Ultrasound-guided Breast Percutaneous Needle Biopsy

Richard E. Fine

The number of biopsies required for diagnosis of image-detected abnormalities has increased with the continued promotion of screening for the early detection of breast cancer. In fact, each year in the United States, women undergo approximately 1.8 million breast biopsies. As confirmed by the 2005 International Consensus Conference II on diagnosis and treatment of image-detected breast cancer, minimally invasive image-guided percutaneous breast biopsy should be the first-line intervention for both palpable and nonpalpable image-detected abnormalities. Being less invasive and more cost-effective, image-guided percutaneous breast biopsy has essentially eliminated the need for open surgical biopsy for diagnosis, without sacrificing accuracy. Patients diagnosed with breast cancer by image-guided percutaneous biopsy may then proceed to definitive surgical management or be monitored with appropriate imaging and clinical follow-up if their pathology is benign.

Many of the early concerns about instituting an image-guided breast biopsy program such as patient acceptance (sampling rather than excision), accuracy (false-negative rate), overutilization (maintenance of proper indications), and qualifications (performed by radiologists or surgeons) have been resolved. The vast majority of patients with breast cancers and benign breast lesions will have their diagnosis made accurately with percutaneous image-guided needle biopsy, with many of these with ultrasound guidance.

Almost any patient with an indeterminate, image-detected lesion, palpable or nonpalpable, should undergo a minimally invasive image-guided percutaneous biopsy. The modalities for image guidance include ultrasound, stereotactic, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) guidance. These abnormalities fall into the following categories established by the ACR (American College of Radiology) BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) lexicon:

BI-RADS 5—highly suspicious abnormalities; biopsy provides a histology diagnosis for preoperative patient consultation

BI-RADS 4—indeterminate abnormalities; require biopsy and may avoid a trip to the operating room for an abnormality with perhaps only a 20% risk of malignancy

BI-RADS 3—(probably benign, 2%–4% risk of malignancy); abnormalities identified in a patient with a strong family history, difficult clinical and imaging examination, or a patient with a high level of anxiety.

The choice of image guidance is dependent on the modality of detection, the lesion type, and the tissue density of the breast parenchyma. The most common indication for ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy is the indeterminate or suspicious, ultrasound-visible, solid mass. However, some solid masses are better visualized on mammography because of a large fatty replaced breast parenchyma in which stereotactic guidance would be preferable. The usual approach for the patient with mammogram-detected microcalcifications without a mass is with stereotactic-guided percutaneous needle biopsy. However, rarely, with the advent of high-end, high-resolution ultrasound equipment, a prominent cluster of indeterminate calcifications can be biopsied with ultrasound guidance. Performing a second-look, directed ultrasound on a patient with an MRI-detected enhancing mass lesion will identify a lesion amenable to ultrasound guidance approximately 60% of the time. The advantage of ultrasound guidance over other imaging modalities includes patient comfort, lying supine (as opposed to prone with neck extension on the stereotactic table), and availability of ultrasound as an office-based procedure minimizing costs and scheduling delays.

The presence of a nonpalpable, solid mass is an indication for an ultrasound-guided needle core biopsy to obtain a histology diagnosis. It is also appropriate to utilize ultrasound guidance for the solid, palpable mass according to the American Society of Breast Surgeons Position Statement on Image-guided Percutaneous Biopsy of Palpable Breast Lesions (January 29, 2001). Without the adjunct of image guidance, the surgeon would be unable to confirm the proper penetration of the core needle through the lesion or the alignment of the tissue-sampling portion of a vacuum-assisted or rotating core device, leading to false-negative results.

The surgeon should categorize these abnormalities on the basis of their risk of malignancy. Smooth, well-defined margins suggest that a lesion is benign, whereas irregular, indistinct margins suggest malignancy. Heterogeneous internal echo pattern implies malignancy, whereas benign lesions usually display homogeneity. Posterior enhancement represents transmission of sound through the lesion related to lesion homogeneity and causes a brighter echo pattern behind the lesion, which is usually benign. The heterogeneous nature of many cancers will cause haphazard sound refraction, which leads to irregular shadowing. However, bilateral edge shadows are consistent with a smooth-walled benign lesion. Finally, benign lesions tend to be wider than they are tall (width greater than anterior–posterior diameter). In contrast, cancers tend to disrupt the adjacent normal tissue planes and appear taller than they are wide. Familiarity of these characteristics will help the surgeon anticipate the diagnosis. Any discordance between the image analysis and the pathology results would require excision of the lesion.

Unless the surgeon’s assessment of the lesion finds all characteristics falling strictly in the benign category, they would categorize the lesion as indeterminate and some type of intervention is required. A smooth, well-circumscribed, anechoic lesion with bilateral edge shadowing and posterior enhancement representing a simple cyst, which is also asymptomatic, would require no intervention. For the small (less than 1 cm) solid, hypoechoic lesion with smooth margins, a homogeneous internal echo pattern and ellipsoid shape, ultrasound-guided needle biopsy can confirm a benign diagnosis, but a surgeon with experience in ultrasound interpretation and pathologic correlation may choose to monitor the lesion, especially with a highly compliant patient (Fig. 3.1A, and 3.1B).

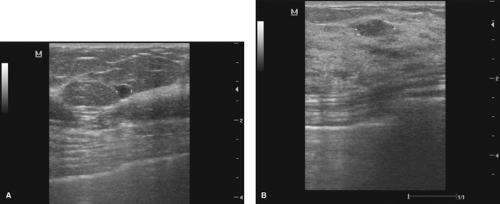

“Indeterminate-risk” lesions often have heterogeneous interiors, indistinct yet smooth margins, and they may have a lateral/anterior–posterior dimension ratio greater than 1. If a surgeon cannot characterize a lesion as a simple cyst, aspiration to distinguish a complex cyst from a solid mass is required. A lesion with a mixed internal echo

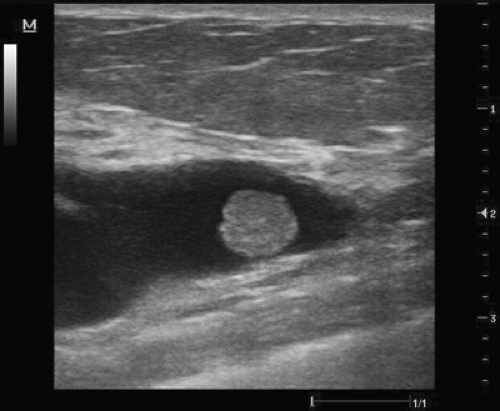

pattern and posterior enhancement suggests the presence of fluid versus a solid lesion and an aspiration may be preferable prior to a core biopsy (Fig. 3.2). Chapter 2 addresses the details of cyst aspiration. Another indeterminate lesion requiring intervention is the cystic appearing abnormality with a mural or solid-appearing component. Only resolution of a complex cyst or a specific benign diagnosis on percutaneous needle biopsy will avoid surgical excision (Fig. 3.3).

pattern and posterior enhancement suggests the presence of fluid versus a solid lesion and an aspiration may be preferable prior to a core biopsy (Fig. 3.2). Chapter 2 addresses the details of cyst aspiration. Another indeterminate lesion requiring intervention is the cystic appearing abnormality with a mural or solid-appearing component. Only resolution of a complex cyst or a specific benign diagnosis on percutaneous needle biopsy will avoid surgical excision (Fig. 3.3).

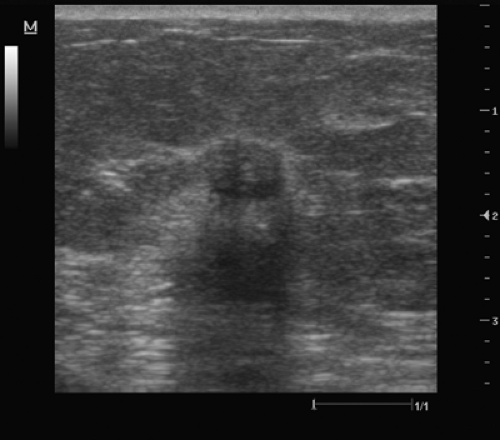

Higher risk of malignancy requires a pathology diagnosis. For the more suspicious, high-risk lesions with jagged edges, nonhomogeneous internal echo patterns and irregular shadowing, the malignant diagnosis obtained with ultrasound-guided biopsy in a cost-effective, efficient manner in the office setting, facilitates planning of the definitive management (Fig. 3.4).

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy of highly suspicious (BI-RADS 5) lesions is optimal for planning the management of malignant lesions. Confirmation of the

histology eliminates an initial operating room procedure for diagnosis or a return to the operating room for contaminated resection margins. Encountering positive margins is twice as frequent at definitive surgery if not preceded by an image-guided percutaneous biopsy to confirm the malignant diagnosis. Patients who may be candidates for neoadjuvant or preoperative chemotherapy will ideally be diagnosed with image-directed percutaneous biopsy. The needle core biopsy tissue provides many of the ancillary markers required for appropriate management (estrogen/progesterone receptors and Her-2 neu).

histology eliminates an initial operating room procedure for diagnosis or a return to the operating room for contaminated resection margins. Encountering positive margins is twice as frequent at definitive surgery if not preceded by an image-guided percutaneous biopsy to confirm the malignant diagnosis. Patients who may be candidates for neoadjuvant or preoperative chemotherapy will ideally be diagnosed with image-directed percutaneous biopsy. The needle core biopsy tissue provides many of the ancillary markers required for appropriate management (estrogen/progesterone receptors and Her-2 neu).

Figure 3.2 This lesion exhibits a mixed internal echo pattern and posterior enhancement, and although thought to be a solid lesion, it may prove to be a complex cyst on aspiration attempt. |

Figure 3.3 This lesion has both benign and indeterminate characteristics. The lesion is smooth but has a heterogeneous internal echo pattern and questionable shadowing. |

The most common indication for an ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy is the indeterminate solid mass (BI-RADS 4), where approximately 80% will have a benign diagnosis. The previous standard for diagnosis of image-detected abnormalities with open surgical biopsy had several disadvantages including

anesthesia requirements often resulting in time loss from work not only for the patient but also for the provider of needed transportation;

the separate, time-consuming trip to the radiology suite for lesion localization, adding to the discomfort and emotional stress;

Figure 3.5 Dilated, subareolar duct with an intraductal solid lesion suggestive of an intraductal papilloma.

larger incisions/scars, including scars within the parenchyma, leading to alterations on future mammograms; and

potentially deforming surgery to remove a benign lesion that did not require removal.

If the benign pathology diagnosed with ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy fully explains the imaged findings, the surgeon need not remove the lesion, whether palpable or nonpalpable. The patient must also be comfortable with the reassurance of a benign diagnosis without removal of the suspect lesion. An image-guided percutaneous biopsy would be inadvisable for the patient who desires complete removal of the lesion, especially when it is palpable. The surgeon should avoid a percutaneous image-guided biopsy if surgical excision of a target lesion were part of the definitive management because the suspected pathology result would not be acceptable without excision. An example would be subareolar lesions with or without associated nipple discharge that are suspicious for papillary lesions where the pathologist requires intact histology architecture to eliminate atypia or papillary carcinoma (Fig. 3.5).

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous excision is an alternative to open surgical excision for those patients who desire the removal of their lesions, especially when palpable, despite being well informed. The surgeon may accomplish percutaneous excision with either one of the vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) devices or one of the devices capable of removing a large, single intact core of tissue. The procedure may be both therapeutic and diagnostic in a single setting. Percutaneous management of benign lesions has several benefits. In addition to the previously discussed disadvantages of the surgical approach, the patient avoids the physical and emotional trauma and added cost. Further indications for percutaneous excision with ultrasound guidance include but are not limited to the following:

Nonoperative potential therapy for benign lesions

Remove image evidence and or palpability of the lesion

Clinically apparent fibroadenomas in younger patients

Palpable lipoma causing location-related discomfort (inframammary fold)

Nonoperative potential therapy for malignant lesions;

Highly suspicious masses or densities

Lesions ≤1.5 cm with large intact sampling devices

The initial step, prior to ultrasound-guided breast biopsy, is to take an appropriate history, which includes an assessment of risk factors for breast cancer, and perform a clinical breast examination. A knowledge of anticoagulant medications can prevent

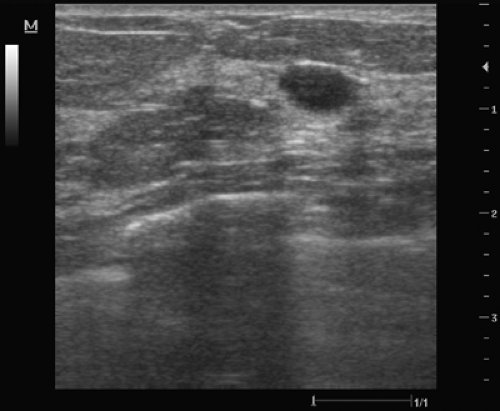

bleeding complications, including significant hematomas. A significant risk profile might lead the surgeon to perform an image-guided percutaneous biopsy on a lesion of low malignant potential (BI-RADS 3). The physician responsible for performing the biopsy should perform a clinical breast examination, confirming correlation between any suspicious palpable mass detected and the image-detected abnormality. The physician should also reevaluate the diagnostic ultrasound examination in complement to additional imaging available such as mammogram or MRI. Careful evaluation of the diagnostic ultrasound performed at an outside institution may suggest lesion characteristics, such as posterior enhancement, that allows the physician to attempt a cyst aspiration and eliminate the unnecessary wasting of an expensive disposable biopsy tool for a presumed solid lesion (Fig. 3.6).

bleeding complications, including significant hematomas. A significant risk profile might lead the surgeon to perform an image-guided percutaneous biopsy on a lesion of low malignant potential (BI-RADS 3). The physician responsible for performing the biopsy should perform a clinical breast examination, confirming correlation between any suspicious palpable mass detected and the image-detected abnormality. The physician should also reevaluate the diagnostic ultrasound examination in complement to additional imaging available such as mammogram or MRI. Careful evaluation of the diagnostic ultrasound performed at an outside institution may suggest lesion characteristics, such as posterior enhancement, that allows the physician to attempt a cyst aspiration and eliminate the unnecessary wasting of an expensive disposable biopsy tool for a presumed solid lesion (Fig. 3.6).

Figure 3.6 The posterior enhancement seen with this presumed solid, benign-appearing lesion suggests the possibility of complex cystic fluid that may be aspirated before attempting a core biopsy. |

The surgeon should outline the details of the benefits and risks of an ultrasound-guided percutaneous breast biopsy and have the patient sign an appropriate consent. Specific to the image-guided percutaneous procedures, the physician should emphasize to the patient that this is diagnostic procedure and that further intervention, including surgical excision may be necessary, depending on the concordance between the pathology and the impression of the ultrasound. It is important that the patient understands that unless the surgeon specifically plans a percutaneous excision, the mass may remain on future imaging and continue to be palpable. With ultrasound-guided percutaneous excision, it should be pointed out that a small percentage of lesions either will not be successfully removed in their entirety or will again be visualized on the follow-up imaging studies.

Positioning

The success of an ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy begins with proper positioning of the patient, physician, and equipment. The physician may place a pillow under the shoulder, with the ipsilateral arm raised to optimize the patient’s supine position. This allows the breast to disperse more evenly on the chest wall, eliminating some of the thickness of the breast parenchyma. In addition, the lateral decubitus patient position provides the surgeon with access to deeper or posterior lesions by keeping the biopsy device parallel with the pectoral muscle. Placement of the equipment in the procedure room enhances the physician’s visualization and comfort. By placing the ultrasound unit on the opposite side of the patient, the physician prevents turning his/her head away from the biopsy field to see the ultrasound monitor, further adding to the comfort. The physician’s best visualization of the advancing biopsy device is along a

straight line of sight between the physician’s vision, the physician’s arm, down the length of the biopsy device, along the long axis of the ultrasound transducer, and up to the ultrasound monitor (Fig. 3.7).

straight line of sight between the physician’s vision, the physician’s arm, down the length of the biopsy device, along the long axis of the ultrasound transducer, and up to the ultrasound monitor (Fig. 3.7).

Optimizing the Ultrasound Image and Scanning Technique

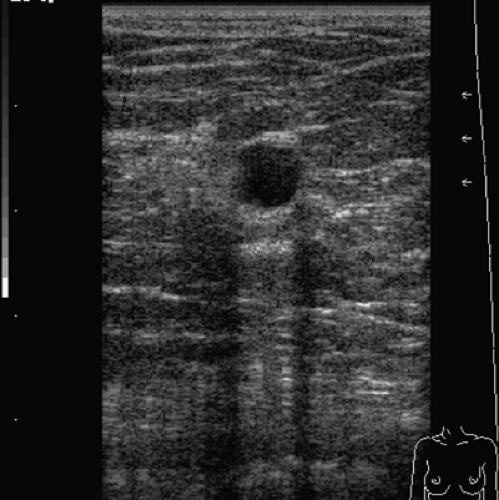

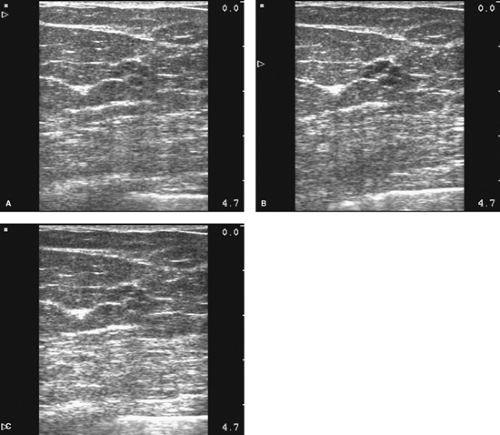

The ability to perform a successful ultrasound-guided percutaneous breast biopsy is also dependent on the ultrasound image quality and the physician’s ultrasound scanning skill. The appropriate overall gain and time-gain-compensation slope should provide a uniform grayscale throughout the image. An improper overall gain setting may alter the appearance of the internal echo pattern and limit the ability to distinguish solid from cystic lesions. To achieve the optimal lateral resolution, the physician must align the focal zone with the target lesion. This will better illustrate the retrotumoral characteristics such as posterior enhancement (Fig. 3.8A–C). Once properly visualized, the physician compares the target lesion with the original ultrasound images and then documented, labeled, and measured.

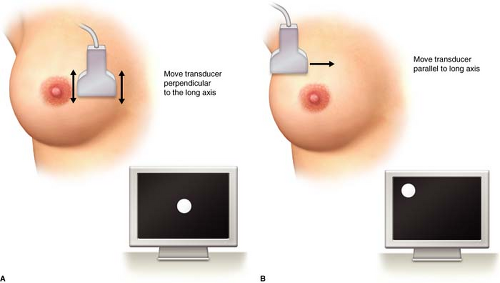

The physician performing the biopsy should be facile with two basic scanning techniques that are crucial for identifying the area of greatest lesion diameter and positioning the lesion on the ultrasound monitor to limit the skin to lesion distance. Movement of the transducer in a motion perpendicular to the long axis of the transducer allows the scanner to visualize the lesion from end to end and find the widest portion of the lesion. Sliding the transducer in the direction parallel with the long axis will change the position of the lesion on the ultrasound monitor (Fig. 3.9A and 3.9B). To avoid veering off the edge of the lesion, the physician should position the ultrasound transducer so that the greatest diameter of the lesion is within the ultrasound plane, preventing missing the lesion with the needle core biopsy device. By correctly positioning the lesion on the ultrasound monitor, the physician will traverse the least amount of breast tissue with the biopsy device.

Biopsy Devices

The physician performing the ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy must decide on the proper device or instrument that best accomplishes the goal of the procedure. The most common objective of any image-guided biopsy procedure is of course to obtain a

benign or malignant diagnosis but the patient’s desire or clinical presentation may influence the physician. The tools for specimen acquisition have evolved from fine-needle aspiration (FNA), automated Tru-cut (ATC) core needle, vacuum-assisted core biopsy devices to large-core, intact sample instruments, providing either “sampling” capability, adequate for most lesions or “removal” (by percutaneous excisional biopsy) capability for selected lesions. The surgeon must select the most appropriate instrumentation and biopsy type for each case.

benign or malignant diagnosis but the patient’s desire or clinical presentation may influence the physician. The tools for specimen acquisition have evolved from fine-needle aspiration (FNA), automated Tru-cut (ATC) core needle, vacuum-assisted core biopsy devices to large-core, intact sample instruments, providing either “sampling” capability, adequate for most lesions or “removal” (by percutaneous excisional biopsy) capability for selected lesions. The surgeon must select the most appropriate instrumentation and biopsy type for each case.

Figure 3.8 The focal zone is appropriately set to optimize lateral resolution in B, whereas the focal zone is too high in A and the focal zone is too low in C. |

Figure 3.10 An ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of an intramammary lymph node with an inset illustrating the visualization of the needle within the lesion. |

Despite the criticism related to the degree of insufficient sampling and the need for expert cytopathology, FNA biopsy is a quick, inexpensive technique to delineate benign from malignant solid breast masses. Unfortunately, even with specialized experience and expertise, FNA yields inferior false-negative diagnosis rates for primary breast cancer compared to those obtained with core biopsy. However, ultrasound-guided FNA is ideally suited to evaluate lesions in areas where more invasive biopsy devices may be difficult, dangerous, such as the axilla, or adjacent to a breast implant. The diagnosis of lymph node metastasis by FNA can assist with pre-operative staging in consideration of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy or eliminate sentinel lymph node biopsy by confirming positive cytology in clinically suspicious lymph nodes (Fig. 3.10).

The use of ATC needle core biopsy (Fig. 3.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree