div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

27. Surgical Urethral Reconstruction After Failed Urethral Stents

Keywords

Urethral stentUrethroplastyUroLumeMemokathSurgical techniqueResults27.1 Use of Stents for Urethral Stricture

Urethral strictures are typically caused by inflammation or trauma. Endoscopic treatments of a urethral stricture is a controversial issue as the success of different endoluminal therapeutical options depends on numerous factors related to the procedure type, the stricture etiology, length and location, the degree of spongiofibrosis and the magnitude of the inelastic scar within stricture. Visual urethrotomy evolving full-thickness incisions through the depth of the scar or urethral dilatation also result in further scarring after damage of epithelium, spongiosal tissue and surrounding muscle fibers.

Urethral stents were introduced in the 1980s with the intention to prevent scar contraction after dilatation or urethrotomy. Both permanent and temporary stents were introduced, both being subject to either staged removal or periodic change. Initially the stents were designed to be placed after dilatation as an alternative to internal urethrotomy for recurrent bulbar strictures. Unfortunately their widespread use has led to very disappointing results, not only due to complications, but also due to the daunting task of dealing with removal of the embedded prosthesis and difficult late urethral reconstruction [1].

27.1.1 History of Permanent Stents

The self-expanding Wallstent was developed for vascular disease by Hans Wallstent, taking into account a wire banding braided technology also used to the manufacturing of coaxial cables. In Urology it mainly served to maintain the patency of a stenosed bulbar urethra after dilatation as initially described by Milroy in 1988 [2]. Treatment of urethral stricture using UroLume (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minesota) urethral stent was approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 1988 and since then distributed in many countries until being discontinued in 2011. This endoprosthesis manufactured in Switzerland was biocompatible, flexible and self-expanding, and rapidly evolved to be considered a good alternative to dilatation and internal urethrotomy to treat recurrent bulbar strictures [3]. At that time urethroplasty was too often performed only after repeat failure of endoscopic methods because urologists erroneously believed in a “reconstructive surgical ladder ” and only considered urethroplasty after repeat failure of endoscopic methods [4, 5].

2.5 cm UroLume stent on bulbo-membranous urethra with hyperplastic overgrowth causing restenosis inside the prosthesis

Two 2.0 cm UroLume stents placed on pendulous and bulbar urethra with re-stricture adjacent to both proximal and distal ends of the tandem stented segment

We really do not know how many permanent stents have been explanted in the long term and there is no knowledge of how many patients are still bearing these type of endoprosthesis. Still though, despite it is now more than 15 years that stents they are not available the patients return with re-strictures and pose a very interesting challenge to the reconstructive centers worldwide [10].

27.1.2 Temporary Stents

Results with the temporary stents were not as disappointing as those with the permanent stents, which would explain why they are still in use today being used occasionally for treatment of recurrent urethral strictures, post-prostate cancer treatments, urethrovesical anastomotic stenosis, recurrent ureteral stenosis and uretero-ileal anastomotic stenosis as well.

Memokath (Pnn Medical, Denmark) is a biocompatible endoprosthesis made of nickel and titanium alloy (nitinol) that anchors by expansion of its proximal end in responce to a warm water instillation after being inserted through a lumen opened by direct vision internal urethrotomy or progressive dilatation. In contrast to permanent stents, it is not embedded into the mucosa. This quality in combination with its thermal shape-memory allow for an easy transurethral removal. However, due to the stent’s constant exposure to urine, the initial reports also described luminal narrowing due to encrustation in 1 out of 4 patients and recurrent stricture in 1 of 5 [11]. Complications were shown to increase with time as epithelial hyperplasia tends to develop at around 1 year follow-up [12], which makes this device useful only for temporary stenting.

A multicenter randomized controlled trial demonstrated that patients with recurrent bulbar urethral stricture treated with Memokath stent after dilatation or internal urethrotomy have maintained their urethral patency longer than those treated with dilatation or DVIU alone [11]. However, another feasibility study where Memokath stent was used for treatment of recurrent bulbar strictures, has concluded that this treatment has significant side-effects and is not clinically useful [13]. Also urethroplasty in these cases is totally feasible and is very effective to achieve and maintaining urethral patency after non-desired Memokath urethral re-stenting [14].

Allium stent (Allium Medical, Caesarea Industrial Park, Israel) has a nitinol skelton covered with a biocompatible polymer that is resistant to urine environment, thus acting as an impermeable walled tube that prevents tissue ingrowth into the lumen. It can be removed easily, even 1 year after implantation, by pulling its downstream end with an endoscopic forceps causing the stent to unravel and to be taken out as a tape. Clinical experience with Allium is scant, but at least this device does not seem to suffer migration or problems at the time of endoscopic extraction [15, 16].

27.2 The Problems of Urethral Stenting

3.0 cm UroLume stent with severe distal urethra restenosis in a patient performing long-term auto-dilatation before definitive stent removal and urethral reconstruction

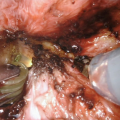

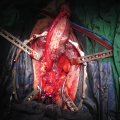

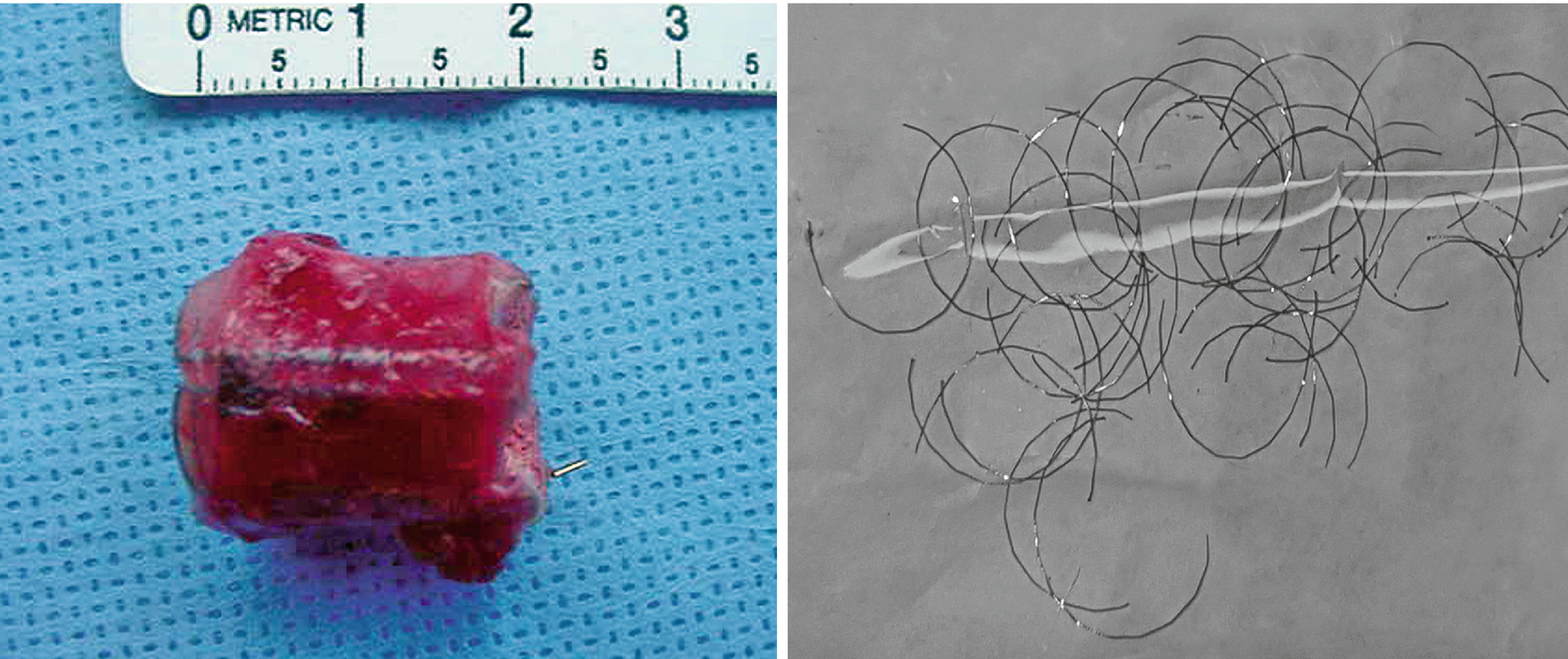

While endoscopic removal of a prostatic urethral stent can be feasible and safe with use of a holmium laser [21], open stent explantation with urethral reconstruction for a failed urethral stent is frequently necessary and is always challenging [5, 22]. Severe polypoid hyperplasia and inflammatory infiltrate, the histological changes associated with long-term urethral stents, discourage endoscopic removal in most cases [23]. Endoscopic stent removal wire by wire is possible after transurethral stent cutting [9]. However, an open en-bloc removal of the scarred urethra together with the entrapped stent has been the preferred choice in cases requiring a more definite reconstruction [5].

The thermo-expandable Memokath stent was designed for easy implantation and removal from urethra. However, being often left in place for 6–12mo before removal, it is not devoid of encrustation and recurrent stricture. This treatment should be considered as a temporary option, and should not be used in patients who are fit for urethroplasty [13, 24, 25]. Additionally, a recent report has shown good results after urethroplasty in patients with previous Memokath stent, and could contribute to a further argument discouraging temporary stenting in patients willing to undergo a definite reconstruction [14].

27.3 Management of Re-Stricture after Urethral Stent Use

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree