Vertical Scar Breast Reduction and Mastopexy Without Undermining

Claude Lassus

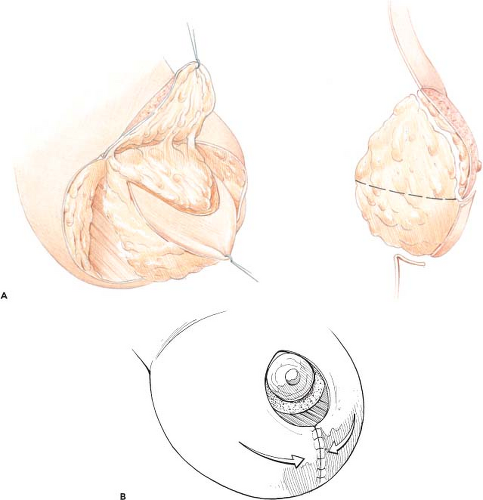

In 1964, I performed a breast reduction on a patient with unilateral breast hypertrophy (Fig. 86.1) using a procedure that combined four principles (Fig. 86.2):

A central vertical wedge resection to reduce the size of the breast

Transposition of the areola on a superiorly based flap

No undermining

A vertical scar to finish off

I first published this technique in 1969 and then again in 1970. More than 40 years after this first operation, I am still using vertical mammaplasty, even though some modifications have been made to avoid the vertical scar appearing below the inframammary fold.

Why the Vertical Mammaplasty?

For many years, most of the candidates for breast reduction were only concerned with the diminution of the size of their breasts. This was also the main concern for plastic surgeons, who did not give much thought to scarring. However, more recently, candidates for this operation have been demanding better results.

Most important, they want beautiful breasts. What is a beautiful breast? What is considered beautiful is certainly different in Europe than in North and South America, Asia, and Africa. In France, a breast is considered beautiful if it has a good size with fullness in the upper part, good projection, and good position of the nipple (Fig. 86.3). Patients want their results to last over the years. They also want a safe procedure with minimal scarring.

In France, the results of a recent poll showed that 78% of patients are anxious about the complications of any aesthetic operation. It is obvious that we must always use safe procedures, particularly in mammaplasty because the breast is so important to women.

Is Vertical Mammaplasty A Safe Procedure?

Neither the surgeon nor the patient likes to see bleeding, infection, skin necrosis, glandular necrosis, nipple loss, or loss of nipple sensation after reduction mammaplasty. One of the principles of the operation is to reduce the size of the breast through a central wedge “en bloc” resection at the lower part of the breast (skin, fat, and gland) and only fat and gland beneath the areolar flap (Fig. 86.2A). When this resection has been achieved, the breast cone is reconstructed by drawing centrally each lateral part of the amputated breast (Fig. 86.2B). Because no undermining has been performed (the skin is not elevated from the gland, and the gland is not separated from the muscle), at the end of the operation no dead space is present in the breast. So, if accurate hemostasis has been achieved, no hematoma will be seen in the postoperative course. Drains are unnecessary (Fig. 86.4).

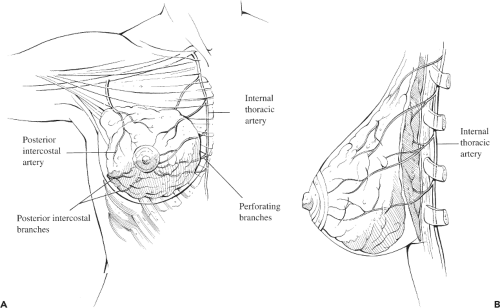

The central vertical wedge resection does not impair the blood supply to the gland or to the skin (Fig. 86.5). Moreover, because the gland has not been separated from the muscle, the flow of blood through the perforators remains undisturbed. With a vertical mammaplasty, there should be no skin necrosis or glandular necrosis.

An important principle of mammaplasty is the safe transposition of the nipple-areola complex. Since 1964, I have generally used a superiorly based pedicle. Why? If we look at the three main possible patterns of blood distribution to this anatomic complex as described by Marcus in 1934 (Fig. 86.6), it is clear that the superior pedicle flap does not impair any of these different patterns. That explains why this flap is safe. However, when the nipple-areola complex has to be moved too high (greater than 10 cm), the pedicle is folded back on itself so much so that the venous blood return can be disturbed and an areolar necrosis may occur. In such instances, I use a lateral flap as advocated by Skoog in 1963 or a medial dermoglandular flap such as the one I have described (Fig. 86.7).

The nipple is innervated from many sources, not just from the anterior branch of the fourth lateral intercostal nerve. The superiorly based flap preserves most of the sources, and because the skin has not been separated from the gland, the anterior branch of the fourth lateral intercostal nerve is also preserved (Fig. 86.8). Nipple sensation is rarely disturbed after a vertical mammaplasty.

My vertical mammaplasty produces excellent long-lasting results. Large breasts can be reduced through a horizontal amputation, a vertical amputation, or a combination of these types of resection. It is well known that a horizontal amputation produces a flat breast (Fig. 86.9). In contrast, a vertical amputation gives projection to the breast. When the central wedge resection has been performed as previously described, the breast cone is reconstructed by joining the lateral parts of the amputated breast. This maneuver moves the remaining breast tissues upward and forward, as does the pinching of the inferior pole with the fingers. Vertical mammaplasty employing a vertical amputation yields the same result (i.e., a nice projection and fullness at the upper pole) (Figs. 86.10 to 86.12).

When the central wedge resection is performed, most of the pendulous portion of the breast is removed (Fig. 86.13). To reconstruct the breast cone, the lateral portions of the amputated breast are drawn centrally toward each other; however, because these lateral parts are not ptotic, there is no need to anchor them in a higher position by suturing them to the muscle. This

makes the results longer lasting. Avoiding undermining also helps.

makes the results longer lasting. Avoiding undermining also helps.

The Vertical Scar Is Not the Minimal Scar That Can Be Left After A Mammaplasty

Although a periareolar scar is the shortest possible scar, my experience is that in average or large hypertrophies the vertical scar is the shortest scar that is practical. This type of scar has several advantages. It is barely visible in the standing position, it usually vanishes over the years, and it rarely becomes hypertrophic, even in women with darker skin.

Many surgeons have long said that the vertical scar should not exceed 5.5 cm in length at the end of surgery. Why? If we measure the distance between the inferior border of the areola and the inframammary fold in a variety of different breasts that are considered beautiful, we see that this distance is variable according to the size of the breast. It ranges from 4.5 to 10 cm or even more. Therefore, the appropriate length of the vertical scar is not fixed. The only important point is that at the end of the operation the inferior extremity of the vertical scar must be situated above the existing submammary fold. If the scar is positioned above or at the limit of this fold, its inferior part will not show afterward.

The vertical mammaplasty, as I perform it, allows a significant reduction of breast volume, but this does not mean converting extremely large breasts into very small ones. Vertical mammaplasty can only reduce about 50% of the existing volume.

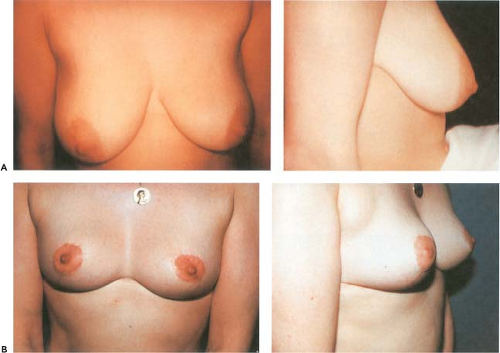

Careful patient selection with this procedure is crucial. A good choice is a young woman with good elastic skin and a firm, glandular breast, not too big and not too ptotic (Fig. 86.14). After having performed several operations of this type, the surgeon can progressively extend its indications (Fig. 86.15).

I do not believe it is possible to draw exact preoperative markings for a reduction mammaplasty, just as it is impossible to draw out the plan in a rhinoplasty or a face lift. Why should it then be possible in breast reduction? To me, surgery of the breast is just like rhinoplasty, that is, sculpture. The surgeon is working in three dimensions and must have an artistic feeling to achieve beautiful breasts. A sculptor needs landmarks to achieve his or her work; the surgeon also needs landmarks to accomplish a vertical mammaplasty.

Point A is no longer the new nipple position. It marks the new position of the upper border of the areola. I do it as shown in Figure 86.16: I measure the acromion–olecranon distance. I take the midpoint of this distance and another point located 2 cm below. From this last point, I draw a horizontal line that

crosses a vertical line coming from the nipple; at the intersection of these two lines is point A.

crosses a vertical line coming from the nipple; at the intersection of these two lines is point A.

Figure 86.6. The block of resection does not impair the blood supply to the remaining gland and skin. |

Figure 86.7. A: Drawing of the lateral flap. B: The flap has been raised. C: One side completed. D: Drawing of the medial flap. E: The flap has been raised. F: Thickness of the flap. |

Figure 86.10. The vertical mammaplasty achieves fullness at the upper pole and projection to the breast, as does the pinching of the inferior pole with the fingers. |

The second key point is point B, located above the crossing of the inframammary fold with the vertical line coming from the nipple (Fig. 86.17): It is at 3 cm in small hypertrophies and ptosis; at 4.5 cm in average cases; and at 6 to 9 and even 10 cm in very large hypertrophic ptotic breasts. The estimated amount of resection is then determined. By pushing the breast medially and then laterally, one joins A and B (Fig. 86.18). This area may also be determined by pinching the breast with the fingers. Two points are then marked where the fingers touch each other, and then A and B are joined through these two points. Figure 86.19 shows the approximate area of resection and how the superior flap is drawn.

Figure 86.14. A good candidate to begin with the vertical mammaplasty: good elastic skin, firm, glandular breast, and moderate hypertrophic ptotic skin. |

Figure 86.15. After the surgeon has performed several operations, he or she can consider more indications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|