White Lesions

Libby Edwards

White skin color can occur in several different circumstances, with several different implications. In the past, white discoloration of a mucous membrane was called “leukoplakia,” and this was believed to be a precancerous lesion. Although squamous cell carcinoma and squamous dysplasia are often white, by no means do all white diseases confer an increased risk of malignant transformation.

White color can occur from a decrease in melanin. Another common cause of white skin is a thick epidermis with thick layer of scale/keratin that is hydrated. Just as palms and soles become white when exposed to water for an extended time, thick skin of warts or lichenification are often white when wet. Sometimes the abundant keratin of thick skin is not on the surface but trapped under the skin, as occurs with an epidermal cyst, which can look white. Exudate on the base of an ulcer sometimes appears white.

White Patches and Plaques

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is the only acquired condition that consists of the complete loss of pigment, or depigmentation, of the skin, rather than hypopigmentation, the partial loss of color. At times, this distinction is difficult to judge. A Wood light differentiates these two states, with depigmentation appearing bright white and hypopigmentation showing little difference compared to surrounding unaffected skin. This is a common condition, occurring in 1% to 2% of the population worldwide, although it is much more easily recognized in individuals of natural darker complexions. In addition to the cosmetic concerns of this condition, there is enormous stigma associated with white patches in some cultures, where Hansen disease (leprosy) can present with white areas.

Clinical Presentation

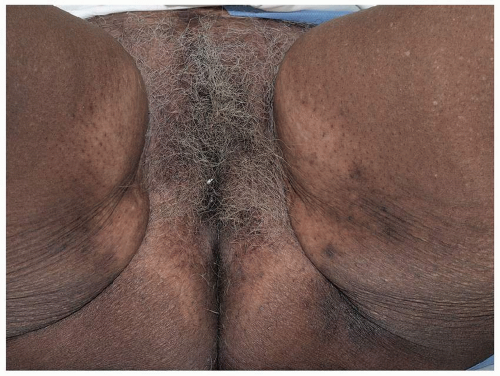

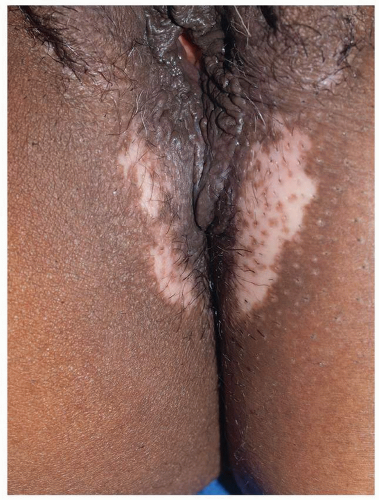

Vitiligo is characterized by milk-white skin with no evidence of any texture change. There is no crinkling, roughness, scale, lichenification, smoothness, or shininess (Figs. 8.1, 8.2 and 8.3). The borders of the depigmented skin are sometimes hyperpigmented. Patients usually present with extragenital lesions in the summer months when the areas burn or become more noticeable because of tanning of surrounding unaffected skin. There is a predilection for body sites that are often irritated or injured (called the Köebner phenomenon), such as the external genitalia, skin over the metacarpal joints, and around the mouth. The pigment loss can be patchy or extensive and confluent. The hairs in affected areas may lose their pigment and remain white even after spontaneous recovery of the skin.

The last melanocytes to disappear and the first to reappear are at the base of hair follicles, so that skin-colored, relatively brown macules are apparent within the patches (Fig. 8.4). In active vitiligo, depigmentation, normal skin color, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation may all occur, producing trichrome vitiligo (Fig. 8.5). Widespread vitiligo can be difficult to differentiate from hyperpigmentation (Fig. 8.6).

There are two forms of vitiligo, segmental, which is unilateral occurring at a young age, and nonsegmental, which is generalized, bilateral running a chronic and unpredictable course. Patients with generalized vitiligo exhibit an increase in other autoimmune diseases, especially thyroid disease, and have more circulating autoantibodies in general.

Pathophysiology

Although there are various theories for the origin of vitiligo, an autoimmune etiology is the most prominent, with genetic factors. Vitiligo is associated with autoimmune hypothyroidism, alopecia areata, lichen sclerosus, and halo nevi, all autoimmune conditions, as well as increased autoantibodies compared to unaffected individuals. Cytotoxicity from neurotransmitters has been suggested, and even vitamin D deficiency (1,2).

Occupational vitiligo can occur in the genital area in men as a result of destruction of melanocytes by exposure to para-tertiary-butylphenol, a substance found in resins for adhesives in the car industry.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of vitiligo is made clinically by the presence of depigmentation and the absence of textural change. A biopsy may be necessary in some cases.

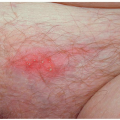

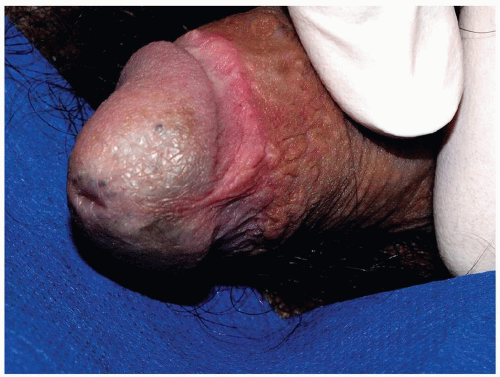

FIG. 8.1. This man with scrotal vitiligo also has depigmentation of his fingertips. The patches are well demarcated and consist of color change only. |

Histopathologically, there is an absence of melanocytes and melanin in the epidermis. This can be difficult to discern on routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, but incubation with 0.01% 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (also called dopa) stains enzymatically active melanocytes black in the basal layer, and electron microscopy can demonstrate the loss of the melanocytes. There is also a mild to moderate dermal lymphocytic infiltrate at the borders of some lesions, and melanocytes in this area often appear large with long dendrites containing melanin.

Confusion of vitiligo with postinflammatory hypopigmentation can arise, particularly in the early lesions of vitiligo. This can be an especially difficult differentiation in black patients with hypopigmentation as a postinflammatory sequela of the original inflammatory condition, for example, eczema or psoriasis. At times, the inflammation of skin diseases and injury of rubbing and scratching can precipitate vitiligo in predisposed patients, making the diagnosis more difficult in the setting of additional skin disease. The main differential diagnosis in the anogenital area is lichen sclerosus. This has a similar marble white color, but the textural changes in the skin of lichen sclerosus help to differentiate these conditions. In addition, vitiligo and lichen sclerosus are known to occur together. The anesthetic, hypopigmented patches of leprosy may also mimic vitiligo, but testing for sensation within the

white skin is normal in vitiligo. Vitiligo-like change can be induced by the topical immunomodulatory cream, imiquimod, used for treating genital warts (3).

white skin is normal in vitiligo. Vitiligo-like change can be induced by the topical immunomodulatory cream, imiquimod, used for treating genital warts (3).

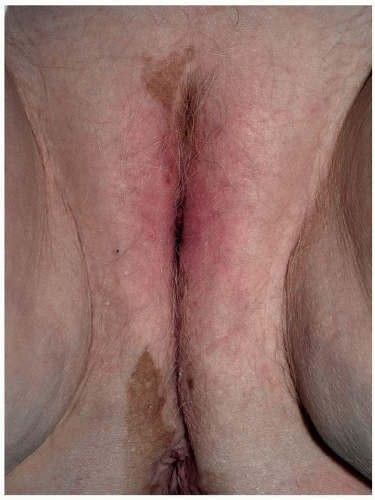

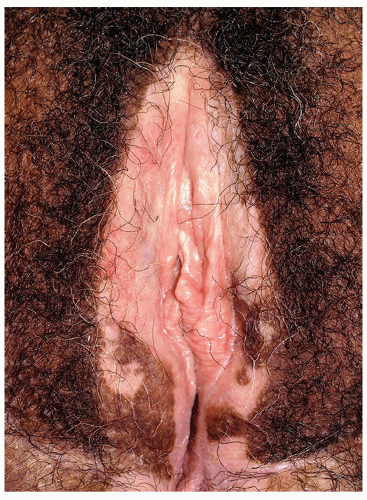

FIG. 8.2. When modified mucous membranes are involved, lichen sclerosus is suspected; however, there is no texture change, loss of architecture, or symptoms of itching or pain. |

FIG. 8.3. Vitiligo is common in children, as seen in the child with penile patches and coalescing macules on the scrotum. |

FIG. 8.4. This milk-white patch exhibits the skin-colored macules of brown color from the base of follicles, the last melanocytes to be affected and the first to recover. |

FIG. 8.5. At times, vitiligo can appear with different stages of depigmentation, called trichrome vitiligo. |

VITILIGO

Diagnosis

White, well-demarcated depigmented patches

No scale, surface change, or texture change of any kind

Biopsy generally not necessary, and routine histology is often normal; may require dopa stains to confirm absence of melanocytes

Management

Treatment of vitiligo on the genitalia generally is not requested by patients, and successful repigmentation on genitalia is uncommon. Treatment to encourage repigmentation in vitiligo includes medical and surgical therapies. Medical treatment includes a trial of a potent topical corticosteroid (i.e., clobetasol propionate or halobetasol propionate) for no longer than 8 weeks in a cycle (4). When there is some repigmentation with this therapy, cycles of a corticosteroid can be used, such as 6 weeks on and 6 weeks off. Care must be taken, particularly in the genitocrural folds, inner upper thighs, and scrotum as these areas are susceptible to steroid atrophy. Many providers also use a topical calcineurin inhibitor, tacrolimus (Protopic), or pimecrolimus (Elidel) twice a day, often in combination with the topical corticosteroid. These expensive medications are often not covered by insurance for this purpose but have no side effects of atrophy or steroid dermatitis (5). They may sting with application, and they are black-boxed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the unlikely events of squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Topical calcipotriol, a vitamin D analog, is sometimes used as well (6). More aggressive therapies that are not routinely used include epidermal grafts from suction blisters (7), dermabrasion (8) (which runs the risk of worsening vitiligo due to the Köebner phenomenon), and phototherapy (4) (which confers an increased risk for actinically induced skin cancers). The 308-nm excimer laser has been used but appears to be less effective than calcineurin inhibitors (9). A Cochrane review shows that data are derived from poorly designed trials and only corticosteroids and phototherapy show actual benefit (4).

Patients with vitiligo sometimes experience severe psychological repercussions, and these individuals often benefit from counseling. People with vitiligo that is widespread or cosmetically disfiguring can be treated by depigmentation therapy, where 20% monobenzylether of hydroquinone is used to depigment normal skin. Support and reassurance are generally the most effective course for genital vitiligo.

VITILIGO

Management

No satisfactory therapy for repigmenting the genital area, but the following are occasionally useful, alone or in combination:

Topical ultrapotent corticosteroid ointment applied b.i.d. in 6- to 8-week pulses

Tacrolimus or pimecrolimus applied b.i.d. ongoing

Calcipotriol (calcipotriene) cream applied b.i.d.

Ultraviolet light not practical or safe for genitalia and confers risk of malignancy

When large areas of the body are affected, remaining normal skin can be depigmented permanently with 20% monobenzylether of hydroquinone applied twice a day to even the skin color.

Postinflammatory Hypopigmentation

Clinical Presentation

Injury or inflammation of the skin can produce either hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Hypopigmentation can be mild or marked, and usually there is a history of a preceding event. Poorly demarcated hypopigmentation occurs in the distribution of the preceding inflammation or injury (Fig. 8.7). The loss of pigment is often very subtle, and usually there is no associated surrounding hyperpigmentation. When the injury is severe, the borders may be well demarcated.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can usually be determined by the pattern of hypopigmentation in association with the past or present existence of skin disease or injury. However, patients often either forget previous events or were unaware of them, so the lack of a consistent history is common. A biopsy is only occasionally required and shows a decreased amount of melanin in the basal keratinocytes, but melanocytes are present. Pigmentladen macrophages may be present in the underlying dermis.

The pallor of lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and lichen simplex may be similar to and coexist with postinflammatory hypopigmentation, but the textural changes and scarring help to distinguish these disorders. Vitiligo due to depigmentation can mimic postinflammatory hypopigmentation and Wood lamp examination can usually differentiate between the two.

Pathophysiology

Any inflammatory dermatosis or injury can leave residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation in the affected areas. The underlying cause of postinflammatory hypopigmentation is injury or destruction of the melanocytes. Generally, this is short-lived, and the melanocytes recover. Occasionally, scarring occurs and the color change is permanent. Permanent hypopigmentation also is a sequela of destructive treatments in which the melanocytes may be more susceptible to damage, as seen after cryotherapy or radiotherapy.

POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPOPIGMENTATION

Diagnosis

Pattern of hypopigmentation that correlates with past known or common inflammation or injury; diaper dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus, trauma of wart therapy, etc.

Pale, hypopigmented patches

No scale or surface change, except for that associated with any ongoing underlying etiologic inflammatory process

Biopsy generally not necessary for diagnosis; stains show presence of melanocytes

Management

There is no treatment for postinflammatory hypopigmentation other than treatment of or prevention of further dermatosis or injury. The normal skin pigmentation returns spontaneously to most with time.

POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPOPIGMENTATION

Management

Control of any ongoing underlying inflammatory process

Otherwise, self-resolving; no therapies hasten repigmentation

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is a relatively common disease with a predilection for the anogenital skin especially that of postmenopausal women. A recent small survey of people in a retirement facility found 2.3% with lichen sclerosus (10). The terms kraurosis vulvae and balanitis xerotica obliterans were used in the past, usually to describe advanced lichen sclerosus.

Clinical Presentation

The peak times of presentation of lichen sclerosus are childhood and later life, particularly after menopause. The classic presenting symptom is that of pruritus that can be excruciating, often associated with pain from erosions in the fragile skin due to rubbing and scratching or minor otherwise inconsequential trauma, including

sexual activity. Often, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic until an event such as a yeast infection produces symptoms that initiate irritation with resulting rubbing and scratching that perpetuates the inflammation and injury.

sexual activity. Often, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic until an event such as a yeast infection produces symptoms that initiate irritation with resulting rubbing and scratching that perpetuates the inflammation and injury.

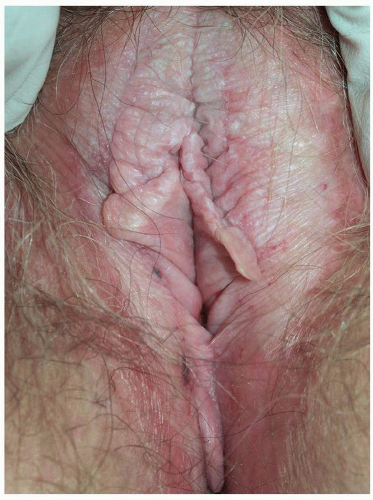

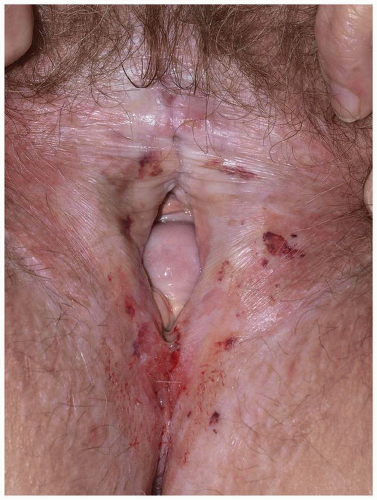

FIG. 8.8. This well-demarcated plaque of lichen sclerosus shows characteristic white color, shiny, crinkled skin, loss of labia minora, and puffiness of the clitoral hood. |

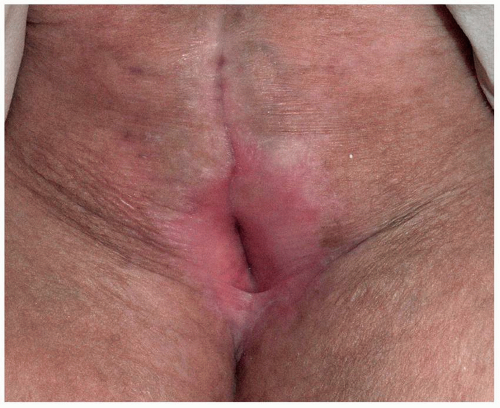

Constipation is a common presenting complaint in prepubertal girls, because lichen sclerosus around the rectal canal causes fissuring and painful defecation with consequent anal retention. Perianal involvement rarely occurs in male patients.

FIG. 8.9. The perianal location is typical of lichen sclerosus in women, although this is uncommon in men. The wrinkled texture is classic and diagnostic. |

FIG. 8.10. Lichen sclerosus frequently begins around the clitoral hood and perineal body, often resulting in scarring of the clitoral hood. |

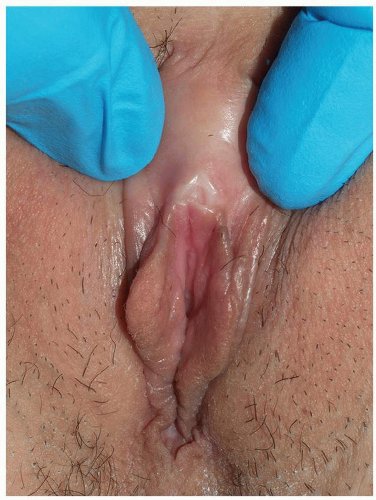

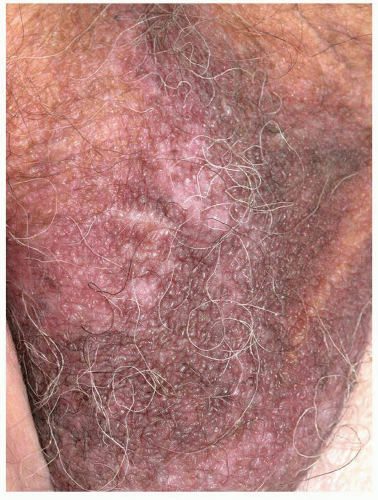

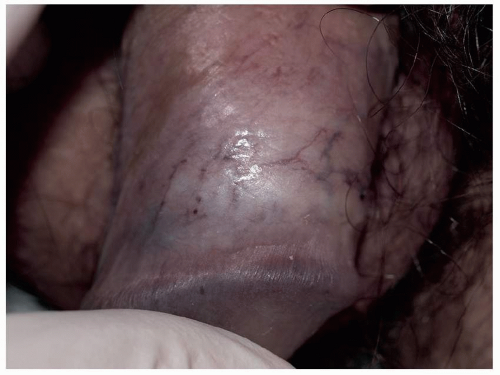

The classic findings of lichen sclerosus consist of white papules and plaques that are usually fairly well demarcated (Figs. 8.8 and 8.9). In women, lichen sclerosus often first and most prominently affects the clitoral area and perineal body (Fig. 8.10), with the entire modified mucous membranes and perianal skin becoming involved in some women, which many clinicians visualize as a figure-ofeight pattern. In the male, these occur on the glans and prepuce of the penis and less commonly the shaft (Figs. 8.11 and 8.12). Occasionally, the scrotum is affected (Fig. 8.13). Although hypopigmentation occurs in many skin disease, the texture of lichen sclerosus is a strong diagnostic clue. The skin surface classically shows fine wrinkling, a reliable sign of lichen sclerosus (Fig. 8.14). At times, the skin can be shiny and smooth, waxy, or hyperkeratotic and rough,

but there are always texture changes (Figs. 8.15, 8.16 and 8.17). Ecchymoses when seen are extremely suggestive of lichen sclerosus, because the upper dermis is replaced with a hyalinized substance that is fragile and produces no protection for blood vessels (Fig. 8.18). These ecchymoses can be mistaken for evidence of abuse in young girls. Additional signs include erosions or ulceration due to the fragility of lichen sclerosus. Hyperkeratotic plaques occur at times, sometimes as a result of rubbing and scratching and sometimes spontaneously, which is worrisome for incipient differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (d-VIN or squamous cell carcinoma in situ) (Fig. 8.19).

but there are always texture changes (Figs. 8.15, 8.16 and 8.17). Ecchymoses when seen are extremely suggestive of lichen sclerosus, because the upper dermis is replaced with a hyalinized substance that is fragile and produces no protection for blood vessels (Fig. 8.18). These ecchymoses can be mistaken for evidence of abuse in young girls. Additional signs include erosions or ulceration due to the fragility of lichen sclerosus. Hyperkeratotic plaques occur at times, sometimes as a result of rubbing and scratching and sometimes spontaneously, which is worrisome for incipient differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (d-VIN or squamous cell carcinoma in situ) (Fig. 8.19).

FIG. 8.11. The glans is the most common area for male lichen sclerosus, and the white color and purpura are pathognomonic. |

FIG. 8.12. Less severe lichen sclerosus can be subtle, but the hypopigmentation and crinkled skin lines are characteristic of this condition. |

FIG. 8.13. Lichen sclerosus affects the scrotum at times, but unlike lichen sclerosus in females, perianal skin is rarely involved. |

In young boys, lichen sclerosus often presents with phimosis and is a major cause of medical circumcisions. The lichen sclerosus is often unrecognized

until the excised prepuce is examined histologically. Lichen sclerosus in males occurs almost exclusively in uncircumcised patients. White papules occur on the glans and ventral foreskin, producing the same white, fragile plaques that exhibit purpura. The shaft can be involved as well. Perianal skin involvement is generally absent.

until the excised prepuce is examined histologically. Lichen sclerosus in males occurs almost exclusively in uncircumcised patients. White papules occur on the glans and ventral foreskin, producing the same white, fragile plaques that exhibit purpura. The shaft can be involved as well. Perianal skin involvement is generally absent.

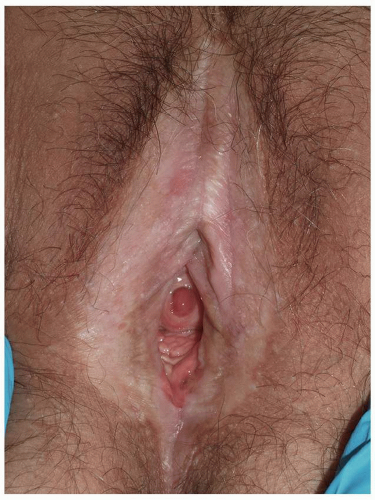

FIG. 8.16. Shiny, thin skin is another characteristic texture change for some patients with lichen sclerosus. |

Scarring is usual in more advanced disease; in women, this is manifested by resorption of the labia minora and scarring of the clitoral hood to the clitoris, with eventual sealing of the clitoral hood, or prepuce, concealing the glans clitoris underneath (Fig. 8.20). At times, the pocket formed under the clitoral hood becomes impacted with keratin debris of trapped keratinocytes shed from the surface of the epithelium, forming a pseudocyst (Fig. 8.21). Although usually asymptomatic, these pseudocysts can produce discomfort from distention and decrease sensitivity of the clitoris because of the accumulated keratin between the clitoris and the skin surface. Finally, rupture of the pseudocyst produces a brisk foreign body response, resulting in a painful, red nodule that may rupture and drain keratin and pus.

FIG. 8.17. At times, lichen sclerosus presents with thickened hyperkeratotic skin; this thick fragile skin tends to break instead of bending, producing fissures. |

Midline adhesions produce introital narrowing, but remarkable introital narrowing is not common. Lichen sclerosus spares mucosal, noncornified stratified epithelium of vagina, but there sometimes is involvement of the modified mucous membrane at junctional zones such as the vestibule. In the past, lichen sclerosus was believed to

never affect the vagina. However, in addition to one case report in the literature, this author has seen six patients with clinical and histologically confirmed lichen sclerosus of the vagina (Fig. 8.22). This usually, but not always, occurs overlying an exposed, prominent cystocele or rectocele in an area of squamous metaplasia.

never affect the vagina. However, in addition to one case report in the literature, this author has seen six patients with clinical and histologically confirmed lichen sclerosus of the vagina (Fig. 8.22). This usually, but not always, occurs overlying an exposed, prominent cystocele or rectocele in an area of squamous metaplasia.

FIG. 8.19. Localized white hyperkeratosis is fairly common with long-standing lichen sclerosus and this is sometimes a precursor to squamous cell carcinoma. |

Since lichen sclerosus is more likely to affect uncircumcised men, the scarring leads to a gradual tightening of the prepuce and eventually phimosis. The coronal sulcus can also become obliterated with adhesions (Fig. 8.23). Lichen sclerosus sometimes involves the cornified epithelium surrounding the urethral meatus and lower part of the urethra.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree