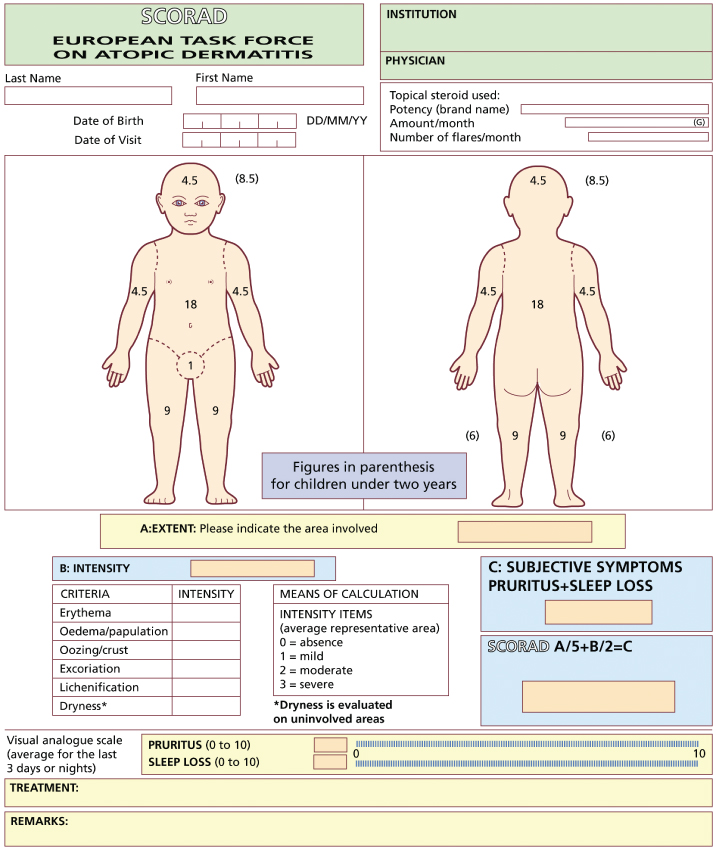

Fig. 29.2 SCORAD evaluation sheet.

Reproduced from Charman & Williams 2000 [5] with permission from American Medical Association.

As with most ‘objective’ atopic dermatitis indices, inter- and intraobserver variation can occur, with lichenification and disease extent being among the most difficult features to score consistently [9,12]. When SCORAD is used in black children, assessments of erythema can be difficult and can lead to underestimation of disease severity; this is also likely to occur with other scoring systems in which erythema is included as a severity parameter [22]. Training has been recommended before using the index, and is freely available on the SCORAD website (http://adserver.sante.univ-nantes.fr). In addition, a computer software program called ScoradCard® has been developed to assist with SCORAD assessments (http://www.tpsproduction.com) [23]. Assessments can be made in less than 10 min, after training [12,20].

SCORAD is a composite score, and combining both objective and subjective measurements made by both the physician and the patient may be seen as disadvantageous, although the measurements of signs, symptoms and disease extent can easily be presented separately if required. It has been recommended that only the objective components of the SCORAD index (disease intensity and extent) be used for inclusion and categorization of patients into clinical trials, but that the complete index (including subjective criteria) should remain the major follow-up and end-point study criterion [9,10]. A self-assessed patient-oriented version of SCORAD has recently been described (PO-SCORAD) [24]. The PO-SCORAD has undergone preliminary validation, although some clinical signs were found to be difficult for patients to measure accurately, particularly disease extent, lichenification, and oedema/swelling of the skin. An illustrated document has been proposed to accompany the index in further validation studies.

Eczema Area and Severity Index

The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score was described in 1998 as a new tool for assessing atopic dermatitis severity and response to therapeutic interventions [8,25]. The index involves an assessment of the average intensity of four clinical signs – erythema, induration/papulation, excoriations and lichenification (0–3) – each assessed at four defined body sites (Table 29.2). Disease extent is also assessed in each of the four regions on a scale of 0–6. The total score for each body region is obtained by multiplying the sum of the severity scores of the four key signs by the area score, and then multiplying the result by a constant weighted value. The constant weighted value represents the contribution of each body region to the total body surface area, with a modification for young children. The sum of the scores for each body region gives the EASI total (maximum score 72).

Table 29.2 The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI).

| Body region | EASI score in patients ≥ 8 years | EASI score in patients ≤ 7 years |

| Head/neck (H) | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.1 | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.2 |

| Upper limbs (UL) | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.2 | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.2 |

| Trunk (T) | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.3 | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.3 |

| Lower limbs (LL) | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.4 | (E I Ex L) × area × 0.3 |

EASI = sum of the above four body region scores.

E, erythema; I, induration/papulation; Ex, excoriation; L, lichenification.

Area is defined on a seven-point ordinal scale: 0 = no eruption; 1 = <10%; 2 = 10–29%; 3 = 30–49%; 4 = 50–69%; 5 = 70–89%; 6 = 90–100%.

The index has been widely used and validated against other measures of disease activity in trials involving children and adults [26–28]. EASI and SCORAD scores have shown high correlation in children and adults [18,19]. Reliability studies have shown reasonably good inter- and intraobserver agreement, with induration/papulation assessments showing the most interobserver variability [18,25]. A self-assessed version of the index (SA-EASI) has been proposed for parents or caregivers of patients under 12 years of age, showing reasonable correlation between parental and physician-assessed total scores but poor agreement between individual components of the scale [29,30].

The EASI does not attempt to include symptoms in the overall score, and these should be measured separately. The assessment of disease extent forms an important integral part of the index, requiring measurement in four sites that can be technically very difficult and time consuming. The index also assumes that disease severity is a product of disease intensity and area affected, whereas in real life disease severity as perceived by the patients may be more dependent on the site affected, e.g. face, hands, than the percentage area per se. Therefore, as with the SCORAD index, meaningful interpretation is easiest if the components of the index are presented both separately and as part of the composite index.

Other Scoring Systems Based on Clinical Signs

At least 15 other objective scoring systems based on the measurement of clinical signs have been described for atopic dermatitis over the years, and are discussed in detail in reviews [4,5]. Whilst some of these scales have useful attributes and may provide a good measure of disease activity, others have been inadequately tested and have made interpretation of patient outcomes difficult. Currently there is less information available to recommend widespread use of these scales, and they have generally been superseded by the SCORAD index and EASI for monitoring changes in disease activity in clinical trial work.

For everyday clinical use or as a prescreening tool for trial entry, the Three Item Severity (TIS) score remains a useful simple index. The TIS score is based on the assessment of three clinical signs from the SCORAD index – erythema, oedema/papulation and excoriations (maximum score 9) [31]. These three clinical signs have independently been shown to be good predictors of atopic dermatitis severity from the patients’ perspective [32]. TIS scores have shown close correlation with the SCORAD index, and fair interobserver agreement [6,10,31].

The Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis (SASSAD) index is a more complex but widely used score comprising an assessment of six clinical signs (erythema, exudation, excoriation, dryness, cracking and lichenification) measured at six defined body sites (arms, hands, legs, feet, head and neck, trunk), each on a scale of 0–3 (maximum score 108) [33]. As the clinical signs are measured at six body sites rather than a single representative site, the index provides an indirect estimate of disease extent without the need for precise measurement of body surface area involvement. Validity of the SASSAD index has been demonstrated in several trials involving children and adults [34–36], although reliability data are limited to one small study [37].

Rajka & Langeland’s scoring system [38] is another widely recognized scale measuring a combination of clinical course, intensity and disease extent (maximum score 9), to provide a broad indicator of long-term and current atopic dermatitis severity status. This score, and its modified version known as the Nottingham Eczema Severity Score [15,17,39], can be useful for epidemiological studies or for grouping patients for entry into clinical trials, but they lack the sensitivity to change needed for the majority of clinical trial work.

Other scales include the Assessment Measure for Atopic Dermatitis [40], Atopic Dermatitis Area and Severity Index [41], the Atopic Dermatitis Severity Index [19,42], the Basic Clinical Scoring System [13], the Four Step Severity Score (FSSS) [43], the Simple Scoring System [44], the Objective Severity Assessment of Atopic Dermatitis Score (OSSAD) [45] and the W-AZS [46].

Traditionally the objective measurement of clinical signs has been carried out by physicians, although there has been a recent trend to develop self-assessed objective scores, where patients or parents are asked to grade visible clinical signs such as redness and oozing at different body sites. In addition to the SA-EASI [29] and Patient-Oriented SCORAD [24] described above, this approach is adopted in the Atopic Dermatitis Quickscore (ADQ) [47]. Although theoretically such an approach allows more accurate long-term follow-up, in practice the grading of clinical signs can be time consuming and difficult for some patients, and correlations with physician-rated scores are variable.

Disease Extent

Measurements of disease extent have been used to monitor atopic dermatitis severity for many years, either as part of composite scoring systems such as the SCORAD index or the EASI or as separate outcome measures. The most widely recognized measurement technique is the ‘rule of nines’ in which 9% of the total body surface area is accounted for by the head and neck, each arm, the front and back of each leg, and the four trunk quadrants, with 1% for the genitalia. However, the wide range of techniques used to assess body surface area involvement reflects the difficulties involved, with over 20 different methods being employed in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) over recent years [6]. Atopic dermatitis is characterized by indistinct disease margins, making accurate and reliable assessments technically very difficult. Even in psoriasis, a relatively well-demarcated disease, difficulties in assessing disease extent have been recognized [48,49]. The complex three-dimensional shape of the human body adds to these difficulties, and even with two-dimensional schematic figure outlines, wide interobserver variation has been demonstrated [50]. In one study examining the reliability of body surface area assessments using six dermatologically trained observers, the percentage surface area measurements varied between 5% and 65% for one patient and between 13% and 100% for another [51]. Specific training in disease extent measurements may help; in a further study using photographs of patients with atopic dermatitis, the mean disease extent scores as assessed by 98 non-expert investigators ranged from 20% to 100% compared with a range of 45–60% among three experts who selected the photographs [12]. Patients also find it difficult to measure disease extent [24], although investigators have shown good agreement when translating patient-assessed area measurements (from figure drawings in the SE-EASI and Patient-Oriented SCORAD) into percentage area involvement scores [52].

Although the measurement of surface area involvement provides a convenient figure for physicians in therapeutic trials, clinical practice suggests that the precise percentage of skin involved may be less important in terms of disease severity than the actual body site affected. Although, broadly speaking, patients with more extensive disease have higher morbidity than those with limited disease, the relationship between morbidity and area is certainly not linear, and a small change in eczema extent over the hands or face may be much more important than a larger change over the trunk. As patients are unlikely to notice a change in disease extent of 1% over many areas of their body, this raises the question of whether physicians should be attempting to score disease extent so precisely. Presenting measurements of disease extent separately from measures of disease intensity and subjective scores allows these issues to be taken into account.

Measuring Patient Symptoms

Although patients’ symptoms are subjective, it is ultimately around the control of these symptoms that the treatment of atopic dermatitis revolves. As symptoms are self-rated by patients, regular assessments using diary records can be used to capture fluctuations in disease activity and potentially provide a more accurate long-term picture of the effects of therapy.

Itching (pruritus) is the most commonly measured symptom in recent clinical trials [6] and is one of the predominant symptoms that physicians take into account in routine clinical practice when making global assessments of disease severity [53,54]. Pruritus is most commonly measured by asking the patient to mark a score on a visual analogue scale (e.g. a 10 cm line) or simple ordinal scale, although more comprehensive itch questionnaires have been described [47,55,56]. In the clinical trial setting, nocturnal pruritus has also been measured using an infrared video camera and a wrist activity monitor [57–59]. Sleep loss is closely related to pruritus, and was the second most commonly measured symptom in a review of randomized controlled clinical trials of atopic dermatitis [6]. Sleep disturbance is usually recorded in a similar way to pruritus, but may be more difficult for the patients to assess accurately. Other symptoms such as soreness or discomfort are also important to patients but are less frequently measured in practice. Meaningful interpretation of symptom scores is difficult if the scores rated by patients are combined with measurements of clinical signs rated by physicians [60]. Therefore, when composite scoring systems such as SCORAD or the Patient-Oriented SCORAD are employed, the symptom data should also be presented separately wherever possible.

The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) is a useful patient-based scoring system incorporating seven symptoms shown to be of importance to patients (itching, sleep disturbance, bleeding, weeping, cracking, flaking, and dryness of the skin) [61]. The POEM is scored by patients (or parents) over a 1-week period, with a maximum possible score of 28. The measure has demonstrated good validity and repeatability in adults and children ranging from 1 year of age upwards, and further studies are currently underway to help categorize scores into mild, moderate and severe from the patients’ perspective.

Global Measures of Disease Severity

Although complex clinical scoring systems such as the SCORAD index provide a detailed way of scoring disease severity on a continuous scale that can then be subject to statistical analysis, translating how changes in the final score actually reflect disease severity, or interpreting the relevance of a change in score of 75 to 62, can be difficult. Global measures of disease severity are easily assessed by either the patient or the physician, and can provide a more pragmatic method of assessing disease severity. Although global measures of eczema severity are most commonly used in everyday clinical practice to monitor response to therapy, they are being increasingly used in RCTs, either to complement other outcome measures or as primary outcome measures [26,27]. In a review of RCTs for atopic dermatitis, an overall global severity assessment by the investigator or patients was performed at the end of the study in approximately one-third of trials [6]. In clinical trials, physicians’ global assessments are often based primarily on clinical signs, whereas global severity assessments made by patients will also take into account symptoms and psychosocial factors, and can provide a more realistic measure of the effectiveness of healthcare intervention. Various scales have been used, although simple three-point scales (worse, same, better) are usually too crude to be helpful, and a five- or six-point scale (exacerbation of disease, no change, slight improvement, moderate improvement, marked improvement or complete resolution) is probably optimal. As with more complex scales, intra- and interobserver variation may occur, although because of the broad categories, slight variations are less likely to affect the final score. The Investigators’ Global Assessment (clear, almost clear, mild, moderate, severe, very severe) is widely used in clinical trials, but the categories are open to interpretation [4,11].

Additional Measures of Disease Severity

Topical steroid requirements are sometimes monitored in clinical trials by weighing tubes of steroid preparations at the beginning and end of treatment. However, a variety of factors other than disease severity, such as application technique and topical steroid phobia, may influence steroid use, and such measurements can be used only as secondary outcome measures. Objective measures of skin hydration and transepidermal water loss [2,17,19] and biological parameters including serum eosinophil cationic protein, E-selectin and macrophage-derived chemokine have also been shown to change with eczema severity and may provide additional information on disease activity, although these measures cannot replace clinical and patient-based assessments [11].

Lack of Standardization of Outcome Measures

Despite the availability of validated scoring systems for measuring atopic dermatitis severity, a review of 93 RCTs published between 1994 and 2001 showed that only 27% of trials had employed a published clinical severity scale, with the remainder using either modified versions of published scales (14%) or un-named scales with few or no data on validity or reliability (59%) [6]. Patient symptoms and disease extent were recorded in 86% and 67% of trials respectively. However, quality of life was only measured in three trials (3%), despite increasing recognition of the importance of quality-of-life measurements in healthcare assessment, as discussed in the next section.

Overall, there was lack of consensus on which clinical features best reflected disease severity, with over 30 different descriptions of clinical signs being used across all scoring systems [6]. The situation has not improved since this review, with further scales being developed that have undergone limited testing [4]. Of the 20 named indices of atopic dermatitis severity currently available, only the SCORAD index, EASI and the POEM have been validated adequately enough to recommend their use in clinical trials and everyday practice [4,62].

References

1 Gutgesell C, Heise S, Seubert A et al. Comparison of different activity parameters in atopic dermatitis:correlation with clinical scores. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:914–19.

2 Holm EA, Wulf HC, Thomassen L et al. Instrumental assessment of atopic eczema: validation of transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, erythema, scaling and edema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:772–80.

3 Hanifin JM. Standardized grading of subjects for clinical research studies in atopic dermatitis: workshop report. Acta Dermatol Venereol (Stockh) 1989;144(suppl):28–30.

4 Schmitt J, Langan S, Williams HC. What are the best outcome measurements for atopic eczema? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1389–98.

5 Charman CR, Williams HC. Outcome measures of disease severity in atopic eczema. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:763–9.

6 Charman CR, Chambers C, Williams HC. Measuring atopic dermatitis severity in randomised controlled clinical trials: what exactly are we measuring? J Invest Dermatol 2003;120:932–41.

7 European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Dermatology 1993;186:23–31.

8 Tofte S, Graeber M, Cherill R et al. Eczema area and severity index (EASI): a new tool to evaluate atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1998;11(suppl 2):48.

9 Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labrèze L et al. Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index: consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1997;195:10–19.

10 Oranje AP, Glazenburg EJ, Wolkerstorfer A et al. Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis:the SCORAD index, objective SCORAD and the three-item severity score. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:645–8.

11 Gelmetti C, Colonna C. The value of SCORAD and beyond. Towards a standardized evaluation of severity? Allergy 2004;59(suppl 78):61–5.

12 Oranje AP, Stalder JF, Taïeb A et al. Scoring of atopic dermatitis by SCORAD using a training atlas by investigators from different disciplines. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1997;8:28–34.

13 Sprikkelman AB, Tupker RA, Burgerhof H et al. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of three scoring systems. Allergy 1997;52:944–9.

14 Pucci N, Novembre E, Cammarata MG. Scoring atopic dermatitis in infants and young children: distinctive features of the SCORAD index. Allergy 2005;60:113–16.

15 Hon KLE, Kam WYC, Lam MCA et al. CDLQI, SCORAD and NESS: are they correlated? Qual Life Res 2006;15:1551–8.

16 Hon KLE, Leung TF, Wong Y et al. Lessons from performing SCORADs in children with atopic dermatitis: subjective symptoms do not correlate well with disease extent or intensity. Int J Dermatol 2006;45(6):728–30.

17 Hon KLE, Wong KY, Leung TF et al. Comparison of skin hydration evaluation sites and correlations among skin hydration, transepidermal water loss, SCORAD Index, Nottingham Eczema Severity Score, and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008;9(1):45–50.

18 Rullo VEV, Segato A, Kirsh A et al. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of two scoring systems. Allergol Immunopathol 2008;36(4):205–11.

19 Holm EA, Wulf HC, Thomassen L et al. Assessment of atopic eczema: clinical scoring and non-invasive measurements. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:674–80.

20 Schäfer T, Dockery D, Krämer U et al. Experiences with the severity scoring of atopic dermatitis in a population of German pre-school children. Br J Dermatol 1997;137:558–62.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree