16 Tumors of the lips, oral cavity, oropharynx, and mandible

Synopsis

Cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx is thought to be caused by accumulated genetic alteration initiated by toxins from tobacco and promoted in the United States by alcohol intake.

Cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx is thought to be caused by accumulated genetic alteration initiated by toxins from tobacco and promoted in the United States by alcohol intake.

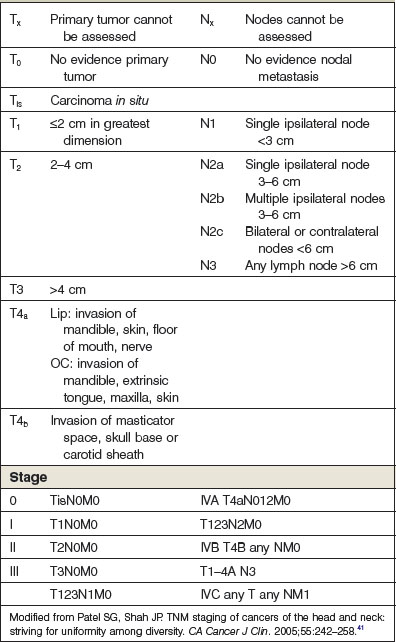

Tumors are staged according to the TNM system that considers anatomic subsite in the upper aerodigestive tract, size and adjacent extension for the primary tumor (T) number and laterality of cervical lymph nodes (N) and presence or absence of distant metastases (M).

Tumors are staged according to the TNM system that considers anatomic subsite in the upper aerodigestive tract, size and adjacent extension for the primary tumor (T) number and laterality of cervical lymph nodes (N) and presence or absence of distant metastases (M).

Surgery or radiotherapy are both effective in early stage tumors but surgery followed by postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy is preferable in Stage III or above tumors.

Surgery or radiotherapy are both effective in early stage tumors but surgery followed by postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy is preferable in Stage III or above tumors.

The primary site and the cervical metastases or in some cases micrometastases are treated together as a composite resection or resection of the primary and neck dissection.

The primary site and the cervical metastases or in some cases micrometastases are treated together as a composite resection or resection of the primary and neck dissection.

Because of the anatomical complexity of the area, surgery and radiotherapy often interfere with the critical functions of respiration and alimentation. Resection and reconstruction should be designed to completely remove the cancer and preserve or restore as much function as possible.

Because of the anatomical complexity of the area, surgery and radiotherapy often interfere with the critical functions of respiration and alimentation. Resection and reconstruction should be designed to completely remove the cancer and preserve or restore as much function as possible.

Extensive surgery with or without previous radiotherapy may result in difficult and dangerous complications such as osteoradionecrosis, fistula, carotid exposure and hemorrhage.

Extensive surgery with or without previous radiotherapy may result in difficult and dangerous complications such as osteoradionecrosis, fistula, carotid exposure and hemorrhage.

History

According to the Ebers Papyrus, the Egyptian medical compendium of the 15th century bc, chronic ulcers of the gums, which probably represented carcinoma of the alveoli were to be treated with a combination of spices, honey and oil. Skin cancers were treated similarly with potions of caustic agents which undoubtedly created a superficial coagulum and subsequent necrosis with curettage of the eschar. Hippocrates (460 bc) recommends cautery and caustic pastes for malignant tumors and used the term carcinoma because of the similarity of the shape of the large external tumors and he used the term carcinoma to describe them undoubtedly because of their apparent claw like extensions into adjacent soft tissue similar to the shape and behavior of the crab. Furthermore, he cautioned against operating on deeply invasive tumors which sentiment was institutionalized as the Doctrine of Hippocrates and followed faithfully for many years.1,2

Roman medicine was dominated by Greek concept and even Greek physicians who had had a long time communication with Egypt and the Middle East from the time of the Persian invasion of Greece in the 5th century bc and the subsequent campaigns of Alexander of Macedonia in the 4th century. Alexander’s tutor Aristotle used his conquests as a means of collecting scientific information from throughout the world. The Roman physician Celsus described the V excision of cancer of the lip in the 1st century ad. The humoral theory of disease which states that illnesses are the consequences of imbalances of the basic humors of the body was prevalent in the time of Hippocrates and persisted as the major physiologic theory of disease until a Renaissance. Galen the 2nd century ad physician to the Roman gladiators made many important anatomical discoveries because of his ability to dissect both slain gladiators and the many animals used in these games. He describes the operation of tracheostomy (probably for diphtheria or some other acute airway obstruction) in a fashion that would serve as an accurate operative note today. He, however, believed that cancer was caused by a humoral imbalance, specifically an excess of black bile. Diet and cathartics rather than surgery were recommended as the appropriate therapy and this approach persisted until the description of general anesthesia.3

The Middle Ages in Europe were characterized by slow progression of medical technique with alchemy and the humoral therapy dominating the practice of medicine and surgery often limited to amputations, cauterization and curettage. In the Arab world, however, there was a flourishing of medical knowledge partly from rediscovery of the works of Aristotle and other ancient writers and partly through the newer concept of direct observation and recording of signs and symptoms of disease processes. Physicians were highly regarded in the courts of the Arab Caliphs. Avicenna (980–1036 ad) and Albucasis (1013–1107) both performed excision of carcinoma of the lip but apparently advocated letting the defect heal by secondary intention.4

The late Middle Ages and the Renaissance marked a move away from the humoral theory of cancer and disease and an emphasis on direct observation of physiologic and anatomic events. The descriptions of the circulation by Harvey and the anatomic studies of Vesalius and others made surgery the more rational approach to head and neck cancer and other surgical problems. Oral cancer, tongue, tonsil and gum cancer were described more commonly in the 16th century, perhaps as a consequence of the importation of tobacco from the new world and the popularity of its use.5 Richard Wiseman in 1650 described the therapy of oral cancer by excision and cautery and Marchetti in 1664 and 1676 described both excision and cautery and continuous mass ligation surrounding the tumor as treatments for tongue cancer.6 This approach of mass ligation became quite popular because it mitigated some of the problems that made surgery in the oral cavity so dangerous namely hemorrhage and swelling resulting in aspiration and upper airway obstruction. To facilitate this technique instruments such as the ecraseur were developed, a noose of chain on a screw that could be gradually tightened around the tumor to cause ischemic necrosis. This with the curette, lancet and cautery remained mainstays of the surgical armamentarium against oral cancer until well after the introduction of general anesthesia.

Cancer as a disease began to acquire more attention after the Renaissance, despite the persistence of the more relevant problems of infectious disease and trauma. In 1740, the first hospital devoted primarily to the care of cancer was opened in Rheims France and was called La Lutte Contre Le Cancer (the fight against cancer). Rudolph Virchow’s work with the microscope resulted in a system of disease based on cellular pathology rather than humoral imbalance and allowed the subsequent histologic characterization of malignancy and its corollary technique of judging tumor extirpation adequate by the examination of the margins of tumor resection.7 Interestingly, Virchow’s cellular theory of malignancy stated that malignancy arose in the connective tissue and broke through to the epithelial surface rather than the more commonly seen reverse process where epithelial malignancy invades through the basement membrane into the subjacent connective tissue. Another breakthrough in understanding the natural history of cancer came in the late 18th century when the importance of lymph node metastases began to be understood and the theory of local regional spread of disease came to take center stage.8

In 1842, Crawford W. Long of Jefferson, Georgia, removed a large sebaceous cyst from the neck of one of his friends, while the friend was insensible from ether inhalation. After awakening, his friend stated that he and felt neither pain nor recalled the procedure. Unfortunately, Long did not publish this or his other experiences with ether until 1849. In 1846, at the Massachusetts General Hospital, William Thomas Green Morton administered ether to a young man with a tumor of the submandibular gland, while John Collins Warren removed the tumor surgically in the presence of numerous medical colleagues. This first public display of general anesthesia was quickly followed by numerous other successful operations and surgery changed from an infrequent approach to disease constrained by time, patient’s suffering and blood loss, to a deliberately planned technical approach to be developed to address the problems of the entire body. Surgeons in the United States and Europe began to develop operations to remove cancers throughout the body. Warren advocated a locoregional approach to tongue cancer with resection of the upper neck lymph nodes and Kocher is Austria approached the lateral tongue through the submental triangle.3

In 1873, Karl Billroth performed the first total laryngectomy for cancer of the larynx. This operation and others like it were, however, infrequently employed because of their high complication rate with up to 40% mortality in the first 8 weeks and only an 8.5% 12-month survival.9 Gluck and Sorensen in Germany persisted with laryngectomy over the next 30 years with improved survival and fewer complications.10,11 During this time, various access techniques such as lip splitting and mandibulotomy and even midline splitting of the tongue were described by Billroth, Von Langenbeck and Trotter, and the surgical concept of adequate visual and tactile exposure began to develop. Various adjuncts to surgery such as laryngoscopy with a mirror and elaborate mouth gags to provide intraoral access were also developed late in the 19th century. Hemi-laryngectomy was described in 1878 by Billroth and though rarely performed until the recent era, it did however refine laryngofissure for access to lesions of the larynx and definitive surgical removal, while preserving function.12

The concept of the locoregional approach to cancer was best stated in 1906 by George Crile of Cleveland. Crile described the radical neck dissection that is still used today in his elegant paper in the Journal of American Medical Association. His thesis stated “excision of individual lymphatic glands as one would excise a tuberculosis gland not only does not afford permanent cure but is usually followed by greater dissemination and more rapid growth”. In 132 primary excisions with associated radical neck dissection he demonstrated a 25% better 3-year survival with only an 8% mortality in a time when there were no antibiotics or blood transfusion.13 Crile used nasotracheal intubation and packing of the pharynx to avoid aspiration and ligated the external carotid and occasionally temporarily occluded the common carotid to limit blood loss.14 Butlin in England published a similar experience in 1909 with over 100 cases of partial glossectomy and upper neck dissection.15 Crile also reported that out of 4500 cases of head and neck cancer treated at the Cleveland clinic, only 1% had developed distant metastasis at the time of death confirming to the surgical public the uniquely locoregional nature of this disease. This notion however, has subsequently been mitigated with Martin demonstrating 23% distant metastasis in 284 cases.12

At about the same time, the effects of radium were described by the Curies in France. These phenomena were immediately exploited by physicians and the potential curative effects were early realized. Butlin in England15 noted regression of tongue cancer but minimal effect on cervical lymph nodes. The total doses necessary for tumor kill and control without recurrence were gradually worked out over the next 30 years by Paterson and Parker16 and have remained relatively unchanged to the present day. Early radiotherapy was delivered by interstitial implantation of radium needles and other sources known as brachytherapy which was gradually replaced by external radiation. In 1919 Coutard17 described the process of fractionation which suggested that a less toxic method of delivery of external beam radiotherapy was to divide the dose into fractions to be delivered daily until the total dose was delivered. Baclesse working on cancer of the larynx and hypopharynx put forth the notion that the hypoxic center of the tumor required more intensive dose than the entire tumor volume.18 Because of the rapid improvement in techniques of radiotherapy and the high incidence of complications in major resections of the laryngopharynx, radiotherapy became the treatment of choice for tumors of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, nasopharynx and larynx from about 1910–1940.

The advent of physiologic treatment of surgical patients beginning before the Second World War and continuing after that, with the beginnings of blood transfusion and the discovery of antibiotics made major surgeries more attractive. Poor rates of cure for oral cancers and recognition of the many complications associated with intensive radiotherapy stimulated Grant Ward and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins Hospital to extend Crile’s operative principles to involve the mandible or intervening lymphatics as the composite resection of the primary tumor and neck.19 This technique was further developed by Hayes, Martin and others at Memorial Hospital in New York City during the Second World War and received the name Commando procedure in tribute the efforts of American Commando raiders in Northern France.12

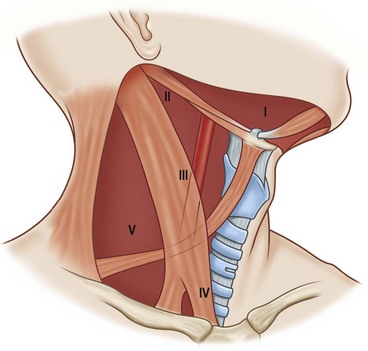

In the 1960s, Ballantyne at MD Anderson Cancer Institute and Bocca in Italy, described modifications of the radical neck dissection aimed at preserving as much function as possible by preserving the accessory nerve and the internal jugular vein as well as other structures without sacrificing effective tumor resection.20,21 These techniques ultimately were modified by Byers and others in the 1970s and 1980 to elucidate the concept of the selective neck dissection which in the N0 neck removes only those lymph node compartments likely to be affected by metastasis as predicted by the site of the primary lesion.22

The logical consequence of having two therapies for a disease process that often presents late and has a high recurrence rate is to combine the two methods in an adjuvant fashion to try to improve cure rate and decrease the radicality of surgery. This concept was further stimulated by the recognition that surgery after radiotherapy for curative intent resulted in a high rate of serious complications such as fistulae and subsequently ruptured carotid vessels.23 Fletcher at MD Anderson and others, particularly in Toronto and Europe, advocated combined surgery and radiotherapy.24 Lindberg and others citing decreased complications and increased tumoricidal affect by a given dose of radiation on microscopic as opposed to macroscopic disease advocated definitive surgery of the primary and neck followed by adjuvant radiotherapy in doses of 5000–6000 Centigray to the primary bed and neck depending on the pathologic status of the primary resection and the neck.25

In the 1950s, surgeons and other investigators recognized the tumoricidal affects of certain drugs particularly the anti-metabolite methotrexate. Multiple drugs and combinations of drugs were put through trial but the results were disappointing.26 Ultimately, however, it was noted that the use of induction chemotherapy with a combination of Cisplatin and 5FU would predict response to radiotherapy and the Veterans Affairs Laryngeal study group showed comparable disease free survival of patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy to patients treated with laryngectomy and radiotherapy. In the neoadjuvant group, laryngeal salvage was accomplished in over 60% of cases.27,28 This successful approach was repeated in the 1990s and the concept of organ preservation has been extended to advanced hypopharyngeal and oropharyngeal cancers.

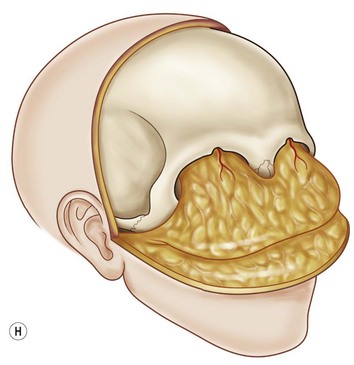

In the 1960s, the combined intracranial and extracranial approach to advanced tumors of the sinuses, nasal cavity and nasopharynx and occasionally the base of skull was described and found to be adequately safe and efficacious to encourage the growth of a subspecialty of head and neck surgery, craniofacial or skull base surgery. This approach combined with techniques used in the treatment of congenital deformities and neurosurgical techniques has resulted in a more rational and feasible approach to advanced tumors of the orbit and skull base.29–31

Basic science

Head and neck cancer has long been considered a classic example of chemical carcinogenesis, most simply a two-part process where one carcinogen initiates the process and another promotes the subsequent growth of cancer. Tobacco is the initiating carcinogen most likely the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzopyrene which are produced in tobacco smoke. These are inhaled affecting the larynx and lung lining. They enter the blood stream and are secreted in the saliva where they can bathe the oral cavity and pharynx particularly in areas where saliva pools such as the floor of the mouth, the lateral tongue, the base of the tongue, the supraglottic larynx and the pyriform sinuses. These hydrocarbons affect the genetic material in the mucosal cells which are already in an inflammatory state because of the action of the promoting agent. In the Western world, the most common promoting agent is alcohol, as demonstrated by the high incidence of disease in patients who chronically use tobacco and alcohol. In South Asia which has a very high incidence of head and neck cancer submucous fibrosis appears to be the promoting factor with the tobacco and betel nut in pan an oral chew as the initiating factor. Other associations are with iron deficiency anemia in the Plummer–Vinson syndrome in Northern Europe and Vitamin A deficiency. Several occupational exposures have been considered promoting agents particularly nickel, radium, mustard gas, and wood dust.32

There has been a long recognized association between viral infection or colonization and head and neck cancer. Epstein–Barr virus infection is almost universal in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Recently, a strong epidemiologic association has been found between patients infected with human papilloma virus (HPV) and cancer of the tonsil and base of the tongue. It is theorized that the DNA from HPV type 16, 18, and 31 are highly active and may inactivate tumor suppressor genes resulting in tumor growth. Other genetics alterations have been frequently seen in head and neck cancer. Amplification of the oncogene cyclin has been reported. Mutation in the TP53 gene increases the risk of initial carcinogenesis and early recurrence and is seen more frequently in tobacco and alcohol use than in patients infected with the HPV suggesting different genetic pathways to a common neoplastic outcome.33 Progression of head and neck cancers has been associated with amplification of the CDKN2A or p16 gene. Increased expression of the receptor for epithelial growth factor (EGFR) and certain EGFR mutations have been shown to predict poor prognosis and resistance to the tumor therapeutic cetuximab.

The model of chemical carcinogenesis suggests that the entire mucosal field of the upper aerodigestive tract is at risk for development of cancer. Clinical and histologic evidence of this field effect is commonly seen in patients with head and neck cancer. The earliest or precancerous manifestation of this is leukoplakia or a white patch, a collection of hyperkeratotic hyperplastic cells with some mild dysplasia. Erythroplakia is a more aggressive change and may in fact harbor areas of invasive or in situ malignancy. This is an erythematous plaque, in which there is architectural disorganization of the mucosal cells and dysplasia with some nuclear alterations but no invasion of the basement membrane. Carcinoma in situ has frank malignant changes of the cells but confinement above the basement membrane. Verrucous carcinoma is a more indolent malignant change and frank invasive carcinoma invades into the underlying stroma. This field effect suggests that there might be a high incidence of synchronous primary cancers in the upper aerodigestive tract (5–7%) and a high incidence of secondary primary cancers a phenomenon that is seen clinically (20–30%). Although patients may have disseminated systemic carcinoma without cervical lymphadenopathy, the most common pathway of growth is locally, metastases to the regional lymph nodes and ultimately distant metastases (Fig. 16.1).

Epidemiology

In the United States, head and neck cancer is a relatively uncommon disease making up about 3.2% of new cancers (c. 40 000/year) and 22% of cancer deaths (12 460).32 The incidence is 270 cases per million US population as opposed to 520 million for colon cancer and 620 million for lung cancer. In the United States, if all the cancers of the head and neck are included, thyroid is the most common (29%), followed by larynx (15%), oropharyngeal mucosa (12%), and tongue (10%). The pathogenesis of thyroid cancer is completely different from that of mucosal carcinomas.34 Most cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract arise from the respiratory epithelium and present as squamous cell carcinoma (80%), lip, tongue, tonsil, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and cervical esophagus. Adenocarcinoma is the second most common histology usually arising from the minor salivary glands in the area. Various types of sarcoma are less common.

Worldwide, particularly in developing countries, head and neck cancer is a bigger public health problem. It is estimated that there are 644 000 new cases and 300 000 deaths per year.32 Including the world population, the most common site of presentation is the oral cavity. The countries with the highest per capita incidence of head and neck cancer are India followed by Australia, France, Brazil, and South Africa. In India, one-quarter of new cancers occur in the head and neck. In the US, the overall incidence of this disease is decreasing because of public health efforts that have been successful in diminishing tobacco use. Worldwide, however, the incidence and mortality is increasing and the 371 000 deaths from mouth and oropharyngeal cancer recorded in 2008 are projected to increase to 595 000 in 2030 because of the 40-year lag time related to tobacco effects in those countries more recently exposed to tobacco products such as in Africa and South-east Asia.35 There has been a well established correlation between income and education and head and neck cancer, with an increased incidence in those patients suffering poverty and malnutrition.36

In the US, the male : female incidence ratio is three to one with a higher per capita incidence in blacks than whites, and an overall poorer survival in blacks. In Europe, 90% of patients affected are over 40 years of age and 50% are over 60. Worldwide, the ages are somewhat lower. In the developed world, there has been a rising incidence of disease in younger age groups, particularly related to HPV infection and probably its venereal transmission, since it is much more common in patients who have a family history of HPV infection or six or more sexual partners. This increase in head and neck cancers has paralleled a rapid rise in HPV infection in the developed world. These HPV associated tumors have a better survival rate than those related solely to tobacco and alcohol.37

As previously noted, the major risk factor is tobacco use which increases risk 5.25 times over nonsmokers in a dose-dependent relationship. Alcohol is both a co-factor and an independent risk factor with a two times greater incidence in nonsmoking consumers of alcohol. In a patient with a 40-pack/year history, who consumes five or more drinks/day, there is a 40 times increased risk of head and neck cancer.38 Cessation of tobacco use alone or tobacco and alcohol use results in decreased risk approaching that of never having smoked or taken alcohol at 20 years.39 Cessation also decreases the risk of metachronous upper aerodigestive tract tumors.

Patient presentation

Further definition of the primary tumor site can be obtained by computerized tomography (CT) if bone is involved or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if the tumor is in soft tissue alone. Chest X-ray should be obtained in all patients because of the high incidence of primary and metachronous lesions. In later stage locoregional disease, particularly if there is a suspicion of distant metastases PET-CT scan may be useful although their sensitivity is greater than their specificity and several studies have shown no increase in accuracy of diagnosis when PET-CT is used to assess the neck.40 The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in evaluating the N0 neck has not been definitively determined. Clinically suspicious palpable masses in the neck should be evaluated by aspiration cytology which has a very high sensitivity and specificity. Nutritional parameters should be monitored as well as hemoglobin levels since many head and neck patients are malnourished, anemic and relatively dehydrated. If there is dysphagia or alimentary tract obstruction enteral feeding and rehydration should be undertaken prior to therapy although parenteral feeding has been shown to decrease survival. Because depression is 10 times more common in patients with head and neck than in the general public, a careful mental status examination and appropriate therapy should be undertaken prior to initiating major surgical or radiotherapeutic treatment.

Staging

Head and neck cancers like other solid tumors, are described for clinical purposes by staging. The American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) have established a method called TNM (tumor, nodal metastasis, metastases systemic), which characterizes the lesion in an anatomic fashion at the time of its clinical presentation (Table 16.1). This system has been used relatively effectively to predict prognosis, determine treatment plans and to compare the effectiveness of various therapies. For the head and neck standard anatomic subsites have been determined, lips and oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, and thyroid gland. T-stage depends for the most part on size but also to some degree on adjacent structures affected. N-status depends on size, number and laterality of the cervical lymph nodes. M-status is self-evident.41 The combination of characteristics describes the stage of the lesion. It is critical that the stage be accurately determined and recorded on presentation since it allows accurate translation of information and determination of prognosis and choice of therapy.

There has been much study oriented to improving the accuracy of staging systems in head and neck cancer. Anatomic staging provided by the TNM system may be inaccurate because of the difficulty in examining the head and neck with its complex anatomy, leading to underestimation of tumor size and the presence of lymph nodes particularly in the obese patient with a thick neck. Moreover, TNM staging does not address the variability of tumor biology and histology. Histologic variations, tumor thickness, such as the Breslow classification for melanoma and other parameters have been suggested as adjunct to the TNM system but have not been widely accepted. Present research is based on the concept that the head and neck cancer like all other cancers is the result of an accumulation of genetic alterations that results in clonal populations that exhibit independent growth mechanisms and outgrow the normal organ. This theory suggests that the addition of molecular markers of malignancy such as the abnormal expression of EGFR, Cyclin D1, HPV DNA, p53 gene and others be combined with TNM to better predict tumor behavior and prognosis and to help in selecting targeted therapies. Future research in this direction will determine the utility of these methods.42

Therapeutic choices

The desire to preserve function and the discovery of chemotherapeutic combinations or targeted therapies that are more cytotoxic to head and neck cancers has lead to an increased interest in organ preservation with induction chemotherapy and definitive radiotherapy. The success in laryngeal preservation demonstrated in the VA study and others has encouraged extension of this principle to other sites with mixed success in an attempt to avoid surgery altogether. Pre-radiotherapy or concurrent chemotherapy regimens have been used and a 62% organ salvage rate accomplished.43 Salvage surgery (surgery for persistences and or recurrence) may be used if combined therapy is not successful. The use of chemotherapy as an adjuvant to radiotherapy in the postoperative setting has also been advocated but reports of it success are mixed.44,45 The use of new reconstructive and extirpative techniques appears to have decreased the risks of complications for surgery performed after definitive radiotherapy and chemotherapy.46

Surgical access

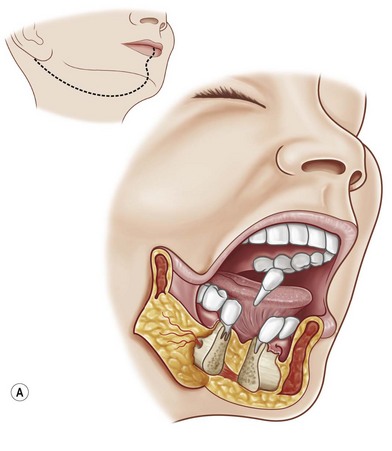

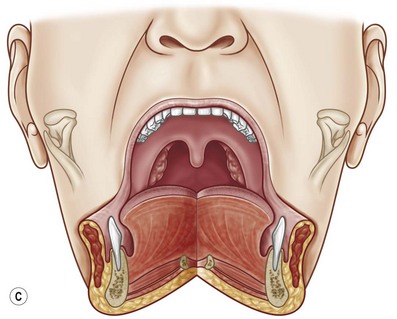

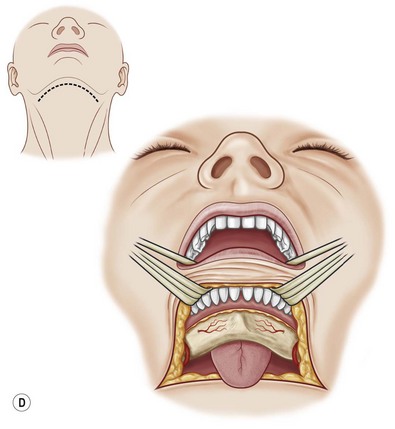

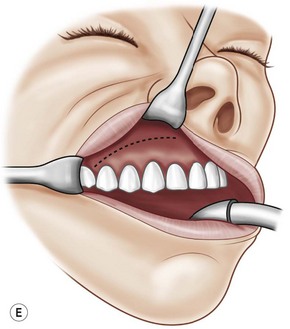

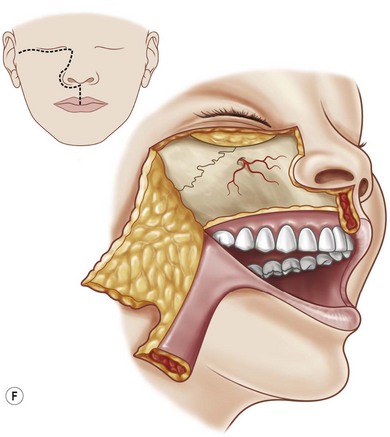

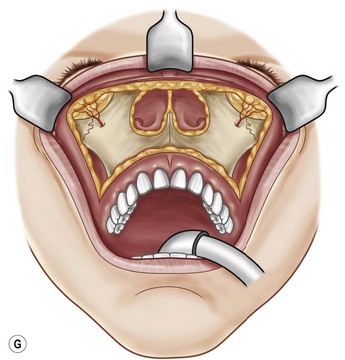

Lip splitting (labiotomy) incisions are usually planned as midline to allow the best symmetry and to avoid vascular embarrassment. Mandibulotomy should be midline or mesial to the egress of the mental nerve from the mandible to preserve sensation of the lip. If necessary, the mental nerve can be sacrificed and mandibulotomy performed on the vertical ramus above the entry of the inferior alveolar nerve to access the base of the tongue. Extension of the mandibulotomy can be along the floor of the mouth for exposure of the tonsil or retromolar trigone or midline through the tongue and palate to expose the nasopharynx, posterior pharynx or supraglottic larynx (Trotter approach). For access to the nose, paranasal sinuses and orbit, the incision in the superior alveolar sulcus (Caldwell–Luc) can expose the unilateral maxilla and be carried up to the infraorbital nerve or beyond. Extension of this approach across the midline and laterally along both sulci can be used to create a facial degloving incision to provide access to the total midface. When this incision is combined with a bilateral coronal incision it gives excellent access to the midface, orbits, skull base and sinuses. Unilateral exposure to the nose, sinuses, palate and orbit can be obtained by the Weber–Ferguson incision which extends from a midline upper lip splitting incision along the folds linking the juncture between the lip, cheek and nose, and extended above or below the eyelids or through the medial canthus depending on the structures that needs to be exposed (Fig. 16.2).