Vertical Reduction Mammaplasty

Elizabeth J. Hall-Findlay

The key to a good breast reduction is in combining an aesthetic sense of an ideal breast with an understanding of the anatomy and science of tissue healing. Each surgeon must adapt different designs to different patient presentations. No single technique is applied to all breasts.

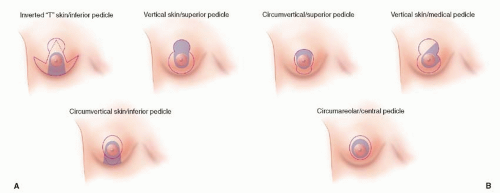

The term “vertical” is misleading because it only applies to the final scars. Confusion is generated by equating the choice of the skin resection pattern with the choice of pedicle used to transfer the nipple-areolar complex. Different pedicles can be combined with different parenchymal resection patterns and both can be combined with different skin resection patterns.

Because the vertical skin resection pattern is often associated with a superior or superomedial pedicle and because the inverted-T skin resection pattern tends to be associated with an inferior or central pedicle, the terms are often used without clear distinction. This chapter outlines how to design and perform a medial or superomedial pedicle with a Wise parenchymal resection pattern and a vertical skin closure.

Although some skin types can be effective as a skin brassiere, skin expansion techniques have taught us that skin and dermis stretch when tension is applied. The approach described in this chapter does not rely on skin to hold the breast shape. The concept of the inferior vertical wedge resection combined with a tension-free parenchymal closure and a tension-free skin closure will result in good healing and an enduring breast shape.

ANATOMY

The breast is a subcutaneous structure that originates at the fourth interspace. It is attached to the skin at the nipple and is only loosely connected to the pectoralis fascia. The breast is held in place by two zones of adherence: 1) the skin-fascial attachments at the inframammary fold (IMF) and 2) The skin-fascial attachments over the sternum (akin to the gluteal crease and the sacral skin attachments). The breast is not “attached” to the pectoralis fascia. The lateral and superior breast borders are relatively mobile while the inferior and medial borders are held in place by skin adherence to deep fascia.

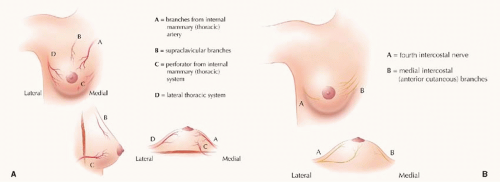

Blood Supply

There is a deep artery (with venae comitantes) that emanates from the fourth branch of the internal mammary artery and perforates through the intercostals and the pectoralis muscle and enters the breast just medial to breast meridian above the fifth rib (Figure 56.1A). This is the main blood supply to an inferior pedicle (and the inferior flap used in a mastopexy). As pointed out by Ian Taylor, the rest of the breast blood supply is superficial. This makes sense as one envisions breast growth from a small subcutaneous fourth interspace structure which has a deep artery and vein. As it grows and develops, the breast pushes the arteries and veins contained in the subcutaneous tissue outward.

The main vascular supply of the breast (both deep and superficial) originates from the internal mammary system. The veins and arteries in the superficial system do not travel together. The veins are located just beneath the dermis and they tend to drain superomedially. They can often be seen through the skin. The arteries start out from a deep level at the periphery of the breast and then travel in the subcutaneous fat.

Because the arteries are superficial around the curve of the breast, the design of the pedicle for the nipple-areolar complex can be dermal rather than dermoglandular, but care must be taken to preserve the deep tissue around the periphery of the breast. Because the veins lie just under the dermis, it is important to maintain a dermal connection to most pedicles.

The artery to a superior pedicle originates at the second interspace. It travels laterally and is the same vessel that supplies a deltopectoral flap. There is a large descending branch, which curves over the breast and enters the areola about 1 cm deep to the skin and close to the breast meridian.

The artery to a medial pedicle originates at the third interspace and curves up over the breast in the subcutaneous tissue. A true superomedial pedicle will contain both the artery to a superior pedicle and the artery to a medial pedicle. This is also an ideal pedicle because most of the venous drainage is superomedial. The vessels are superficial at the level of the areola but deep close to the sternum.

The artery to a lateral pedicle comes from the superficial branch of the lateral thoracic artery. It can enter the breast at a fairly low level and a lateral pedicle should be designed with a low base to ensure that the artery is included. This artery is also deep at the periphery of the breast but becomes more superficial closer to the areola. The arteries to both a superior and a lateral pedicle can be easily located with a Doppler.

The deep artery and vein from the fourth interspace supply an inferior or central pedicle. There are vessels that curve around the inferior aspect of the breast from the fifth (and possibly sixth) interspace and enter the breast at the level of the IMF. They have a deep origin and curve around to enter the breast in the superficial subcutaneous tissue.

Nerve Supply

Innervation to the nipple-areolar complex is said to be provided by the lateral branch of the fourth intercostal nerve (Figure 56.1B). Although this is true, it does not constitute the only nerve supply. The lateral branch divides into both a superficial branch and a deep branch that supply the nipple and areola. The superficial branch is carried in a lateral pedicle. The deep branch travels along the surface of the pectoralis fascia and then turns upward toward the nipple at the breast meridian. This is interesting because it means that any full-thickness pedicle should be able to incorporate this deep branch. There are also medial branches of the intercostal system that run superficially and supply innervation to a medial pedicle. Supraclavicular branches run superficially and supply a superior pedicle.

A study by the author of over 700 breast reduction patients who had either a full year follow-up or who had already achieved full sensation were assessed. There were 58 breasts with superior pedicles, 147 breasts with lateral pedicles, and 1,206 breasts with medial pedicles. Patients were asked to compare their preoperative and postoperative sensation on a visual analog scale. Sixty-seven percent of superior pedicles, 77% of lateral pedicles, and 85% of medial pedicles recovered normal to near-normal sensitivity.

Ductal Preservation

There are approximately 20 to 25 ducts that enter the nipple. Each duct is fed by glandular breast parenchyma. Although dermal pedicles may preserve arterial, venous, and nerve supply, it is unlikely that dermal pedicles will retain much breast

feeding potential. Ducts may reconnect to some degree but dermoglandular pedicles will preserve more connections to glandular and ductal tissues. There is a good study by Norma Cruz-Korchin that shows no difference in breast feeding in large-breasted patients with or without breast reduction.

feeding potential. Ducts may reconnect to some degree but dermoglandular pedicles will preserve more connections to glandular and ductal tissues. There is a good study by Norma Cruz-Korchin that shows no difference in breast feeding in large-breasted patients with or without breast reduction.

DESIGN

There has been considerable reluctance to adopt the vertical skin resection patterns in breast reduction surgery (Figure 56.2). This is based on a fear that the shape takes a long time to finalize and that there is a higher revision rate due to inframammary bunching. Neither is true.

The key is to leave a Wise pattern of parenchyma behind and to close both the pillars and the skin without tension. It makes more sense to remove the heavy inferior pole than it does to remove the upper pole. The inverted-T patterns tend to use the skin brassiere to hold the breast shape. Placing the skin repair under tension inevitably leads to wound healing problems. On the other hand, the vertical patterns tend to use the breast parenchyma to provide and maintain the shape.

Most inverted-T-type breast reduction patterns remove a horizontal ellipse of skin and breast tissue and involve chasing dog-ears medially and laterally. Most vertical-type breast reduction patterns remove a vertical ellipse of skin and breast tissue and involve chasing dog-ears superiorly and inferiorly. Lateral and medial dog-ears can sometimes be difficult to prevent and treat and the horizontal resection sometimes leaves a boxy breast shape with a wide base.

The vertical wedge resection allows better narrowing of the breast base and increases breast projection, while the horizontal approaches tend to flatten the breast. To prevent pseudoptosis in the inverted-“T” approach, the vertical skin length from nipple to IMF is restricted to about 5 cm. Although some coning of the breast tissue occurs with the inverted-T patterns, the nature of the resection plays a minor role in shaping. The increased length of the vertical scar is needed to accommodate the increased projection that results from the vertical wedge resection approach.

The choice of pedicle will also influence the resultant breast shape. The superior, superolateral, and superomedial pedicles will rely less on the skin brassiere to hold the shape. The inferior pedicle may give way to gravitational forces. The choice of pedicle will influence the parenchymal resection pattern. Any type of skin resection pattern can, however, be used with any type of pedicle. A “J,” “L,” or small or large “T” can be added to remove any excess loose skin if needed.

VERTICAL BREAST REDUCTION USING THE MEDIAL OR SUPEROMEDIALLY BASED PEDICLE

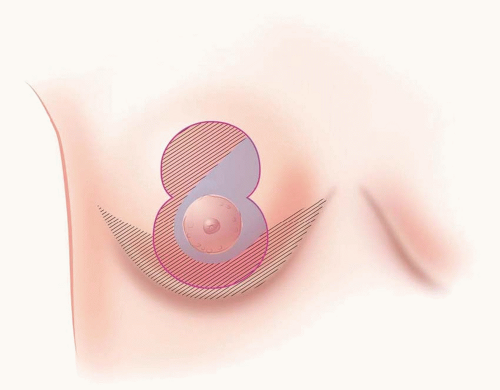

The following describes a vertical skin resection pattern using either a pure medially based pedicle or a superomedially based pedicle for the nipple-areolar complex (Figure 56.3).

Parenchymal resection: The parenchymal resection follows the Wise pattern (not just the keyhole opening) with both a vertical wedge resection and a horizontal resection of tissue below the pattern. The key is to leave a Wise pattern of parenchyma behind. When the Wise pattern (designed after a brassiere) is closed, the tissue is coned and the result is a breast with good projection and no tension on the pillar closure. It is believed that this resection pattern best resists the deforming forces of gravity over time.

Vertical skin resection pattern: The vertical skin excision is a vertical ellipse. The skin is not used as a brassiere and is only used to adapt to the new parenchymal shape. Because an elliptical excision lengthens when closed and because the IMF rises with this type of procedure, it is important to keep the skin resection pattern high on the inferior mound because some breast skin will become chest wall skin. This is important to prevent the scar from extending below the new IMF.

Medially based pedicle: A true medial pedicle is easy to inset. The inferior border of the medial pedicle becomes the medial pillar and the pedicle rotates into position without any compression or kinking. The fact that the whole base of the pedicle rotates gives an elegant curve to the inferior aspect of the breast.

Superomedially based pedicle: A superior pedicle can be difficult to inset because it usually needs to be folded. It is often necessary (and safe) to thin the pedicle to allow for an easier inset but this can lead to inferior hollowing of the breast with a concave lower breast pole at the end of the procedure. Combining a superior and medial pedicle can include both of the arteries from the second and third interspaces and therefore provide more dependable circulation. The superomedial pedicle can be backcut laterally and if the pedicle is difficult to inset, the deeper tissue (which has very little blood supply) can be removed to prevent kinking or compression. When creating a pedicle, the surgeon will often note that the bleeding occurs within the first centimeter of depth and there is very little bleeding as the dissection progresses toward the pectoralis fascia.

Markings

The key to marking a vertical breast reduction is to understand what happens to the breast after reduction and where the ideal nipple position should be. The upper breast border and upper pole of the breast will not change. Projection will improve, but the breast cannot be elevated higher on the chest wall.

It is important to understand (and point out to the patient) that some patients are “high-breasted” and some patients are “low-breasted.” The breast footprint varies from patient to patient in both vertical and horizontal dimensions. The upper breast border will not change but the IMF can rise with a medial pedicle, vertical breast reduction (and it can drop with an inverted-T, inferior pedicle reduction).

It has been recommended by many surgeons (including the author) to use the IMF as a guide to the ideal nipple position. Although this can help, the upper breast border is a more accurate landmark. There can be considerable variation in IMF level from patient to patient (and from breast to breast in the same patient). The upper breast border is the junction of the chest wall and the breast and it lies anterior to the depression just below the preaxillary fullness. The surgeon’s hand can be used to push the breast up from below to better determine its level. It is often marked by the upper extent of the striae.

Determination of New Nipple Position.

The ideal nipple position in an average “C” cup breast is about 10 cm below the upper breast border on the ideal breast meridian—which is about 10 cm from the chest midline (as drawn through the air and not around the breast). The breast meridian should not be drawn through the existing nipple position but it should be drawn through the ideal nipple position. Although 10 cm is a good guide for a vertical breast reduction, somewhat more lateral will be better for an inverted-T breast reduction because the breast base is narrowed more in the vertical approaches.

The surgeon should be able to visualize the final result. The upper pole of the breast will not change and the goal of the breast reduction will be to remove the excess inferior and lateral breast tissue. Measurements have shown that the nipple position from the suprasternal notch will remain as marked. It is a mistake to mark the nipple at an arbitrary distance from the suprasternal notch. In high-breasted patients, the ideal position might be 22 cm but in low-breasted patients it may be at 26 cm. If the nipple is marked at 24 cm (for example) from the suprasternal notch preoperatively with the patient standing, the measurement will remain the same postoperatively. The upper breast border can be raised using an implant by about 2 cm but it cannot be raised in a pure breast reduction—even when breast tissue is sutured up to chest wall.

It is best to err on the side of marking the new nipple position too lateral rather than too medial. An ideal nipple is best placed to face slightly lateral and slightly inferior. Caution: it is almost impossible to lower a nipple that has been placed too high. It is much easier to raise a nipple that is too low. When a patient lacks upper pole fullness, it is best to lower the new

nipple position so that it is not placed on an upper concavity giving an appearance of glandular ptosis.

nipple position so that it is not placed on an upper concavity giving an appearance of glandular ptosis.

In cases of asymmetry, it is best to place the new nipple position slightly lower on the larger side. This takes into account the fact that closure of a wider elliptical resection will push the ends of the ellipse further. This is not something that happens with an inverted-T type of reduction.

The new nipple position should be placed at the most projecting part of the breast. The nipple should be “centralized” not “centered” on the breast mound. The nipple should be one-third to one-half the way up the breast mound and it should be slightly lateral to the breast meridian.

Skin Resection Pattern

Areolar Opening.

The new nipple and areola are best marked with the patient standing. Although some intraoperative adjustments can be made to make sure the areola is circular, the landmarks are distorted in the supine position. The surgeon can stand back during the markings and visualize the final result because the upper portion of the breast will not change.

The areola is marked about 2 cm above the new nipple position. An ideal areola is about 4 to 5 cm in diameter. The areola can be drawn freehand or with a template. It is not necessary to make the opening “mosque” shaped—it is actually better to take more skin vertically rather than horizontally. A good template is a large paper clip—folded out it measures 16 cm. A 16 cm circumference matches a 5 cm diameter areola and a 14 cm circumference matches a 4.5 cm diameter. The actual design is not as important as making sure that the final shape is circular. It can be adjusted at the end of the procedure.

Vertical Skin Resection Pattern.

In this technique, the skin is not important in shaping the breast. Only enough skin is removed to prevent skin redundancy. The skin is not being used as a skin brassiere and it is unnecessary—and detrimental—to make the skin closure tight.

The vertical limbs can be drawn similar to that which would be drawn for an inverted-T or Wise pattern reduction. These can be determined by pushing (and slightly rotating) the breast medially and then laterally to line up the vertical limbs with the previously drawn meridians in the upper and lower chest wall areas.

Instead of extending the vertical limbs laterally and medially as would be done in an inverted-T-type Wise pattern, the vertical limbs are joined to each other well above the IMF. The final shape of the skin resection pattern with both the areolar opening and the vertical skin resection is much like a child’s snowman. The body is round with a smaller round head on top. Some surgeons have made the vertical resection come down as a “V” in order to limit the skin dog-ear, but it is important when doing this to remove adequate subcutaneous tissue inferiorly. A postoperative pucker is more often a result of excess subcutaneous tissue rather than excess skin.

The skin resection pattern should terminate well above the existing IMF. There are two reasons for this. First, the parenchyma and skin are excised as a vertical ellipse and closure results in lengthening of the incision. The closure can then push the scar below the fold. Second, when the parenchyma is removed below the Wise pattern horizontally (in addition to the resection along the vertical ellipse), the IMF will often rise. If the fold rises, the scar can fall below the new IMF. If these two factors are not taken into account, the scar might end up extending onto the chest wall skin that was previously lower pole breast skin. On average, the incision should stop at least 2 to 4 cm above the IMF in a small to medium (300 to 600 g) reduction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree