Understanding the Fascial Supporting Network of the Breast: Key Ligamentous Structures in Breast Augmentation and a Proposed System of Nomenclature

Simone A. Matousek, F.R.A.C.S.

Russell J. Corlett, F.R.A.C.S.

Mark W. Ashton, F.R.A.C.S.

Potts Point, New South Wales, Australia

From Taylor Laboratory, Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience, University of Melbourne, Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Received for publication April 6, 2013; accepted August 16, 2013.

Copyright © 2014 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons

DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000436798.20047.dc

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Background: The fascial system of the breast has, to date, only been described in general terms. This anatomical study has developed two distinct methods for better defining existing breast structures such as the inframammary fold, as well as defining previously unnamed ligamentous structures.

Methods: The authors harvested and examined 40 frozen, entire chest wall cadavers. Initially, 15 embalmed cadavers were studied with a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, which proved to be inaccurate. A further 20 fresh and five embalmed chest walls were harvested, frozen, and then sectioned with a bandsaw (3-cm slices) and knife (1.5- to 4-cm slices) depending on the area studied. Sagittal, horizontal, and oblique sections along the length of the ribs were created and then dissolved using either sodium hydroxide or alcohol dehydration followed by xylene immersion. Constant fascial connections between the breast parenchyma, superficial fascia, pectoralis muscle (deep) fascia, and bone were observed.

Results: Specimens clearly demonstrated internal structures responsible for the surface landmarks of the breast. The precise configuration of the infra mammary fold was clearly visible, and new ligamentous structures were identified and named.

Conclusions: Knowing the location and interrelationship of these structures is particularly important in breast augmentation. Reappraisal of the anatomy in this area has enabled precise identification of ligamentous structures in the breast. Correlation of the findings in this article to specific clinical conditions or modes of treatment can be proven only by a clinical series that scientifically addresses the necessity and efficacy of preserving, releasing, or repositioning any of these structures. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 133: 273, 2014.)

Various methods have been used to study the ligamentous anatomy of the breast. Until now, many of these methods have produced conflicting results, possibly because of dissection artifact. With advancing breast implant technology and expansion of its role in the treatment of breast deformity, a concomitant need exists for a more detailed anatomical knowledge of the fascial and ligamentous structure of the breast. We describe two new methods to study the breast fascial system. These provide a more accurate assessment over existing techniques.

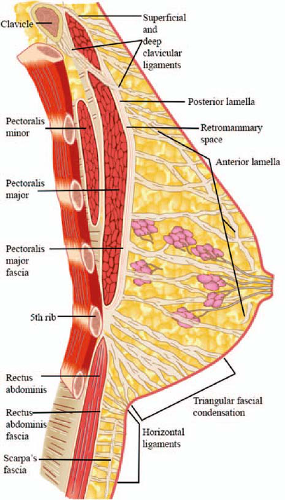

According to classic anatomic descriptions, the base of the nonptotic breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle between the second and sixth ribs.1

The breast overlies the fascia investing the chest wall musculature—most significantly, the pectoralis major muscle, the rectus abdominis muscle inferomedially, serratus anterior superolaterally, and a small portion of the external oblique inferolaterally.

The gland is anchored to the pectoralis major fascia by the suspensory ligaments first described by Astley Cooper in 1840.2 These ligaments run throughout the breast tissue parenchyma from the deep fascia beneath the breast and attach to the dermis of the skin.

Overlying this is the superficial fascial system of the breast, first described by Scarpa3 and Colles4 and then further defined by Lockwood.5 It is continuous with the superficial fascial system of the trunk and is best described as a connective tissue network extending from the subdermal plane to encase the fat and lobular tissues of the breast. This superficial fascial network has posterior extensions connecting it to the fascia overlying the muscles of the chest wall and, in certain regions, to the periosteum. Anteriorly, it has more numerous extensions, where it is inserted into the dermis.

While this superficial fascial system has been studied in the literature, there is a paucity of fine detail regarding its anatomical structure, particularly in the lower pole and inframammary fold. In addition, some of the studies directly conflict with each other, and some describe structures, such as the horizontal septum, that are not mentioned elsewhere.

We aimed to develop techniques that allow a more detailed study of the breast’s fascial system. In particular, we aimed to provide specific information about the fascial structures that constitute the lower pole and inframammary fold and the interrelationship between these structures and other elements of the breast, particularly the suspensory ligaments of Astley Cooper and the superficial fascial system of Scarpa.

Materials and Methods

We dissected 40 female cadavers using different approaches to define the ligamentous anatomy of the breast. All cadavers ranged in age from 58 to 95 years, with an average age of 83 years. We examined a broad range of breast sizes from those with hypoplasia or involution to overweight specimens with significant ptosis.

We initially studied 15 embalmed cadavers with a combination of blunt and sharp dissection to define key structures. This was, however, as previously stated, limited by dissection artifact.

A further 20 fresh and five embalmed female chest walls were harvested from whole cadavers from the midsternum to the posterior axillary line. The chest walls were then frozen and fixed with needles to maintain the correct position of the inframammary fold. Sections were obtained either with a bandsaw (3 cm wide) or a knife (1.5 to 4 cm wide, depending on the area studied, which allowed for greater precision).

We obtained a more accurate demonstration of the fascial network with sagittal (18), horizontal (five), and oblique (two specimens along the length of the ribs in the intercostal spaces) sectioning, and correlated the results from the different sections.

In 15 specimens, we used a gradual fat dissolution technique using four subsequent treatments with 10% sodium hydroxide and washing with water to demonstrate the fascial network. This gradual removal of fat maintains the fascial structure and allows for better definition of the ligaments of the breast. Constant fascial connections among the breast parenchyma, superficial fascia, pectoralis muscle (deep) fascia, and bone were examined.

In 10 specimens, we used a different dissolution technique. This involved using absolute ethanol baths with increasing concentrations of 50%, 75%, and 100% for 24 hours, followed by immersion in xylene for several days (the immersion time depended on the fat content of the specimen). This accurately demonstrated bony attachments of the ligamentous network.

Results

Although the superficial fascial system varies according to age, degree of ptosis, and adiposity, we observed specific recurring ligamentous patterns in the cadavers we studied. As expected, fascial quality deteriorated with increasing age of the specimens; there was a greater degree of ptosis and ligaments were more lax and less dense in older specimens. However, the configuration of the structures was the same across all ages.

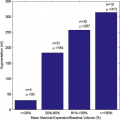

The anterior breast capsule (or superficial layer of the breast fascia) is well defined to the level of the fourth rib, after which it becomes obscured by glandular tissue and ducts as they form the nipple-areola complex. It is not visible inferior to the fourth intercostal space, because it gives way to direct dermal insertions, which fan out from the fifth rib and pectoral fascia superior to it. The posterior breast capsule creates a gliding plane between the pectoral fascia and breast, which is called the retromammary space (Fig. 1).

Commencing medially with the parasternal area, there are many dense transverse connections between the periosteum of the sternum and dermis, which firmly anchor the fused superficial and deep fascial system in this region. These medial sternal ligaments are short, run horizontally along the length of the sternum, and are stronger and thicker than in the remainder of the

breast because there is little fat and no glandular tissue interspersed in this region. This creates a very firm zone of adherence medially (Fig. 2).

breast because there is little fat and no glandular tissue interspersed in this region. This creates a very firm zone of adherence medially (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Diagram of a sagittal section through the nipple, demonstrating the anterior and posterior breast capsule, ligaments, and triangular fascial condensation. |

As the pectoralis major muscle takes its origin from the sternum and the first to fifth ribs, these ligaments extending from the pectoral fascia through to the anterior breast capsule and dermis gradually become longer, especially in the retroareolar portion of the ptotic, larger breast. This region has the greatest amount of glandular tissue and fat. The ratio of fat to glandular tissue varies greatly when comparing different breasts. With greater degrees of fatty infiltration in this area, the ligaments are more stretched, resulting in a greater degree of ptosis.

Superiorly, two direct bony anchor points to the clavicle were observed: one superior to its superficial aspect through the pectoral fascia (superficial clavicular ligament) and one to the deep inferior aspect of the clavicle through the fascial septum between the clavicular and sternal heads of the pectoralis major muscle (deep clavicular ligament). These are direct insertions between periosteum and dermis without intervening anterior breast capsule, which commences inferior to these attachments at the level of the second rib.

There is a fascial thickening between the pectoral fascia and superolateral breast at the lateral aspect of the pectoralis major as its fibers converge to form its tendinous insertion to the humerus, the lateral pectoralis major ligament (Fig. 3). This is a firm superolateral anchor point for the breast.

In the inferior pole of the breast, the ligaments run obliquely and inferiorly to insert directly into the dermis, with no intervening anterior breast capsule. At the level of the fifth rib, they fan out in a triangular fashion from a well-defined bony attachment where they are fused to the periosteum of the superior aspect of the fifth rib (the apex of the triangle) in the intermuscular septum between the rectus abdominis and pectoralis major. The most inferior of these fibers insert into the dermis of the inframammary fold. The remaining superior fibers insert into the inferior pole of the breast. This forms what we have named the triangular fascial condensation (Figs. 4 and 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree