Yeast Infections: Candidiasis, Tinea (Pityriasis) Versicolor, and Malassezia (Pityrosporum) Folliculitis: Introduction

|

Candidiasis

The genus Candida is comprised of a heterogeneous group of over 200 yeast species.1 Candida species are ubiquitous yeast-like fungi that form true hyphae, pseudohyphae, and budding yeasts. Candidiasis (or candidosis) refers to a diverse profile of yeast infections caused by members of the genus Candida, and predominantly by Candida albicans. Candida species are among the most common fungal pathogens to affect humans. While the skin, nails, mucous membranes, and gastrointestinal tract are typical sites of infection, Candida may involve any part of the body. Although considered opportunistic human pathogens, Candida species may also exist as commensal organisms of skin and mucosal membranes of the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory tracts.

Candida are usually limited to human and animal hosts, however they have also been recovered from the hospital environment: countertops, air-conditioning vents, floors, respirators, and on medical personnel. Oropharyngeal colonization with Candida is observed in up to 50% of healthy individuals 2 and may also be detected in 40%–65% of normal stool samples. In addition, C. albicans exists as a commensal organism in the vaginal mucosa of 20%–25% of asymptomatic, healthy women3 and up to 30% of healthy pregnant women.4 Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VC) is the second most common cause of vaginitis in women.

Candida species are the most common cause of fungal infection in immunocompromised persons. More than 90% of persons infected with HIV not receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) develop oropharyngeal candidiasis and 10% of these patients develop esophageal candidiasis.5–6 Candida species are now the fourth most commonly isolated pathogens from blood cultures in patients with systemic infections.7

Most candidal infections are mucocutaneous. While in few cases there may be pronounced effect on morbidity, these infections do not lead to death. However, immunocompromised patients including hospitalized patients, may develop candidemia and disseminated candidiasis which have a 30%–40% mortality rate. In fact, systemic candidiasis causes more case fatalities than any other systemic mycosis.

Neither sex is predisposed to candidal colonization.

Neonates and adults >65 years of age are most susceptible to candidal colonization and mucocutaneous candidiasis.

Responsible for 50%–60% of all candidal infections, C. albicans is the most common candidal pathogen identified.8 C. albicans has its own virulence factors including adhesion molecules that permit attachment of the organism to other structures, proteinase secretions [aspartyl proteinases (SAP1-9)] that facilitate damage to cell envelopes, as well as the ability to convert to the hyphal form which is thought to be important for the virulence of C. albicans.9

The relative prevalence of C. albicans in clinical isolates is declining, and other species such as Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis,1,10 Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei,1,11 and Candida dubliniensis12 are increasingly being encountered as pathogens.13 C. glabrata and C. albicans account for approximately 70%–80% of Candida species recovered from patients with candidemia or invasive candidiasis. Other species of Candida have gained importance because of their frequent intrinsic resistance to systemic antifungal therapy. Certain patient populations are more susceptible to specific Candida species: the presence of C. parapsilosis should be considered in hospitalized patients and those with vascular catheters or prosthetic devices, while Candida tropicalis has been observed to cause candidemia in patients with leukemia and in those who have undergone bone marrow transplantation.

![]() Importantly, host defenses and iatrogenic causes both play a significant role in the development of candidal infections.14 Associational and causal factors predisposing to Candida infection are outlined in Table 189-1.

Importantly, host defenses and iatrogenic causes both play a significant role in the development of candidal infections.14 Associational and causal factors predisposing to Candida infection are outlined in Table 189-1.

MECHANICAL FACTORS

|

NUTRITIONAL FACTORS

|

PHYSIOLOGIC ALTERATIONS

|

SYSTEMIC ILLNESSES

|

IATROGENIC

|

Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

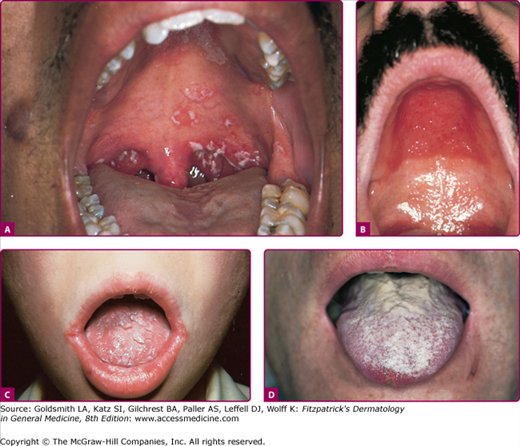

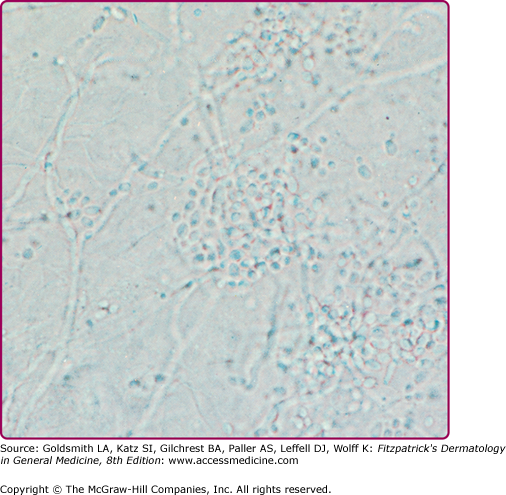

Acute pseudomembranous candidiasis or thrush is the most common form of oral candidiasis. Predisposing factors include diabetes mellitus, systemic steroid and antibiotic use, pernicious anemia, malignancy, radiation to head and neck, and cell-mediated immunodeficiency2,15–16 (Table 189-1). Thrush appears as discrete white patches that may become confluent on the buccal mucosa, tongue, palate, and gingivae (Fig. 189-1A). This friable pseudomembrane resembles cottage cheese or milk curds and consists of desquamated epithelial cells, fungal elements, inflammatory cells, fibrin, and food debris (Figs. 189-1A–189-1C). Scraping the patches exposes a brightly erythematous surface underneath. Microscopic examination of this material reveals masses of tangled pseudohyphae and blastospores (Fig. 189-2). In severe cases, the mucosal surface may ulcerate.

Figure 189-1

A. Pseudomembranous candidiasis or thrush. Note the characteristic white patches on the palate. B. Atrophic candidiasis under dentures. Edema and erythema at the site of contact with dentures. C. Candida perlèche with erythema and fissuring at the corners of the mouth. D. Hyperplastic candidiasis of the tongue.

Acute atrophic candidiasis (erythematous candidiasis), which occurs after sloughing of the thrush pseudomembrane,15 is observed most often in the setting of broad-spectrum antibiotic or systemic glucocorticoid therapy and human immunodeficiency virus infection.2 The most common location is on the dorsal surface of the tongue, where depapillated atrophic patches with minimal pseudomembrane formation are noted. There are both asymptomatic and symptomatic variants, the latter characterized by burning or pain.17

Chronic atrophic candidiasis (denture stomatitis) (Fig. 189-1B) is a common form of oral candidiasis seen in 24%–60% of denture wearers,18 and more commonly occurs in women. Chronic erythema and edema of the palatal mucosal surface in contact with the dentures is present. Presumably, the chronic low-grade trauma and occlusion caused by dentures predispose to candidal colonization and subsequent infection.19

Candidal cheilosis (angular cheilitis or perlèche) is characterized by erythema, fissuring, maceration, and soreness at the angles of the mouth (Fig. 189-1C). This condition is commonly encountered in habitual lip lickers and in elderly patients with sagging skin at the oral commissures. Loss of dentition, poorly fitting dentures, malocclusion, and riboflavin deficiency also predispose one to cheilosis. Cheilosis is often associated with chronic atrophic candidiasis in denture wearers.15

The differential diagnosis for oral candidiasis is summarized in Box 189-1.

Most Likely

Consider

Rule Out

|

VC is the second most common cause of vaginitis, and approximately three-fourths of all women will experience an episode of VC in their lifetime. C. albicans causes 80%–90% of VC and is followed by C. glabrata in frequency.20 Risk factors for VC include systemic antibiotic or steroid use, diabetes mellitus, presence of an intrauterine device, wearing of tight-fitting and synthetic clothing, and immunosuppression.21,22 These factors disrupt vaginal flora of lactobacilli that serve to inhibit overgrowth of Candida.20

Recurrent VC, defined as four or more episodes per year, occurs in up to 10% of women.20 Changes in hormone levels during pregnancy and the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may induce relapses. Use of genital cleansing solutions or douche may elicit a hypersensitivity response and increase susceptibility to Candida. Frequent sexual intercourse, resulting in vaginal abrasions and involving semen allergy, may also predispose women to recurrent VC.23 When none of the above mentioned factors is involved in VC, one should consider use of antibiotics, immunosuppression, or diabetes mellitus as potential contributors.24

Patients with VC present with a vaginal discharge associated with vulvar pruritus, burning, and occasional dysuria or dyspareunia. Examination shows thick curd-like whitish plaques on the vaginal wall with underlying erythema and surrounding edema that may extend to the labia and perineum. The cervix is normal upon speculum examination.25

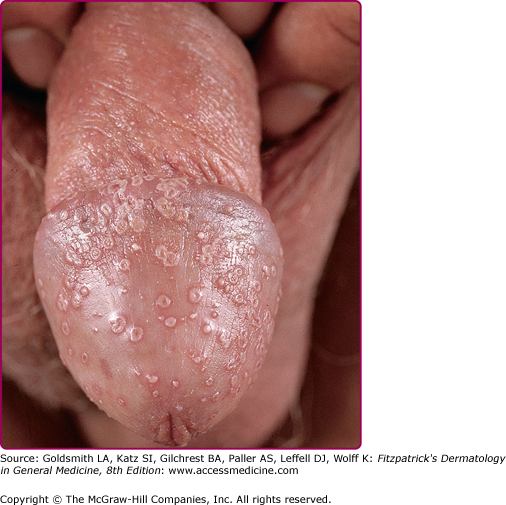

Candida spp. cause 30%–35% of infectious balanitis. Factors predisposing to candidal balanitis include diabetes mellitus, an uncircumcised state, and candidal vaginal infection in sexual partners. Occasionally, patients with balanitis complain of transient erythema and burning occurring shortly after intercourse. The eruption involving the penis is pruritic. Physical findings include white patches on the glans or prepuce. Small papules or fragile vesiculopustules on the glans or along the coronal sulcus (Fig. 189-3) break to leave erythematous erosions with a collarette of whitish scale. Infection may spread to the scrotum, gluteal folds, buttocks, and thighs. In diabetic or immunosuppressed patients, a severe edematous, ulcerative balanitis may occur.

Cutaneous Candidiasis

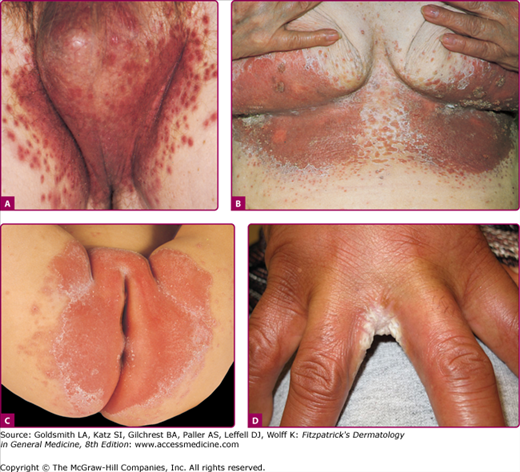

C. albicans has a predilection for colonizing skin folds, intertriginous zones in which the local environment is moist and warm. Usual locations for candidal intertrigo include the genitocrural, gluteal, interdigital, inframammary (Fig. 189-4) areas, and beneath the pannus and axillary areas. Predisposing conditions include obesity, diabetes mellitus, wearing of occlusive clothing and occupational factors.26 The pruritic eruption appears as macerated red erythematous patches and thin plaques with satellite vesiculopustules. These pustules enlarge and rupture, leaving an erythematous base with a collarette of easily detachable scale that contributes to further maceration and fissuring. Cutaneous candidal infection is diagnosed by the typical appearance of the eruption and confirmed by KOH examination and, when necessary, culture. See Box 189-2 for the differential diagnosis of intertriginous candidiasis.

Figure 189-4

Candidal intertrigo. A. Erythematous, eroded, pustular papules coalescing to plaques involving the scrotum and inguinal area with satellite lesions. Collarette-like scales where pustules have eroded. B. Confluent and discrete erythematous, eroded areas with pustular and erosive satellite lesions. C. Red, partially eroded plaques on the vulva surrounded by a delicate collarette in an infant. Outside the main lesions are a few pustular satellite lesions. D. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Erythematous eroded areas between the fingers.

Most Likely

Consider

Rule Out

|

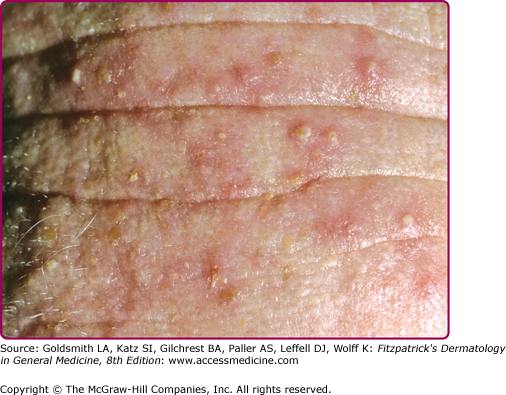

Several clinical variants of Candida intertrigo deserve special mention. Candidal diaper dermatitis results from yeast colonization of the gastrointestinal tract and chronic occlusion with wet diapers. The eruption with pronounced red erythema first appears in the perianal region and spreads to the perineum and inguinal creases (Fig. 189-4C).27 Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica refers to interdigital candidal or polymicrobial infection of the hands or feet, usually affects the third or fourth interdigital space, where moisture trapping is thought to underlie the condition (Fig. 189-4D). Candida miliaria affects the back in bedridden patients. The eruption begins as isolated vesiculopustules containing yeast, which spread over occluded regions on the back. Candida also colonizes and infects skin around wounds covered with occlusive dressings (Fig. 189-5). Broad-spectrum topical antibiotics contribute to these Candida wound infections.28

This is an unusual form of cutaneous candidiasis that manifests as a diffuse eruption beginning as individual vesicles and spreading into confluent areas involving the trunk, thorax, and extremities. The associated generalized pruritus is increased in severity in the genitocrural folds, anal region, axillae, and hands and feet (Fig 189-6).

Superficial infection involving the infundibulum of hair follicles occurs also in the predisposed patient, most commonly in the setting of diabetes mellitus or immunocompromised states. KOH examination of the contents of follicular pustules distinguishes this condition from bacterial folliculitis.

Candidal infection of the nails and paronychial folds occurs most often in those with diabetes mellitus or who habitually immerse their hands in water (i.e., housekeepers, bakers, fishermen, and bartenders). In paronychia, there is initial redness, swelling and tenderness of the proximal and lateral nailfolds with retraction of the cuticle toward the proximal nail fold (Fig. 189-7). Pain and erythema may extend along the entire nail plate and nail bed.29,30 Candidal paronychia should be differentiated from acute bacterial paronychia or paronychia associated with hypoparathyroidism, celiac disease, acrodermatitis enteropathica (Chapter 130), reactive arthritis syndrome (Chapter 20), acrokeratosis paraneoplastica, and retinoid therapy. Candidal onychomycosis is associated with secondary nail thickening, ridging, whitish discoloration, and occasional nail loss.

Figure 189-7

Chronic onychia and paronychia caused by Candida albicans. A. Note the warm but not hot, slightly tender, edematous nail fold with some onycholysis. This is very often misdiagnosed as staphylococcal paronychia. B. This is a chronic inflammatory condition with pustulation of the nail fold that also can involve the nail plate.

Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) is characterized by chronic, treatment-resistant, superficial candidal infections of the skin, hair, nails, and mucous membranes. There is virtually no propensity for disseminated visceral candidiasis.

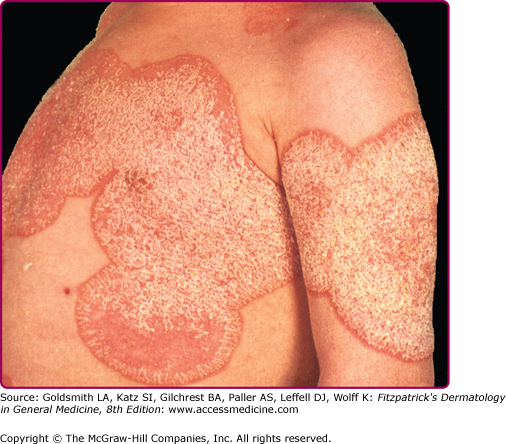

CMC is frequently associated with endocrinopathies including hypoparathyroidism, hypoadrenalism, and hypothyroidism, as well as conditions associated with specific abnormalities in cell-mediated immunity, such combined immune deficiency syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome, or patients with severely impaired T-cell function (i.e., AIDS). CMC first appearing in adulthood is often associated with thymoma.31 There are several more or less distinct clinical syndromes of CMC (Table 189-2)32–34 in which candidal infections cause oral thrush, diaper dermatitis, angular cheilitis (perlèche), lip fissures, nail and paronychial involvement, vulvovaginitis, and cutaneous involvement. The cutaneous eruption may appear with an erythematous, serpiginous border, or areas of brownish desquamation on a background of mild erythema (Fig. 189-8). Nail involvement is characterized by markedly thickened and dystrophic nail plates in which the entire thickness is invaded by Candida. The paronychial folds are red and edematous, there may be pus, and the fingertips are often bulbous (Fig. 189-7B).

Clinical Syndrome | Inheritance | Age at Onset | Distribution of Lesions | Endocrinologic Abnormality | Associated Findings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chronic oral candidiasis | Sporadic | Any | Mucosa of tongue, lips, buccal cavity; perlèche; no skin or nail involvement | None | Esophagitis | Denture stomatitis is a variant |

Chronic candidiasis with endocrinopathy (APECED) | Autosomal recessive | Childhood | Mucous membranes, skin, and/or nails | Frequent (hypoadrenalism, hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, or polyendocrinopathy) | Alopecia totalis, thyroiditis, vitiligo, chronic hepatitis, pernicious anemia, gonadal failure, malabsorption, diabetes mellitus | Endocrinopathy may be delayed in onset |

Chronic candidiasis without endocrinopathy | Autosomal recessive | Childhood | Mucous membranes, perlèche, and nail involvement; less common skin involvement | None | Blepharitis, esophagitis, laryngitis | – |

Autosomal dominant | Childhood | None | Dermatophytosis, loss of teeth, recurrent viral infections | – | ||

Chronic localized mucocutaneous candidiasis | Sporadic | Childhood | Mucous membranes, skin, and/or nails | Occasionally | Pulmonary infections, esophagitis | Hyperkeratotic lesions (Candida), granuloma |

Chronic diffuse candidiasis | Autosomal recessive | Childhood | Widespread on mucous membranes, skin and nail involvement Widespread on mucous membranes, skin and nail involvement | None | – | Erythematous, serpiginous skin lesions |

Adolescence | None | History of frequent course of antibiotics | – | |||

Chronic candidiasis with thymoma | Sporadic | Adulthood (after third decade) | Mucous membranes, nails, and skin | None | Thymoma, myasthenia gravis, aplastic anemia, neutropenia, hypogammaglobulinemia | Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis often precedes diagnosis of thymoma |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree