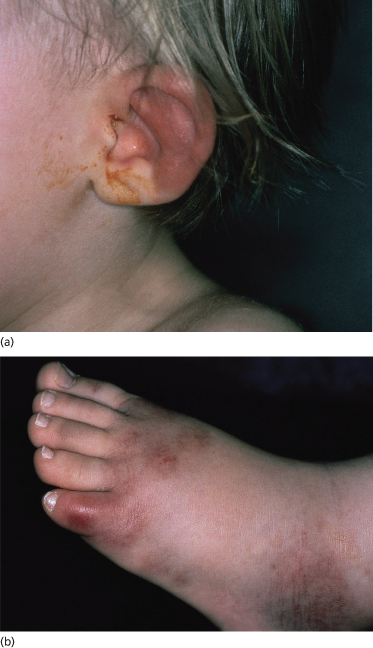

Fig. 161.2 AHO in a 12-month-old boy, featuring a typical cockade purpura on the face (a) and the legs (b).

Oedema resembling that seen in nephrotic syndrome may affect the eyelids or, more diffusely, the face. In one-half of the patients, swelling of the earlobes also occurs. The oedema can cause weight gain [8]. Other occasional cutaneous signs include petechial or reticulate purpura, necrotic lesions, mainly on the ears, and urticaria. The rarity of visceral involvement is one of the main characteristics of AHO. Although difficult to assess in infants, joint pain has been noted only exceptionally. Isolated cases of serosanguinous diarrhoea, of possible infectious origin, and melaena have been reported but, in contrast to HSP, vomiting and abdominal pain are not classic features. Kidney involvement with microscopic haematuria, mild proteinuria or increased blood urea nitrogen levels, when present, has always been transient [19,20].

A limited number of investigations have revealed the presence of serum immune complexes in some cases. Normal serum complement level has been detected; there is no isolated increase in serum IgA [1].

Some difficult-to-classify cases seem to suggest an occasional overlap between AHO and HSP. Those patients are older than 24 months and the purpura may be ecchymotic, reticulated or papular but lack the cockade pattern. Localized oedema can occur, along with extracutaneous symptoms, such as joint and abdominal pain. The duration of illness is longer [1].

Prognosis.

Spontaneous and complete resolution occurs within 1–3 weeks (mean 12 days), after one to three outbreaks of new lesions [1]. Long-term follow-up is not available in most cases, but the absence of reported complications [21] suggests that AHO runs a benign course. Intussusception followed by surgical complications and death was described in one case [22]. Torsion of the testis has also been reported in one child [19].

Differential Diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis includes: necrotic purpuras (especially purpura fulminans) [1], cockade eruptions (such as erythema multiforme), urticaria [23] and Kawasaki disease [24]. It should be stressed that all these disorders may include a non-pitting oedema of the extremities, which should be considered age specific rather than disease specific. Child abuse should also be considered (A. Taïeb, personal observation). A recent series mentioned eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome) as a possible differential diagnosis [9].

The relationship between AHO and HSP remains somewhat controversial. Table 161.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree