21 Transgender Breast Surgery

Summary

Many individuals with gender dysphoria seek surgical therapy to help alleviate their symptoms and allow them to become the persons they know themselves to be. Breast augmentation or mastectomy/chest reconstruction is often requested by transgender and gender-diverse individuals. While previously considered “cosmetic” in nature, these procedures have been shown to have significant therapeutic benefits and are often deemed medically necessary by patients, health care providers, and insurance companies. This chapter reviews indications, surgical techniques, and other considerations in providing care for transgender and gender-diverse individuals.

21.1 Introduction

Gender dysphoria is a condition where an individual’s assigned gender at birth causes significant distress or impairment. Many transgender and gender-diverse individuals who suffer from gender dysphoria seek surgical therapy to alleviate their symptoms. Breast or chest surgery, specifically either augmentation mammaplasty or mastectomy/chest reconstruction, are commonly requested procedures in the transgender and gender-diverse population. The overall goal of such procedures is to relieve or alleviate symptoms of gender dysphoria and allow individuals to live as the people they know themselves to be. Individual goals vary between patients. In some individuals, breast or chest surgery may be the only procedure requested, while in others, such surgery is one of many steps in their transition. From a technical perspective, the goals of surgery include a successful cosmetic and functional result with minimal complications. While breast and chest/reconstruction surgery were formerly considered “cosmetic,” they have increasingly been recognized as therapeutic and medically necessary procedures.

In caring for the transgender or gender-diverse individual, the surgeon functions as part of the multidisciplinary healthcare team. This team may include mental health professionals, primary care providers, and endocrinologists. As a team member, the operating surgeon should understand the diagnosis that has led to the recommendation for surgery; medical comorbidities that may impact the surgical outcome; the effects of hormonal therapy (when applicable) on the patient’s health; and factors that may predict the patient’s ultimate satisfaction with the surgical result. 1 Furthermore, the surgeon should help coordinate the patient’s postoperative care to ensure continuity.

Surgeons caring for transgender and gender-diverse individuals should be familiar with the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)’s Standards of Care (SOC). 2 These guidelines provide a flexible framework to help provide care to transgender and gender-diverse individuals. While procedures such as augmentation mammaplasty and chest surgery are not as invasive as genital surgery, the surgeon should take care in order to ensure that individuals pursuing such surgery are appropriate candidates.

The SOC recommend that individuals who request breast or chest surgery have one referral letter from a mental health provider. Mental health providers can come from a variety of disciplines (psychology, psychiatry, social work, nursing, family practice, etc.) and should have specific training and experience in caring for transgender and gender-diverse individuals. In addition to mental health evaluation, input from a patient’s primary care doctor or, in some cases, endocrinologist is useful in confirming that an individual is medically fit for surgery. The surgeon should, when needed, communicate directly with members of the healthcare team, especially if there are any questions regarding a patient’s appropriateness for surgery. The SOC recommend the following criterion for individuals who desire breast or chest surgery 2 :

Persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria.

Capacity to make a fully informed decision and to consent to treatment.

Age of majority in a given country (if younger, additional recommendations apply).

Reasonably good control of any significant medical or mental health concerns that may be present.

Hormone therapy is not a prerequisite for mastectomy/chest reconstruction surgery or augmentation mammaplasty. However, some insurance plans may require hormone therapy to preauthorize surgery. In the authors’ experience, it is uncommon for individuals requesting augmentation mammaplasty to achieve sufficient breast growth with hormonal therapy alone. However, 12 months of feminizing hormone therapy prior to augmentation mammaplasty may help to maximize breast growth and achieve a more stable result following surgery.

In appropriate surgical candidates, an in-person consultation should be obtained. During the consultation, the surgeon should discuss the surgical techniques, the advantages and disadvantages of the techniques, the limitations of the procedure, and the risks and possible complications of the various techniques. 2 Furthermore, the surgeon should discuss the individual’s expectations from surgery and review the postoperative care. Patients who have unrealistic expectations are at risk for disappointment with their final results.

If an individual decides to proceed with surgery, written documentation of informed consent should be included in the patient’s chart.

21.2 Augmentation Mammaplasty in Trans Women

21.2.1 Breast Development and Hormone Therapy

Breast development in prenatal life is independent of sex hormones and is, therefore, the same in males and females. 3 During embryonic development, breast buds composed of networks of tubules develop from the ectoderm. In females, these tubules will eventually become mature milk ducts. Until puberty, the tubule networks of the breast buds remain quiet. At puberty, male and female breast development diverges. In females, estrogen and progestins, in conjunction with growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), result in growth and maturation of the tubules into the ductal system of the breasts. Estrogens are generally believed to induce breast proliferation, whereas progestins result in differentiation. 4 Progestins are not thought to have a significant role in breast volume. 5 In contrast, in puberty of males, androgens (testosterone and dihydrotestosterone) increase about 10-fold higher compared to females, and estrogen is about 10-fold lower compared to females. The high levels of androgens strongly inhibit the action of estrogen in the breast at puberty, resulting in lack of breast development in men.

In trans women, some breast growth occurs with suppression of androgens and supplementation with estrogens. Androgen blockade can be achieved with antiandrogens. In the United States, spironolactone is the most commonly used antiandrogen, whereas in Europe, cytoproterone acetate is extensively used. One major difference between the agents is that cytoproterone also has progestogenic properties in addition to its antiandrogenic effects. Cytoproterone is not approved for use in the United States due to concerns of hepatotoxicity. Some centers use gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs to suppress androgen production, but cost limits use of these agents. Alternatively, orchiectomy is an effective way to reduce androgen levels.

Breast size typically begins to increase 2–3 months after the start of hormone therapy. Initially, breast buds begin to form and breast growth progresses over 2 years. 4 , 6 Because growth takes place over a period of time, the SOC recommend hormone therapy for at least 1 year prior to breast augmentation. 2 However, response to hormone therapy varies among individuals, and breast and nipple development in transwomen is rarely as complete as it is in cis women. Additionally, in some individuals, hormone therapy results in primarily subareolar breast hypertrophy with scant breast development elsewhere in the breast. As such, it is not uncommon for breast augmentation to be undertaken prior to 1 year of hormone use.

Few studies have addressed the optimal hormone regimen to maximize breast growth in transwomen. While studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of various hormone therapies, reported data are observational and subjective. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 The majority of available literature does not suggest that estrogen type or dose affects final breast size in transwomen. 4 In addition, current data do not provide evidence that progestins enhance breast growth. 4 Some authors suggest that younger age, tissue sensitivity, and body weight may impact breast size. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Furthermore, shoulder width may play a role in perceived breast size and adequacy of growth. 16 Overall, literature suggests that 60–70% of transwomen seek surgical breast augmentation because final breast size with hormone therapy is unsatisfactory. 4

Patients should be counseled on the degree of breast growth they may expect from hormone therapy and appropriate options should they desire larger breasts. Unfortunately, some trans women have resorted to “pumping,” an illegal and dangerous practice of injecting liquid silicone into breast tissue to enhance breast size. Serious complications of pumping range from local inflammatory reactions to pulmonary embolism and death. 17 Still, because it is an inexpensive alternative compared to approved treatments, the potentially deadly practice continues. 18

21.2.2 Augmentation Mammaplasty

Many trans women who experience inadequate breast growth with hormone therapy continue to wear external prostheses or padded bras. As such, augmentation mammaplasty may be requested. Breast augmentation can be performed at the same time as vaginoplasty; this can help decrease surgery time and cost in individuals who desire both procedures. In a retrospective survey of 107 trans women, Kanhai et al reported that 80% of participants had mammaplasty and vaginoplasty simultaneously. 19 However, all patients in this series underwent vaginoplasty. The percent of patients undergoing both procedures at the same time is likely far lower and varies between clinical practices. In some regions, shortages of trained surgeons and limited third-party coverage may reduce access to vaginoplasty procedures.

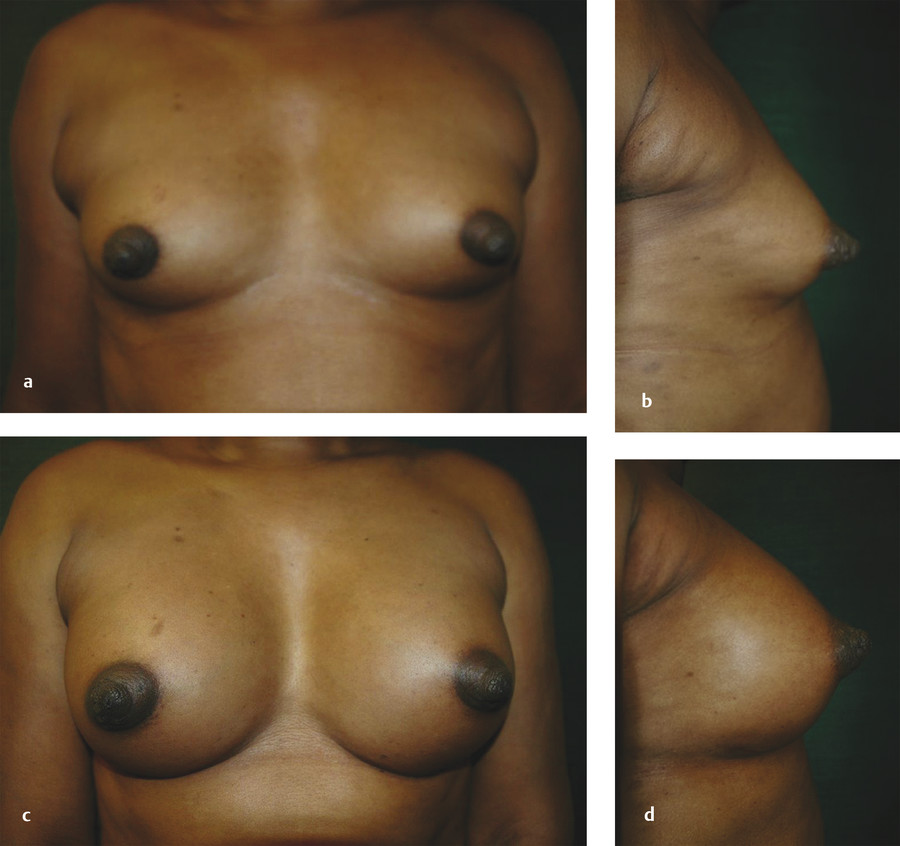

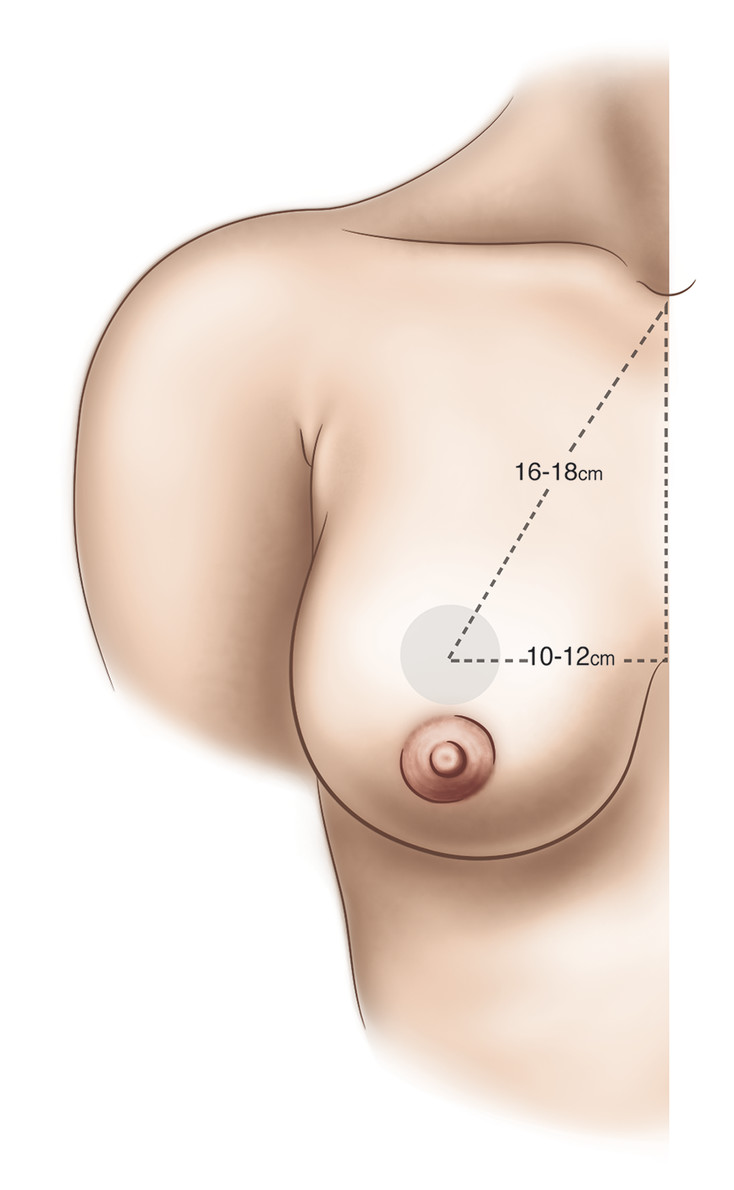

Anatomic differences between the male and female chest are relevant as to implant selection, incision choice, and pocket location. 20 The chest and sternum of cis men are not only wider than the chest of cis women, but the pectoralis major muscle is usually more robust. Furthermore, the areola of cis men is both smaller and more lateral compared to the areola of cis women. In general, in trans women, the skin envelope is tighter (particularly below the nipple areola), the distance between the nipple and inframammary fold (IMF) is less, and there is less breast ptosis (Fig. 21‑1). 21

Anatomic characteristics may require lowering the IMF by release of the sternal attachments along the rib and release of the lower sternal attachments of the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 21‑2). In releasing the sternal attachments of the pectoralis muscle, the overlying pectoralis fascia is left intact. These maneuvers may assist with implant positioning relative to the position of the nipple areolar complex (NAC) and also help to prevent lateral implant displacement. Due to the wider chest wall diameter and, consequently, wider inter-nipple distance in trans women, a wide inter-breast width is common, even with the selection of larger implants.

The implants may be placed in either a subglandular or a subpectoral pocket. This decision depends on clinical characteristics, including the degree of breast growth in response to hormonal therapy. Subglandular implants may be more palpable and may have higher rates of capsular contracture due to less soft tissue coverage overlying the implant, although opinions vary about whether submuscular placement reduces capsular contracture. However, subpectoral implants may be more prone to displacement and animation deformities due to the activity of the overlying pectoralis major muscle. The subpectoral position is preferred for thin individuals, while the subglandular position may be chosen for bodybuilders. Overall, the subpectoral position remains the most common pocket location, but the subglandular position may be appropriate for obese individuals or individuals with adequate soft tissue coverage.

In terms of incisions, transaxillary, periareolar, or IMF approaches may be used. The choice of incision is tailored to the requests and the anatomy of the individual. Due to the smaller size of the areola in trans women compared to cis women, and the use of larger implants, an IMF approach is most commonly chosen. Transaxillary incisions are sometimes used, whereas periareolar incisions are infrequently utilized. With the increased use of form-stable implants, larger incisions are often required, also favoring an IMF approach.

Implant selection is based upon patient preference and may also vary with surgeon preference. Most commonly, silicone implants (either round or form-stable) are utilized. Implant choice may be based upon base diameter, desired size, and nipple-to-IMF distance. The form-stable implants may assist with decreasing upper pole fullness, although long-term data is not yet available. With both devices, adjustment of the IMF may be required. Since the writing of this chapter, form stable implants are no longer used due to concerns associated with ALCL.

Selection of the final implant may be assisted with the use of intraoperative sizers. Additionally, secure fascial closure is important to maintain the position of the IMF.

Many trans women prefer larger implants. Kanhai et al reported that the average size of implants in trans women nearly doubled in their practice from 165 mL in 1979 to 287 mL in 1996. 20 In a long-term follow-up study of 107 patients, the authors reported that 25% of patients were unhappy with their mammaplasty. 19 A breast that was too small was the most common reason for dissatisfaction. Further augmentation was reported in 19% of these patients.

In order to decrease the risk of venous thromboembolism, hormones are discontinued 2 weeks prior to surgery, and either fractionated or unfractionated heparin is administered subcutaneously upon induction of anesthesia. Following surgery, a compression bra is worn for 3 weeks. The individual is also instructed to limit upper body exercise for the first several weeks following surgery, so as to decrease the risk of implant displacement. Gentle breast massage is instituted approximately 7–10 days following surgery.

21.2.3 Third-Party Payer Coverage

While there has been significant progress in third-party coverage for gender-confirming procedures, many, but not all, insurance providers continue to consider breast augmentation a “cosmetic” procedure. As such, they may deny insurance benefits. However, the SOC point out that in some individuals, a “cosmetic” procedure can have a radical and permanent effect on their quality of life. 2 In fact, research has suggested that gains in breast satisfaction, psychosocial well-being, and sexual well-being after breast augmentation in transgender individuals are statistically significant and clinically meaningful. 22 Because insurance benefits vary, benefits should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis to determine whether augmentation mammaplasty is covered.

21.3 Mastectomy/Chest Reconstruction in Trans men

21.3.1 Hormone Therapy

Although hormone therapy is not a prerequisite for mastectomy/chest reconstruction surgery in trans men, many individuals desire testosterone therapy for masculinization. Several formulations of testosterone are available, but it is most commonly administered intramuscularly or topically. Dosage should be titrated to reach plasma concentrations of an adult male. Testosterone binds to androgen receptors throughout the body and can suppress ovarian production of estrogen and progesterone. Because testosterone is converted peripherally to estradiol by the aromatase enzyme, estradiol will often remain measurable in trans men.

Testosterone therapy does not cause significant change in breast appearance aside from the growth of chest hair. However, on a microscopic level, some changes have been observed. Evaluation of surgically removed breast tissue from 100 trans men who had received testosterone therapy for at least 6 months showed decreased glandular tissue and increased fibrous connective tissue in 93% of the pathologic samples. 23 In addition, there was mild lobular atrophy and severe lobular atrophy in 86% and 7% of the tissues samples, respectively. Two fibroadenomas, 34 fibrocystic lesions, and no carcinomas were reported.

21.3.2 Breast Binding

Trans Men often use breast binding as a means to hide breast tissue. Breast binding involves using tight material to hold the breasts flat against the torso to hide them more easily beneath clothing. Little is known about the long-term health effects, if any, of breast binding. However, breast binding over several years can decrease skin elasticity and quality, and, as a result, can affect the surgical technique and aesthetic results from mastectomy and chest reconstruction.

21.3.3 Mastectomy/Chest Reconstruction

Chest-wall contouring is an important surgical step for many trans men. For some transgender and gender-diverse individuals, chest surgery is the only desired surgery while in others, chest surgery is one step in transitioning. The goals of chest surgery include the aesthetic contouring of the chest by removal of breast tissue and excess skin, reduction and repositioning of the NAC when necessary, release of the IMF when necessary, liposuction of the chest, and, when possible, minimization of chest scars and preservation of nipple sensitivity. 24

Before chest surgery is performed, preoperative breast imaging (mammogram or ultrasound) may be considered depending upon patient age, personal and family history, and physical examination. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends annual mammograms beginning at age 40. Earlier and additional testing may be warranted in high-risk individuals.

Chest surgery in trans men may present an aesthetic challenge due to breast volume, breast ptosis, NAC size and position, degree of skin excess, and potential loss of skin elasticity. In addition, concomitant obesity can increase the difficulty of achieving satisfactory contour, particularly in the subaxillary region. Breast binding may necessitate significant amounts of skin removal. Several surgical methods are utilized, and the choice of technique depends upon the skin quality and elasticity, the degree of breast ptosis, and the position of the NAC. 24 In addition, preservation of subcutaneous fat on the mastectomy skin flaps, preservation of the pectoralis and serratus fascia, release of the IMF and sternal attachments, and contouring of the lateral chest wall are also important components of chest surgery and chest wall contouring.

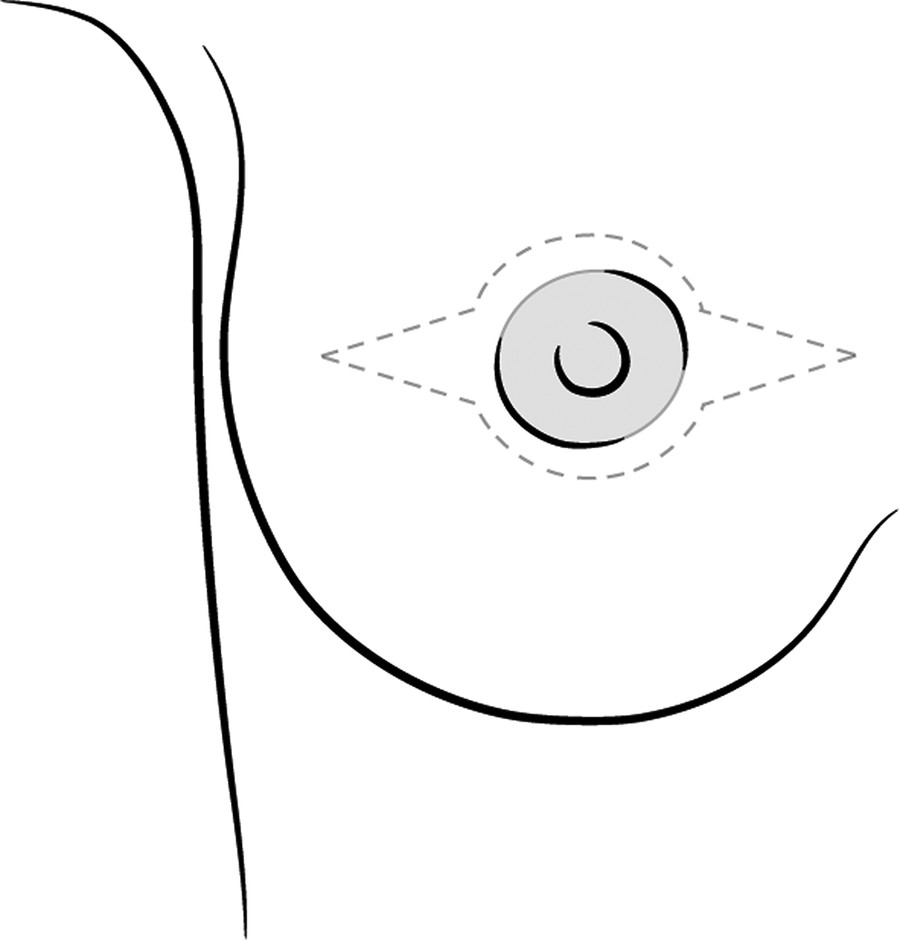

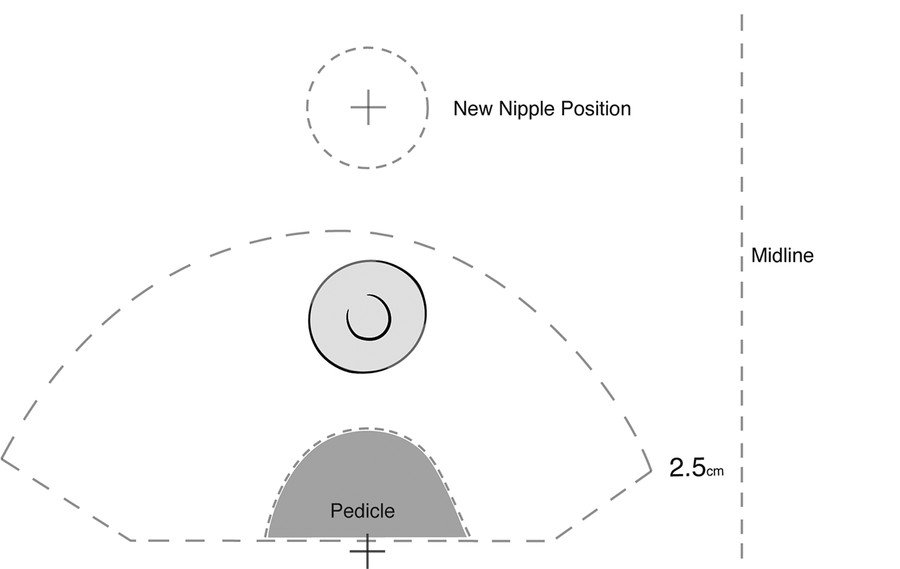

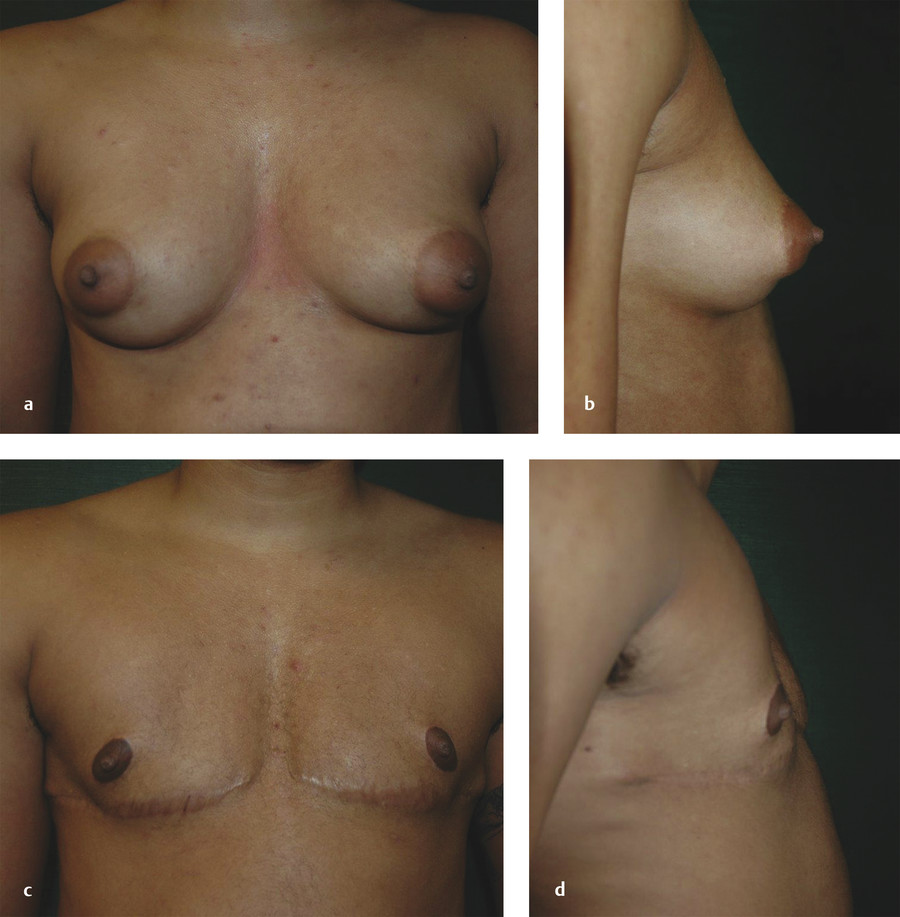

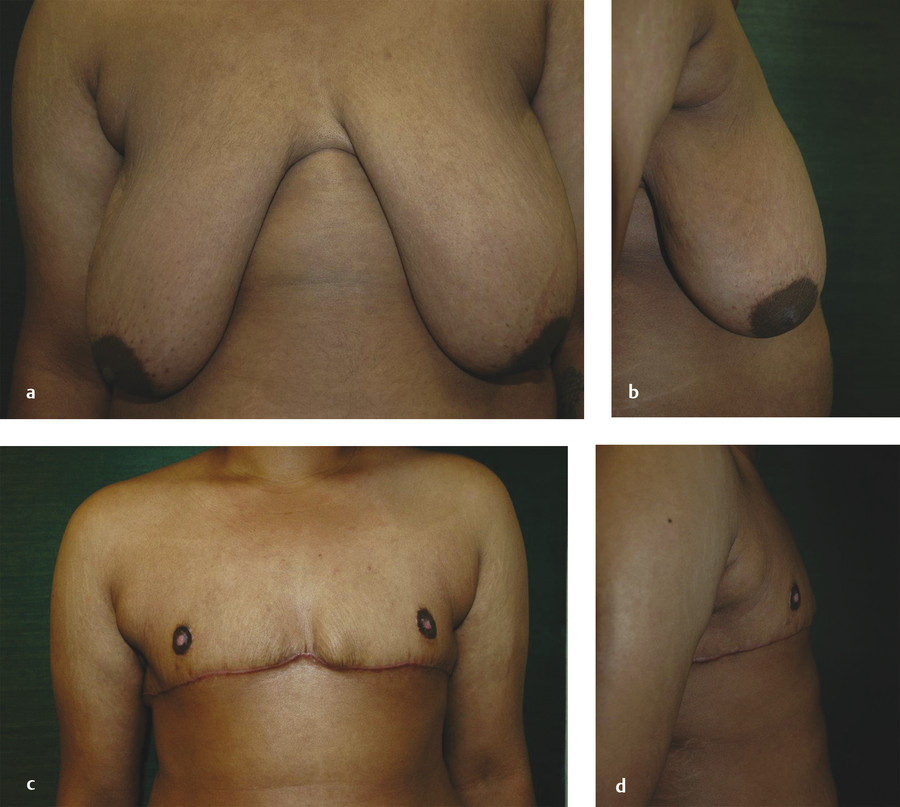

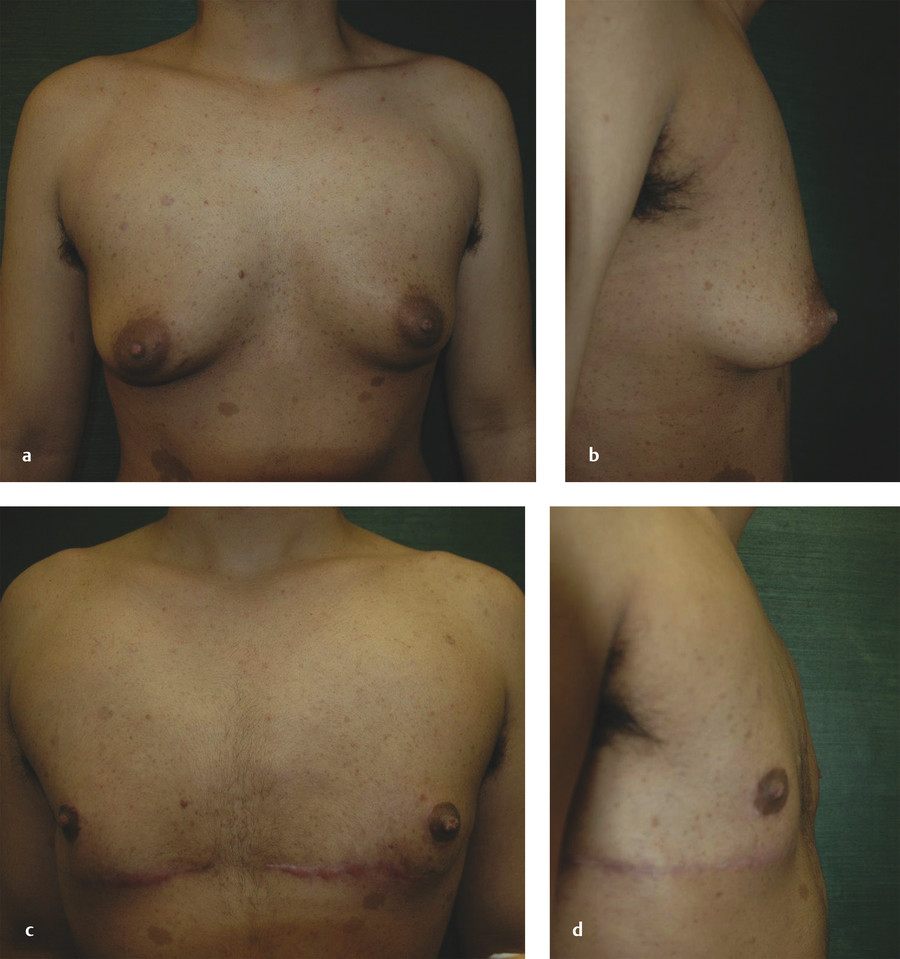

Small, nonptotic breasts can often be treated with periareolar incisions (“limited incision”). In these cases, the nipple may be reduced by a wedge resection of the lower pole, but the areola is not repositioned. A small amount of tissue is left beneath the NAC to preserve viability (Fig. 21‑3). Circumareolar (“purse-string”) combined with vertical or horizontal incisions with free nipple-areola grafts can be used for larger breasts with mild ptosis requiring smaller amounts of skin removal. The vertical or horizontal extensions may assist with reducing postoperative areolar spread and distortion, but may result in a less aesthetically camoflouged scar as compared to the IMF (Fig. 21‑4). Finally, traditional transverse IMF incisions (“double incision”) with free nipple-areola grafts may better serve individuals with larger breast volumes and increased breast ptosis requiring large amounts of skin removal (Fig. 21‑5). This approach facilitates excision of redundant skin. It is not uncommon to extend the incision laterally, into the axilla. Some surgeons extend the medial aspect of the incision across the midline in order to reduce medial “dog-ear” (Fig. 21‑6). Although crossing the midline produces a less aesthetic scar, contour improvement and reduced discrepancy between upper and lower incision lengths may make this approach desirable. When free nipple graft (FNG) is chosen for thinner subjects, a small dermoglandular pedicle is added to achieve a natural-appearing fullness under the nipple areola (Fig. 21‑7; also depicted is the authors’ incision design for FNG).

Nipple reduction is commonly employed, often in conjunction with free nipple-areola grafts. FNGs necessitate thinning of the nipple to enable graft survival. In addition, liposuction is frequently used for both chest wall contouring and discontiguous undermining of the IMF and lateral chest wall. While free nipple-areola grafts are the most common technique for nipple transposition, some surgeons maintain the NAC on a dermoglandular pedicle. While this technique may preserve sensation to the NAC, it may also lead to residual breast fullness. Patients should understand that they may have fullness using this technique. This residual fullness may be reduced at a secondary surgical setting with direct excision or liposuction. The pedicle will be less noticeable in obese subjects, but these individuals usually have larger breasts and longer nipple-to-IMF distances. For some surgeons, the decision to utilize an FNG may be based upon the distance from the nipple to the IMF. When this distance exceeds 6–7 cm, an FNG may be preferable so as to prevent secondary contour deformities related to the bulk of the dermoglandular pedicle. 25

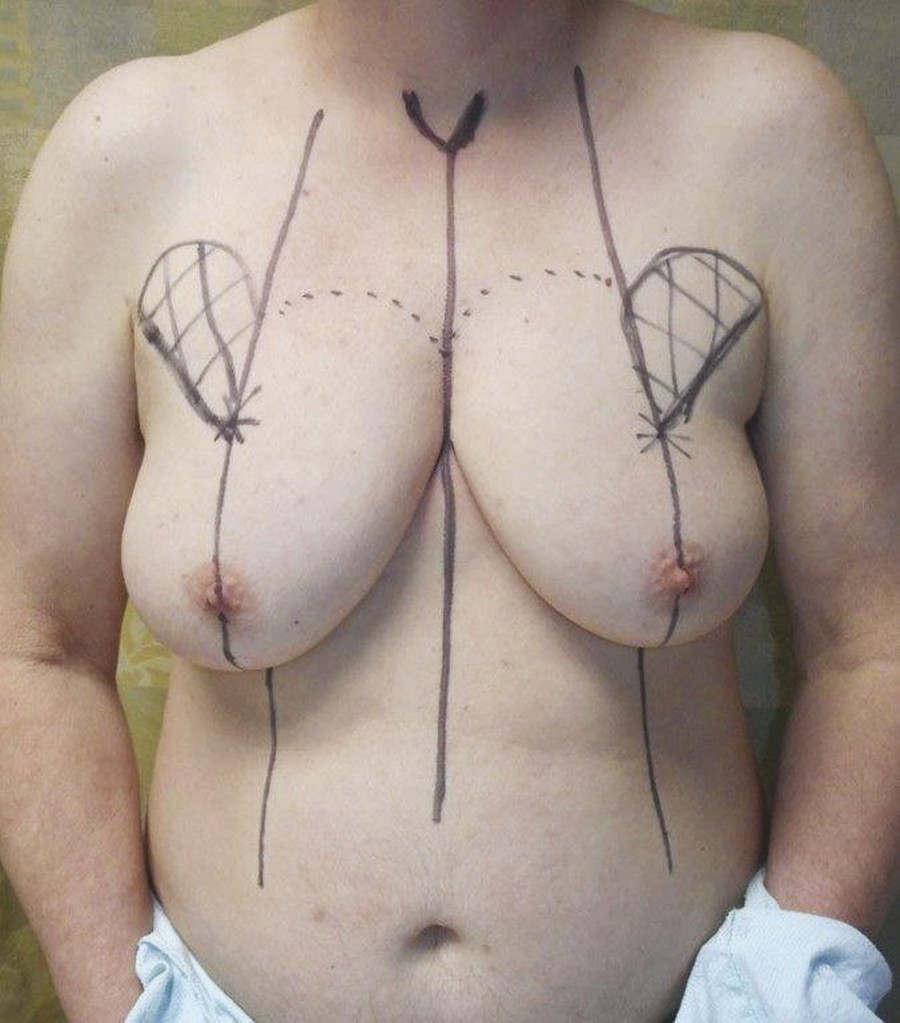

For patients on hormone therapy, testosterone is discontinued 2 weeks prior to surgery. The patient is marked in the upright position. The relevant reference points include the IMF, the midbreast meridian, the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle, the axillary tail of the breast, midline, and the anticipated position of the NAC (Fig. 21‑8). Alternatively, only the new nipple positions are marked standing and all other incisions are marked in a supine position after draping.

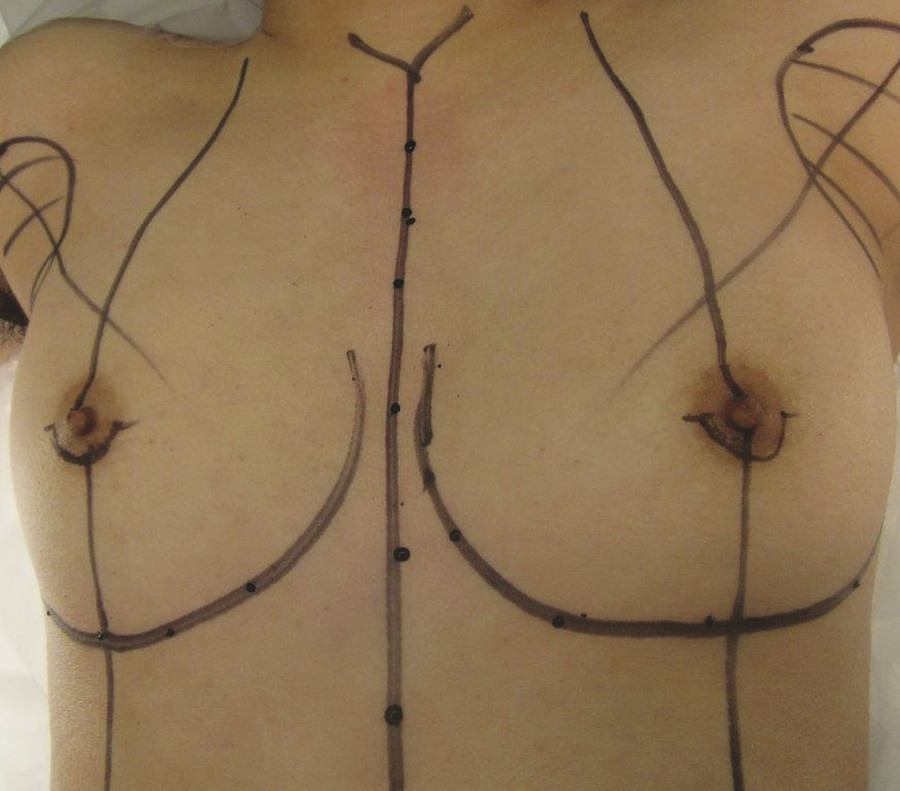

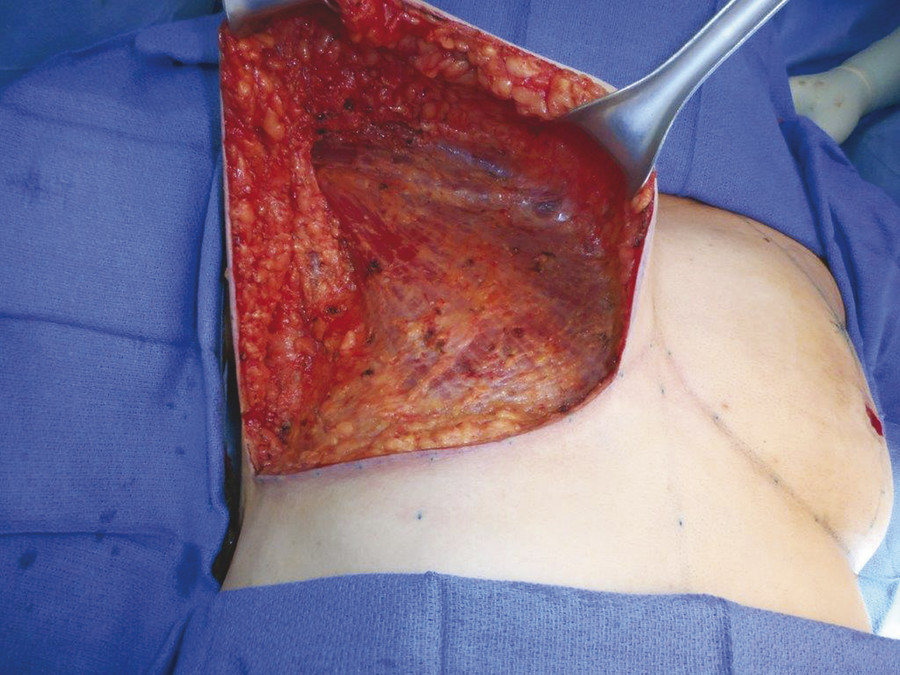

Prior to surgery, sequential compression devices are placed and intravenous antibiotics are administered. Following induction of general anesthesia, chemoprophylaxis for venous thromboembolism is administered subcutaneously (either fractionated or unfractionated heparin depending upon institutional policies). With each of the operative techniques, the patient is positioned supine, with the arms abducted on foam rests with flexion at the elbow, and a lower body forced-air warming blanket is placed. Draping should allow access to the surgical field from both above and below the upper extremity. In addition, the patient is positioned and secured in anticipation of flexing the back of the operating table in order to assess symmetry and guide placement of the nipple-areola grafts. The reference points are tattooed with methylene blue to aid with intraoperative identification (Fig. 21‑9). If free nipple-areola grafts are to be performed, the NAC is resized to a diameter of 2.5–3.0 cm. In addition, if a nipple reduction is required, a wedge resection of the lower pole of the nipple may be performed. The nipple-areola grafts are harvested, defatted, and placed in moist gauze sponges for later use. When a skin resection is planned, regardless of the technique, the anticipated area of skin resection is incised in order to facilitate breast removal. The skin flaps are developed at the junction between the breast tissue and the subcutaneous fat at the level of the breast capsule. The medial dissection of the breast stops at the sternal border, and the perforating branches of the internal mammary artery are preserved, if possible. The lateral dissection proceeds subcutaneously over the serratus muscle, with preservation of the serratus fascia, and the breast is reflected off the chest wall, with preservation of the pectoralis fascia (Fig. 21‑10). Liposuction of the IMF, the lateral chest, and the axillary tail is performed. Some surgeons place fibrin sealant in the cavity. The patient is placed in a semi-Fowler position, and the skin flaps are tailored and inset in a layered fashion over a 15 French closed suction drain. Following resection, the breast tissue is marked and sent to pathology for routine examination. Additionally, some surgeons choose to weigh the specimen intraoperatively.

There are no universally established guidelines for nipple position and areolar diameter in trans men. Some believe there is a tendency to create areolas that are too large and placed too high and medial on the chest wall. 26 , 27 Atiyeh et al proposed a mathematical formula for determining the ideal position for nipple placement in men after massive weight loss using the umbilicus–anterior axillary fold apex distance and the umbilicus–supersternal notch distance. 28 In addition, McGregor and Whallett reported on their technique for nipple-areola placement. 29 They suggest suturing threads at key points: the midclavicular position as the vertical axis, the midline axis of the sternum as the horizontal axis, and the suprasternal notch. The midline axis of the sternum is determined from a point on the upper arm midway between the elbow crease and the apex of the anterior axillary fold. The sutures are pulled along their axes. The point at which the sutures intersect is chosen for the nipple site. A 2-cm disk at this site is de-epithelialized for reception of the nipple-areolar graft. However, according to Monstrey et al, “absolute measurements can be misleading.” 24

In our experience, clinical judgment is best in positioning the NAC in trans men. In general, the nipple-areola is positioned medial to the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle, approximately 1–2 cm above the inferior insertion of the pectoralis major muscle. While specifics regarding nipple placement may vary, 26 , 30 placement falls within the parameters suggested in Fig. 21‑11. In obese individuals, the border of the pectoralis may be difficult to define. Final adjustments to nipple position may be performed at the time of wound closure.

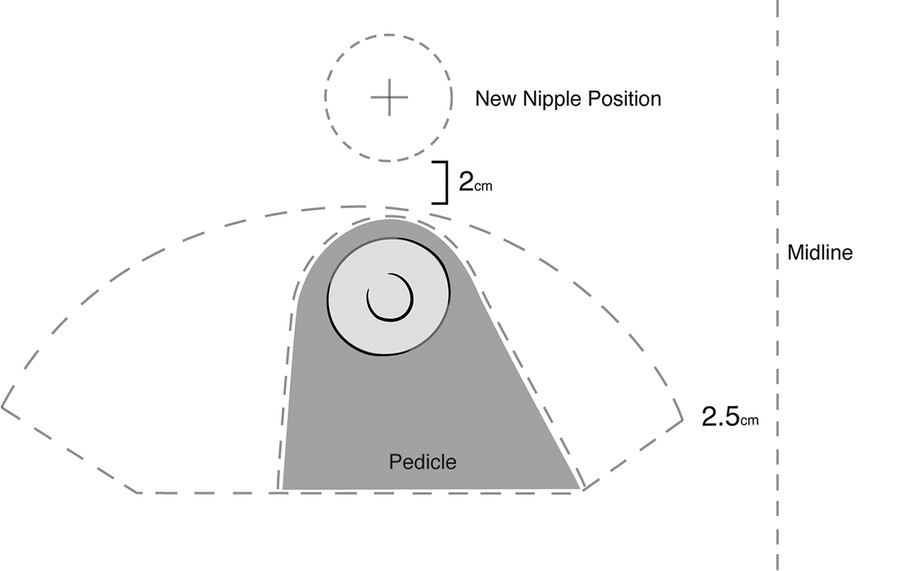

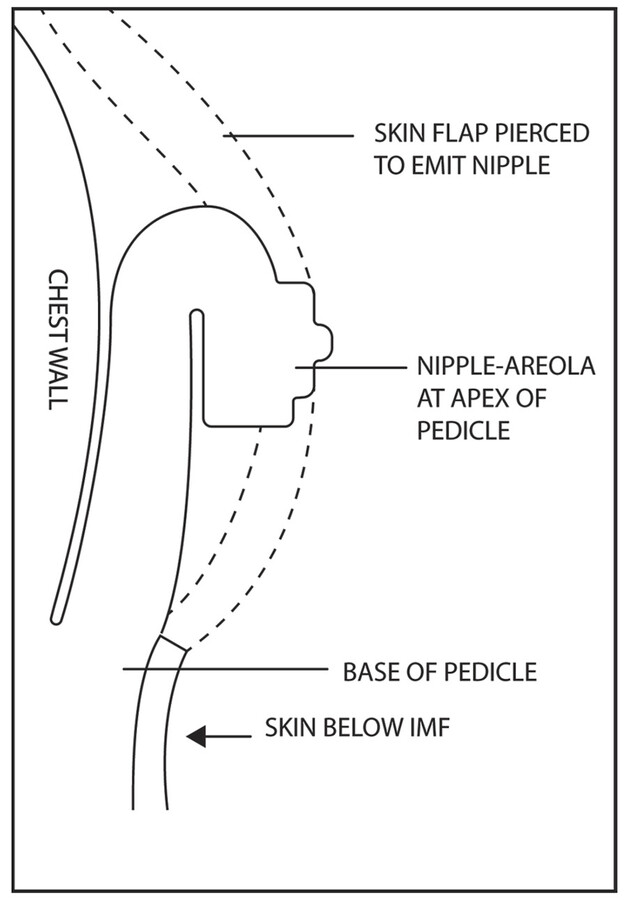

In general, markings are made in a standing position. For the double-incision approach, the authors’ preference is to place the lower chest incision at the IMF in order to remove breast tissue at this level. However, some surgeons place the lower chest incision at the lower border of the pectoralis muscle. If an inferior pedicle nipple transposition is planned, the areola is sized to 25 mm, and the pedicle is elevated deep to the level of the breast capsule. The pedicle is then de-epithelialized and can be sutured to the pectoralis fascia underlying the planned nipple position. The base of the pedicle is left in continuity with the underlying fascia (Fig. 21‑12). Alternatively, some authors describe disruption of the IMF so as to improve subsequent chest contour, but this maneuver may compromise the flap circulation. 31

Following development of the pedicle, the upper incision is made down to the level of the breast capsule. Dissection proceeds superiorly and medially to the pectoralis fascia and laterally to the fascia overlying the serratus anterior muscle.

Prior to wound closure, liposuction of the chest wall may be performed for additional contouring. This it typically performed in the lateral chest or subaxillary region and/or the lower chest/upper abdomen/midline region. Most often a closed-suction drain is placed, and some surgeons also use fibrin sealant.

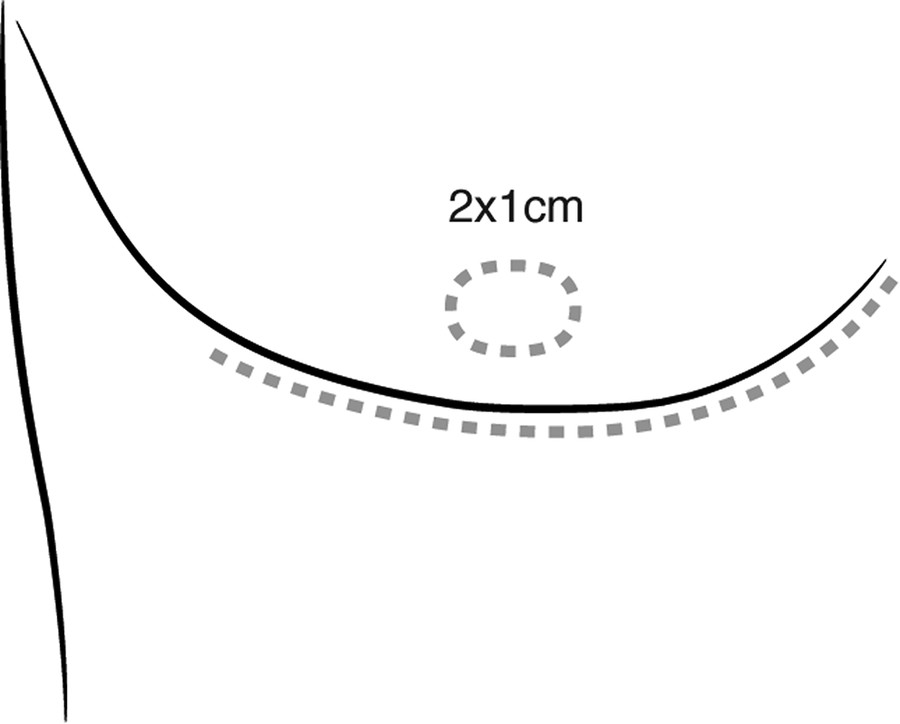

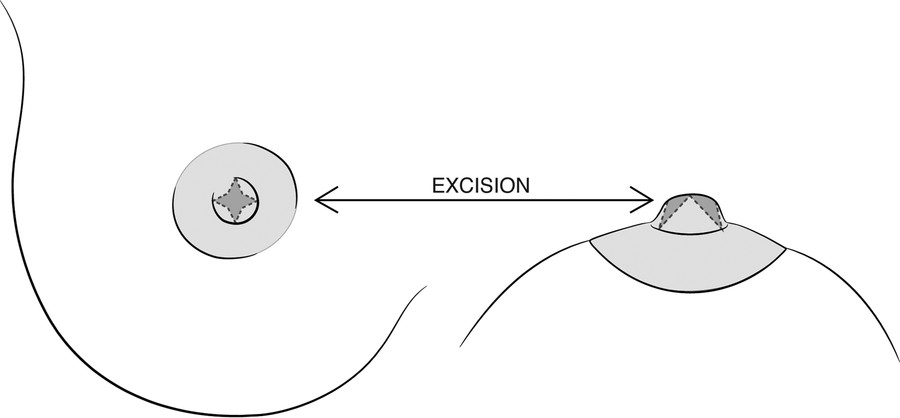

Final adjustments to nipple position are performed at the time of wound closure with the patient in a semi-Fowler position. The nipple position can be adjusted so that the inferior border of the areola is approximately 2–2.5 cm above the IMF and equal distance from the midline and sternal notch. These measurements may vary based upon common asymmetries in chest wall dimensions. When a pedicle technique is used, a 2 × 1–cm full-thickness ellipse of skin is excised in the chest flap (Fig. 21‑13). Due to flap tension, the ellipse becomes circular upon final inset. The nipple-areola is sutured with a single layer of interrupted, buried, absorbable sutures. In pedicle procedures, when a nipple reduction is required, it is performed at a secondary setting utilizing a three- or four-pointed star-shaped excision (Fig. 21‑14). When FNGs are used, the grafts are defatted and inset on a dermal bed. Fixation of the nipple graft is accomplished with a bolster dressing sutured over petrolatum gauze and an absorbant cotton pad. A compression wrap with elastic bandages is then placed.

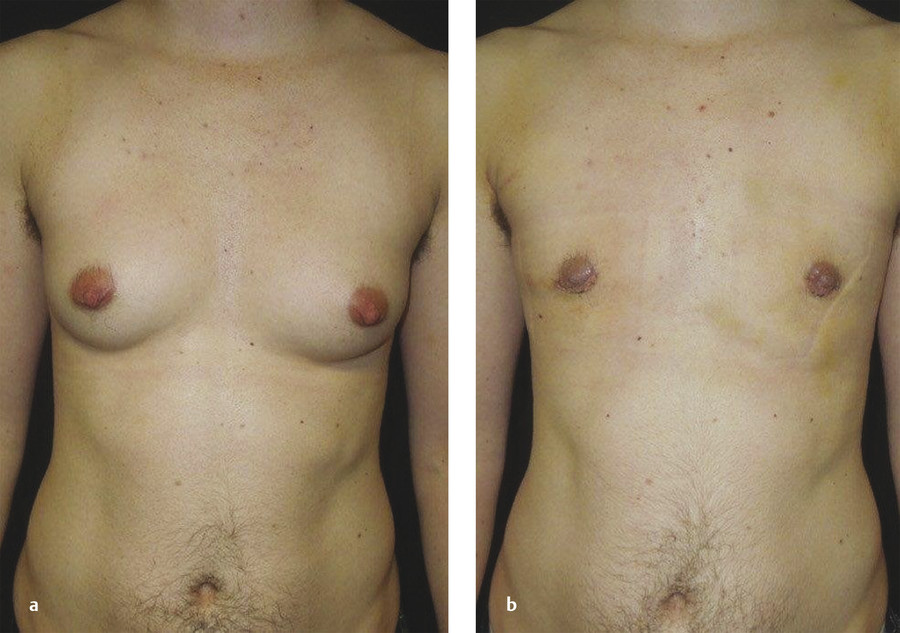

Examples of several chest surgeries are provided. Fig. 21‑15 shows a 27-year-old trans men before and 9 months after pedicle reduction. Fig. 21‑16 shows a 24-year-old trans men before and 6 months after chest surgery using the FNG technique. Finally, Fig. 21‑17 shows a 20-year-old trans men and 6 months post chest surgery using the inferior pedicle technique.

Chest surgery is generally performed as an outpatient procedure, unless the patient is traveling or has other medical comorbidities. Following surgery, an elastic compression wrap remains in place for 4–6 days. In addition, closed suction drains are placed bilaterally, and patients are instructed to monitor and record output. Discharge medications include an oral narcotic or non-narcotic alternative for analgesia, an antibiotic, a stool softener, and an antinausea medication. Patients are encouraged to ambulate as soon as possible. Patients can bathe, but not shower, until dressings are removed. Lifting is limited to 10–15 lb (4.5–6.8 kg) for several weeks, and patients sleep with their back elevated for 1 week after surgery. At an office visit 4–6 days after surgery, dressings are changed, bolster dressings are removed from the NACs, and local care with a topical antimicrobial ointment is initiated. The compression wrap is continued for 3 weeks after surgery, followed by a compression shirt for an additional 3 weeks. Drains are removed when output is less than approximately 30 mL per 24-hour period. It is recommended that patients stay locally for approximately 1 week after surgery before travel. For patients on hormone therapy, testosterone can be restarted a few days following surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree