external contour of the upper third of the nose is defined by the two sidewalls, the dorsum, and the nasofrontal angle. 2 , 3 The nasion is the bony junction between the frontal and nasal bones. The nasofrontal angle is the external landmark identifying the deepest or most posterior portion of the nasal dorsum and may lie several millimeters inferior to the nasion. The rhinion is the osseocartilaginous junction of the nasal bones to the superior edge of the upper lateral cartilages.

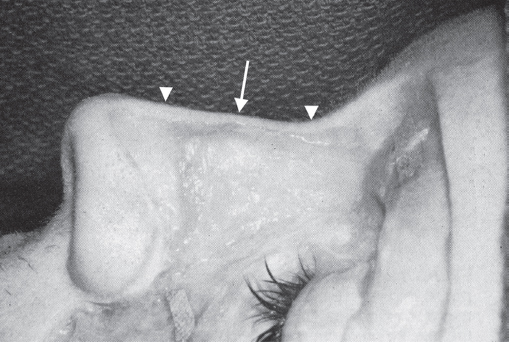

The external appearance of the nose is affected by both the bony cartilaginous framework and the shape and consistency of components of the overlying soft tissue envelope. This soft tissue varies in thickness over the nasal bones. As shown in Fig. 35.1 , the nasal skin is thicker superiorly and inferiorly and quite thin over the central nasal rhinion. 2 Thus, surgery on the nasal profile must compensate for this to avoid a “saddle nose” appearance. For example, a slight hump must be left at the bony rhinion if a straight soft tissue profile is desired.

Bony and Cartilaginous Framework

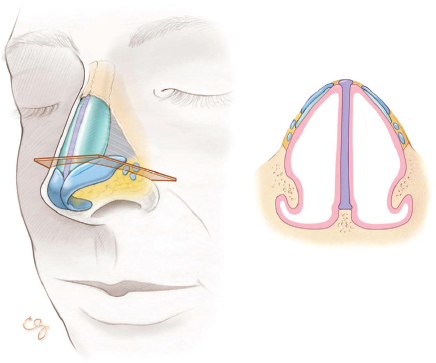

The nasal bones are paired structures that attach superiorly to the frontal bone and laterally to the nasal process of the maxillary bones. These structures together form the bony nasal vault. The keystone area is the junction of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid with the nasal bones at their inferior edge in the midline. This is an important area as destabilization here in the setting of aggressive septoplasty can lead to a saddle nose deformity. The sidewalls are formed by the nasal bones themselves and the frontal process of the maxilla. The area of bone just lateral and superior to the inferior turbinate supports the nasal wall and thus is preserved in osteotomy, as discussed later in this chapter ( Fig. 35.2 ). The nasal bones are thin inferiorly and become thick superiorly. 2 , 4 This is demonstrated by transillumination of the skull ( Fig. 35.3 ). The variable thickness of the bony structures of the nose has implications for osteotomy placement, as discussed later in the chapter.

The septum supports the nose below the inferior edge of the nasal bones. The septum and upper lateral cartilage complex provide the skeletal component of the lower nasal dorsal profile. Preservation of adequate (> 1 cm) dorsal and caudal struts of septum during septoplasty is paramount in preservation of this profile. In the setting of dorsal hump reduction, the amount of septum to be removed during hump reduction must be taken into account. For this reason, the authors regularly perform hump reduction and medial osteotomies prior to removal of any septal cartilage, if septoplasty is being performed concurrently.

Basic Surgical Techniques

Hump Reduction

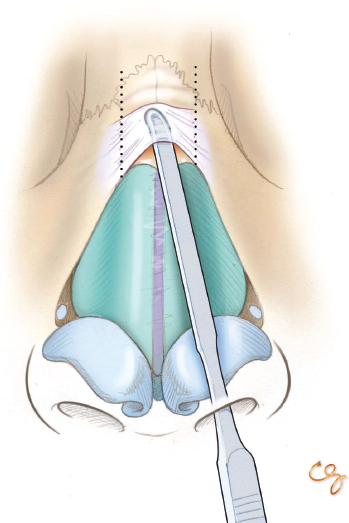

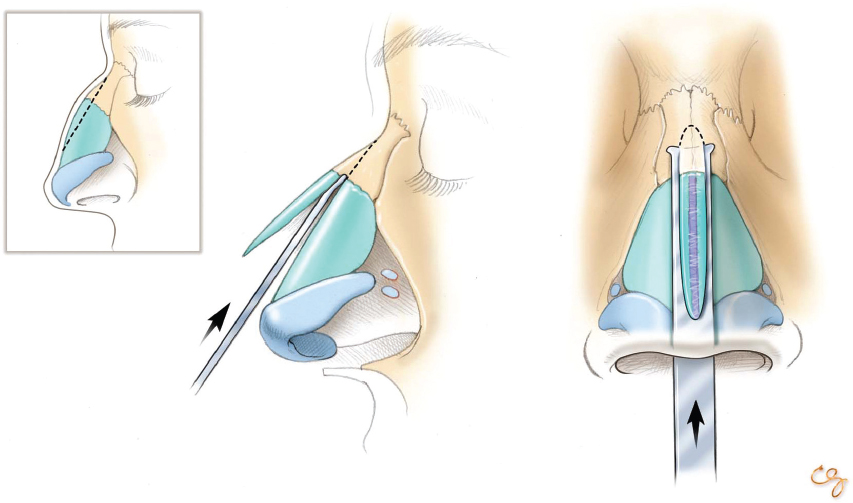

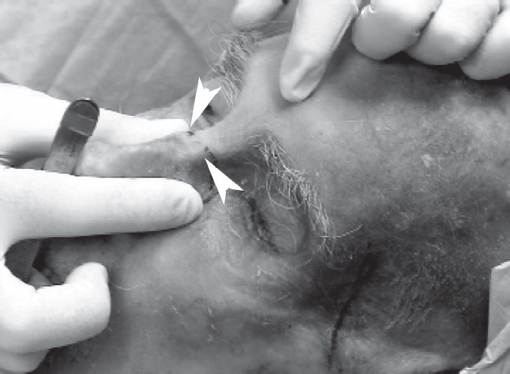

The soft tissue envelope is elevated from the bony cartilaginous framework up to the level of the nasofrontal angle (via incisions described elsewhere in this text). Care is taken to undermine conservatively, limiting dissection to the dorsum only, yet widely enough to permit adequate hump reduction and subsequent skin redraping ( Fig. 35.4 ). Although adequate exposure is obtained to perform the desired reduction or refinement of the profile, as much soft tissue support is preserved as possible. This soft tissue support helps reduce the risk of producing a flail nasal bone after osteotomy. Either an osteotome or a rasp can be used to lower the dorsum, depending on the surgeon’s experience and preference. In general, an osteotome may be used for larger humps and a rasp for smaller reductions and refinements. To remove larger humps, a conservative correction is performed with a double-guarded osteotome ( Fig. 35.5 ). Refinements are then made with a tungsten carbide pull rasp. The rasp is angled slightly obliquely off the midline to avoid avulsing the upper lateral cartilages from the undersurface of the nasal bones. Removal of a dorsal hump creates a so-called open roof deformity, necessitating osteotomies for closure ( Fig. 35.6 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree