Introduction608

INTRODUCTION

Post-viral dermatoses

POXVIRIDAE

COWPOX

VACCINIA

Histopathology

Complications of vaccination

VARIOLA (SMALLPOX)

Histopathology

MONKEYPOX

Histopathology

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM

Treatment of molluscum contagiosum

Histopathology

Fig. 26.1

Fig. 26.2

MILKER’S NODULE

Histopathology

Fig. 26.3

Fig. 26.4

Electron microscopy

ORF

Histopathology

Fig. 26.5

Fig. 26.6

Fig. 26.7

Electron microscopy

Fig. 26.8

HERPESVIRIDAE

HERPES SIMPLEX

Treatment of herpes simplex

Histopathology

Fig. 26.9

Fig. 26.10

Fig. 26.11

Electron microscopy

Eczema herpeticum

Histopathology

VARICELLA

Histopathology

Electron microscopy

HERPES ZOSTER

Prevention and treatment of herpes zoster

Histopathology

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

Histopathology

Fig. 26.12

EPSTEIN–BARR VIRUS

Histopathology

HUMAN HERPESVIRUS-6

Histopathology

HUMAN HERPESVIRUS-7

HUMAN HERPESVIRUS-8

PAPOVAVIRIDAE (PAPILLOMAVIRIDAE)

VERRUCA VULGARIS

Treatment of verruca vulgaris

Histopathology510

Fig. 26.13

Fig. 26.14

Electron microscopy

PALMOPLANTAR WARTS

Histopathology

VERRUCA PLANA

Histopathology

Fig. 26.15

EPIDERMODYSPLASIA VERRUCIFORMIS

Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis

Histopathology609

Fig. 26.16

Fig. 26.17

CONDYLOMA ACUMINATUM

Treatment of condyloma acuminatum

Histopathology463

FOCAL EPITHELIAL HYPERPLASIA

Histopathology

BOWENOID PAPULOSIS

Treatment of bowenoid papulosis

Histopathology

Fig. 26.18

PARVOVIRIDAE

PARVOVIRUS B19

Histopathology744.745. and 747.

PICORNAVIRIDAE

HAND, FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

Histopathology

TOGAVIRIDAE

ROSS RIVER/BARMAH FOREST VIRUSES

Histopathology

Fig. 26.19

FLAVIVIRIDAE

WEST NILE FEVER/ENCEPHALITIS

Histopathology

DENGUE FEVER

Histopathology

HEPATITIS C VIRUS

PARAMYXOVIRIDAE

MEASLES

RETROVIRIDAE

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV)

Infections

Viral: molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, verruca vulgaris, condylomas, cytomegalovirus, oral hairy leukoplakia, Kaposi’s sarcoma

Bacterial: mycobacterial infections, more usual bacterial infections, bacillary angiomatosis

Spirochetal: syphilis

Fungal: candidosis, dermatophytosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, tinea versicolor, phaeohyphomycosis, nocardiosis, mucormycosis, Penicillium marneffei infection

Protozoa: acanthamebiasis, pneumocystosis

Arthropod: scabies, demodicosis

Neoplasms

Kaposi’s sarcoma, cutaneous lymphomas, Bowen’s disease, squamous and basal cell carcinomas, cutaneous melanomas

Dermatoses

Psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, acquired ichthyosis, asteatosis, porokeratosis, vasculitis, folliculitis, contact dermatitis, photosensitivity, vitiligo, yellow nail syndrome, papular eruption, idiopathic pruritus, a chronic diffuse dermatitis, severe drug reactions, alopecia, palmoplantar keratoderma, porphyria cutanea tarda, acrodermatitis enteropathica, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis

Histopathology864

HUMAN T-LYMPHOTROPHIC VIRUS TYPE 1 (HTLV-1)

OTHER VIRAL DISEASES

HEPATITIS A VIRUS

HEPATITIS B VIRUS

Gianotti–Crosti syndrome

KIKUCHI’S DISEASE

Histopathology926.935. and 936.

ASYMMETRIC PERIFLEXURAL EXANTHEM

Histopathology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Viral diseases

Viral infections of the skin are of increasing clinical importance, particularly in patients who are immunocompromised. Viruses may reach the skin by direct inoculation, as in warts, milker’s nodule, and orf, or by spread from other locations, as in herpes zoster. Many viral exanthems result from a generalized infection, with localization of the virus in the epidermis or dermis or in the endothelium of blood vessels. 1 The usual clinical appearance of this group is an erythematous maculopapular rash, but sometimes macular, vesicular, petechial, purpuric, or urticarial reactions may be seen. An erythematous-vesicular pattern is more likely to be a viral disease than the other causes of an exanthem such as drugs and bacteria. 2 Some of the varied manifestations of viral diseases may result from an immune reaction to the virus. This is the probable explanation for the erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum that occasionally follow viral infections. Other dermatoses appear to be in this category of a post-viral dermatosis (see below). A new exanthem with a distinctive erythematous macular appearance has recently been described. 3 It is of presumptive viral etiology but no organisms could be detected by the usual means. 3

Viruses are separated into families on the basis of the type and form of the nucleic acid genome, of the morphological features of the virus particle, and of the mode of replication. There are four important families involved in cutaneous diseases: the DNA families of Poxviridae, Herpesviridae, and Papovaviridae, and the RNA family Picornaviridae. In addition to these four families, exanthems can occur in the course of infections with the following families: Adenoviridae, Reoviridae, 4 Togaviridae, Flaviviridae, Retroviridae, Parvoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Arenaviridae, Filoviridae, and Bunyaviridae.1. and 5. The three major DNA families (there are seven in all) produce lesions that are histologically diagnostic for a disease or group of diseases, whereas the other viruses, particularly the RNA viruses, produce lesions that are often histologically non-specific. These non-specific features include a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, mild epidermal spongiosis, occasional Civatte bodies, and, sometimes, urticarial edema or mild hemorrhage. These features are often given the abbreviated title of morbilliform changes, but they can also be seen in drug eruptions. Although often regarded as favoring a drug reaction, eosinophils can certainly be found in viral exanthems, particularly in older lesions. LeBoit has highlighted these problems in a philosophical article a few years ago. 6 Inclusion bodies, which represent sites of virus replication, are uncommon in skin lesions produced by viruses outside the four major families.

Various laboratory techniques can be used to assist in the specific diagnosis of a suspected viral disease. 7 These include light and electron microscopy of a biopsy or smear, serology, viral culture, and immunomorphological methods. Negative-contrast electron microscopy allows rapid, and virus-family specific, detection of the causative virus. 8 Although viral isolation in tissue culture remains the paramount diagnostic method, the development of monoclonal antibodies to various viruses, for use with fluorescent, immunoperoxidase, and ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) techniques, has made possible the rapid diagnosis of many viral infections with a high degree of specificity. 9 Techniques using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are now being used routinely in some laboratories for the diagnosis of certain viral diseases. Serology is still the preferred method of diagnosis for certain viral infections, such as rubella and infectious mononucleosis. Brief mention must be made of the Tzanck smear, which was traditionally used by clinicians, especially dermatologists, in the diagnosis of certain vesicular lesions, especially those caused by the herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses. A smear is made by scraping the lesion. This is then stained by the Giemsa or Papanicolaou methods and examined for the presence of viral inclusion bodies. This use is declining with the advent of the more specific immunomorphological techniques.

The various virus families, and the cutaneous diseases they produce, will be considered in turn, after a brief discussion of the concept of the post-viral dermatoses.

Dermatoses are seen, occasionally, which appear to be a reaction to an earlier viral infection. As mentioned above, erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum sometimes follow a viral infection. At other times the viral etiology is presumptive, such as the appearance of skin lesions some days after an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infection of possible viral etiology. Serological evidence of a viral illness, such as IgM antibodies to a particular virus, is sometimes present. Although the dermatoses are thought to result from an immunological reaction to a virus, it does not necessarily persist in the body. There are circumstances in which viral persistence has been demonstrated. Such is the case with the herpes simplex virus and erythema multiforme (see p. 51).

The histological pattern seen in these various post-viral dermatoses is similar – a lichenoid lymphocytic vasculitis. This pattern is characterized by a lymphocytic vasculitis, usually mild and without the presence of fibrin in vessel walls, accompanied by a lichenoid (interface) reaction in which there are variable numbers of apoptotic keratinocytes. Variations on this theme may allow a specific diagnosis to be attached to the process. For example, some cases of pityriasis lichenoides appear to follow a viral illness. On histological examination, there is parakeratosis in addition to a lichenoid lymphocytic vasculitis. In erythema multiforme, associated with herpes simplex, there is a prominent lichenoid (interface) dermatitis with cell death at all layers of the epidermis. In Gianotti–Crosti syndrome (see p. 631), associated with many different viruses, spongiosis is an additional modification to the usual pattern of lichenoid lymphocytic vasculitis.

This concept may need to be modified as additional information becomes available. In the meantime, it provides a plausible explanation of observed cases.

The family Poxviridae is divided into many genera of which the genus Orthopoxvirus includes vaccinia virus, variola virus, cowpox virus, and at least six other species including monkeypox virus, camelpox virus, and raccoonpox virus.10.11. and 12. Only three other genera cause human disease: the genus Parapoxvirus causing milker’s nodule, orf, and sealpox;12.13. and 14. the genus/subgenus Molluscipoxvirus resulting in molluscum contagiosum; 15 and the genus Yatapoxvirus resulting in tanapox. The account that follows will be limited to the following poxvirus infections:

• cowpox

• vaccinia

• variola (smallpox)

• monkeypox

• molluscum contagiosum

• milker’s nodule

• orf.

The causative viruses are large, with a DNA core and a surrounding capsid. There are two subgroups, based on the morphological features of the virus. The viruses of molluscum contagiosum and orf are oval or cylindrical in shape and measure approximately 150 × 300 nm. The remaining viruses are brick-shaped and range in size from 250 to 300 nm × 200 to 250 nm. Clusters of these poxviruses can be identified in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections as intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions.

Cowpox is a viral disease of cattle. It may be contracted by milkers, who develop a pustular eruption on the hands, forearms or face, accompanied by slight fever and lymphadenitis. Crusted lesions resembling anthrax, 16 and sporotrichoid spread17 have also been reported. A generalized eruption due to cowpox infection may develop, rarely, in patients with atopic dermatitis.18. and 19. This variant, known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, resembles eczema herpeticum (see p. 616). The disease is of historical interest because it was the immunity to smallpox of those who had had cowpox that led Jenner to substitute inoculation with cowpox for the more dangerous procedure of variolation. Doubt has been cast recently on the role of cattle as a reservoir of infection in cowpox.16. and 20. It appears that the domestic cat and rodents have an important role in the transmission of cowpox virus.12.16.19.20.21.22. and 23. Rare cases continue to be reported from Europe24. and 25. and other parts of the world. 26 Rapid identification can be made by an orthopoxvirus-specific PCR. 25

Buffalopox is a similar condition, reported in persons who milk infected buffaloes. 27

Vaccination against smallpox was carried out with the vaccinia virus, a laboratory-developed member of the poxvirus group. In previously unvaccinated individuals, a papule developed on about the fifth day at the site of inoculation. This quickly became vesicular and gradually dried up, producing a crust which fell away, leaving a scar. Exaggerated scarring is a rare complication. 28 Hypersensitivity reactions, which may be exanthematous, urticarial, and erythema multiforme-like, may also develop. 29 Clinically detectable immunity appears to persist for at least 20 years after smallpox vaccination. 30

With the eradication of smallpox, vaccination is no longer given routinely, except to military and key medical personnel. 31 As a result, generalized vaccinia infection (eczema vaccinatum), 32 a serious complication of vaccination, is now of historical interest only. A review of 450 293 military vaccinations performed recently found no resulting cases of eczema vaccinatum and only 21 cases of contact transfer of vaccinia to close contacts. 33 Eczema vaccinatum has many similarities to eczema herpeticum, an infection by the herpes simplex virus seen also in predisposed patients, such as those with an atopic diathesis.

Vaccinia of the labia and inner thighs has been reported as a consequence of conjugal transfer of the virus, from military personnel who received smallpox vaccination. 34 Autoinoculation to another body site is another complication of vaccination. 35

The appearances are similar to those of herpes simplex, zoster, and varicella, except that intracytoplasmic rather than intranuclear inclusion bodies are seen in vaccinia.

Many cutaneous and systemic complications of smallpox vaccination have been reported.36. and 37. They are now of historical interest only, except for late complications, which may continue to be seen. 38

Late sequelae have included keloid formation, basal and squamous cell carcinoma, 39 malignant melanoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. 40 Dermatoses have also developed, including discoid lupus erythematosus, 41 herpes simplex, 38 lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, 42 contact dermatitis, and ‘localized eczema’. 37 It is possible that some of the late complications represent the chance localization of a particular lesion at the site of previous vaccination.

Variola (smallpox) epidemics have been some of the most deadly to afflict humankind. 31 Epidemics occurred in ancient China, Egypt, and India, and later in the Roman Empire. 31 Variola has now been eradicated. 43 The last known case occurred in Somalia in 1977. Two types were encountered: variola major, a severe form with a significant fatality rate (up to one-third of those affected), 44 and variola minor (alastrim), a mild form with a fatality rate of less than 1%. Umbilicated papules were seen. They became crusted and healed with scarring. The mechanism of the scarring remains speculative but it has been suggested recently that this may have resulted from destruction of sebaceous glands. 45

Variola remains a potential threat in biological warfare as laboratory cultures of the virus still exist. 46

Variola resulted in vesicular lesions that resembled those of herpes simplex, zoster and varicella, except (usually) for the absence of multinucleate epidermal cells and for the intracytoplasmic localization of the inclusion bodies. 47

Human monkeypox, an emerging viral zoonosis, is caused by a member of the genus Orthopoxvirus. It was first identified in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) in 1970. It emerged in the United States in 2003, probably as a consequence of the shipment of small animals from Ghana to the United States.48. and 49. Much attention was initially paid to monkeypox because of its clinical similarities to smallpox. 48

In Africa, monkeypox is mainly a disease of children younger than 10 years. Infection is caused mainly by contact with infected small mammals, although human-to-human transmission is not uncommon. 48 Vaccination and vaccinia virus produces about 85% protection against monkeypox. In the cases reported from the United States, all had contact with infected exotic or wild mammalian pets. No human-to-human transmission could be detected. No fatalities were recorded in the United States, although it is 10–17% in African cases. 48

At the edge of the blister there is spongiosis and acanthosis, while the blister itself is an intraepidermal bulla with ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes intertwined with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils, with a rare eosinophil. 49 There is progression of the lesion to full-thickness necrosis of a markedly acanthotic epidermis. Rare multinucleated keratinocytes are present but the nuclei do not show viral cytopathic changes. Follicular involvement occurs. 49 A pustular stage then ensues.

Eosinophilic Guarnieri-type intracytoplasmic inclusions are present in affected keratinocytes. A few nuclei may have a central ground-glass appearance mimicking the inclusions of herpesvirus infections, but no true intranuclear inclusions are present. Electron microscopy confirms that the virions are in the cytoplasm of keratinocytes. 49

Molluscum contagiosum is a poxvirus infection of the skin and mucous membranes caused by a virus in the subgenus Molluscipoxvirus, which comprises four genetically distinct, but clinically indistinguishable, viral subtypes. 15 Molluscum contagiosum occurs as solitary or multiple dome-shaped, umbilicated, waxy papules which range in size from 2 to 8 mm in diameter, although solitary lesions may be slightly larger. 50 There is a predilection for the head and neck, trunk, flexural areas, or the genitalia of children and adolescents.15.51.52.53.54.55.56. and 57. Uncommon sites of involvement include the toes, 58 penis, 59 tattoos,60. and 61. burned skin, 62 and herpes zoster scars. 63

Sexual and fomite transmission may occur.64. and 65. Use of swimming pools is associated with some infections. 66 Atopic dermatitis is present in more than 20% of infected patients. 15 One patient with atopic eczema developed erythema multiforme-like targetoid eczema around each lesion of molluscum contagiosum. 67 The coexistence of molluscum contagiosum and verruca plana has occurred in a patient with the hyper-IgE syndrome. 68 Molluscum contagiosum has also developed in patients receiving treatment with tacrolimus or methotrexate, for other diseases.69.70.71. and 72.

Spontaneous regression often occurs within a year, although more persistent lesions are encountered. This regression is primarily a cell-mediated immune response as there is usually an associated lymphocyte response. Pitted scarring is a rare complication of regression in atopic individuals. 73 Antibodies to the virus have been found in nearly 60% of patients with skin lesions, suggesting a role for humoral immunity, but antibodies are less frequent in patients with AIDS. 74 Extensive lesions can occur in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with AIDS.75.76.77.78.79.80.81.82.83. and 84. Disseminated lesions can occur in HTLV-1 infection as well. 85

An additional mechanism appears to be involved in regression. 86 This involves the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). Apoptosis of viral-infected cells appears to be the end-point of these various mechanisms of regression. The virus may try to evade apoptosis by expressing the MC159 protein, which inhibits CD95- and TTVFR-1-induced apoptosis. 86 Apoptosis is not increased in active lesions. 87 Attenuated ubiquitination of molluscum bodies has been reported in a patient with multiple lesions in the setting of malignant lymphoma. 88

The disease is caused by a large brick-shaped DNA poxvirus with an ultrastructural resemblance to vaccinia virus. 89 A well-defined sac encloses the virion colony of each infected keratinocyte. 90 The sequencing of the viral genome is known. 91 The diagnosis can be made in the clinic by the use of 10% potassium hydroxide preparations. 92

The treatment of molluscum contagiosum is varied, with no one modality favored in any country. Solitary lesions are often treated by shave or surgical excision, as the diagnosis may not have been made pre-treatment. Cryotherapy is another option. Sterilized tweezers have been used to remove lesions with some success. 93 Other modes of ‘enucleation’ are favored by some. A prospective randomized trial published in 2006 compared four common treatments: curettage, cantharidin, a combination of salicylic acid and glycolic acid, and imiquimod. 94 Curettage was found to be the most efficacious treatment and had the lowest rate of side effects. However, it is time-consuming and requires anesthesia. Two of the other treatments had side effects considered unacceptable for routine use while the fourth, imiquimod, was said to ‘hold promise’. 94 A study published in 2008, found that systemic drug levels were low in children after single and multiple doses of imiquimod 5% cream. 95 Cidofovir, a drug with broad-spectrum anti-DNA virus activity, has been successfully used in the treatment of recalcitrant lesions in patients with HIV.91. and 96. The injection of candida antigen into the lesion has been used as a form of immunotherapy. Complete resolution occurred in 56% of patients who were followed up. 97

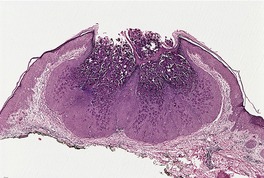

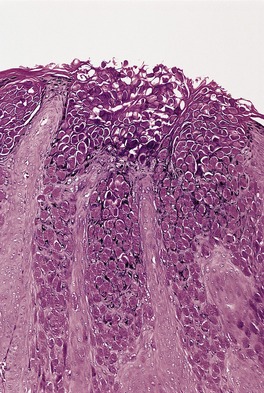

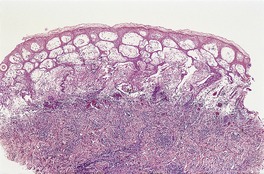

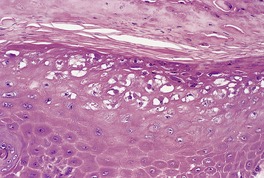

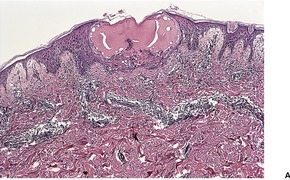

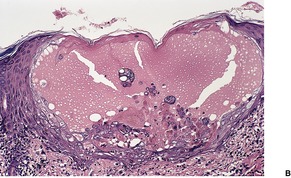

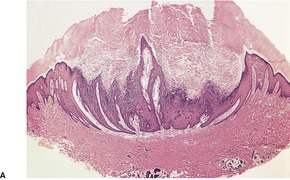

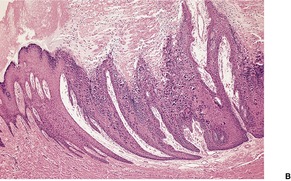

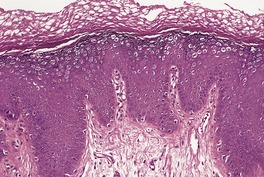

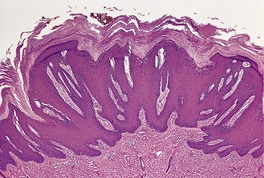

A lesion consists of several inverted lobules of hyperplastic squamous epithelium which expand into the underlying dermis (Fig. 26.1). 89 The lobules are separated by fine septa of compressed dermis. Eosinophilic inclusion bodies form in the cytoplasm of keratinocytes just above the basal layer, and progressively enlarge. At the level of the granular layer, the bodies become increasingly hematoxyphile and occupy the entire cell (Fig. 26.2). These molluscum bodies are eventually extruded with keratinous debris into dilated ostia, which lead to the surface.98. and 99. Areas of hair bulb differentiation, or epithelial proliferation mimicking a basal cell carcinoma, may occur at the margins of a lesion. 98 Molluscum contagiosum has been reported in epidermal cysts,89.100. and 101. but some of these cases may simply represent pilar infundibula dilated by cornified cells and molluscum bodies. 102

Molluscum contagiosum showing inverted lobules of squamous epithelium with molluscum bodies maturing toward the surface. (H & E)

Molluscum contagiosum. The large molluscum bodies occupy almost the whole of each infected cell. (H & E)

Secondary infection and ulceration may occur. 103 Molluscum folliculitis is an uncommon pattern seen mainly in immunocompromised persons. 104 It has also followed leg shaving. 105 The molluscum bodies are present within the follicular epithelium. A variable chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is seen in regressing lesions, and is thought to represent a cell-mediated immune reaction.98. and 106. However, in the early eruptive phase there is no inflammatory response. 107 Inflammation and a foreign-body reaction may also be related to extrusion of molluscum bodies into the dermis. Rarely, an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate (‘pseudoleukemia cutis’, ‘pseudolymphoma’) may be found.108.109.110. and 111. In one case, the atypical cells were CD8+ T lymphocytes with scattered CD30+ cells. 112 In another they were CD4+, with some CD30+ cells. 110 Another rare inflammatory response is a moderate to heavy infiltrate of eosinophils, with the formation of flame figures.113. and 114.

Molluscum contagiosum has also been reported in association with a nevocellular nevus, a halo nevus,115. and 116. with the Meyerson phenomenon (see p. 717), 117 with cutaneous lupus erythematosus118 and with human papillomavirus (HPV). 119 Co-infection with cryptococcosis has been reported in a patient with HIV infection. 120 In one patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, metaplastic bone was present in the dermis adjacent to each lesion of molluscum contagiosum. 121

Milker’s nodule results from infection with the paravaccinia virus, transmitted from the udders of infected cows. Indirect transmission from contaminated objects has also been reported in several patients with recent burns. 122 Lesions are usually solitary, and on the hands. 123 Multiple nodules and involvement of other sites have been described. Lesions heal, with scarring, in 6–8 weeks. Six clinical stages have been delineated, but the usual lesion, when the patient presents, is a red-violaceous, sometimes erosive or crusted nodule measuring 0.5–2 cm in diameter. 124 Erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, or urticarial lesions may develop in a small number of cases. 125

The clinical and histopathological similarities between milker’s nodule and human orf have led to the collective term ‘farmyard-pox’ being proposed for these two conditions. 126

Treatment is usually supportive. No trials of antiviral therapy have been published in the dermatological literature. Infection confers lifelong immunity to the host. 123

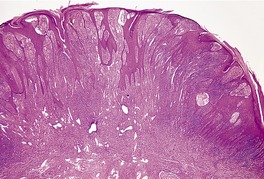

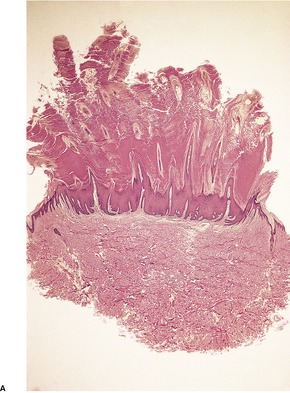

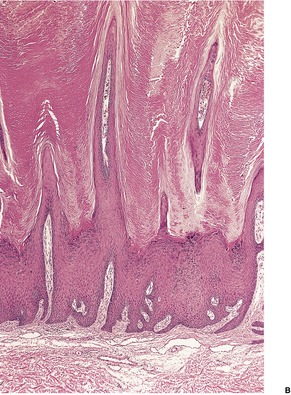

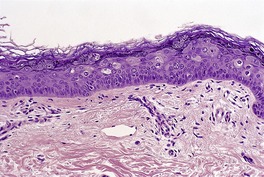

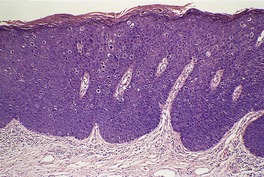

The appearances vary with the stage of the lesion. 124 An early milker’s nodule shows vacuolization and ballooning of the cells in the upper third of the epidermis, leading sometimes to multilocular vesicles. 127 Intracytoplasmic and, rarely, intranuclear inclusions may be seen. 128 Focal epidermal necrosis sometimes occurs, and this may lead to ulceration and secondary scale crust formation. Neutrophils are found in the epidermis and superficial papillary dermis when epidermal necrosis occurs. Mature lesions will show acanthosis of the epidermis, with the formation of finger-like downward projections of the epidermis (Fig. 26.3). There is prominent edema of the papillary dermis, with an inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and occasional eosinophils. There are numerous small blood vessels, many of which are ectatic, in the papillary dermis (Fig. 26.4). In regressing lesions there is progressive diminution of the acanthosis, and eventually of the inflammatory infiltrate. 124

Milker’s nodule. The elongated thin rete pegs with intervening heavy inflammation of the upper dermis are characteristic features of mature lesions. (H & E)

Milker’s nodule. The dermis between the thin rete pegs is vascular and inflamed. (H & E)

Electron microscopy may show a large oval viral particle with a central electron-dense core surrounded by a less dense homogeneous coat and two narrow electron-dense layers. Rapid diagnosis may be made by electron microscopy of the crust from an early lesion. 129

Orf (ecthyma contagiosum) is primarily a disease of young sheep and goats, involving the lips and perioral area.126.130.131.132.133.134.135. and 136. It is caused by a poxvirus of the paravaccinia subgroup. Orf can be transmitted to humans by contact with infected animals; rarely, lesions have developed at sites of trauma produced by an inanimate object. 135 Lesions, which measure approximately 1–3 cm or more132. and 133. in diameter, develop most commonly on the hands and forearms. Other sites of involvement have included the face,137. and 138. scalp, temple, 139 and perianal region. 134 Several lesions may be present in the one area. Spontaneous regression is usual after about 7 weeks. Recurrent lesions have been reported in immunocompromised persons; 140 such lesions may be quite large. 141 A mature lesion is nodular with central umbilication and an erythematous halo. Regional adenitis, superinfection, toxic erythema, erythema multiforme, widespread lesions, or a generalized varicelliform eruption may complicate the infection. 142 Bullous pemphigoid, mucous membrane pemphigoid, 143 and a subepidermal blistering disease that was thought to be a distinct autoimmune blistering disorder144 may also develop following orf.145. and 146.

As spontaneous regression eventually occurs treatment is not usually given in cases where a clinical diagnosis is made. Many lesions are surgically excised or shaved as a diagnostic tool. As large and atypical lesions may develop in immunocompromised patients, multiple treatment modalities have been used in these patients with variable results. Surgical excision, 40% topical idoxuridine application, cryotherapy, interferon, topical cidofovir, and imiquimod 5% cream have all been used.

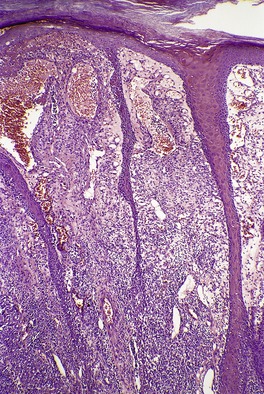

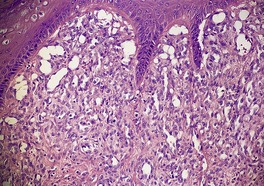

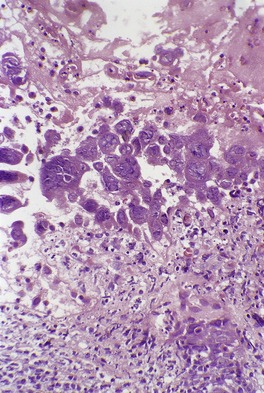

The appearances vary with the stage of the disease (Fig. 26.5).130. and 131. Early lesions of orf show moderate acanthosis and pale vacuolated cytoplasm, involving particularly the upper epidermis. 147 Cytoplasmic inclusion bodies are usually present (Fig. 26.6). 126 An unusual change, which has been called ‘spongiform degeneration’, can be seen, particularly in follicular structures. 126 This is characterized by vacuolated cells having wispy strands of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Intraepidermal vesicles or bullae may form. The dermis contains dilated thin-walled vessels and an infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and occasional eosinophils and plasma cells. 131 Cells expressing CD30 are sometimes present in this infiltrate. 148 Later lesions often show epidermal necrosis, particularly in the center. Neutrophils are often found within and adjacent to the necrotic epidermis. Other biopsies may show elongated rete pegs with dilated vessels in the intervening dermal papillae. Sometimes there is an unusual proliferation of endothelial cells in the dermal papillae which may even simulate a vascular tumor (Fig. 26.7). 139 Eventually the inflammatory infiltrate and epithelial hyperplasia resolve. The lesions of orf are generally regarded as indistinguishable from milker’s nodules, 126 although full-thickness epidermal necrosis seems to be more common in orf. Immunoperoxidase techniques using orf-specific monoclonal antibodies can be used to confirm the diagnosis, if necessary.

Orf. There is epidermal necrosis, acanthosis, and subepidermal edema. (H & E)

Orf. Inclusion bodies are present in the cytoplasm of the keratinocytes in the upper epidermis. (H & E)

Orf. The papillary dermis may be so vascular that a vascular tumor is suspected. (H & E)

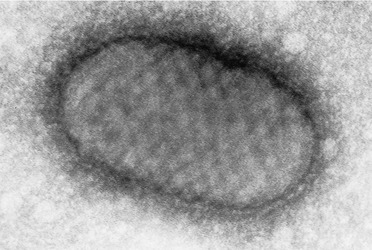

Electron microscopy shows an oval virus with an electron-dense core, surrounded by a laminated capsule similar to the virus of milker’s nodule (Fig. 26.8). 149 Rapid diagnosis may be made by electron microscopy of negatively stained suspensions from the lesion. The number of virus-containing cells is greatest in the first 2 weeks of the disease; they may be absent by the fourth week. 150

Orf. Ultrastructural features of the orf virus with its laminated capsule and internal cross-hatched appearance. (Electron micrograph ×20 000)

More than 80 herpesviruses have now been identified, eight of which are known human pathogens. 151 There are three major subgroups within the family Herpesviridae. The α-herpesviruses are neurotropic and include herpes simplex virus (types 1 and 2) and the varicella-zoster virus.152. and 153. The γ-herpesviruses, the second major subgroup within the family, are lymphotropic and include Epstein–Barr virus, human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8), and Herpesvirus saimiri. The predominant sites of latency of the third subgroup, the β-herpesviruses – cytomegalovirus and human herpesviruses 6 and 7 (HHV-6 and HHV-7) – are not known. 153 Concurrent infection by two viruses of this family is a rare occurrence, seen in immunocompromised patients.154. and 155.

Type-specific identification of the two main types of herpes simplex virus can be made in paraffin sections using immunoperoxidase techniques; furthermore, varicella-zoster virus can be distinguished from them.156. and 157. PCR techniques can also be used.154.158. and 159.

There are two main types of herpes simplex virus, type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2).151.160. and 161. Primary infection with HSV-1 usually occurs in childhood and is mild. Recurrent lesions occur most commonly around the lips (herpes labialis – ‘cold sores’). Other sites of infection include the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, eye, lung, and brain.162.163. and 164. Orofacial herpes is quite common with an annual prevalence of approximately 15%. 165 Its lifetime prevalence is close to 40%. 166 Women are more commonly affected than men. 165 It affects over 40 million people in the United States. 167

Infection with HSV-2 generally involves the genitalia and surrounding areas after puberty; it is usually sexually transmitted.168.169. and 170. Its occurrence in children may be a consequence of child abuse. 171 Approximately 1.6 million persons are infected with HSV-2 annually in the United States. 167 In one study, antibodies to HSV-2 were present in nearly 5% of sexually active Turkish individuals. 172 The incubation period for genital lesions averages 5 days. HSV-2 may also result in generalized or cutaneous lesions of the newborn.173. and 174. The relationship between the site of infection and HSV type is not absolute.175. and 176. Sometimes herpes simplex infection masquerades as some other disease. 177 It may also be difficult to diagnose in immunosuppressed patients. 167 Genital herpes has masqueraded as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in two immunosuppressed patients. 178

Once infected, a person will usually harbor the virus for life. The virus can travel along sensory nerves to infect the neurons in the sensory ganglia. Recurrent disease follows this latency in the sensory ganglia and can be stimulated by ultraviolet light, 179 trauma, fever, HIV infection, 180 menstruation, and stress, to name the most common factors. 181 Acute skin eruptions that are positive for HSV DNA polymerase are an increasing problem in patients who undergo stem cell transplantation. 182 No precipitating factors can be identified in some patients. 183 Prostaglandins and diminished production of IFN-γ may play a role in the reactivation of infections.184. and 185. A study some years ago found that reactivation of genital HSV-2 infection in asymptomatic seropositive persons is quite frequent. 186 Asymptomatic perianal shedding of HSV is common in patients with AIDS. 187

The usual lesions of herpes simplex consist of a group of clear vesicles which heal without scarring, except in cases where secondary bacterial infection supervenes. Leukoderma may develop on the lip after herpes labialis. 188 Special clinical variants189 include herpes folliculitis of the beard or scalp, herpetic whitlow190.191.192. and 193. (usually in medical or nursing personnel), necrotizing and ulcerative balanitis194. and 195. and vulvitis196 (a very rare HSV-2 complication, often associated with HIV infection), a varicella-like eruption, 197 infection localized to sites of atopic dermatitis, 198 pulsed-dye laser treatment, 199 or photoexposure, 200 vegetating plaques,201. and 202. hypertrophic papulonodules, 203 flaccid intracorneal blisters, 204 acquired lymphedema of the hand, 205 and eczema herpeticum (see p. 616). 206 Severe primary or secondary infection with systemic involvement may occur in immunocompromised patients.207. and 208. It has followed meningococcal meningitis. 209 Disseminated herpes simplex infection is a rare complication of pregnancy. 210 Recurrent herpes labialis has developed during treatment of acne with isotretinoin.211. and 212. Recurrences decreased after the application of sunscreens. 212 Herpes simplex virus DNA is present in lesional skin in a significant number of patients with erythema multiforme (see p. 51).213. and 214. Lymphedema of the hand is a rare complication of recurrent infection. 215

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are biologically and serologically distinct. They are usually isolated using human embryonic fibroblast cell cultures. 216 Characteristic cytopathic changes can be seen after 1 or 2 days. Rapid diagnosis of cutaneous infections of herpes simplex can be made using smears of lesions and monoclonal antibodies, with an immunofluorescence technique. 217 PCR-based tests are far more sensitive than immunofluorescence. 218 Reliable and convenient serological tests for antibodies against both HSV-1 and HSV-2 are now available commercially. 219 These methods indicate that viral culture has significantly underestimated the number of infected individuals. 219 PCR-based methods are now being used routinely in some laboratories for diagnosis. 220 Confocal scanning laser microscopy has been used at the bedside to diagnose infection with herpesvirus. 221

A range of antiviral agents, topical, oral, and intravenous, have been used in the treatment of herpes simplex, both HSV-1 and HSV-2.222.223. and 224. Topical treatment is the usual method, with oral and intravenous therapy reserved for recurrent and persistent lesions, usually in immunocompromised patients. Docosanol 10% cream is an over-the-counter preparation with indirect antiviral activity approved for topical treatment of herpes simplex labialis. Penciclovir 1% cream and acyclovir (aciclovir) 5% ointment are topical antiviral agents that require a prescription in some, but not all countries. A recent randomized clinical study found that acyclovir cream 5% was equally as effective as Compeed® cold sore patch, based on hydrocolloid technology, in the treatment of herpes labialis. 225 Idoxuridine 15% solution, and cidofovir 1% gel can also be used. 161

Systemic medications used include valacyclovir (valaciclovir) and famciclovir, which has improved oral absorption. 161 Foscarnet and cidofovir can be used intravenously for immunocompromised patients with acyclovir-resistant disease.151. and 161. Acyclovir resistance is uncommon in healthy individuals.151. and 226. In patients with AIDS it is 10%. 226 It has a good safety record and is well tolerated by patients. 151 Isotretinoin has also been used in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex. 212

A meta-analysis reported in 2007 confirmed the high clinical efficacy of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir for prophylaxis against recurrent genital herpes infection. 227 Valacyclovir significantly reduces HSV-2 shedding. 228

Experimentally, inhibition of HSV-1 has been produced by a sequence-specific gene-silencing process mediated by small interfering RNA. 229 This is a promising method of gene therapy in the future treatment of a variety of viral diseases.

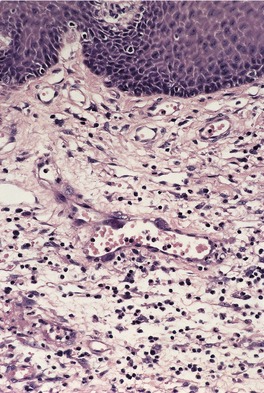

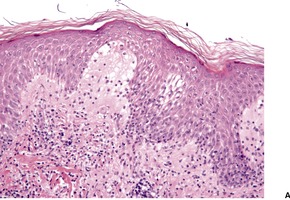

The histological appearances of herpes simplex, varicella, and herpes zoster are very similar. The earliest changes involve the epidermal cell nuclei, which develop peripheral clumping of chromatin and a homogeneous ground-glass appearance, combined with ballooning of the nucleus. 230 Vacuolization is the earliest cytoplasmic alteration. These changes begin focally along the basal layer, but soon involve the entire epidermis. 230 By the time lesions are biopsied there is usually an established intraepidermal vesicle (Fig. 26.9). This results from two types of degenerative change, ballooning degeneration and reticular degeneration. Ballooning degeneration is peculiar to viral vesicles. The affected cells swell and lose their attachment to adjacent cells, thus separating from them (secondary acantholysis). The cytoplasm of these cells becomes homogeneous and intensely eosinophilic, and some are also multinucleate (Tzanck cells). At times the basal layer of the epidermis is also destroyed in this way, leading to the formation of a subepidermal vesicle. The change known as reticular degeneration is characterized by progressive hydropic swelling of epidermal cells, which become large and clear with only fine cytoplasmic strands remaining at the edge of the cells. These eventually rupture, contributing further to the formation of a vesicle. This change is not specific for viral infection and can be seen also in allergic contact dermatitis. Whereas ballooning degeneration is found mainly at the base of the vesicle, reticular degeneration is seen on its superficial aspect and margin.

(A) Herpes simplex. (B) There is an intraepidermal vesicle containing ballooned, acantholytic keratinocytes in which there are intranuclear inclusion bodies. (H & E)

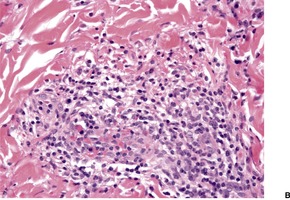

Eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies are found, particularly in ballooned cells (Fig. 26.10). They are more common in multinucleate cells of lesions that have been present for several days. Neutrophils are present within established vesicles. There are also moderate numbers in the underlying dermis, as well as lymphocytes. Neutrophils are prominent in the lesions of herpetic whitlow. Marked inflammation and even vasculitis have been noted in some lesions. 231 As a rule, the dermal inflammation is more severe in herpes simplex than in zoster. Atypical lymphoid cells may be present in the infiltrate where herpes simplex complicates an underlying hematological malignancy. 232 Atypical lymphocytes have been noted in 32 of 45 routine cases of herpes simplex submitted for microscopy. 233 In a study reported from Graz in 2006, atypical lymphocytes were commonly present. 234 Other findings included dense lymphoid infiltrates, angiotropism, and variable numbers of CD30+ and CD56+ cells. Two cases with a pseudolymphomatous appearance revealed a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes by PCR analysis. 234 In another study, CD4+ and/or CD8+ lymphocytes were present in the infiltrate of herpes simplex. 235 The cells expressed both granzyme B and granulysin. 235 In a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a neoplastic infiltrate of cells occurred at the site of a florid herpes simplex infection, but this seemed to be part of a physiological response to the virus. 236

Herpes simplex. The multinucleate keratinocytes have intranuclear inclusion bodies. (H & E)

Uncommonly, erythema multiforme-like changes may be seen in the adjacent skin, concurrent with a vesicle of herpes simplex. A related reaction pattern is so-called ‘lichenoid lymphocytic vasculitis’, a term coined for the changes seen in presumptive cases of herpes simplex with an immunological response (see p. 608). 237 There is an upper dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes, with lichenoid changes in the epidermis and a dermal lymphocytic vasculitis.

Focal involvement of pilosebaceous units is not uncommon in recurrent lesions. 230 In the variant known as herpes folliculitis, 238 pilosebaceous involvement is the dominant lesion (Fig. 26.11). Rarely, the eccrine ducts and glands are involved (herpetic syringitis). 239 Ballooning degeneration may involve cells of the outer root sheath of the deep portion of the follicle. A dermal inflammatory infiltrate is often present in these cases; it is heaviest in the deep reticular dermis – a so-called ‘bottom-heavy’ infiltrate.

Herpes folliculitis. There is a heavy superficial and deep dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes. A necrotic follicle is present in the upper third of the dermis. (H & E)

Dermal nerves in lesional skin in both herpes simplex and herpes zoster show perineural and some intraneural inflammation. Viral antigen can be detected in these inflamed nerve twigs, indicating that they are not just passive conduits for viral spread. 240 Perineural inflammation can also be present in quiescent lesions of herpes labialis. Schwann cell hypertrophy and neuronal necrosis with cytopathic changes may also be present. 240 Sometimes the perineural infiltration is out of proportion to the overlying dermal inflammation.

In late lesions of herpes simplex, ulceration is often present. Ghosts of acantholytic, multinucleate epithelial cells with slate-gray nuclei on routine staining may still be seen in the overlying crust.

Recently, attention has been drawn to the histological appearance of the lesions that recur at the site of previous surgery. These vesicles are subepidermal, with an inflammatory response, complete with multinucleate giant cells, 241 in the uppermost dermis.

A rapid cytological diagnosis of a vesicular lesion can be made by making a smear from the base of a freshly opened vesicle and staining it with the Giemsa stain. The Tzanck test, as this smear is called, is not as sensitive as PCR-based tests. 242 Ballooned cells, some of which are multinucleate, will be seen in herpes simplex, varicella, and zoster. Immunoperoxidase stains specific for HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV are available commercially.

Virus particles of Herpesvirus hominis, measuring between 90 and 130 nm, can be seen in the nuclei of the basal cells. Cells in the malpighian layer often contain other virus-related material, such as nuclear granules and capsules. Viral capsids have also been seen within the nuclei of monocytes, young histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the epidermal vesicles. 243 Large lymphocytes are sometimes seen adjacent to keratinocytes exhibiting lytic changes, suggesting that cell-mediated immunity may be partly responsible for the epidermal damage that occurs. 244

Eczema herpeticum is a generalized infection of the skin with the herpes simplex virus.245.246. and 247. A similar condition (eczema vaccinatum) occurred, in the past, with the vaccinia virus. 248 Both lesions have been grouped together as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption. This condition occurs most commonly in association with atopic dermatitis, 249 but it has also been reported in Darier’s disease,250. and 251. Hailey–Hailey disease, 252 Grover’s disease, 253 pityriasis rubra pilaris, 254 allergic contact dermatitis, 255 pemphigus foliaceus, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, 256 psoriasis,257. and 258. lupus vulgaris, 257 ichthyosiform erythroderma, phenytoin-induced drug rash, 259 a patient receiving facial tacrolimus treatment for atopic dermatitis, 260 and in multiple myeloma, 261 the Sézary syndrome and mycosis fungoides, 262 and following thermal injury. 263 It has also been reported in an HIV-positive patient after laser resurfacing. 264 It has been suggested that interleukin-4, which may be increased in atopic dermatitis, may down-regulate the response against herpes simplex virus and contribute to generalized infection. 265 Reduced numbers of natural killer (NK) cells and a decrease in interleukin-2 receptors probably also contribute. 266

Although eczema herpeticum is characterized by the presence of multinucleate epidermal cells and intranuclear inclusions, rather than the intracytoplasmic inclusions seen in the past with eczema vaccinatum, these features are often obscured by the heavy inflammatory cell infiltrate of neutrophils and early breakdown of the vesicles. Recently formed lesions usually show the typical features of a vesicle of herpes simplex.

Varicella (chickenpox), caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), is a highly contagious disease with an average incubation period of 2 weeks. 267 It is predominantly a disease of childhood. The peak incidence of infection is between 5 and 9 years of age. 268 It is characterized by an acute vesicular eruption; bullous lesions are rare.269. and 270. Postinflammatory scarring of isolated lesions is very common, with a prevalence of just under 20%. 268 The lesions develop in successive crops, so that the rash typically consists of pocks at different stages of development. Thus, papules, vesicles, pustules, crusted lesions, and healing lesions may all be present. Secondary Staphylococcus aureus infections are widely reported. 269 Varicella pneumonia may be seen in adults as a primary infection. Other complications of chickenpox include thrombocytopenia, necrotizing fasciitis, cerebellar ataxia, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, Reye’s syndrome, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and orchitis. 268 In immunocompromised hosts dissemination may occur, or large ulcerated and necrotic lesions (varicella gangrenosa) may develop; chronic verrucous lesions have also been described.271.272. and 273. Atypical recurrent varicella also occurs in patients with hemopathies, 274 and those receiving hemodialysis. 275 An interesting observation is the finding of marked intensification of the varicella eruption in areas of skin which are normally covered but which become sunburnt just before the eruption commences. 276 Photodistributed varicella, mimicking polymorphic light eruption, has been reported. 277 Involvement of the palms and soles is uncommon. 278 Varicella has also been reported largely restricted to an area covered by a plaster cast, 279 and in a patient with Kawasaki disease. 280 It has developed in a patient receiving adalimumab therapy. 281 Viral exanthems, particularly varicella, may localize early and preferentially to areas of prior inflammation. 282

Cutaneous lesions, usually scars, can be seen in neonates with the congenital varicella syndrome. This is a rare syndrome which occurs when a pregnant woman develops varicella before the 24th week of pregnancy. In addition to scars, aplasia cutis, neurological defects, eye abnormalities, and limb hypoplasia may be seen, but less frequently. 283 The incidence of an embryopathy after infection in the first 24 weeks of gestation is estimated at 1–2%. 284

Usually the diagnosis of varicella is made on clinical grounds. In atypical cases, PCR for VZV can be performed. 281

Immunization against the varicella-zoster virus can be carried out using the Oka strain of live, attenuated varicella. Care should be taken to ensure that recipients are not immunocompromised when receiving live vaccines; varicella may result. 285 While the overall benefit of treating uncomplicated cases of varicella in otherwise healthy children has not been considered significant by some clinicians, treatment with oral acyclovir, within 24 hours of the development of the rash, is cost-effective because it allows caregivers to return to work approximately 2 days earlier. 224 Acyclovir does not appear to alter the development of long-term immunity to VZV. 224 The newer antiviral agents have not been extensively studied.

The appearances are virtually indistinguishable from those of herpes simplex, although the degree of inflammation is said to be greater in herpes simplex than in varicella-zoster lesions. 286 Direct immunofluorescence and immunoperoxidase methods, 156 using a monoclonal antibody specific for varicella-zoster virus, 287 and the Tzanck smear are superior to viral culture in the diagnosis of varicella zoster; 288 monoclonal antibody techniques have the advantage of specificity over the Tzanck smear. 287

The chronic verrucous lesions reported in immunocompromised patients show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and massive hyperkeratosis. 271 Herpetic cytopathic changes are also present in keratinocytes.

The ultrastructural features of Herpesvirus varicellae are similar to those of Herpesvirus hominis. However, colloidal gold immunoelectron microscopy using monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between the two. 289

Herpes zoster (shingles) is a common dermatological condition that affects 10–20% of the population during their lifetime, with an increased incidence in the elderly, and in those who are immunocompromised. 290 An estimated 1 million cases of herpes zoster occur each year in the United States. 291 It results from reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. The characteristic rash has a unilateral dermatomal distribution that most often affects the thoracic and lumbar regions, and sometimes the face. Any dermatome can be affected. Rare localizations have included involvement of the penis, 290 the finger, 292 and a recent surgical scar. 293

Herpes zoster is an acute disease that occurs almost exclusively in adults. Childhood herpes zoster is uncommon and usually restricted to immunocompromised children, and those with malignancies.294. and 295. It can develop in immunocompetent children as a consequence of intrauterine VZV infection, or postnatal exposure to this virus at an early age. 296 The illness is febrile and begins with pain in the area innervated by the affected sensory ganglia. The skin in this area becomes red, and papules soon develop. 297 These quickly transform into vesicles and then pustules. There is one report of bullous lesions. 298 Crusts then form and, later, healing takes place. Chronic hyperkeratotic and verrucous lesions may occur in immunocompromised patients.299.300. and 301. Verrucous lesions have been reported in an immunocompetent child who developed chronic varicella-zoster skin infection complicating the congenital varicella syndrome. 283 Chronicity appears to be associated with a particular pattern of viral gene expression with reduced or undetectable levels of the viral envelope glycoproteins gE and gB. 300 Sometimes there is residual scarring, particularly if there has been secondary bacterial infection of the vesicles. Although the virus usually causes a prodrome of pain, pruritus, or a burning sensation, uncommon presentations have included hiccups, 302 eructation, the Ramsay Hunt syndrome, 303 urinary and fecal retention, and sexual dysfunction. 302

Herpes zoster is caused by the same virus as varicella (VZV).304.305. and 306. It occurs in individuals with partial immunity resulting from a prior varicella infection. With few exceptions, zoster appears to represent reactivation of latent virus in sensory ganglia, often in an immunocompromised host. There appears to be an association between herpes zoster and a family history of zoster. 307 The risk increases when multiple blood relatives have been involved. 307 The therapeutic use of arsenic trioxide can lead to reactivation of the VZV. 308 The virus travels through the sensory nerves to reach the skin, where it replicates in the epidermal keratinocytes. Viremia may occur but it is not consistent. 309 Now that a vaccine is available, it is hoped that this may lessen the incidence of herpes zoster in the future. 310 Nevertheless, herpes zoster has been reported in a child following immunization for varicella using the Oka strain of live, attenuated varicella. This strain was recovered from lesional skin. 311

Zoster is not highly infectious, although this has been recently disputed. 312 When children are infected by adults suffering from zoster they develop varicella and not zoster. An attack of either disease leaves the patient with some measure of immunity against both. Recurrent attacks of zoster are most uncommon. 304 Many cases diagnosed as recurrent herpes zoster are probably recurrent herpes simplex.313. and 314. Herpes simplex virus has been detected by PCR in two cases with a persistent, painful papular eruption in a zosteriform pattern. 315 Conversely, there is also evidence from PCR studies that initial herpes zoster is sometimes misdiagnosed as herpes simplex. 316 Simultaneous varicella zoster and herpes simplex infection also occurs, even in immunocompetent individuals. 317 PCR is the method of choice for the early diagnosis of herpes zoster. 318 Disseminated herpes zoster with visceral involvement is a rare complication of AIDS and other immunocompromised states.306.319.320. and 321. It has also been reported in idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia. 322

Herpes zoster scars are prone to the occurrence of Wolf’s isotopic response, which describes the development of a new skin disorder at the site of another unrelated and already healed skin disease. The diseases reported in healing/healed lesions of herpes zoster include granuloma annulare, 323 granulomatous dermatitis, 324 comedones,325. and 326. lichen planus, 327 giant cell lichenoid dermatitis, 328 urticaria, 329 granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, rosacea, 330 sarcoidosis, 331 lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, morphea, an eosinophilic dermatosis, fungal infections, 332 pseudolymphoma, 333 lymphoma, 334 leukemia cutis, 335 Rosai–Dorfman disease, Kaposi’s sarcoma, various skin cancers, and metastases.336. and 337. Necrotizing fasciitis is another rare complication of disseminated cutaneous herpes zoster. 338 VZV has been inconsistently identified in some of these post-herpetic inflammatory reactions. Virus was identified in a patient with cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia and concomitant folliculitis and vasculitis. 339

Post-herpetic neuralgia is a serious complication. 340 It can cause debilitating pain and impaired quality of life. 291 Rash severity appears to correlate with prolonged post-herpetic neuralgia; 341 it is also more prevalent in patients over 50 years of age. 342 Severe ocular damage may result when the ophthalmic division of a trigeminal nerve is involved. 343 If multiple dermatomes are involved, they are usually contiguous. There is one report of an immunocompromised patient in whom seven disparate dermatomes were involved (zoster multiplex). 344

The host’s immune response to viral skin infections is a complex one combining the effects of natural killer (NK) cells, interferons (IFN), and macrophages which restrict viral replication and spread. 345 Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are also involved. For their part, the viruses produce substances that allow them to escape, in part, the host’s immune recognition. 345 This is a complex process involving down-regulation of both MHC-I and MHC-II pathways. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression on the surface of keratinocytes allows binding to occur with a certain class of T cells (LFA-1 ligand-bearing T cells) involved in the host’s response to viruses. It has now been found that ICAM-1 expression is lost on VZV-infected keratinocytes, reducing their capacity to bind with these T cells, suggesting a further immune-evasion strategy by the virus. 345

The treatment of herpes zoster involves the use of antiviral drugs, or combination regimens using these drugs with corticosteroids to reduce the severity and/or duration of the disease, and the use of other strategies to decrease the pain of any post-herpetic neuralgia that may develop. 346 In this latter category are opioids, anticonvulsants such as gabapentin, tricyclic antidepressants, capsaicin cream, and lidocaine patches 5%.

Acyclovir had been the drug of choice for many years, but now the newer drugs famciclovir and valacyclovir are preferred because of their superior pharmacokinetic characteristics and simpler dosing regimens. 342 Antiviral therapy should be commenced within 72 hours of the onset of the rash, although therapy initiated after this time appears to be still helpful. In a meta-analysis involving 691 patients, acyclovir was found to reduce zoster-related pain duration and prevalence by about half. 342 Similar studies with the newer antiviral agents have not yet appeared. PCR can be used to detect mutations or deletions in the thymidine kinase gene in herpes simplex and VZV which confers on the viruses a resistance to acyclovir. 347

Administration of gabapentin in conjunction with antivirals during the acute phase of zoster may offer further protection against post-herpetic neuralgia. 342 The addition of corticosteroid may, in the short term, reduce herpes-related pain intensity, but it is associated with a risk of serious adverse effects. Antiviral therapy is essential in patients presenting with herpes zoster ophthalmicus, and in patients who are immunocompromised. 342

The prevention of herpes zoster involves the use of vaccination. In 2006, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of a live attenuated preparation of the Oka/Merck strain of VZV for clinical use. Its potency is said to be 14 times that of the varicella vaccine that preceded it.348. and 349. It boosts the recipient’s immunity to VZV, reducing the chance that the individual’s latent VZV will reactivate producing zoster. 346 It reduces the incidence of zoster by 50%, and in those who still contract the disease, it reduces the rate of post-herpetic neuralgia by 66%. 348 Its cost will be of concern in some countries.

The appearances resemble those described for herpes simplex. Despite the comment made earlier that lesions of herpes simplex are usually more inflammatory than those due to varicella-zoster infection, 286 dermal inflammation may be prominent in some cases of herpes zoster, and there may occasionally be a vasculitis. 350 If the vasculitis is severe, necrotizing lesions will be present. 351 A granulomatous vasculitis and lesions resembling granuloma annulare may be seen in healing or healed lesions.323.352. and 353. These factors, as well as secondary infection, contribute to the scarring which sometimes ensues.

Eccrine duct and secretory coil involvement has been reported, but it is quite uncommon. 354 Concomitant epidermal involvement is not always present in these cases. 355 Folliculosebaceous involvement is more common. It is thought that exclusive folliculosebaceous involvement, in the setting of a non-vesicular eruption (that is, without initial epidermal involvement) represents early herpes zoster. 356 This is probably a consequence of the virus traveling via myelinated nerves to the skin that terminate at the isthmus of the hair follicles, in contrast to recurrent herpes simplex in which transport of the virus is to the epidermis, via terminal non-myelinated nerve twigs. 356

The chronic verrucous lesions show hyperkeratosis, verruciform acanthosis, and virus-induced cytopathic changes. 300

The term ‘herpes incognito’ has been used for the cases in which the typical multinucleated cells are not encountered in routine sections. 357 Such cases usually show a lichenoid lymphocytic vasculitis, often with subepidermal edema, and often with a periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate with variable sebaceitis. 357 Deeper levels in such cases will often show more typical features.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) belongs to the subgroup of β-herpesviruses. Like other members of the family Herpesviridae, this virus produces primary infection, latent infection, and reinfection; 358 however, its site of latency is not known.

There are few reports of cutaneous involvement with CMV.359.360. and 361. A maculopapular eruption is the most common clinical presentation, and is seen most often in patients with CMV infection who are treated with ampicillin. This is analogous to the situation in infectious mononucleosis. 360 Urticaria, 362 vesiculobullous lesions, 363 pustular lesions, 364 ulceration,365. and 366. including genital ulcers, 367 keratotic lesions, 368 diaper dermatitis, 369 and even epidermolysis have been reported. Cytomegalovirus was demonstrated in the dermis in a patient with pityriasis lichenoides (PLEVA). 370 Its etiological role was uncertain. Magro et al have reported seven adults who developed a cutaneous vasculopathy or sclerodermoid changes in temporal association with recent CMV infection. 371 No CMV inclusion bodies were present. 371 Often the clinical picture is quite non-specific.372. and 373. The patients are usually immunocompromised,363.374. and 375. a clinical setting in which mixed infections with other agents, particularly herpes simplex virus, may occur.358.376.377.378.379.380. and 381. Patients with chronic renal failure are also prone to infection. 382

Infants with congenital infection with CMV may present with petechiae and blue-red macular or plaque-like (so-called ‘blueberry muffin’) lesions, in addition to neurological abnormalities. 383 Perineal ulcers were present in one infant. 384 The lesions resolved without specific therapy.

Ganciclovir, a guanosine analogue that selectively inhibits CMV DNA polymerase, can be used to treat infections. 384 Foscarnet and valganciclovir have also been used. 385 There is still a high mortality in patients with disseminated disease, but when there is local cutaneous infection in skin wounds, the prognosis is usually good. 382

There is usually a non-specific dermal infiltrate. The characteristic changes are enlarged endothelial cells in small dermal vessels (Fig. 26.12). 360 The nuclei of these cells contain large eosinophilic inclusions, surrounded by a clear halo. Cytomegalic changes in the absence of nuclear inclusions have been reported. 386 There may also be prominent neutrophilic infiltration of the involved vessel walls, although an unequivocal leukocytoclastic vasculitis is quite rare. 387 Other cells that may harbor viral inclusions include fibrocytes and macrophages. Ductal epithelial cells are rarely involved. 388 The ‘blueberry muffin’ lesions associated with congenital infections are the result of dermal erythropoiesis. 383 They may also be seen in congenital rubella infections. 383

Cytomegalovirus infection. A blood vessel in the dermis contains several enlarged endothelial cells, each containing an inclusion body. (H & E) (Photomicrograph kindly supplied by Dr G Strutton)

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was discovered in 1964 in African Burkitt lymphoma-cell cultures. 391 It belongs to the human γ-herpesvirus subfamily along with human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). It is best known as the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis, following which it establishes a clinically silent lifelong infection. It also causes a range of natural killer (NK)-cell malignancies as well as B- and T-cell lymphomas, and a hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (see p. 985), which is often fatal. Carcinomas and leiomyosarcomas may also result from EBV infection. Many of these tumors are found predominantly in southeast Asia and Japan. They were reviewed recently.391. and 392.

A cutaneous rash is seen in approximately 10% of patients with infectious mononucleosis, but this incidence increases dramatically if ampicillin is administered to the patient. It also occurs when ampicillin is used in patients with EBV reactivation. 393 The rash is usually erythematous, macular, or maculopapular. Erythema multiforme and urticaria may occur. 1 Rare cutaneous manifestations of EBV infection include a granuloma annulare-like eruption, 394 the Gianotti–Crosti syndrome, 395 painful genital ulcers,396. and 397. oral hairy leukoplakia, and lymphoproliferative lesions in immunocompromised patients, particularly following transplantation. 398 Although the lesions may histologically mimic malignant lymphoma, the lesions disappear completely in some patients after the degree of immunosuppression is lowered.398.399. and 400. Epstein–Barr virus has also been implicated in the etiology of Kikuchi’s disease,401. and 402. and in a natural killer (NK) cell lymphocytosis associated with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites. 403

Extreme sensitivity to infection with EBV is seen in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome (XLP1 – OMIM 308240), caused by a mutation in the SHD2D1A gene encoding SLAM-associated protein located at Xq25.404. and 405. A small number of cases (XLP2 – OMIM 300635) are caused by mutations in the gene encoding the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP/BIRC4), which maps to the same region as the gene for XLP1. 404 Both diseases have a similar phenotype with acquired hypogammaglobulinemia and a malignant lymphohistiocytosis. Early transplantation of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells is the only means available to prevent fatal EBV complications later in life. Similar cases, in which no genetic abnormality has been detected, are sometimes seen. 406

In-situ hybridization for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA (EBER) remains the gold standard for virus detection in tissue samples. 391

Both oral and intravenous acyclovir have shown little or no clinical benefit in the treatment of uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis. 224 Acyclovir, ganciclovir, penciclovir, famciclovir, foscarnet, zidovudine, and interferon have all been shown to have in-vitro efficacy against the replication of EBV. 224

There is usually a mild perivascular infiltrate of inflammatory cells. The changes are non-specific.

Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) is the sixth member of the family Herpesviridae to be identified. It shows closest homology with cytomegalovirus and HHV-7. 407 It is a member of the β-herpesvirus subfamily. Most of the reports of this infection are in the pediatric literature. The virus produces a cutaneous eruption (exanthem subitum) resembling measles or rubella in infants. 408 The illness may be accompanied by fever. Like other herpesviruses, after the primary infection, it establishes latency in different cells and organs. 409

HHV-6 infection in infants is said to be the commonest cause of fever-induced seizures.407. and 410. In adults, infection is seen primarily in immunocompromised individuals. Its reactivation may be involved in the pathogenesis of the rash and GVHD that may follow allogeneic stem cell transplantation. 411 Herpes simplex virus (HSV) may also be reactivated in these circumstances. 182 Although HHV-6 may play a role in multiple sclerosis and a demyelinating disease in patients with HIV infection, it plays no role in the etiology of lymphomatoid papulosis. 410 Although parvovirus B19 is usually implicated in the etiology of papular-purpuric ‘gloves-and-socks’ syndrome (see p. 626), a case has been reported in association with HHV-6 infection. 412 The Gianotti–Crosti syndrome may also be produced by HHV-6 infection. 413

There are now many reports of a drug hypersensitivity syndrome occurring in association with reactivation of HHV-6.414.415. and 416. This has been called the drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). 417 It is considered further in Chapter 20, p. 515. In one case a fulminant hemophagocytic syndrome developed418 and in another toxic epidermal necrolysis. 409 HHV-7 may also act in concert with HHV-6 in producing the drug hypersensitivity syndrome. 415 CMV and/or EBV have also been implicated. 419 Their reactivation occurs in a similar sequential order to that seen in GVHD. 420 The drugs initially implicated were sulfasalazine, 414 allopurinol, 415 and phenobarbital. 418 Many other drugs have since been implicated (see p. 515). There is some controversy regarding the role of HHV-6 and HHV-7 in the etiology of pityriasis rosea (see p. 100). 421 It is possible that viral reactivation is the explanation for its detection in a number of circumstances. 422

The cutaneous lesions of exanthem subitum are characterized by spongiosis, small spongiotic vesicles and exocytosis of lymphocytes, sometimes producing Pautrier-like lesions. There is often edema of the papillary dermis and a superficial perivascular infiltrate of mononuclear cells. 408 Cytopathic changes, resembling those seen in herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections, are absent.

Human herpesvirus-7 (HHV-7) was first isolated from a peripheral blood T cell in 1990, and isolated again in 1992 from a patient with chronic fatigue syndrome. 410 HHV-7 can provide a transactivating function for HHV-6. HHV-7 is ubiquitous and infects more than 80% of children in infancy. 410 It has been implicated in the etiology of pityriasis rosea (see p. 100), but reactivation of the virus is a possible explanation for its occurrence in some cases. There is no clear link between HHV-7 and any specific disease at this time. 423

Unlike the other recently described herpesviruses (HHV-6 and HHV-7), this virus (HHV-8) does not appear to be ubiquitous. 424 Its role in the etiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive individuals was confirmed in 1994 when unique DNA sequences were isolated from biopsies of Kaposi’s sarcoma. The virus, initially called Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), was subsequently renamed HHV-8. Sequence analysis confirms that it is related to Herpesvirus saimiri, which induces lymphoid malignancies in some primates, and to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). 425 It is a member of the γ-herpesvirus subfamily along with these two viruses. 426

The role of HHV-8 in the etiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients infected with HIV is now beyond doubt.427.428. and 429. It has also been found in a variable but significant number of HIV-negative cases. 430 The viral load of HHV-8 is relatively low in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative cases. 431 HHV-8 infects the endothelial-derived spindle cells of Kaposi’s sarcoma as well as CD19+ B cells. This latter event may be etiologically significant in the causation of some cases of Castleman’s disease (see p. 946) and primary effusion lymphoma. 432 It has also been found in lymphomas and in other lymphoproliferative disorders with heterogeneous presentations. 433 This subject has been reviewed recently.432. and 433. Its presence in a surprising number of skin cancers, and in lesions of pemphigus has not been satisfactorily explained, although tropism for lesional skin has been postulated.434.435. and 436. Other studies have failed to confirm these findings.437. and 438. It is not associated with pityriasis rosea. 439

Papovaviruses (papillomaviruses) are DNA viruses which replicate in the nucleus. The only important virus in this group in dermatopathology is the human papillomavirus (HPV), which produces various types of warts on different parts of the skin.441.442.443.444. and 445. The use of new techniques, such as DNA hybridization, has allowed the separation of over 120 antigenically distinct strains of HPV.446. and 447. Further genotypes have been identified, but not fully characterized. 448 PCR is now used routinely for the typing of HPV. 347 In recent years attempts have been made to relate specific antigenic strains of HPV to particular clinicopathological groups of verrucae.449. and 450. Some strains have oncogenic potential, and the theoretical mechanisms by which HPV may cause cancer have been reviewed, 451 as has the role of the various immune defense mechanisms to these oncogenic and other strains of HPV.452. and 453. The following correlations have been recorded: HPV-1 – plantar warts,454. and 455. but also common warts and anogenital warts; HPV-2 – common warts, but also plantar, 454 oral, 456 and anogenital lesions; HPV-3 – plane warts and epidermodysplasia verruciformis; HPV-3 (variant) – common warts; 457 HPV-4 – plantar and common warts; HPV-5 – epidermodysplasia, which in cases associated with this strain of HPV is usually complicated by carcinoma; HPV-6 – anogenital warts and also epidermodysplasia; HPV-7 – warts in meat and fish handlers;458.459.460.461. and 462. HPV-8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 17, 19, 22, 24, and many others – epidermodysplasia; HPV-11 – anogenital lesions; 463 HPV-13 and 32 – focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease);464. and 465. HPV-57 – plantar epidermoid cysts and nail dystrophy, cutaneous verrucae;466.467. and 468. HPV-60 – plantar warts and epidermal cysts, and papular and nodular lesions on the extremities;469. and 470. HPV-63, 65, and 66 – plantar warts; 471 and HPV-75, 76, and 77 – common warts in immunosuppressed patients. 448 HPV-63 appears to have an eccrine-centered distribution in plantar skin. 471 There is now great interest in the role of HPV-16 and 18 in the etiology of uterine cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive carcinoma of the cervix. HPV-16 is also the strain most frequently implicated in the etiology of bowenoid papulosis, a disease which sometimes progresses to invasive carcinoma. HPV-16 has also been detected in anogenital warts, 472 and in a squamous cell carcinoma of the finger. 473 Various HPV strains may be present in immunosuppressed patients474 and in skin tumors removed from them.475.476.477. and 478. They may also be found in the skin tumors of immunocompetent individuals. 479 Individuals whose immunosuppression results from HIV infection have an increased prevalence of HPV infections, a more rapid progression of the disease, and a higher number of invasive carcinomas. 480 Recent studies have detected HPV strains usually associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis in some of the malignant and premalignant skin lesions of renal transplant recipients.481. and 482. This was not found in an earlier study. 483 Furthermore, HPV-5 has recently been found in psoriatic skin lesions, but it is not known if it has any etiological role (see below).

The traditional classification of verrucae will be used here:

• verruca vulgaris or common wart

• palmoplantar warts, including superficial and deep types

• verruca plana

• epidermodysplasia verruciformis

• condyloma acuminatum.

It should be noted that there is some clinical and histological overlap between these groups. 484 Focal epithelial hyperplasia and bowenoid papulosis will also be discussed.

The common wart (verruca vulgaris) occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, although adults are also frequently infected. 485 Warts have been found in approximately 20% of school students. 486 The lesions may be solitary or multiple, and they are usually found on exposed parts, most frequently on the fingers. 487 Uncommonly, verruca vulgaris occurs on covered areas, such as axillae, groins, or genital areas. 488 They are hard, rough-surfaced papules that range in diameter from about 0.2 cm to as much as 2 cm. New warts may form at sites of trauma (Koebner phenomenon), though not so frequently as in cases of plane warts. They are preferentially associated with HPV-2, but may be induced by HPV-1, HPV-4, HPV-27, and uncommonly, HPV-7.464. and 489. HPV-57 has been reported to produce multiple, sometimes recalcitrant cutaneous verrucae; 468 it is not uncommon in patients with HIV infection. 490 In children, HPV-6 and/or 11 are rarely found in common warts, 491 while HPV-75, 76, and 77 have been identified in lesions from immunosuppressed patients of all ages. 448 Disseminated HPV-11 infection has also been reported in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris receiving various treatments. 492 Extensive verrucae have been reported in immunodeficiency syndromes, including CD4+ T-cell lymphocytopenia.493.494.495. and 496. They may clear following the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).497. and 498.

While the great majority of genital warts in adults are due to HPV-6 and HPV-11, this is not so in young girls in whom the occurrence of these strains raises the question of sexual abuse. In one study of 29 genital warts in girls less than 5 years of age, 41% were due to HPV-2 and the remainder to HPV-6/11. 499 Lesions positive for HPV-2 often show the marked hyperkeratosis typical of verruca vulgaris in other sites. 499

An interesting observation of uncertain significance is the finding that the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is expressed by keratinocytes in verruca vulgaris and also condyloma acuminatum. 500