Congenital Anomalies of the Breast: Tuberous Breasts, Poland’s Syndrome, and Asymmetry

Kenneth C. Shestak

Stephen Alex Rottgers

Lorelei J. Grunwaldt

Derek Fletcher

Angela Song Landfair

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS–THE PATIENT, THE FAMILY, AND THE DOCTOR

Breast appearance in the range of “normal” is of great importance for a young woman’s sexual identity and the perception of her femininity.1 Deformities of the breast can cause issues with clothing, psychological stress, depression, peer rejection, and psychosexual dysfunction, particularly in adolescent females. In the more mature woman, there is potential problem with breast feeding. Surgeons should be aware that congenital breast deformities may be associated with abnormalities of other organ systems such as the genitourinary system.

Many breast deformities lend themselves to correction or reconstruction during or after breast development is complete. Since the breast evolves with time, and future revisions may be required, the timing and method of reconstruction is determined only after a detailed discussion with the patient and her family. They must understand the realities and the limitations of a proposed procedure. Honest communication is central to the process of informed consent and is the foundation of a healthy doctor-patient relationship.

Pediatric breast deformities are divided into hyperplastic, hypoplastic, and posttraumatic defects. Each represents various pathologic entities and a spectrum of disease which warrants consideration on an individual case basis. Treatment goals focus on accurate diagnosis, appropriate timing, and technique selection in order to optimize the cosmetic outcome and best satisfy the psychological needs of the patient.

Embryology and Development

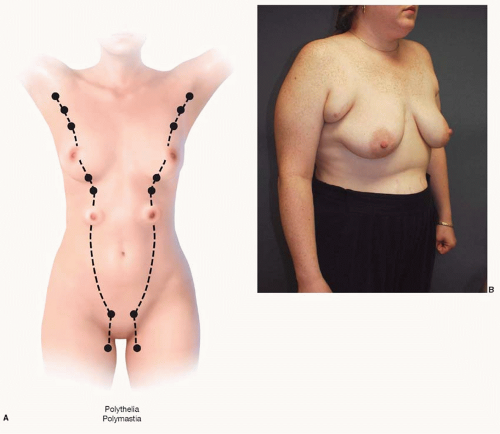

Breast development begins between the fifth and seventh weeks of uterine life. At this time, the mammary lines form as bilateral linear condensations of ectoderm extending from the axillary areas to the inguinal regions. This ectoderm comes to lie below the surface of the embryo and at this point they are called the mammary ridges or milk lines which can potentially form the breast tissue (Figure 64.1A). In most instances, however, only a small focus of mammary tissue overlying the thoracic region in the region of the fourth intercostal space (ICS) persists while those in the other areas regress. The tissue aggregate in the fourth ICS continues to divide and thicken, and by the eighth gestational week ectoderm has invaded into the underlying mesenchyme in a branching pattern. At 16 weeks of gestation, 15 to 25 epithelial branches have formed, but canalization has not begun. It is during the third trimester, under the influence of placental sex hormones (mainly estrogen and progesterone), that these epithelial branches are canalized, and primitive breast ducts begin to form. At 32 weeks, differentiation of the parenchyma into lobules begins. The nipple-areolar complex (NAC) begins to form and is completed in the early postnatal period. Branching and canalization continue after birth and through early childhood.1

Breast development is relatively quiescent throughout childhood. Further growth and maturation is initiated at the time of thelarche. With the increased growth at thelarche, the breast progresses through a series of morphological stages, as described by the Tanner classification.2 A Tanner stage 1 breast is prepubertal, with no appreciable breast parenchyma and slight nipple elevation. At thelarche, the breast progresses toward Tanner stage 2 with enlargement of the NAC and elevation of the breast/nipple as a small mound. Tanner stage 3 describes a breast with further enlargement and a smooth transition between the breast and areola without separation of their contours. As the breast continues to enlarge toward Tanner stage 4, the nipple and areola enlarge more and project as a secondary mound above the breast contour. Finally, at the final Tanner stage 5, the breast achieves its mature size and form. The areola has receded and forms a continuous contour with the surrounding breast.2 Most females would have achieved full breast maturity by 16 to 18 years of age; however, the evolution of the breast form continues as a lifelong process.

Hypoplastic Disorders

Various conditions result in hypoplasia or aplasia of the breast. Hypoplasia in the form of mild asymmetry, constricted breast deformities, and mild presentations of Poland syndrome is much more common than aplasia of the breast. Both the constricted breast deformity and Poland syndrome will be discussed in depth below.

Terms used to describe breast aplasia include athelia, isolated absence of the NAC; amasia, absence of breast parenchyma; and amastia, absence of both the breast tissue and the NAC.1 Though this nomenclature would suggest otherwise, athelia and amasia do not seem to occur without each other. These conditions and their distinctions are delineated by Trier.3

Hyperplastic Disorders

Hyperplastic disorders include the excess development of mammary tissue in an otherwise normal anatomic location as well as the development of breast tissue or nipple-areolar structures in locations remote from the normal thoracic distribution. Treatments require simple observation, excision, or breast reduction techniques. Accurate diagnosis and assessment of the severity of the deformity is essential, along with counseling the patient and the family.

Virginal Hypertrophy

Virginal hypertrophy of the breast is a rare condition that results in excessive, rapid, and often non-yielding proliferation of breast tissue. The etiology is unclear, but pathologic

evaluation seems to suggest an abnormal sensitivity of the glandular tissue to the stimulatory effect of estrogen in the setting of normal hormonal levels. The condition may be unilateral or bilateral. Patients often exhibit a rapid onset of breast hypertrophy only months after the initiation of breast growth that quickly becomes symptomatic with the typical signs of macromastia (shoulder and neck pain, bra strap grooving, and rashes) along with tender breast parenchyma, thinned skin, striae, and dilated veins. They will generally present because of the rapid progression.4

evaluation seems to suggest an abnormal sensitivity of the glandular tissue to the stimulatory effect of estrogen in the setting of normal hormonal levels. The condition may be unilateral or bilateral. Patients often exhibit a rapid onset of breast hypertrophy only months after the initiation of breast growth that quickly becomes symptomatic with the typical signs of macromastia (shoulder and neck pain, bra strap grooving, and rashes) along with tender breast parenchyma, thinned skin, striae, and dilated veins. They will generally present because of the rapid progression.4

Treatment is ultimately surgical. Breast reduction techniques are standard as a first-line therapy, and goals should be to first achieve an improved breast size and symptom relief. Improved symmetry in asymmetric cases of hypertrophy is also important. Some patients require additional breast reduction operations, and mastectomy may be considered in refractory cases.4 Pharmacologic therapy in the form of medroxyprogesterone acetate, dydrogesterone, tamoxifen, and bromocriptine have been employed in the past but side effects have limited their use.1,4

Giant Fibroadenoma

Like virginal hypertrophy, giant fibroadenomas result from abnormal sensitivity of the breast tissue to normal hormonal levels. This entity is a discrete benign tumor that enlarges rapidly and causes asymmetric enlargement of the breast.5 The treatment is also surgical excision. This is accomplished through breast reduction techniques with a pedicle design and excision pattern that incorporates the mass into the resection specimen and positions the pedicle in the location of the greatest amount of normal breast tissue to preserve breast fullness.5 Concurrent matching procedures on the contralateral breast or delayed mastopexy/augmentative procedures may be required to achieve symmetry. Timing for surgery is driven by the rate of tumor growth. Excision may be necessitated prior to completion breast development to limit the distortion of the breast and to optimize the aesthetic result.

The differential diagnosis for fibroadenoma includes cystosarcoma phyllodes, which can be difficult to differentiate based on a biopsy. Since the incidence of phyllodes tumor is less than 1.3%, treatment should include simple excision of the mass followed by consideration for mastectomy or adjuvant therapy if the diagnosis of a malignant phyllodes tumor is made.6 Consultation with surgical oncology or pediatric surgery is appropriate in this circumstance.

Polythelia/Polymastia

Polythelia, the presence of accessory nipples, is a common pediatric abnormality and has a reported incidence as high as 5.6%.1 Polymastia, the development of supernumerary breast tissue, with or without a nipple or areola, is much less

common. Both are presumed to arise from an incomplete regression of the mammary ridge during embryonic development, leaving residual mammary tissue along the “milk line” between the axilla and inguinal region. Supernumerary nipples typically occur caudal to the true nipple and can present as a partial or complete nipple, partial or complete areola, or a combination. They may be isolated or multiple. While supernumerary nipples are often found during the neonatal period or childhood, accessory breast tissue, either with or without an accessory nipple, is often not identified until the tissue hypertrophies because of puberty, pregnancy, or lactation. Polymastia most often occurs with axillary breast tissue7 (Figure 64.1B). Some authors differentiate the terms “polymastia” and “ectopic breast tissue.” When used strictly, polymastia refers to breast tissue occurring along the “milk line.” “Ectopic breast tissue” refers to the remarkably rare occurrence of breast tissue in other locations in the body.

common. Both are presumed to arise from an incomplete regression of the mammary ridge during embryonic development, leaving residual mammary tissue along the “milk line” between the axilla and inguinal region. Supernumerary nipples typically occur caudal to the true nipple and can present as a partial or complete nipple, partial or complete areola, or a combination. They may be isolated or multiple. While supernumerary nipples are often found during the neonatal period or childhood, accessory breast tissue, either with or without an accessory nipple, is often not identified until the tissue hypertrophies because of puberty, pregnancy, or lactation. Polymastia most often occurs with axillary breast tissue7 (Figure 64.1B). Some authors differentiate the terms “polymastia” and “ectopic breast tissue.” When used strictly, polymastia refers to breast tissue occurring along the “milk line.” “Ectopic breast tissue” refers to the remarkably rare occurrence of breast tissue in other locations in the body.

Supernumerary breast tissue may be removed surgically with placement of closed suction drains. If left in situ, regular monitoring for breast pathology and malignancy must be performed, as this accessory mammary tissue is subject to an equal rate of breast malignancy as the normally positioned gland. Treatment of a mass arising within this tissue must be treated with the same oncologic principles as any breast mass.7

Gynecomastia

Though usually seen by plastic surgeons in its most severe form, gynecomastia is by far the most common pediatric breast deformity occurring in up to 65% of pubescent males.8 Gynecomastia is a clinical term denoting enlargement of the male breast such that it appears female. It is most often related to proliferation of ductal epithelium as no true acinar development occurs. Most often it is idiopathic in its etiology, but the proliferation can be a symptom of an underlying pathologic process. “Physiologic” gynecomastia is common during three periods of a male’s lifespan. Neonates often exhibit small enlargement of the breast bud and may secrete colostrum transiently as a response to maternal estrogens. As stated above, the fluctuating hormonal milieu of early puberty produces gynecomastia in up to 65% of males between 14 and 16 years of age, and declining androgen production seen in later life can lead to a relative estrogen excess and to the development of gynecomastia. If other signs of pubertal development are present, a standard history and physical suffices for evaluation, but in the absence of normal pubertal development, a more extensive evaluation is required. In most males, pubertal gynecomastia is mild and transient.1

While gynecomastia may be considered normal in these age groups, a history and physical exam should be performed to rule out common causes such as testicular cancer, pituitary tumors, adrenal tumors, liver disease, paraneoplastic syndromes, Klinefelter’s syndrome, thyroid disease, renal failure, myotonic dystrophy, human immunodeficiency virus, marijuana use, alcohol, anabolic steroids, and medications known to cause gynecomastia.1,8 The most common etiology of gynecomastia in adolescents is idiopathic, while in patients over 40 years of age it is most often drug induced.

When significant gynecomastia persists for 2 years beyond puberty, surgery is often indicated to recreate a normal chest contour and nipple location with limited scaring. The first procedures described for gynecomastia focused on subcutaneous mastectomy through periareolar or various other incisions.1 This remains the best approach in cases of dense fibrous tissue that is located in a subareolar plane. Others have advocated the use of ultrasound-assisted liposuction as the standard first-line approach followed by secondary excision only for a marked residual deformity.8 The ideal approach in most cases is a combination of these, with direct periareolar excision of the central, fibrous breast bud followed by liposuction to contour the peripheral breast area representing the authors’ preferred method. Severely redundant skin may be excised primarily with a periareolar or vertical skin excision, but we believe that the significant elasticity of youthful skin often allows adequate retraction of skin excess such that primary skin excision is not warranted in most cases. If the skin redundancy persists beyond 6 to 12 months postoperatively, excision is undertaken.9 Care is taken during resection to avoid over-resection and the creation of a “dishing” or nipple retraction. Regardless of the technique used, postoperative care involves the use of closed suction drains following excision, prolonged compressive garment application (for at least 6 weeks), and twice-daily deep tissue massage instituted at 1 week postoperatively along with abstinence from heavy exercise for 1 month. These adjuncts aid in tissue re-draping, reduce edema, and limit formation of seroma and hematomas. The cited references8,9 provide an excellent overview of the subject.

DEVELOPMENTAL BREAST ASYMMETRY–APPROACHES TO TREATMENT

Both hypoplastic and hyperplastic breast disorders represent a spectrum of disease. Patients often present with bilateral manifestations of breast hypoplasia, breast constriction, and hyperplasia. Significant asymmetries can result due to variable expressions of these entities. The key to achieving an outcome that pleases both the patient and the surgeon is to correct identification of abnormalities producing the asymmetry. The breast morphology is examined to determine whether the problem is unilateral or bilateral. As discussed below, bilateral correction is usually required.

An essential aspect in formulating a treatment approach is understanding what the patient perceives as abnormal, which breast she feels is preferable, and what her goals of treatment are. Patient and family are educated that breast symmetry and contour will be improved but perfection is not realistic. Perfection, the goal of every procedure, is rarely achieved. If patients understand this before surgery, they are generally pleased with the result.

In some instances, it is possible to operate on one breast, most often when a breast reduction alone will produce improved symmetry. In our experience, the best and most permanent results are seen in cases of breast asymmetry where a patient has a smaller, but aesthetically pleasing breast and wants the larger breast reduced to match the smaller breast. A breast reduction or mastopexy can improve symmetry, correct ptosis in the larger breast, and avoid the potential problems of implant-based reconstruction/augmentation. A unilateral reduction mammoplasty limits the number of variables at play, increasing the predictability of the final outcome.

In most cases, the clinical scenario is not so simple however. In our experience, most surgical procedures involve bilateral surgery. Differential reductions, mastopexies, augmentations, and most frequently combinations of these must be employed to achieve the most harmonious balance between the breasts. Careful consideration is given to each breast and each breast abnormality within the context of the patient’s expectations. An explanation of surgical details such as incision placement and a discussion of implant complications are provided. In addition, the patient is informed that the breast appearance will most likely change with weight fluctuation, pregnancy, and aging regardless of the procedures undertaken. The important elements of an informed consent are explained to both the patient and her parents.

Timing for reconstruction is also addressed with the patient and her family. As the breast is constantly developing and evolving in form, it is usually best to delay treatment until the patient has finished growing and her breasts are mature (patients who are 16 years of age or older).

We employed this strategy in the patient shown in Case 2. She was seen at age 15 with a combination of right breast hypoplasia with breast constriction and left breast hypertrophy (Figure 64.2A, B). The best approach was to wait until the summer prior to her senior year in high school at which time she underwent a periareola augmentation/mastopexy on the right side with the partial subpectoral placement of a saline implant and a left vertical mastopexy. She is shown at 4 months following surgery (Figure 64.2C, D) with improved symmetry.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree