29 Upper limb contouring

Synopsis

Upper limb contour is often of great concern to individuals following weight loss.

Upper limb contour is often of great concern to individuals following weight loss.

Correction of contour deformities of the axilla and forearm and in some instances the lateral thoracic region as well as the arm are critical to maximizing the aesthetics of the upper extremity.

Correction of contour deformities of the axilla and forearm and in some instances the lateral thoracic region as well as the arm are critical to maximizing the aesthetics of the upper extremity.

Liposuction often plays an important role in brachioplasty.

Liposuction often plays an important role in brachioplasty.

Scar placement is an important element of upper extremity contouring.

Scar placement is an important element of upper extremity contouring.

Upper limb contouring is associated with few serious complications.

Upper limb contouring is associated with few serious complications.

Introduction

The rapid growth in bariatric surgery over the last decade has led to an increase in demand for surgical procedures to address the contour deformities of the arm following weight loss. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, from 2000 to 2008, there has been a 4059% increase in the number of brachioplasty procedures performed in the US.1 While weight loss affects the entire body, for some individuals the arms are often of greatest concern because of their visibility in everyday activities. The combination of a patient desire for improved aesthetics of the upper limb and the ready visibility of the arms in routine activities creates a special challenge for plastic surgeons considering upper limb contouring.

Historical perspective

Prior to the year 2000, brachioplasty procedures were rarely performed by most plastic surgeons. The earliest descriptions of brachioplasty were relatively simple techniques involving the removal of an ellipse of soft tissue. The axilla was not addressed and candidates for surgery were usually moderately overweight individuals.2–4 In the 1970s multiple articles were published that described different patterns of arm soft-tissue excision. Several of these publications included techniques to avoid scar contracture at the arm/axilla transition.5–8 Pitanguy8 specifically described addressing deformities of the axilla and lateral thoracic region along with the arm. The first case report of a massive weight loss patient undergoing brachioplasty was published in this period.9 In the 1980s, techniques were described to perform brachioplasty as part of an upper body lift and near-total body lift and Goddio reported on an innovative technique of burying soft-tissue excess.10–12

Brachioplasty continued to evolve in the 1990s.13,14 Liposuction became a more integral component of these procedures and Lockwood13 proposed that the posteromedial soft tissue of the arm be suspended to the clavipectural periosteum by means of the clavipectoral fascia and axillary fasciae. He argued that, when these structures loosen, they lead to a “loose hammock“ effect or arm ptosis. Lockwood’s technique for brachioplasty described securing the arm flap to the axillary fascia and the incorporation of a superficial fascial system repair of incisions to help reduce the incidence of wide scars and unnatural contours.

In the last decade, numerous articles have been written on brachioplasty. In an effort to minimize scar length, several authors have described excisional techniques limited to the axilla and proximal arm in combination with liposuction.15–17 The majority of recent articles and symposia on brachioplasty have involved almost exclusively the weight loss patient and the size of the series analyzed has increased considerably from a decade ago.18–28 Much of the discussion today in the literature is on scar position, the timing and use of liposuction, and the incorporation of short scar techniques in the management of the postbariatric patient.

Basic science/disease process

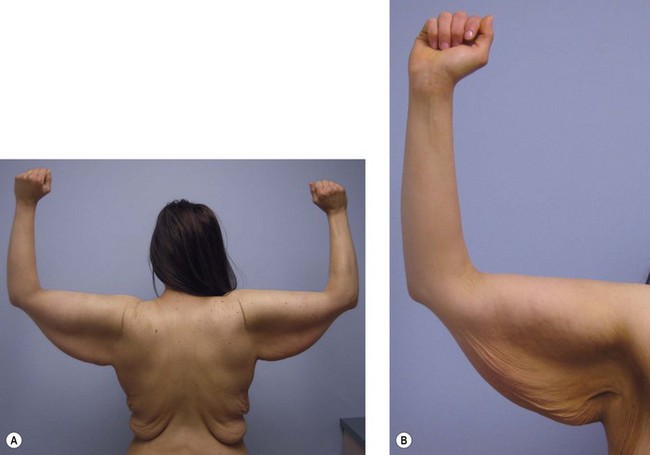

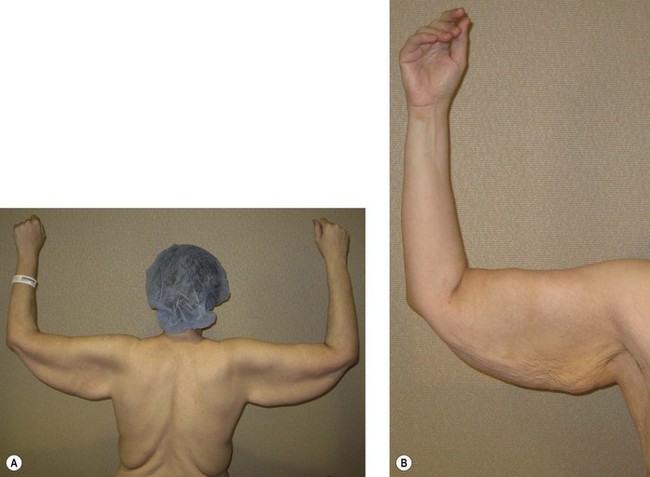

The arm deformity associated with weight loss is often dramatic and is influenced by multiple factors, including patient body mass index (BMI), highest BMI ever obtained, change in BMI, age, and sex (Figs 29.1–29.5). In the morbidly obese individual, fat deposits are usually most prominent along the axilla, anterior, posterior and medial arm (Fig. 29.1). With weight loss, these regions of the upper extremity manifest the greatest excess in soft tissue. Patients presenting at a lower BMI and particularly those who had reached a very high BMI prior to weight loss are likely to have more soft excess than an individual who has had smaller change in weight (Figs 29.2 and 29.3). Patients in their fifth decade and beyond, particularly women, perhaps because of attenuated connective tissue, often present with large amounts of excess tissue despite relatively small changes in BMI (Fig. 29.4). Men tend to have the majority of their deformity limited to the proximal arm and axilla (Fig. 29.5). Women may have this appearance as well, but are more likely to have a deformity extending to the elbow and forearm (Fig. 29.4).

Diagnosis/patient presentation

The average age in our postbariatric population is 39.29 Most of these individuals are very active and eager to minimize time off work and time away from family obligations. It is therefore quite common for a patient who expresses concerns about multiple areas of the body to request that all areas be addressed as soon as possible. One of the most important components of patient assessment is determining in what order and with what other procedures a brachioplasty should be performed. The patient’s goals should be carefully considered in formulating a plan. With regard to the arm specifically, it is important to gain a clear understanding from patients of their tolerance for scars and of the degree of contour improvement they are expecting. A postbariatric patient anticipating an optimum result from a limited procedure in the proximal arm is likely to be disappointed.

Patient selection

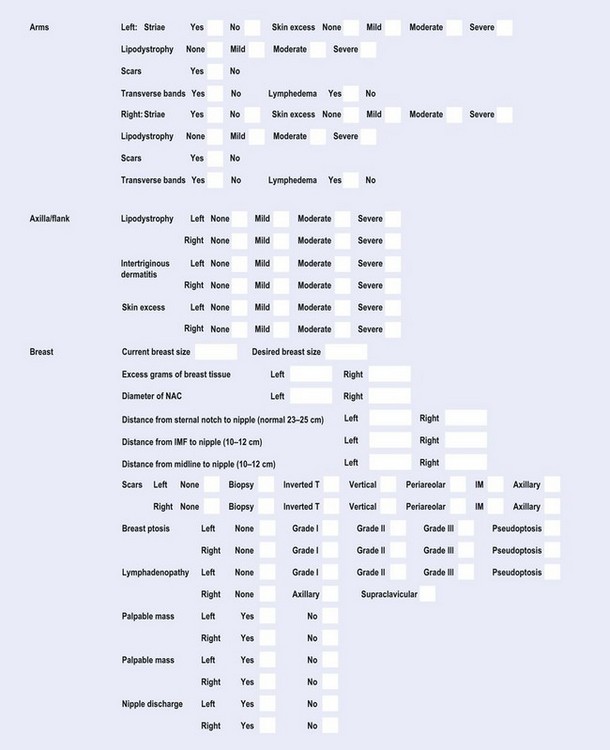

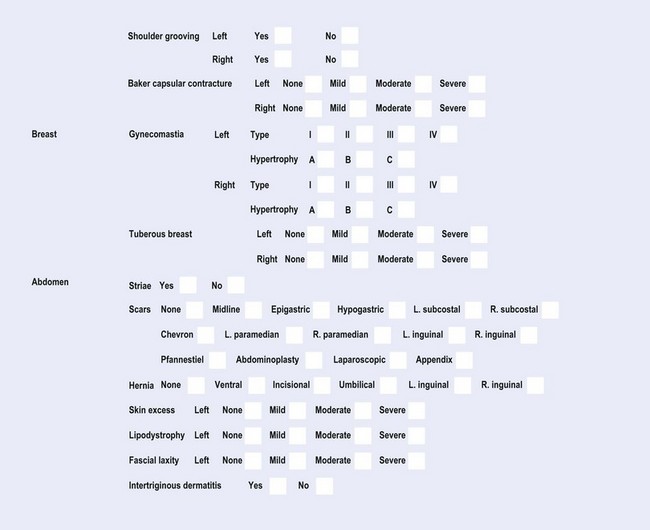

Examination of the postbariatric brachioplasty candidate should be thorough, with particular attention directed toward the upper body. Along with the degree of soft-tissue excess present along the forearm, arm, and axilla, an assessment should be made of the breasts, lateral thoracic region, and back. The fat content of all these areas should be noted. A standardized exam form is helpful (Fig. 29.6). Notation is made as to whether intertriginous dermatitis is present, potentially along the axilla. Lymphedema and/or stigmata of lymphedema should be documented, as should the presence of arterial or vascular insufficiency. Existing scars, transverse arm bands, and striae along the upper extremity should be noted.

Plan formulation

The information gathered from the patient history and physical exam is instrumental in formulating a preliminary plan. For patients expressing concerns only about their arms, the plan is clear. For these patients, it is important to clarify the importance of addressing the axilla in rejuvenating the arm. Following massive weight loss, most patients express concerns about more than just their arms; usually the breasts, lateral thoracic region, back, abdomen, thighs, and buttocks are of issue as well. The options available to the plastic surgeon are multiple. Our preference is to perform a body lift first, as a single procedure, and then to follow with a combination mastopexy/lateral thoracoplasty/brachioplasty not before 3 months.30 A medial thigh lift, if necessary, would take place at least 3 months later. Our rationale for this sequence and combination of procedures derives from the observation that the body lift procedure greatly affects the rolls frequently present along the upper and lower back. In the vast majority of patients, any remaining rolls along the back and flanks following a body lift can then be addressed by the combination mastopexy/lateral thoracoplasty/brachioplasty.

Before being considered for any procedure, certain criteria must be met and issues addressed. The patient should be at a stable weight for at least several months. This will vary depending on bariatric procedure. Operating during a period of active weight loss may result in an early recurrence of soft-tissue laxity and, from a safety perspective, the patient is unlikely to be nutritionally and metabolically optimized. Patients with symptoms suggestive of problems related to bariatric surgery should be evaluated by their surgeon. Individuals with a history of major mental illness or acute mental illness are asked to be evaluated by an appropriate health professional. Patients are advised to maintain the supplemental regimen prescribed by their bariatric surgeon. Individuals with a history of tobacco consumption are urged to stop as soon as possible. The risks of tobacco, including impared wound healing and thromboembolic phenomena, are clearly established in the literature and are relayed to the patient.29,31 My preference is for patients who are on medications for weight loss, to stop them. All patients are referred for medical clearance. While weight loss dramatically improves the health of morbidly obese individuals, not all conditions are eliminated.32 A careful medical evaluation of health is imperative.