Urticarial vasculitis usually follows a chronic or recurrent course, particularly in cases not attributed to a medication or infection. The spectrum of disease ranges from isolated cutaneous lesions to severe systemic involvement. Patients with hypocomplementaemia tend to have a higher incidence of systemic disease [2,15,18]. Associated clinical findings or systemic manifestations reported in patients with urticarial vasculitis are listed in Box 163.1. Angioedema of the face or hands is seen in up to 50% of patients. Arthralgias and arthritis are also common [2,15,18,26]. Chronic obstructive lung disease, seen predominantly in smokers, is one of the most serious or life-threatening complications in adults [17]. Restrictive lung disease with pulmonary haemorrhage has been reported in four children, three of whom were siblings [3,8]. Renal involvement in adults is usually benign, but can lead to end-stage renal failure [29,30]. Two of the five reported paediatric cases associated with glomerulonephritis progressed to end-stage renal disease despite therapy [8,13], but it is unclear if this is a reporting bias. There may be years between the onset of cutaneous lesions and overt glomerulonephritis, with the longest reported lag time of 10 years in a child [4,11,13].

Box 163.1 Associated Findings or Systemic Involvement Reported in Patients with Urticarial Vasculitis [2,3,8,15–18,26,29,30,56]

- Angioedema

- Arthralgias or arthritis*

- Fever, malaise or fatigue

- Abdominal pain

- Lymphadenopathy

- Photosensitivity

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Hyper- or hypothyroidism

- Pulmonary involvement

- Chronic obstructive lung disease

- Asthma

- Pleural effusion or pleuritis

- Pulmonary haemorrhage

- Renal involvement

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis

- Crescentic (rapidly progressive) glomerulonephritis

- Central nervous system involvement

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Pseudo-tumour cerebri

- Cranial nerve palsy

- Meningitis

- Ocular involvement

- Episcleritis

- Uveitis

- Conjunctivitis

- Cardiac involvement

- Pericardial effusion or pericarditis

- Valvular heart disease

* Rare reports of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis associated with Jaccoud arthropathy, a chronic deformity characterized by ulnar deviation of the second to fifth fingers and subluxation of the MCP joints; most cases also associated with cardiac valve disease [57–60].

Histopathology.

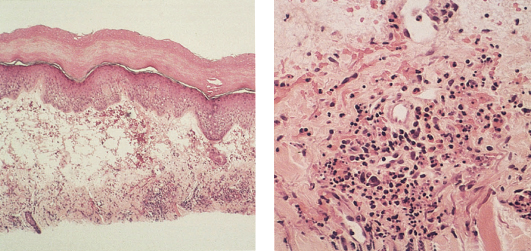

The hallmark histopathological features of urticarial vasculitis are those of a small vessel necrotizing (leucocytoclastic) vasculitis affecting the superficial vascular plexus, with endothelial cell swelling, leucocytoclasia (fragmentation of nuclei), erythrocyte extravasation, and fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls (Fig. 163.2). While evidence of vessel damage distinguishes urticarial vasculitis from urticaria, there is no consensus regarding the criteria required to make a histopathological diagnosis of vasculitis. Leucocytoclasis and fibrinoid deposits are usually considered the most direct signs of vessel injury, and many authors have suggested that the histopathology of urticarial vasculitis may show only sparse nuclear debris and fibrinoid deposits [1,31].

Fig. 163.2 (Left) Urticarial vasculitis with interstitial inflammatory infiltrate. (Right) Urticarial vasculitis with leucocytoclastic vasculitis.

Lee et al. reported a series of 22 patients with clinical features of urticarial vasculitis, only three of whom had a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate with frank evidence of leucocytoclastic vasculitis. The other patients in their study had a lymphocyte-predominant infiltrate, often with endothelial cell swelling and red blood cell extravasation, and variable numbers of eosinophils, which the authors suggested represented a ‘lymphocytic vasculitis’ [32]. Their inclusion criteria have been questioned [33], and many authors require at least subtle evidence of leucocytoclastic vasculitis to make a diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis. It should be noted, however, that leucocytoclastic vasculitis is initially a predominantly neutrophilic process that evolves into a lymphocytic process, and the age of the individual lesion sampled may affect the histopathological findings [24,25].

Biopsy specimens of urticarial vasculitis often reveal other features seen in urticaria including dermal oedema and an interstitial inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and/or lymphocytes. Eosinophils may also be a prominent finding. Patients with hypocomplementaemia are more likely to have a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate in the dermis [2,15,18]. Some authors have proposed that there is a spectrum of histopathological changes in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria, ranging from a sparse perivascular inflammatory infiltrate to a dense perivascular infiltrate to leucocytoclastic vasculitis (defined as leucocytoclasis and/or fibrinoid deposits in and around vessel walls), and there is not a clear histopathological distinction between urticaria and urticarial vasculitis [34,35].

Immunohistopathology.

Direct immunofluorescence from lesional skin may show IgG and/or C3 staining in a granular pattern along the dermoepidermal junction and around blood vessels. Positive direct immunofluorescence findings are more common in patients with hypocomplementaemia [2,15,16,18]. These findings are not specific for urticarial vasculitis.

Diagnosis.

In addition to a complete history and physical examination, work-up should include screening laboratory tests, as suggested in Box 163.2, to evaluate for an underlying cause or evidence of systemic disease. Complement levels, including C1q, C3, C4 and CH50, should be measured during active disease on at least two or three occasions. If there is concern about systemic involvement, additional tests should be considered such as chest X-ray, pulmonary function tests, bronchoalveolar lavage, slit-lamp ocular examination, joint and skeletal X-rays or echocardiography, with further testing based on symptoms and laboratory results [1,31].

Box 163.2 Laboratory Screening to Consider in A Patient with Urticarial Vasculitis

- Complete blood cell count

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- C-reactive protein

- Urinalysis

- Serum chemistry profile including serum urea and creatinine

- Liver function tests

- Serum complement levels, including C1q, C3, C4 and CH50

- Circulating immune complexes

- Serum immunoglobulins

- Cryoglobulins

- Anti-C1q antibody (C1q precipitin)

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

- Anti-DNA, SS-A(Ro), SS-B(La) antibodies

- Antiphospholipid antibodies

- C3 nephritic factor

- Hepatitis B and C serology

- Epstein–Barr virus serology and/or monospot test

- Lyme serology

Hypocomplementaemic Urticarial Vasculitis Syndrome

In 1973, McDuffie et al. described four women with urticarial skin lesions, arthritis, abdominal pain and hypocomplementaemia, two of whom had glomerulonephritis [36]. Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome is now the preferred term used to refer to patients with chronic urticarial vasculitis, anti-C1q antibodies and systemic involvement such as angioedema, pulmonary disease, glomerulonephritis and ocular inflammation. There is debate in the literature, but it is generally thought to be a rare autoimmune disease distinct from SLE [23,37], although there is significant overlap in clinical features and urticarial vasculitis has been reported in patients who meet criteria for SLE [15].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree