Chapter 33 Sagittal Band Injuries—Primary and Secondary Management

Outline

Subluxation or dislocation of the extensor tendon at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint is typically seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis but may also be seen with trauma, congenital laxity of the sagittal band, infection, and iatrogenic injury. Spontaneous sagittal band disruption has also been reported.1 A sagittal band injury will often present with pain and swelling near the MCP joint, with associated subluxation, or catching. The radial sagittal band is typically damaged, with resultant ulnar deviation of the involved finger. The long finger is most frequently involved. Treatment options are multiple and include splinting, realignment with direct repair, and various forms of tendon reconstruction.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

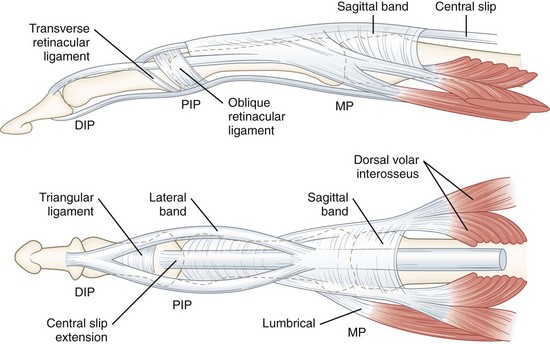

The sagittal band is one component of the extensor retinacular system, which forms a cylindrical tube with the palmar plate (Figures 33-1 and 33-2). This tube surrounds the metacarpal head and MCP joint.2 In the central digits, the origin of the sagittal band is palmar and blends with the palmar plate, flexor tendon sheath, proximal annular pulley, and deep transverse metacarpal ligaments (DTML). The sagittal bands on the radial side of the index finger and ulnar side of the small finger differ, in that they do not blend with the DTML. The insertion of the sagittal band is dorsal and tendinous, and glides with the extensor system as the digits move. The fibers superficial to the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendon are thinner than the deep fibers, especially in the central digits. The radial component of the sagittal band is typically thinner and longer than the ulnar component, explaining the predilection for radial-sided injury.

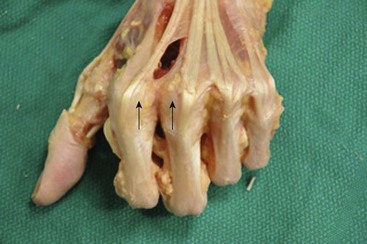

Figure 33-2 Cadaver dissection demonstrating sagittal bands (arrows) and surrounding extensor retinacular system.

The primary functions of the sagittal band are to help extend the proximal phalanx and to stabilize the extensor tendon in the midline over the dorsal aspect of the MCP joint.3 The force displacing the tendon in the ulnar direction is greatest in full extension, decreases from 0 to 60 degrees, and then increases again from 60° to 90° of flexion.4 Significantly higher forces are required to prevent additional displacement of an already ulnarly displaced tendon, and it tends to displace further with additional MCP flexion.

The long finger is most frequently involved5, likely because the tendon to the long finger sits on top of the transverse fibers with a relatively loose fibrous attachment, and the long finger extensor hood attaches more distally from the joint than that of the adjacent tendons.6 In addition, the cross-sectional shape of the extensor tendon of the long finger over the MP joint is rounder and less anchored than that of the other extensor tendons at that level.7 The injury is most often located on the radial side, with subsequent displacement of the extensor tendon in an ulnar direction.

Young and Rayan8 studied the anatomy and biomechanics of the sagittal band in 48 cadaveric digits and concluded the following: (1) extensor tendon instability following sagittal band disruption is most common in the long finger and least common in the small finger; (2) ulnar instability of the extensor tendon is due to partial or complete radial sagittal band disruption, (3) the degree of extensor tendon instability is determined by the extent of sagittal band disruption, (4) proximal rather than distal sagittal band compromise contributes to extensor tendon instability, (5) great forces are inflicted on the sagittal band while the MCP joint is in full extension or less frequently in full flexion, which may be the mechanism of its injury, and (6) wrist flexion contributes to extensor tendon instability after sagittal band disruption and may exacerbate the severity of its injury.

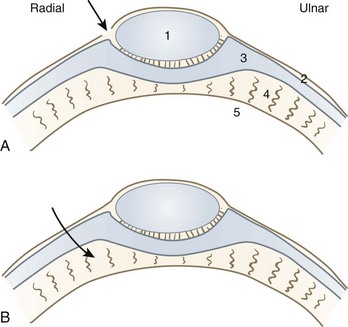

Ishizuki reported on differences in anatomical intraoperative findings, depending on if the injury was spontaneous or traumatic (Figure 33-3).1 Spontaneous dislocations involve rupture of the superficial layer of the sagittal band just radial to the extensor tendon, while traumatic dislocations rupture both layers of the sagittal band several millimeters radial to the extensor tendon.

Causes

The causes of sagittal band injuries are multiple, and include degenerative disease, trauma, congenital, infection, and iatrogenic injury.9,10 Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common cause of subluxation or dislocation of the extensor tendon at the MP joint. It is most frequently seen in advanced cases with ulnar deviation (Figure 33-4) but may also be seen in cases without severe deformity. Rheumatoid arthritis causes synovitis of the MCP joint, which then leads to attenuation or rupture of the sagittal bands. Traumatic injury may involve a laceration of the hood, direct blow, or forced flexion of the MCP joint. In a closed injury, the finger is often forced into a flexed and ulnarly deviated position against a tense extensor muscles, causing a tear in the radial sagittal fibers. “Boxer’s knuckle,” a direct impact over the MCP joint with a clenched fist, has also been described as a mechanism of injury. Spontaneous subluxation secondary to an underlying laxity of the joint capsule may occur during simple activities of daily living. The rare case of congenital extensor tendon subluxation involves an ulnar drift of all the fingers, and is sometimes part of the entity known as a “windblown hand.”11

Classification

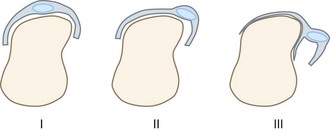

Rayan and Murray12 described three clinical types of sagittal band injuries. Type I injury is a contusion without tearing of the retinaculum, and demonstrates no instability. Type II is a moderate injury with extensor tendon subluxation, while type III is a severe injury with tendon dislocation (Figure 33-5). Subluxation was defined as “lateral displacement with painful snapping of the extensor tendon with its border reaching beyond the mid-line, but remaining in contact with the condyle during full MP joint flexion.” Dislocation was defined as “displacement of the tendon in the groove between the two metacarpal heads.”

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a sagittal band injury is primarily based on clinical findings and can be identified with a thorough review of history and physical examination. Closed injuries typically present with pain, swelling, and/or ecchymosis of the involved MCP joint. Open injuries will involve a laceration over the MCP joint, typically on the radial side. The extensor tendon may dislocate ulnarward into the intermetacarpal space, and the patient may complain of catching, locking, or snapping. It should be noted, however, that tendon displacement is often be obscured by swelling. Partial ruptures of the radial sagittal band will not present with subluxation of the extensor tendon. Active extension may produce ulnar angulation of the MCP joint and supination of the finger. With time, the ulnar deviation deformity prevents dorsal relocation of the extensor tendon, and the patient may be unable to extend the joint (Box 33-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree