24 Complementary Fat Grafting

Introduction

The role of volume restoration has become increasingly recognized as an important if not primary mechanism by which the aging process occurs. There is renewed interest in facial fat grafting in the community of aesthetic surgeons owing to recent advances in technique that have proven beneficial in achieving consistently excellent cosmetic results while at the same time limiting morbidity and extending longevity. A simplified analogy can be used to understand the aging process in light of the primacy given to volume depletion: the face is like a grape in youth that over time becomes a raisin. The question then stands is why should the perceived redundant skin that arises be lifted, pulled, and cut away so that what is left no longer resembles the grape of youth but more like a truncated pea. Instead, we should fill the depressed facial zones as needed to achieve the highlights, contours, and convexities that define youth. This reductionist philosophy espoused here does not truly reflect the authors’ opinion entirely, as we recognize the complexity of the aging process that can be comprised of volume loss, volume gain, gravitational descent, and dermatologic changes. Nevertheless, what may have been perceived in the past as only gravity or skin redundancy should be reinterpreted as possibly arising from tissue deflation that could be corrected with facial fat grafting.

How then should we determine the best course of action for a prospective patient seeking to restore a youthful countenance? The best answer lies in old photographs of patients from when they were in their twenties. Assuming they looked young in these photos, the pictures can provide a blueprint in deciding which rejuvenative option(s) would be ideal for each individual. During the consultation and evaluation it is important that we do not merely focus on a specific complaint, such as having heavy eyelids, but instead have a big picture approach to rejuvenation. Using the example of the upper eyelid, if we have the patient step back and explain what they really want, it is to see a more youthful eyelid. We then must help our patients understand what is the package of characteristics that will re-create a youthful eyelid, and not one that had plastic surgery. In the case of the upper eyelid, traditional reliance on browlifts and blepharoplasty result in an unnatural elevation of the brow and skeletonization of the superior orbital rim. Inarguably this reduces the excess skin patients may complain of but does not create a truly rejuvenated eyelid, resembling their once youthful appearance. The old photographs provide a framework for our goals and help the patient understand what combination of procedures will provide a natural and rejuvenated appearance—be it fat grafting, microliposuction/liposuction, blepharoplasty, facelifting, and/or skin therapies. We have entitled this combination approach toward fat grafting complementary fat grafting, as we see the value in fat grafting not necessarily as a standalone procedure in every case but as a complement to traditional procedures ( Fig. 24.1 ). 1

This integrated strategy allows the surgeon to select the right combination of procedures that can be tailored to an individual based precisely on how that person used to look. Obviously, if the person did not like his or her appearance in youth, techniques can be modified to achieve the desired outcome based on mutual objectives established between the surgeon and prospective patient.

The advent of disposable microcannulas for use with officebased facial fillers, and the continued development of filler products intended for facial volumization, has challenged fat grafting as the sole method for facial volumization. Today, fillers may be considered a suitable alternative in many patients who desire fat transfer or as an adjunct to fat transfer because microcannulas can be used for advanced facial sculpting that fat grafting alone was only able to achieve a few years ago. This chapter will not delve into how to use fillers but instead on how individuals can be guided to determine whether a fat transfer, fillers, or some combination of both would be advisable based on multiple factors. As with everything in cosmetic surgery, preoperative education and counseling is the key and is emphasized here.

History

Fat grafting has assumed an increasingly prominent position in the armamentarium of the facial plastic surgeon over the past decade, as evidenced by the number of lectures dedicated to the subject at major conferences during that time. The roots of fat grafting, however, date back over a century ago with the first clinical case traced to Neuber in 1893 who described the use of fat grafting to restore a facial defect that arose from tuberculous osteitis. 2 Two years later, Czerny discussed reconstruction of a breast defect left behind by removal of a benign mass by implanting an excised lipoma. 3 In 1910 Lexer used larger parcels of transplanted fat to improve fat survival, 4 followed the next year by Bruning who restored a post-rhinoplasty defect successfully with fat grafting 5 and Tuffier who implanted fat into the extra-pleural space to ameliorate certain pulmonary conditions. 6 In 1932 Straatsma and Peer closed a fistula following frontal sinus surgery using autologous adipose tissue. 7 Two years later, Cotton morselized and placed fat to improve various contour defects.

The advent of liposuction in 1974 stimulated the interest in employing the removed fat as grafting material. 8 In 1982, Bircoll described using liposuctioned fat to correct a host of contour problems. 9 Illouz, 10 Krulig, 11 and Newman 12 continued the trend in using aspirated fat to recontour the face and body during the 1980s. The two proponents that have substantially influenced the current resurgence in autologous fat transfer are Sydney R. Coleman of New York 13 and Roger Amar of France, 14 who have advocated using gentler hand (rather than machine) suction for fat harvesting, followed by centrifugation to purify the fat cells, and injection of only tiny parcels of fat using blunt cannulas. Placing only very small amounts (0.05 to 0.1 mL per pass of the cannula) is argued to facilitate a smoother result and at the same time to improve longterm transplant survival owing to the enriched blood supply that surrounds each microparcel of fat.

Preoperative Considerations

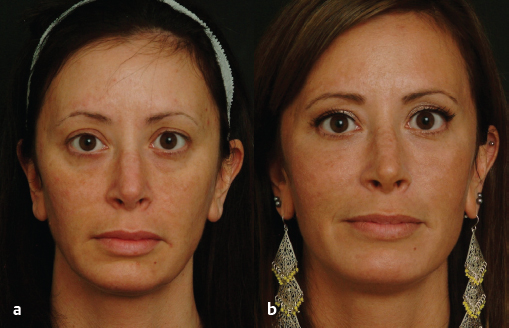

Explaining to a patient the potential benefits of fat grafting may initially be more difficult than convincing him or her of the merits of a facelift. Most plastic surgeons, the media, and one’s peers are familiar with what a facelift does, and most patients come through the door holding their face up with two fingers to indicate the desired changes. However, correcting the effects of gravity may not be the only beneficial course of action or may not be needed at all, especially in the younger individual. Oftentimes, a younger person in his or her thirties and early forties desiring facial rejuvenation may only exhibits signs of volume loss and would not benefit from a lifting procedure ( Fig. 24.2 ).

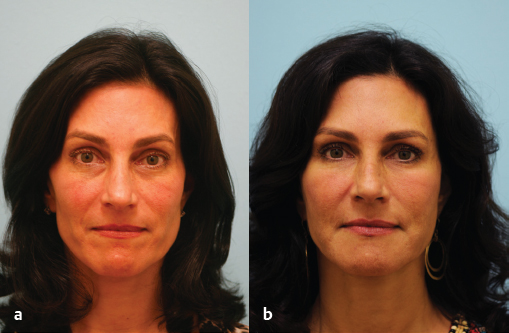

If one reflects for a moment how an observer can tell that another individual is a teenager, twenty-something, or thirtysomething even before acknowledging the influence of clothing styles or mannerisms, the answer lies in the volume changes of the face; more specifically, the ongoing loss of what is known colloquially as “baby fat.” In fact, some women and men would not like to go back to the exuberant fullness that characterizes a teenager or a twenty-something. Using old photographs can help establish dialogue about the evolution of aging that is witnessed in that particular individual and help establish appropriate goals for facial rejuvenation ( Fig. 24.3 ).

There are three key concepts useful for analysis of the volume-depleted face: facial volume and shape, highlights and shadows, and the importance of framing the eye. Each of these concepts is discussed below. As one matures, facial shape progresses from a youthful heart shape, or triangle, into a more squared off appearance. The apices of the youthful triangle are the malar prominences and the chin, all of which are full and convex. Over time, volume loss in the malar regions and mentum combine with volume contraction in the prejowl sulcus and soft tissue ptosis in the jowl to change facial shape. This narrowing in the upper face and widening of the lower face creates a more squared off shape typical of an older individual. One of the principle objectives in autologous fat transfer is to reconstitute the idealized triangle, or heart shape, that defines youth. The malar and chin region can be augmented with facial fat grafting, whereas the jowl can be reduced by selective microliposuction with or without a facelift as needed. In a patient with a heavy jowl and/or platysmal diastasis/neck descent, fat grafting alone will fail to achieve the desired aesthetic rejuvenation ( Fig. 24.4 ). In these cases, a combination approach with fat grafting to the malar and chin/prejowl areas (along with other deflated facial zones) together with a facelift will yield superior results.

The problem with oversimplifying the face into a triangle is that surgeons without an artistic eye will over augment these apices to create a distorted cheek- and chin-dominant face, something that has been seen to ill effect in the aging Hollywood starlets who exhibit the derisively albeit aptly named “pillow face.” The watershed zone that lies between the cheeks and the chin is the buccal area, which should be gently augmented to provide a more seamless transition between the two areas of augmentation in the right candidate. Similarly, too much emphasis has been placed in anterior projection, where aging can similarly affect the much-ignored outer face—the temple, the zygomatic arch, and below the bony arch. Accordingly, a revised paradigm for the ideal face of youth may be an oval shape, exhibiting aesthetically bright contour points and minimizing excess shadows and exposed bone ( Fig. 24.5 ).

The volume and shape of a face are what first give an impression of facial age and are the most important factors to control in achieving a youthful aesthetic result. Many women, in particular, evaluate their face using a magnifying mirror with bright illumination while applying their makeup. As a result they tend to focus on minor imperfections. However, most onlookers do not see these minor cutaneous flaws that the individual is complaining of, as they are often not visible to others at a normal conversational distance. To help patients appreciate this apparent contradiction it is useful to review current photographs of the patient, and if available look at photos of them at a younger age. In addition, showing examples of patients with similar facial aging changes, both before and after correction with fat transfer, is particularly enlightening for prospective patients. Review of these photos will help patients visualize the shadows that develop with aging which include the depressed brow, superior and inferior orbital rim, temple, anterior malar septum, submalar and buccal hollow, and prejowl sulcus/anterior chin. Demonstrating to the patient the dominance of facial shadows that develop with age will assist him or her in understanding the importance of eliminating senescent shadows and recreating youthful highlights with fat grafting. The important youthful highlights in the face include the lateral brow highlight, the anterior and lateral cheek highlights, and the chin highlights. Reducing the shadowed demarcations that divide the face and creating more youthful highlights can dramatically transform a tired, older face into a more vibrant, youthful one ( Fig. 24.6 ).

The third key concept in facial fat grafting concerns recreating an adequate frame for the eye. The eyes are perhaps the most important area to rejuvenate as they are the focal point of the face. Traditional blepharoplasty relies on the removal of skin and fat, and has a tendency to exacerbate an already hollow and aged eye—further depleting the youthful frame around the eye. In emphasizing volume we are not dismissing the role of skin excision, but feel that volume loss along the orbital rim and brow contribute to the development of skin redundancy and needs to be addressed with volume replacement. In practice this has translated into an approach to the upper lid where we perform a conservative skin excision with fat reduction, only when there is a significant medial fat prominence, in conjunction with fat transfer to the superior orbital rim. Addressing the lower lid involves transconjunctival blepharoplasty to conservatively reduce medial, central, or lateral fat, if they are prominent, combined with fat transfer to the inferior orbital rim and cheek ( Fig. 24.6 ). The cheek should be thought of as an extension of the lower eyelid subunit. An ideal youthful face will not have a demarcation between the lower lid and cheek, but will instead have a single convexity from lid to cheek. Creating the appropriate frame for the eye includes smoothly contouring the lid into the cheek.

Men typically like the increasingly sculpted appearance as facial volume loss occurs and generally present for correction at a later stage of volume loss. In contrast, women will often be more acutely aware and bothered by these changes at an earlier stage as the volume changes tend to masculinize the female face. Accordingly, facial fat grafting can truly feminize the face and restore the luster of feminine youth. The anterior cheek in particular when accentuated can be very feminizing. This is one of the areas where the goal of rejuvenation is gender specific, in that too much anterior cheek fullness will impart a feminine appearance to a man’s face.

Fat grafting has proven to be a beneficial rejuvenative tool across all racial divides. 15 Many individuals of darker complexion may be more recalcitrant to photodamage and gravity than the fairer-complected white race until a much later comparable age. Accordingly, facial fat grafting has been a principal mechanism for facial rejuvenation in all skin types, as every race suffers from volume loss in high measure. 16

As mentioned in the introduction, facial fillers have assumed an increasing role in their ability to mimic a fat-grafting result. Combined with the desire to avoid surgery, many patients are favoring this option. Although this chapter is not intended to discuss fillers in length, it is important that a surgeon be able to discuss the pros and cons of fat grafting and filler alternatives in a concise and deliberate manner during the preoperative setting.

Injectable fillers provide a quick and easy officebased alternative to fat transfer, with significantly less downtime and a shorter time until the changes are appreciated. The use of temporary fillers may be useful in patients who are not fully committed to the concept of volume rejuvenation, thus providing them with a “test result” before proceeding with fat transfer. Fillers may also be a less expensive option for patients who are younger and do not require much facial augmentation. In contrast, in patients with more advanced pan facial volume loss, fat is often a better option due to the high cost of large volumes of off-the-shelf filler and lack of a longterm result. In comparison to injectable fillers, fat is not as effective or reliable an option for treating more superficial lines and skin deficits. This is attributable to the fact that fat must be placed deeper, in a subcutaneous plane. It is important to emphasize to prospective patients that fat transfer is essentially a tissue graft requiring an adequate blood supply for optimal results; fat will not have 100% take and fillers may be necessary to optimize an aesthetic result. Like a hair transplant that gains blood supply over a period of a year, the result of a fat transfer will evolve over the first year. Therefore, it is usually recommended to wait close to a year postoperatively before deciding to proceed with secondary fat grafting. Finally, because fat is a live graft it may fluctuate with changes in a patient’s weight. An individual with a pattern of significant fluctuation of weight, or who is very young and may experience such changes, may be a better candidate for fillers to avoid issues related to volume change.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree