26 Avoidance and Management of Complications Following Lower Eyelid Surgery

Key Concepts

An understanding of the anatomy and function of the eyelids is necessary for safety and avoidance of complications.

It is important to appreciate the potential aesthetic and functional effects of lower lid surgery.

The surgeon should be able to perform a thorough preoperative evaluation of the patient considering lid surgery.

The canthal anchor is a critical aspect of lid surgery and plays a functional and aesthetic role.

The common complications of lower eyelid surgery are addressed and methods to avoid them are presented.

Introduction

Aesthetic eyelid surgery is consistently one of the top five plastic surgery procedures performed yearly.1 Lower eyelid aesthetic procedures are particularly effective at generating a more youthful appearance. The procedures are unique in that they have both aesthetic and functional consequences. If the procedures are performed well in the proper setting and on the right patient, beautiful and pleasing results can be obtained that maintain, and in some cases improve, proper lid function. Understanding the regional anatomy, performing a proper patient evaluation, and constructing a sound operative plan all play a significant role in avoiding complications in lower lid surgery. Nevertheless, complications do occur, and understanding how to recognize and treat them is crucial for positive outcomes.

Background: Basic Science of Procedure

The goal of lower lid aesthetic procedures is to restore a youthful appearance to the eyelid and maintain proper lid function. The youthful eye typically has smooth curves; an open, bright, and rested appearance; some degree of pretarsal lid show; a neutral or upward canthal tilt; and a lid–cheek junction that is smooth and without demarcation. There are many procedures for lower lid rejuvenation, and the most effective ones address each anatomical feature that contributes to an aged appearance ( Table 26.1 ). It is up to the surgeon to ascertain the patient′s desires and to conduct the physical exam and overall evaluation and to develop a surgical plan that will meet the patient′s expectations while minimizing the risk of complications.

Pertinent Anatomy

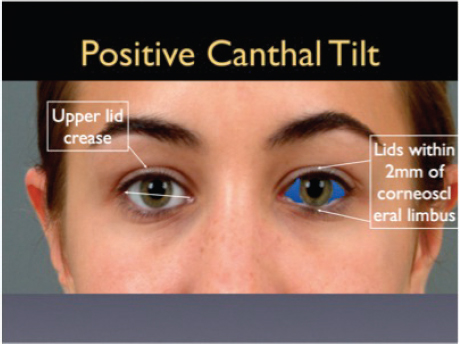

The lower eyelid is divided into three layers, commonly referred to as the outer, middle, and posterior lamellae. The outer lamellae is made up of skin and the underlying orbicularis muscle, the middle lamella is the orbital septum, and the posterior lamellae is made up of the lower lid retractors and conjunctiva. The aperture of the eye is based on how the lids frame the globe. Normal lid position covers 1 to 2 mm of the upper and lower corneoscleral limbus, creating the medial and lateral scleral triangles, the lateral being slightly larger in general. Furthermore, the youthful eyelid generally has an upward canthal tilt, but not always ( Fig. 26.1 ).

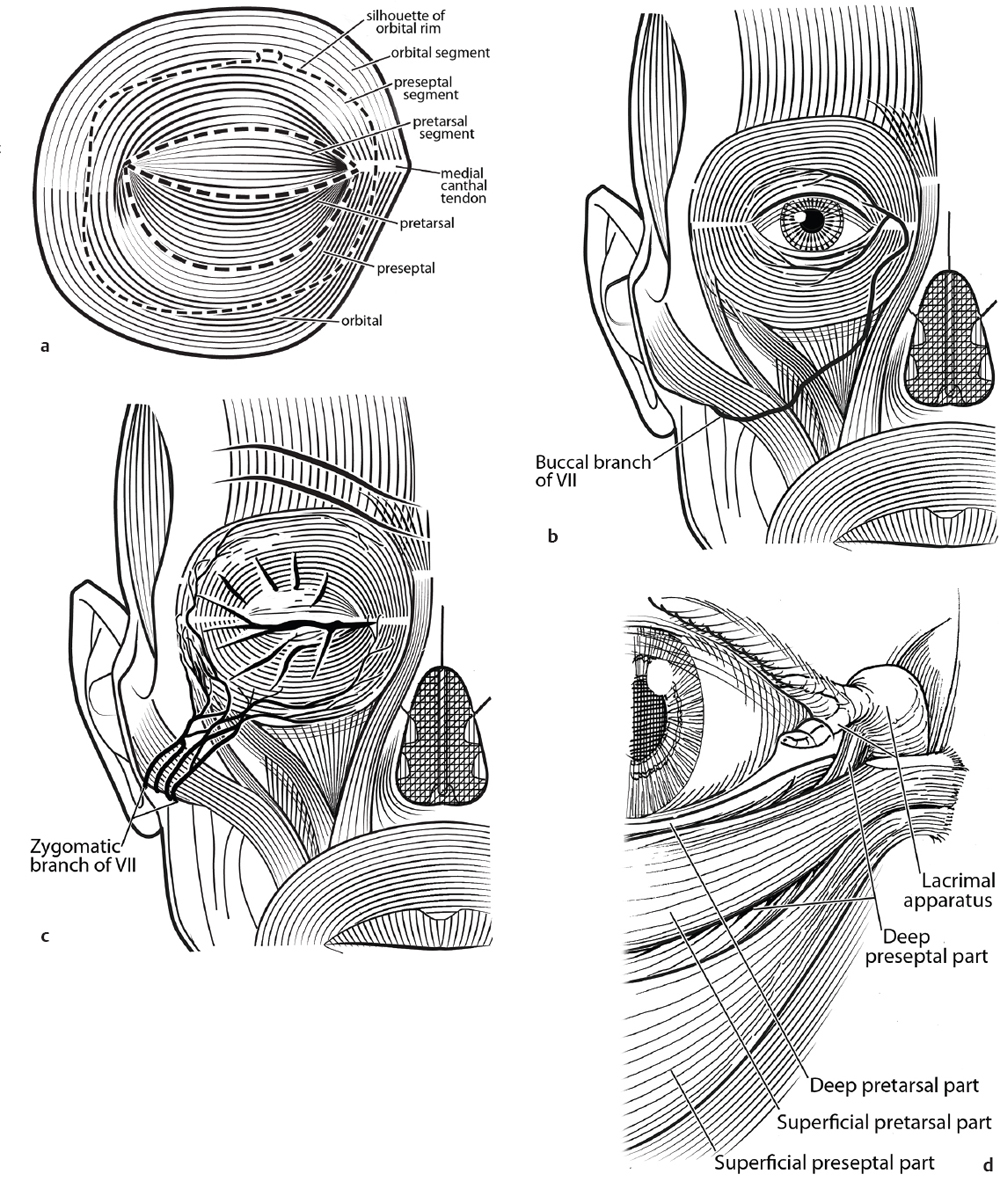

The orbicularis muscle serves two principal functional roles, for passive and purposeful eyelid closure and as a lacrimal pump that facilitates the progress of tears from the lacrimal gland, across the globe, out the lid punctum, and through the tear ducts into the lacrimal sac and nasal cavity. To further understand the orbicularis function, it can be divided based on anatomical location in two ways: (1) a concentric model, labeling the pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital orbicularis based on the underlying anatomy; and (2) an innervation-based model, based on the zygomatic branches of the facial nerve that innervate the extracanthal orbicularis and the buccal branches that innervate the inner-canthal orbicularis. This division in innervation (and, to a lesser degree, the division based on the concentric model of labeling) is reflected in a division of labor within the orbicularis. The extracanthal orbicularis (innervated diffusely by the zygomatic branches of the facial nerve) is responsible for purposeful and forceful eyelid closure (i.e., hard squinting in direct sunlight), whereas the inner-canthal orbicularis is responsible for minuteto-minute reflexive blinking that maintains the tear film and activates the lacrimal pump ( Fig. 26.2a–d ). Injury (surgical or otherwise) to the former mechanism has minimal functional impact; injury to the latter mechanism can have severely detrimental functional consequences.

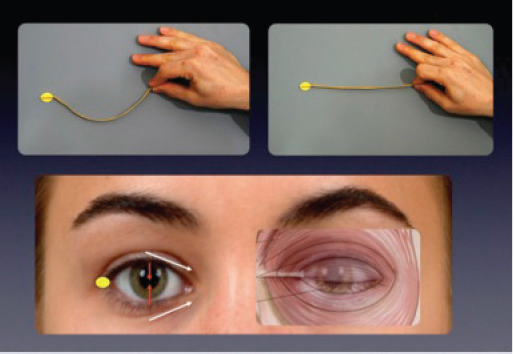

For the lid to function properly in closure, three aspects must work together: a stimulus (the nerve), a motor (the muscle), and an anchoring mechanism (the canthal apparatus). The canthal apparatus is made up of the medial and lateral canthus (with direct bony attachments based on the canthal tendons) and the tarsoligamentous sling that spans between them. When stimulated, the orbicularis muscle contracts in a horizontal fashion. However, the lid must traverse vertically across the convexity of the globe. The translation of a horizontal force into vertical movement of the eyelids is dependent on a stable and fixed medial and lateral canthus ( Fig. 26.3 ), without which complete eyelid closure cannot be achieved, resulting in fish-mouth lid closure and beady-eye syndrome ( Fig. 26.4 ).

Patient Selection

One of the most critical means by which to avoid complications from lower eyelid surgery is proper preoperative patient evaluation. This starts with taking a history that documents previous lid surgery, use of corrective lenses, previous refractive corneal surgery, and a history of dry eye. A history of dry eye requiring use of eye lubricants is an indication for preoperative punctal plugs to avoid severe dry eye postoperatively. Corneal refractive surgery temporarily renders the cornea insensate, inhibiting its protective mechanism. Thus, cosmetic eyelid surgery should be delayed for at least 6 months to minimize the risk of the corneal injury.

The physical exam includes an assessment of the Bell phenomenon, lid laxity, globe prominence, visual acuity, and midface vector. The Bell phenomenon, which is the upward tilt of the globe during lid closure, is intact in ~ 80% of the population. This response is corneoprotective, and when it is not intact, the cornea is put at higher risk for exposure during the early postoperative recovery period when the eyelids can be stiff and prone to lagophthalmos and poor closure. Visual acuity can be easily assessed before surgery. When documented, it can be readily referenced in case any changes in visual acuity occur after surgery.

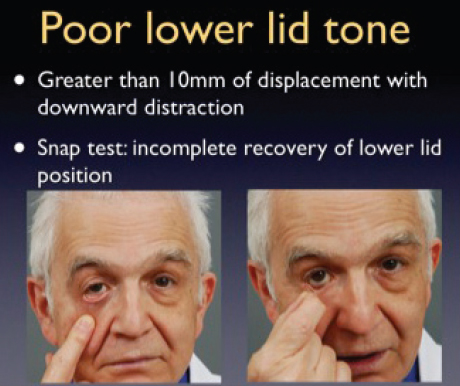

Most critical to avoiding lower lid complications are four clinical aspects: lower lid tone, globe position, midface vector, and prior lid surgery. Recognizing poor lower lid tone preoperatively and addressing it formally intraoperatively are key to avoiding lower lid malposition and ectropion. Scleral show (lid position below the level of the corneoscleral limbus) at baseline and distraction of the lower lid beyond 10 mm from the globe are de facto evidence of poor lower lid tone.

Another method to assess lower lid tone is the snap test. Normally, when the lower lid is distracted from the globe, it will snap back to baseline position on its own. In the patient with poor lower lid tone, the lid will not snap back on its own and will only take up a baseline position after an active blink ( Fig. 26.5 ).

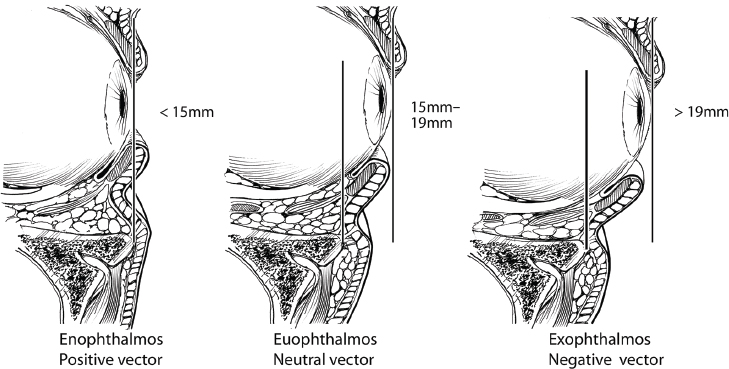

Globe position also affects lid position. A Hertel exophthalmometer can be used to measure the relative position of the globe to the bony orbit. Normal (euophthalmos) is 15 to 19 mm, enophthalmos is less than 15 mm, and exophthalmus is 20 mm or greater. The exophthalmic patient presents certain challenges to proper lid positioning and often requires special attention during lid surgery. Tightening the lower lid in a prominent-eye patient can easily lead to a clothesline effect of the lid position relative to the globe and result in lid malposition ( Fig. 26.6 ). The negative vector midface presents a similar challenge. Sometimes referred to as a polar bear midface, a heavy midface with a lack of midfacial skeletal prominence creates a negative vector slope and extra pull and downward drag on the lower lid.

Lastly, a history of previous eyelid procedures places the patient at significantly higher risk for postoperative complications. The presence of scar tissue, previous skin resection, skin resurfacing of the eyelid, prior canthal procedures, and even fat or filler injections, can all conspire to make lid surgery more technically challenging and increase the risks of lid position and functional complications. Typically, secondary lid procedures should be performed more conservatively and with specific planning to address preexisting or intraoperative lid findings. Identifying these four clinical aspects and designing an operative plan to address them goes a very long way to minimizing lower lid complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree