div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

31. Perineal Urethrostomy: A Pearl in Failed Urethral Reconstruction

31.1 Introduction

Urethroplasty surgery for urethral strictures is the preferred option to restore durable urethral patency offering excellent success rates. However, failure rates can be as high as 50% [1] for the most challenging patient presentations. In particular, patients with panurethral strictures (most commonly related to lichen sclerosus) and patients with multiple previous failed urethroplasties, such as hypospadias cripples, are considerably difficult to manage. Tissue scarring and a decrease in vascularity -be it due to the sclerosing disease process or secondary to recurrent instrumentation- impede wound healing and reepithelialization making stricture recurrences and in case of hypospadias cripples also fistula formation common. In addition to urethral complications, these patients are found to experience a diminished quality of life related to voiding and sexual dysfunction as well as depression [2, 3].

Often viewed as a last resort prior to abandoning the urethral outlet, creation of a perineal urethrostomy (PU) is a highly successful option for men with complex urethral stricture disease , and in some conditions may even halt the progression of disease [4]. However, amongst urologists, there appears hesitation to perform this procedure. In surveys of practicing members of the American and Dutch Urological Associations completed in 2002 and 2008, respectively, less than 10% of urologists had performed a PU in the previous year [5, 6]. Yet in recent years as the field of reconstructive urology continues to advance it appears that perineal urethrostomies are increasingly considered. Fuchs et al. noted a nearly ten-fold increase in PU procedures from 2008 to 2017, with also a trend towards performing the procedure in younger patients likely reflecting improved awareness of the limitations of tissue transfer [7].

31.2 General Indications

In general , PU is a reversible procedure, and this is utilized during staged urethroplasty. A generation of a neomeatus in the perineum is essential during the first-stage. In this setting, despite the intention for a complete reconstruction six or more months later, many patients may ultimately find PU as an acceptable diversion and elect to forgo the second stage. In fact, in those undergoing staged urethroplasty, only 24–58% of men pursued second stage, leaving 42–76% with a functional perineal urethrostomy [4, 8, 9].

More commonly, however, definitive PU is performed and the general indication is in individuals with complex anterior urethral strictures. Compared to extensive urethral reconstruction, PU is a relatively minor surgical procedure associated with earlier return to normal activity and catheter removal, while avoiding the morbidity of graft harvest site morbidity and maintaining more typical anatomy for aesthetic reasons. As such, PU may be a more sensible procedure in the elderly or in those with severe medical comorbidities for whom a prolonged surgery may be associated with higher perioperative morbidity and mortality [4]. Other times, the surgeon may recommend a PU due to poor quality of urethral and penile tissue, exhaustion of graft materials, and understanding of the disease process, which can contribute to inadequate reconstruction [4, 9]. Aptly put by Peterson et al., “heroic measures may not be justified” [4]. Finally, patients who would otherwise be candidates for a single-stage repair may elect to undergo PU instead of complex urethroplasty due to a history of multiple prior failed procedures and treatment fatigue. Barbagli et al. reported that patients electing PU instead of a complex urethroplasty were a mean age of 53 years, had undergone on average 4.5 procedures for hypospadias repair or 4.1 failed urethroplasty for other urethral conditions, and were unwilling to accept the possibility of another failed urethroplasty [9].

Outside of urethral stricture disease, a PU may be indicated in patients with traumatic or penile amputation. Following penile trauma or in the setting of penile or urethral malignancy, PU may be utilized as an alternative to placement of a suprapubic catheter or avoid more extensive surgery to create a urinary outlet such as appendicovesicostomy or even supravesical diversion such as an ileal conduit. The PU permits continent voiding and avoids complications associated with prolonged catheter use including urinary tract infection, bladder calculi, catheter blockage, and increased risk of squamous cell bladder carcinoma or risks of extensive surgery.

It should be noted that not all patients with urethral pathology should be considered for creation of PU. In patients with coexistent proximal urethral disease (posterior urethral stenosis or bladder neck contracture), a PU would obviously not relieve obstructive symptoms. In patients with urinary incontinence, creation of a PU could worsen urine leakage by bypassing the stricture, which in many cases comprises the patient’s continence mechanism. In this setting, continuous leakage of urine through a PU is likely to cause wound complications. Additionally, the presence of a PU would make subsequent placement of an artificial urinary sphincter more challenging technically as well as likely increase the risk of complications [10].

31.3 Perineal Urethrostomy Techniques

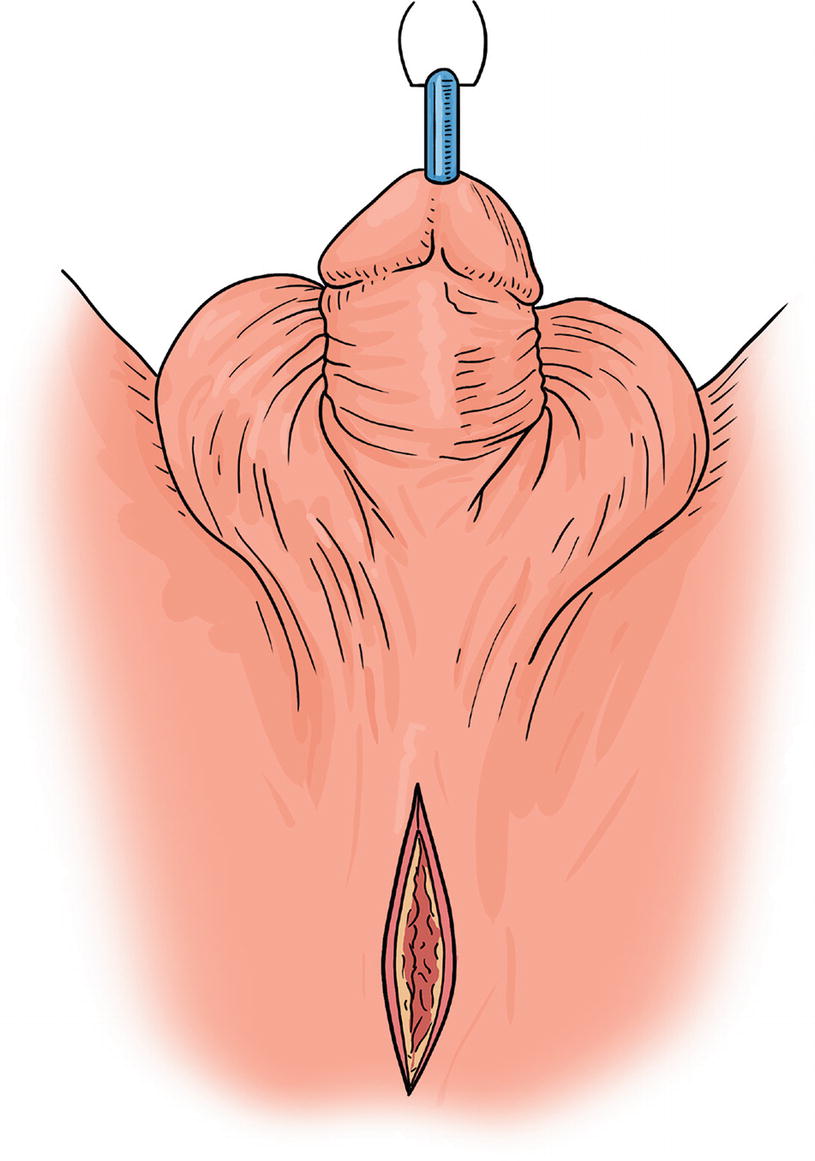

There are several techniques described to generate a PU and approaches can broadly be divided into two categories: those associated with transection of the urethra and non-transecting techniques.

Non-transecting techniques such as the Johanson and Blandy techniques preserve the urethral plate, and thereby retrograde blood supply from the dorsal penile artery. This may decrease the rate of postoperative complications, specifically stenosis of the neomeatus [11]. Additionally, by maintaining the urethral plate, these techniques allow for the possibility for the urethra to be re-tubularized at a later date. In contrast, advantages of transecting techniques, such as the 7-flap, lotus petal flap, and also augmented PU techniques, are a more complete mobilization of the proximal urethral stump. This facilitates a tension-free anastomosis, especially in patients with increased skin-to-urethra length (e.g., obese patients or patients with very proximal urethral strictures). However, while generally also reversible, the urethral transection and ligation of the distal urethra makes a subsequent reversal a more complex endeavor.

31.3.1 Non-transecting Techniques

31.3.1.1 Johanson Technique

Originally described in 1953 as the first-stage of a staged urethroplasty for pendulous urethral strictures, the Johanson technique has been adapted for use in the bulbar urethra for staged procedures as well as for permanent diversion in the form of PU [12]. In principle, the Johanson technique for PU creation involves marsupialization of the urethra to adjacent perineal skin and serves as blue-print of generating a PU as its evolution by the more elaborate techniques discussed below have some elements in common with the Johanson technique.

Johansen PU : Midline incision over the urethra

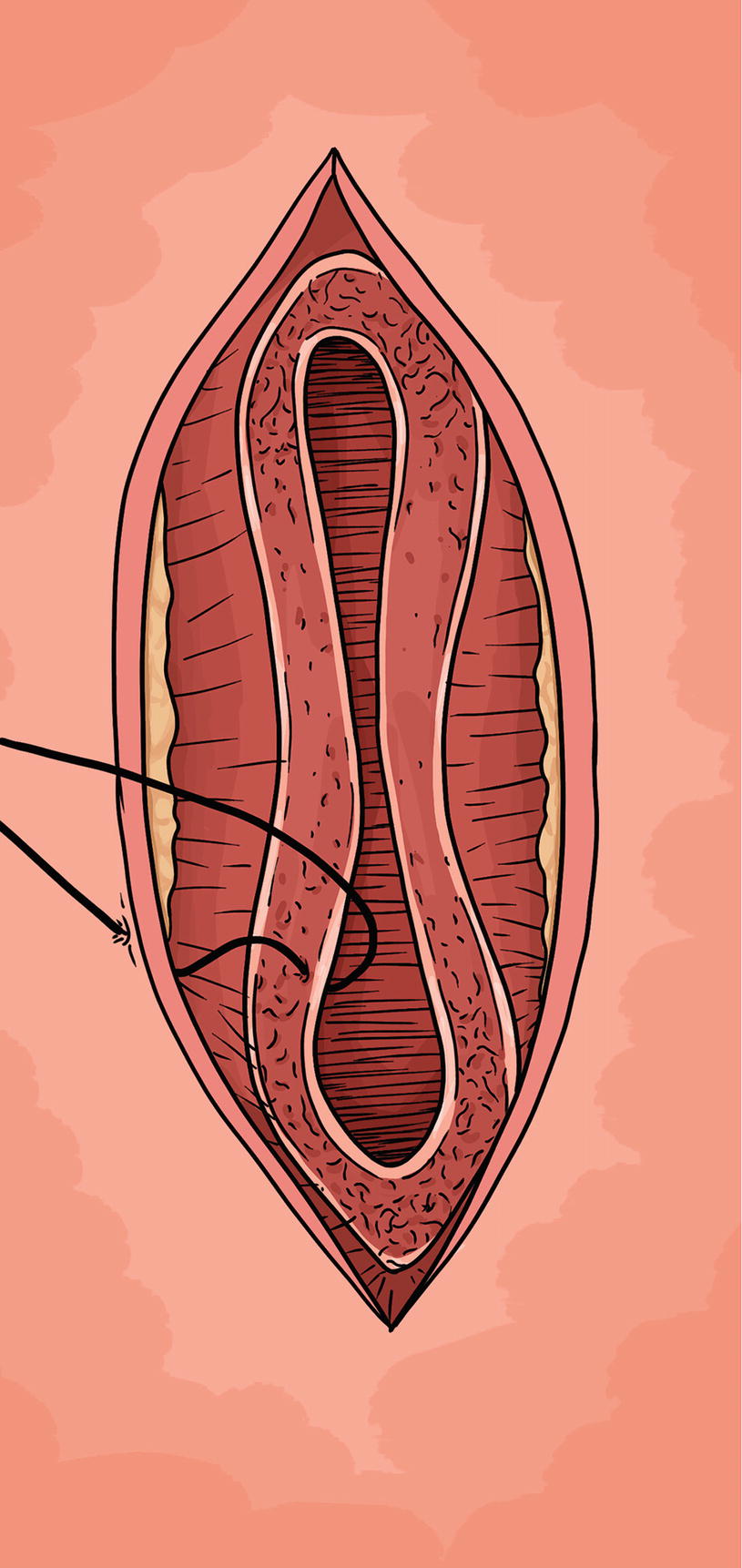

Johansen PU : The urethra is opened longitudinally for several centimeters and the skin anastomosed to corpus spongiosum and mucosa

In the event that the urethrostomy cannot be matured to the perineal skin in a tension-free fashion, scrotal skin can be invaginated towards the urethrotomy, with a vertical incision made along the median raphe of the scrotum to be used for stoma maturation [1, 8]. A urethral catheter is placed through the neomeatus but can typically be removed within 1 week .

The Johanson technique is a familiar concept to most reconstructive urologists due to its use as a first-stage approach for staged urethroplasty. However, due to the limited elasticity of the perineal skin, there may be significant tension when maturing the urethrostomy, particularly at the posterior-most aspect. This may predispose the incision to wound dehiscence and subsequent stenosis of the neomeatus. To address this concern, an invaginated scrotal flap as described above should be considered albeit this can be inconvenient for voiding. Alternatively, McKibben describe the utilization of a Z-plasty technique on the inferior aspect of the perineal incision to construct a tension-free urethrostomy with excellent success [14]. Regardless, use of this approach may be best reserved for thin individuals with pliant perineal skin in whom a tension-less anastomosis is more feasible.

31.3.1.2 Blandy Technique [15, 16]

Developed as a modification of the Johanson technique due to high stenosis rate at the proximal apex of the PU, this technique was first described in 1968 [15]. By developing an inverted U-shaped scrotal flap, this approach can be used as a first-stage of a staged urethroplasty or for definitive PU.

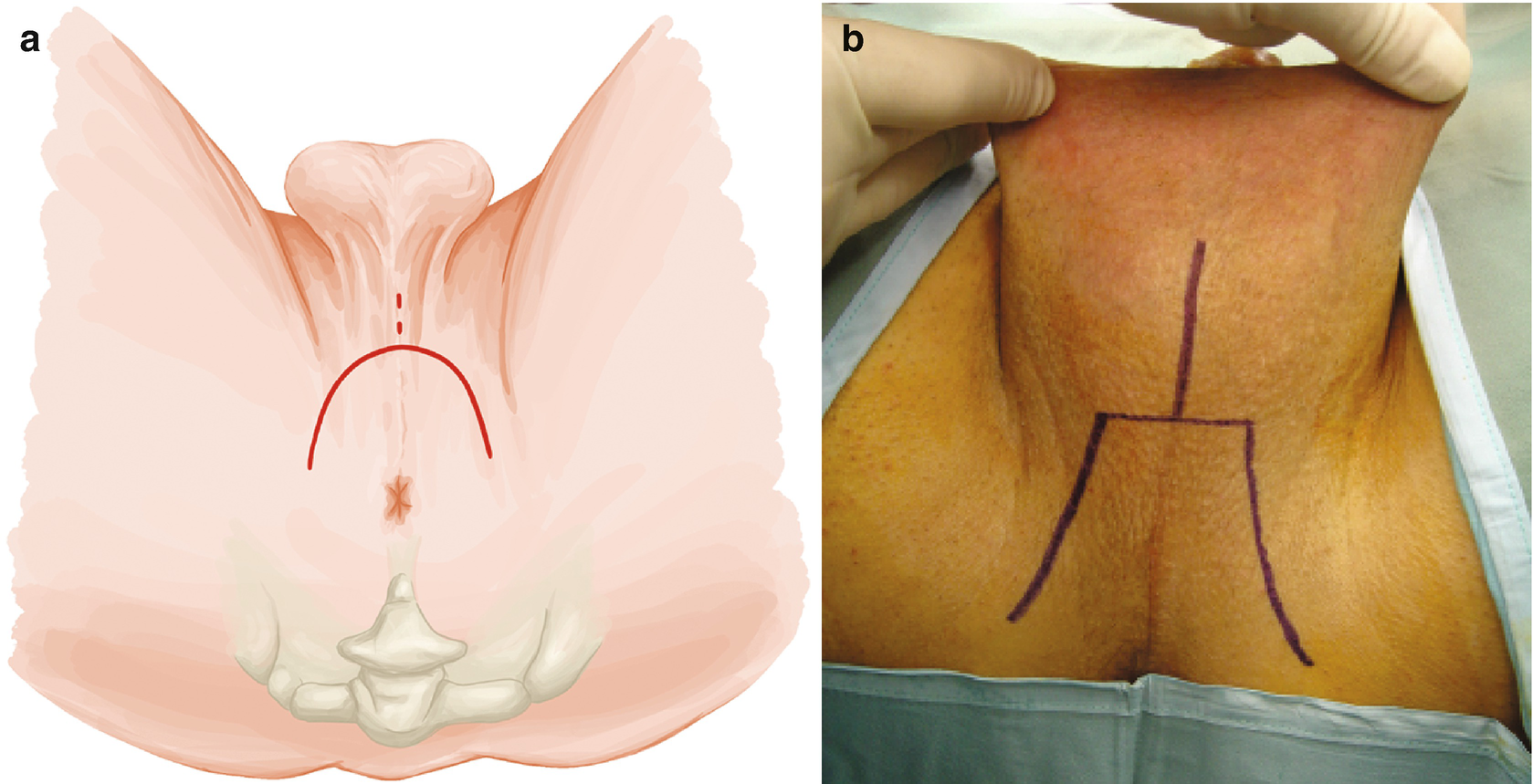

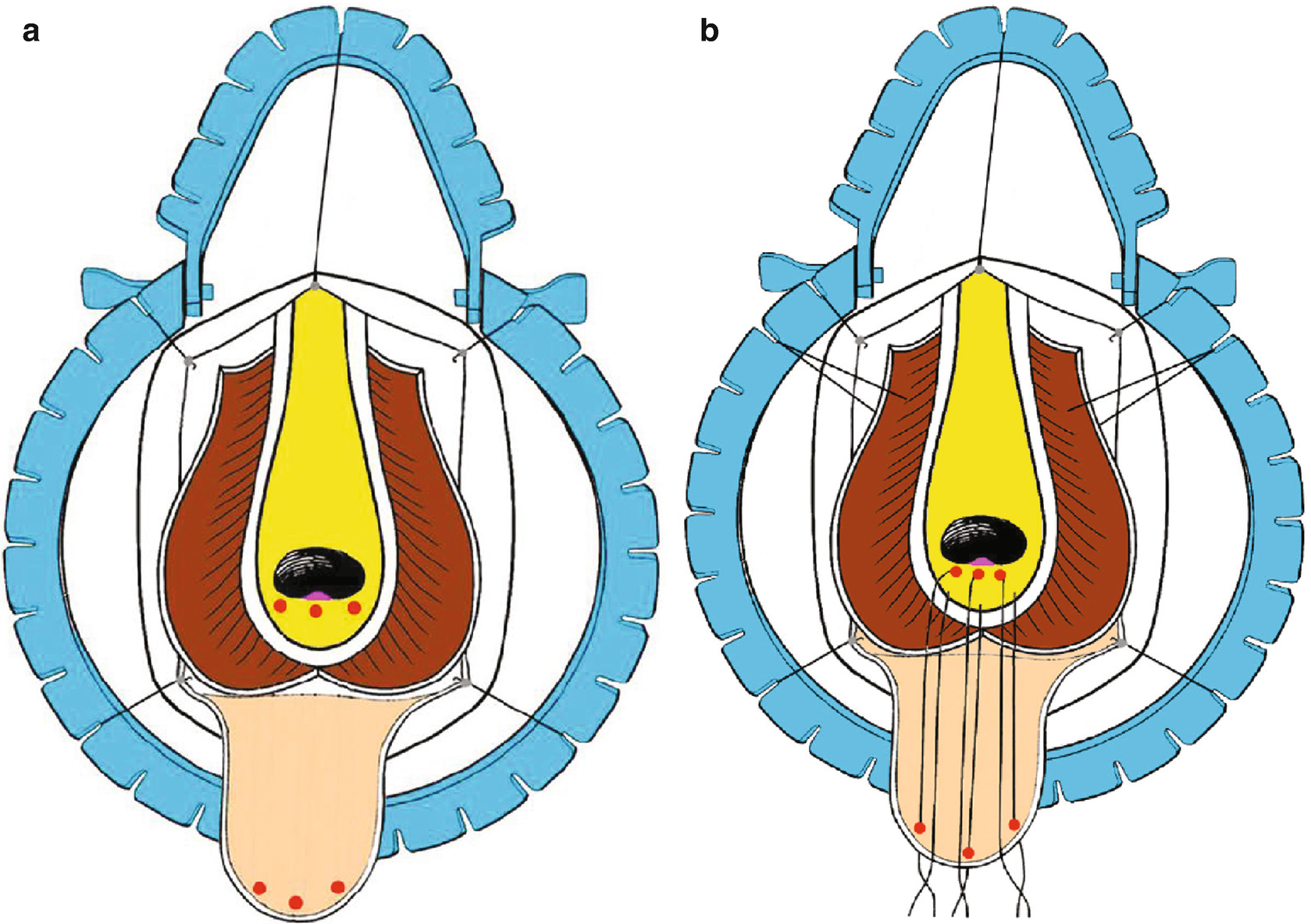

Blandy PU: Outline of the skin incision either as inverted U (Panel a) or as trapezoid (Panel b). Note the perpendicular incision in the midline of the scrotum

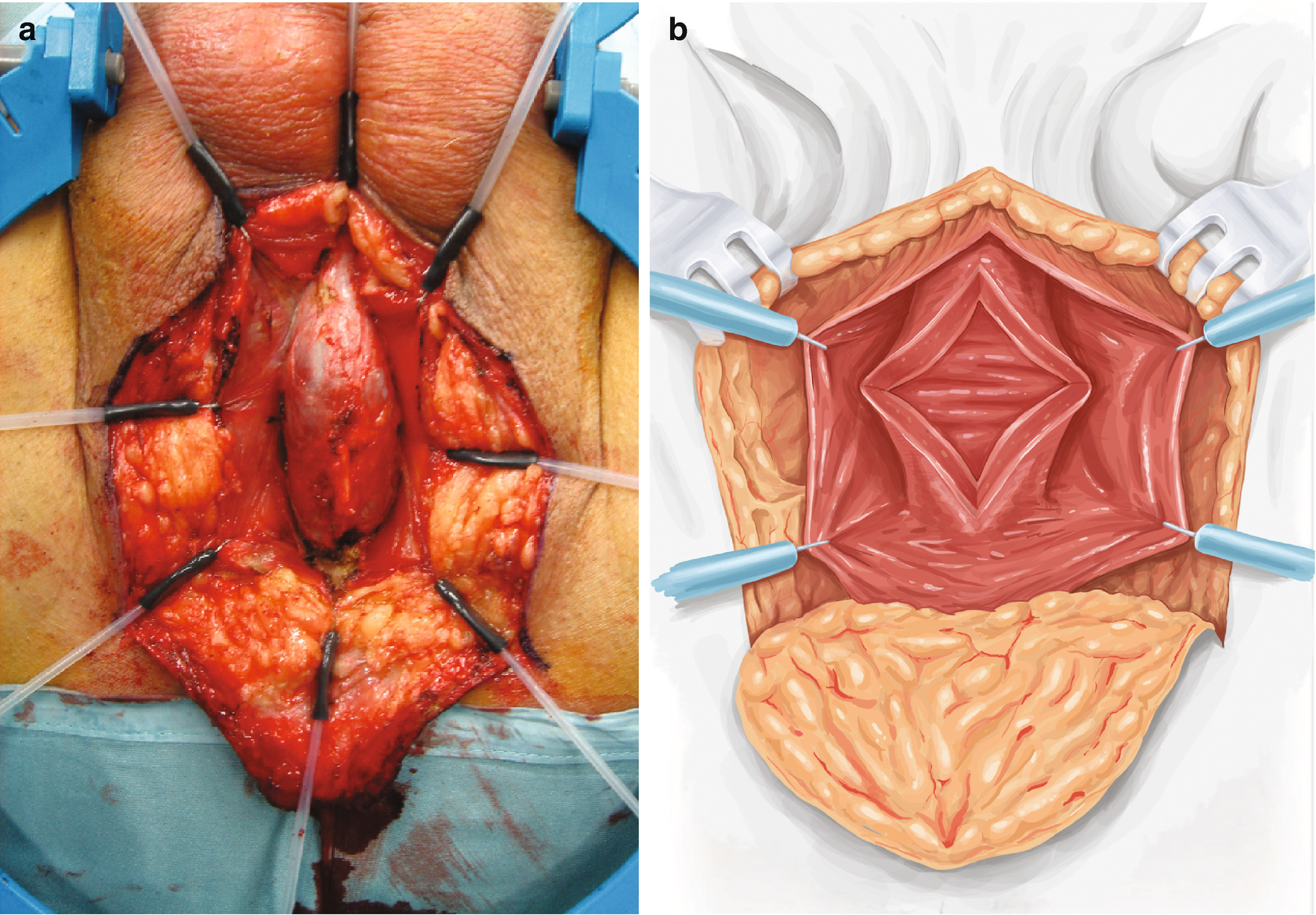

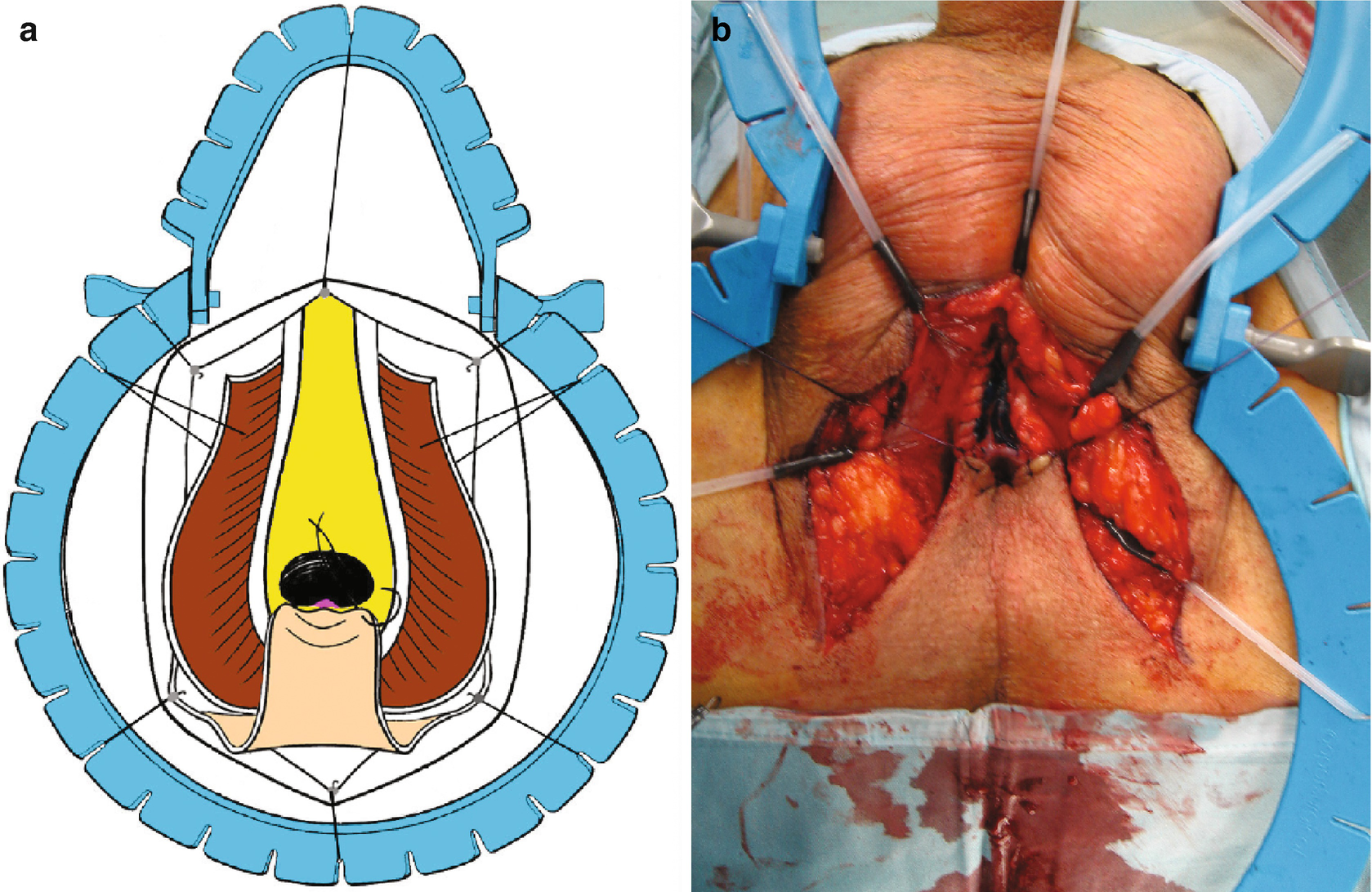

Blandy PU : The urethra is exposed (Panel a) and then opened (Panel b). A ring retractor with hooks helps to expose the field

Blandy PU : A running stitch through mucosa and corpus spongiosum closes the corpus and controls bleeding

Blandy PU : Three apical sutures are marked and passed in front of the verumontanum and placed in corresponding sites on the apex of the inverted U-shaped perineal skin flap (Panel a and b)

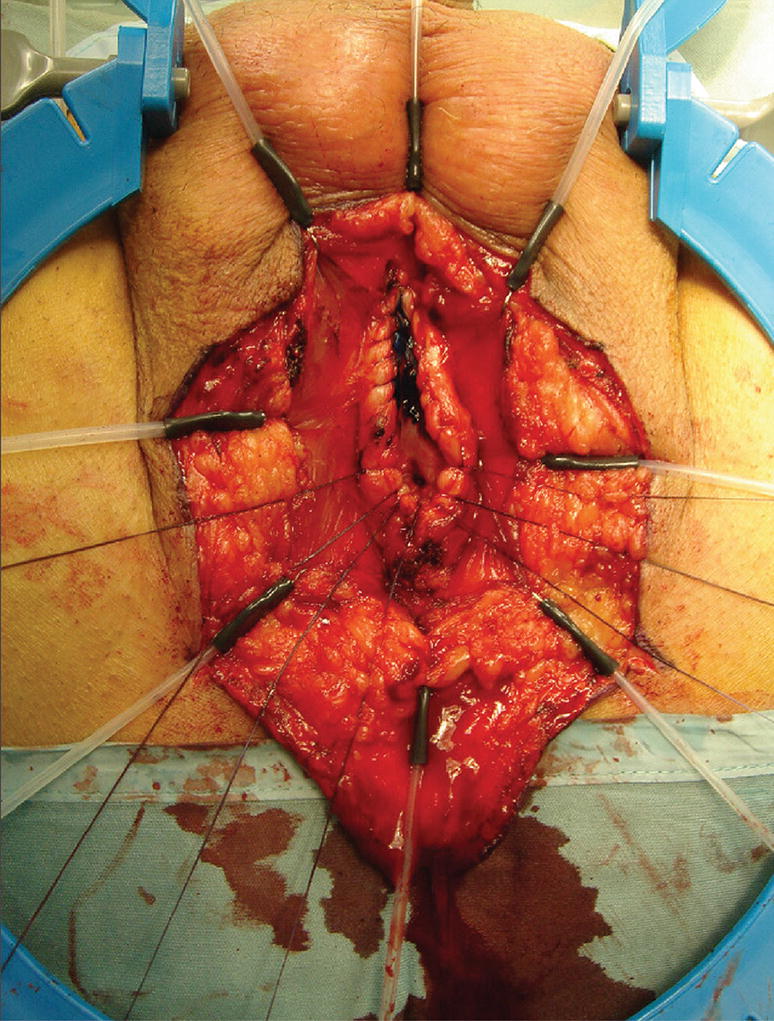

Blandy PU : Upon tying the 3 sutures, the perineal skin flap is parachuted into the proximal urethral mucosa (Panel a and b)

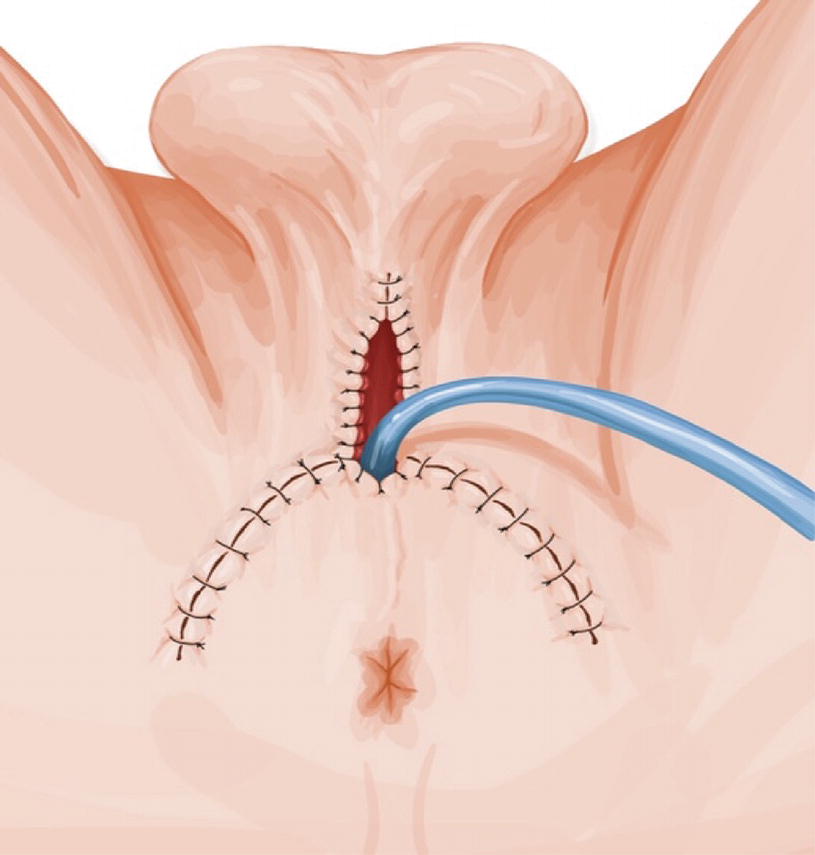

Blandy PU : Remaining perineal skin is sutured to the urethral plate and remaining skin defect closed. A 20 Fr urethral catheter is placed and removed after 10 days

The main drawback of the Blandy technique is that it relies on an accurate pre-incision assessment of the length of the flap needed to construct a tension-free anastomosis. Unfortunately, the preoperative assessment of urethral stricture disease is imperfect, with one study noting a correlation coefficient of only 0.69 between preoperative RUG and intraoperative stricture measurement [17]. It follows that if the stricture extends more proximally than expected before the initial incision, the flap may not be long enough to ensure a tension-free anastomosis and predispose to PU failure. Also, in its original report, about 10% of patients required a revision due to necrotic tip of the flap and some patients needed to self-dilate to break down skin bridges between suture lines. [16]

31.3.2 Transecting Techniques

31.3.2.1 7-Flap Technique

The 7-flap technique was first described in 2011 by French et al. [18] This approach utilizes a lateral-based perineal skin flap to create the urethrostomy. It also employs a vertical midline perineal incision, affording flexibility if a one-stage urethral reconstruction is intended but not possible and instead a PU is necessary. Conversely, if a PU is being pursued but an orthotopic reconstruction is instead deemed possible this can be performed through this incision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree