Most of the tumors described in this chapter can be diagnosed on the basis of histologic features in hematoxylin–eosin–stained sections. However, immunohistochemistry is essential at times (Table 32-2). This should be used as an adjunct to standard histologic methods and clinical data. Additional techniques such as cytogenetics and electron microscopy can also be of value in categorizing some tumors. Chromosomal aberrations frequently associated with some of the entities in this chapter are summarized in Table 32-3. The possibility that a malignant lesion represents a metastasis must always be considered.

SO-CALLED FIBROHISTIOCYTIC TUMORS

The term “fibrohistiocytic” is somewhat controversial and has been criticized in the WHO classification of soft tissue tumors (1), and some of these lesions may be better regarded as of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic differentiation. Nevertheless, there are tumors whose cells exhibit features suggesting histiocytic differentiation (e.g. foam cells, giant cells, CD68 expression), while synthesizing collagen (suggesting fibroblastic differentiation). The term “fibrohistiocytic” has therefore been retained for these skin lesions.

Benign

These are tumors with little or no potential for metastasis. Nevertheless, there are rare exceptions such as cellular dermatofibroma (discussed in the next section). Some of these lesions can persist locally and may occasionally recur or progress. Local excision is considered adequate treatment for most (e.g., common dermatofibroma), the majority tending to regress even if only partially removed. For other lesions, complete excision is recommended.

Dermatofibroma (Fibrous Histiocytoma/Sclerosing Hemangioma)

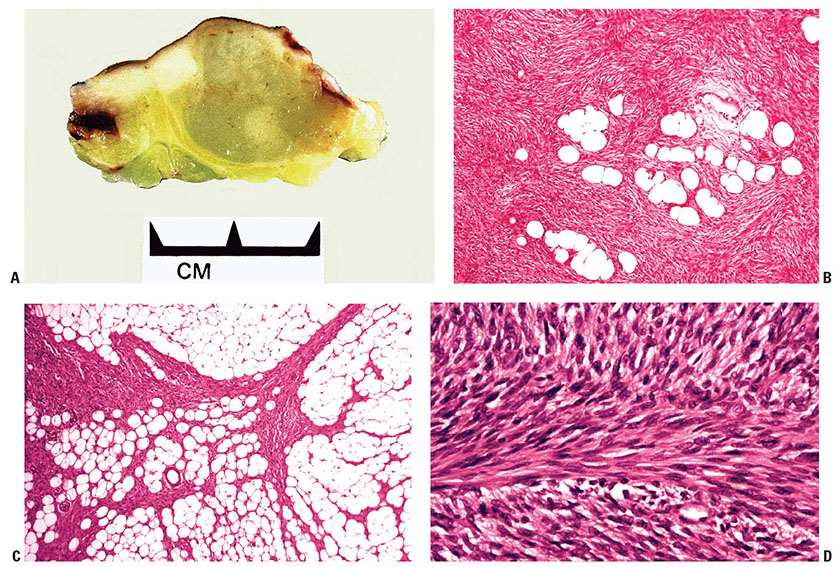

Clinical Summary. Dermatofibromas (fibrous histiocytomas) are common skin tumors predominantly occurring on the extremities or trunk of young adults. They present as small, firm, solitary nodules that are red to brown in color, often due to increased intraepidermal melanin or tumoral hemosiderin. This may suggest a melanocytic lesion clinically. Dermatofibromas are seen only rarely on the palms and soles (3) and are relatively uncommon on the face, where they are more likely to recur (4). Multiple tumors have been reported, associated with immunosuppressive therapy (5), pregnancy (6), HIV infection (7), and after antiretroviral therapy (8). Although most lesions are usually only a few millimeters in diameter, they occasionally measure 2 to 3 cm. The cut surface is white to yellow or brown, depending on the proportions of fibrous tissue, lipid, and hemosiderin present (Fig. 32-1A). Dermatofibromas usually persist, although spontaneous involution has been observed (9).

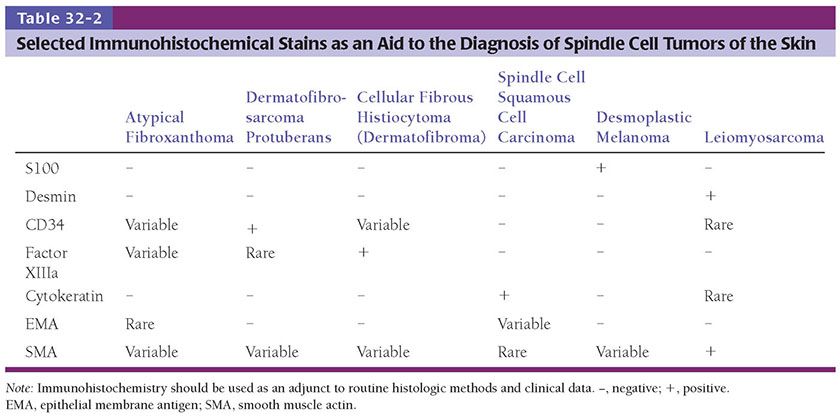

Figure 32-1 Dermatofibroma (fibrous histiocytoma). A: Gross specimen. A poorly circumscribed dermal lesion is present with overlying increased epidermal pigmentation and acanthosis. The tumor has a yellow cut surface with focal hemorrhage present centrally. B: The epidermis is hyperplastic and separated by a narrow clear zone from a moderately cellular spindle cell tumor extending into the deep dermis. C: The tumor is composed of variably-sized spindle cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm in a collagenous stroma. D: This dermatofibroma shows prominent hyalinization and pigmentation. E: Hemosiderin and multinucleated giant cells dominate in this zone of another dermatofibroma.

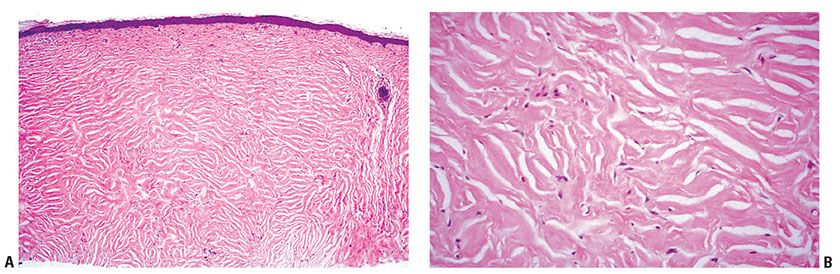

Histopathology. The epidermis is usually hyperplastic, with hyperpigmentation of the basal layer and elongation of the rete ridges, separated by a clear (Grenz) zone from the tumor in the dermis (Fig. 32-1B). This is composed of fibroblast-like spindle cells, histiocytes, and blood vessels in varying proportions (Fig. 32-1C–E). Foamy histiocytes and multinucleate giant cells containing lipid or hemosiderin are frequently present, sometimes in large numbers, forming xanthomatous aggregates. Prominent lipid accumulation is seen in the lipidized (“ankle type”) dermatofibroma. Capillaries may be plentiful in the stroma, giving the lesion an angiomatous appearance. When there is also associated sclerosis, such lesions have been referred to as “sclerosing hemangioma.” Some dermatofibromas may be poorly cellular and subtle, with spindle cells extending between collagen bundles associated with apparent “rounding up” of collagen fibers. More cellular forms often exhibit a storiform pattern of interwoven, fascicled spindle cells. Tumors are typically poorly demarcated.

Significant hyperplasia of the overlying epidermis occurs in more than 80% of dermatofibromas (10) and assists in making the diagnosis and distinguishing the atypical variant from atypical fibroxanthoma (11). Hyperplasia usually consists of regular rete ridge elongation, often with hyperpigmentation of basal keratinocytes. In some cases, the changes resemble a seborrheic keratosis, and, occasionally, downgrowths show hair matrical differentiation (12). In up to 5% of dermatofibromas the downgrowths show areas that closely resemble superficial basal cell carcinoma (13). In rare instances, genuine invasive basal cell carcinoma development has been documented (14,15).

Principles of Management. Local excision is considered adequate treatment, with most lesions tending to regress even if only partially removed. Complete excision of facial lesions has been recommended due to their increased risk of recurrence (4).

Dermatofibroma Variants

Cellular Fibrous Histiocytoma (Dermatofibroma)

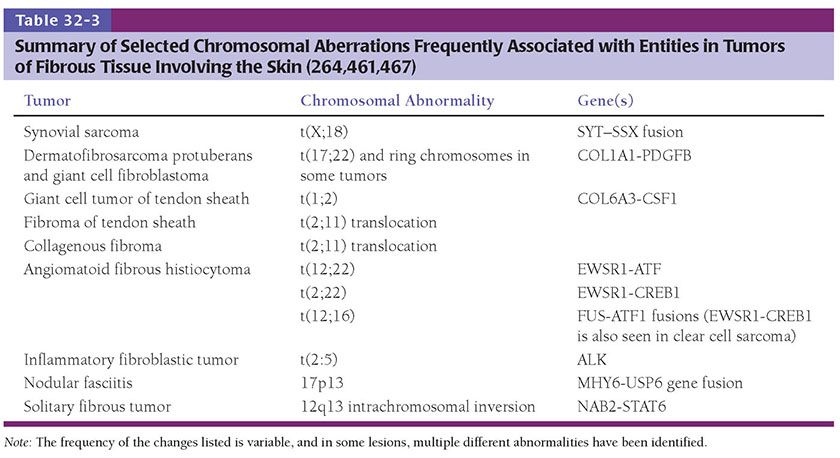

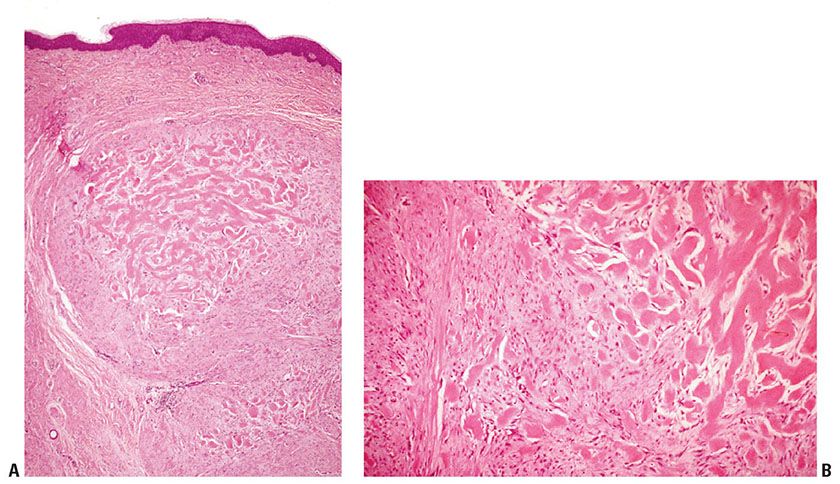

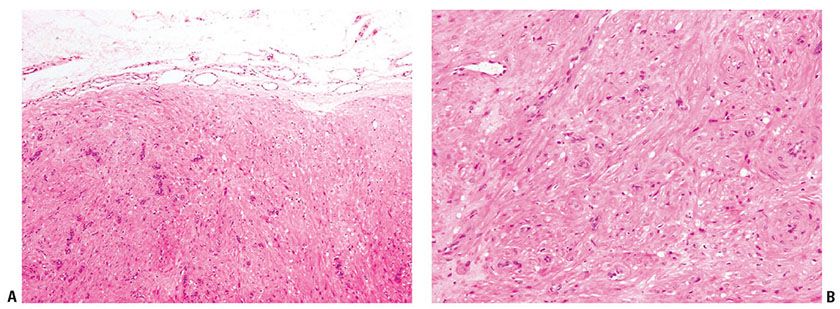

Clinical Summary and Histopathology. This is a rare, densely cellular variant with a fascicular-to-storiform growth pattern and frequent extension into subcutis (Fig. 32-2A, B). The tumors occur on the head and neck or trunk and may mimic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) histologically. Identification of areas of more typical dermatofibroma assists in making this differentiation (16,17). Paradoxically, cellular atypia is often more pronounced in these tumors than in DFSP, and factor XIIIa staining is often negative (16). Areas of CD34 positivity may be present, but only focally at the edge of the tumor. Foci of smooth muscle actin (SMA) positivity are frequent, but staining with desmin is rare (18).

Figure 32-2 Cellular dermatofibroma (fibrous histiocytoma). A: The tumor consists of spindle cells arranged in densely cellular fascicles with storiform areas. B: At the border of the lesion the spindle cells surround individual collagen bundles.

Principles of Management. Complete surgical excision is advised because of an increased risk of recurrence, with rare metastases to regional nodes and the lung reported (16–20).

Aneurysmal Fibrous Histiocytoma

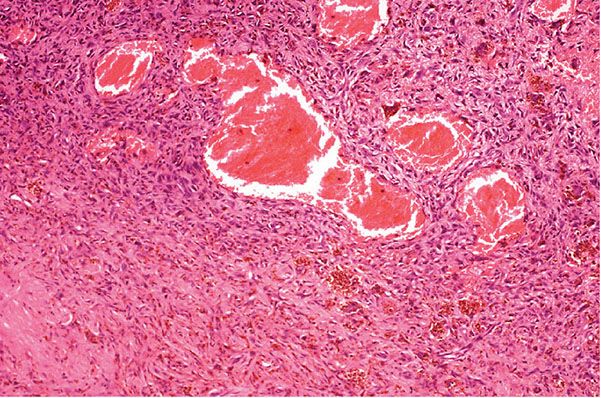

Histopathology. In these tumors, collections of capillaries, foci of hemorrhage, siderophages, and foamy macrophages surround cleft-like and cavernous blood-filled spaces in the center of the tumor. They are most frequently encountered on the limbs and may be several centimeters in size. The pseudovascular areas may dominate, simulating a vascular neoplasm, but intervening areas show more typical features of dermatofibroma (21,22) (Fig. 32-3). There is limited or no involvement of subcutis. To avoid confusion with angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma (a tumor of intermediate malignancy; see later discussion), it has been suggested that these tumors should be referred to as “dermatofibroma with aneurysmal change” (23). One case has shown a t(12;19) translocation (24).

Figure 32-3 Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). Dilated blood-filled spaces are prominent in this variant, with associated hemorrhage. Bland spindle cells and siderophages are seen in the surrounding tissue.

Principles of Management. Since a minority of lesions recur, complete excision is appropriate (18).

Atypical (Pseudosarcomatous) Fibrous Histiocytoma

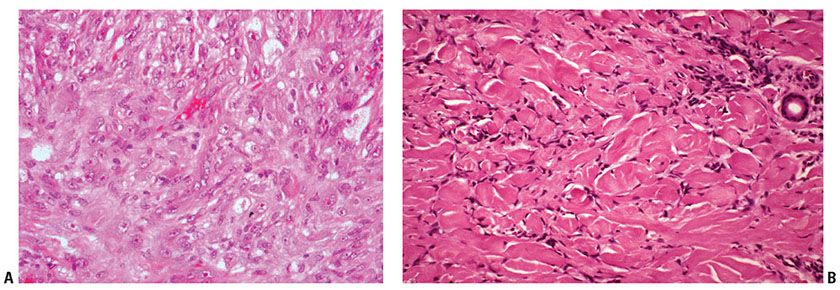

Histopathology. Atypical cells are occasionally present in dermatofibroma, which may lead to misdiagnosis as atypical fibroxanthoma (11,25), and there is some overlap with cellular fibrous histiocytoma histologically. These tumors are usually small but occasionally reach 2.5 cm or greater in diameter (26). The atypical cells show enlarged, pleomorphic nuclei, sometimes referred to as “monster cells” (dermatofibroma with monster cells) (26,27). Mitoses of normal morphology may be evident in large numbers, and atypical mitotic figures have also been reported. Multinucleated giant cells with bizarre, large, hyperchromatic nuclei with little cytoplasm or irregular, vesicular nuclei with abundant foamy cytoplasm may also occur (Fig. 32-4A, B) (11). Extension into superficial subcutis and focal necrosis may be seen. The presence of more typical appearing dermatofibroma in the background is very helpful to enable the correct diagnosis in these lesions (28). Variable staining for SMA and CD34 are reported, with no staining for factor XIIIa.

Figure 32-4 Atypical fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). A: This tumor shows histiocyte-like cells with enlarged and pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. B: At the border of this tumor the cells are arranged around individual collagen bundles in the pattern typical of the more usual form of dermatofibroma.

Principles of Management. Complete excision is required because of a significant risk of recurrence and very occasional metastases (28).

Epithelioid Fibrous Histiocytoma

Histopathology. This distinctive variant, originally described as epithelioid cell histiocytoma (29), is composed of cells showing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with occasional multinucleated forms. Areas of spindle cell forms may also be present with a complement of foamy macrophages. Tumors form an exophytic nodule with an epidermal collarette resembling pyogenic granuloma or intradermal Spitz nevus (Fig. 32-5) (30,31). The lesions are often well circumscribed. Immunohistochemistry may be required to differentiate the lesion from a melanocytic proliferation, for example. The tumor shows the expected staining pattern of a dermatofibroma.

Figure 32-5 Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). The lesion shows sheets of epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Differentiation from a melanocytic lesion such as a Spitz nevus may require immunohistochemistry in some cases.

Principles of Management. Local excision is considered adequate treatment, as for the more usual forms of fibrous histiocytoma.

Deep Fibrous Histiocytoma

Clinical Summary and Histopathology. This is a rare form that develops entirely within subcutaneous tissue, deep soft tissue, or parenchymal organs (32). Unlike typical dermatofibroma, deep fibrous histiocytoma tends to be well circumscribed, with a pseudocapsule and foci of hemorrhage consisting of monomorphic spindle cells resembling the cellular variant (33). Only one of seven cases recently studied cytogenetically showed a t(16;17) translocation, suggesting that this is a sporadic or rare event in deep fibrous histiocytoma (34). In the largest series to date of 69 cases, 20% recurred, with metastasis in 2 cases (35). Both of the metastatic lesions were large tumors with a fatal outcome.

Principles of Management. Complete excision is indicated because of the risk of recurrence or, rarely, metastasis.

Other less common variants include clear cell (36), granular cell (37), lipidized (38), myxoid (39), myofibroblastic (40), osteoclastic (41), keloidal (42), atrophic (43), and palisading forms (44). Rarely, bone formation is seen with osteoclast-like giant cells (45).

Neoplasm Versus Reactive Process

It remains unclear whether dermatofibromas are true neoplasms or reactive processes following minor trauma, such as an insect bite. This has given rise to the term “nodular subepidermal fibrosis” (41), with some authorities regarding the lesions as fibrosing inflammatory processes, even in the presence of “monster cells” (26,47). The demonstration of clonality in some cases of dermatofibroma (48,49,34) and reports of metastasizing dermatofibroma (see later), however, suggest a neoplastic nature in at least some forms. Analysis of X chromosome inactivation in 31 dermatofibromas showed a variable pattern, suggesting that the lesions are heterogeneous, with some being reactive and others possibly neoplastic in nature (50–53).

Pathogenesis. Enzyme histochemical, electron microscopic, and immunohistochemical studies have suggested histiocytic, myofibroblastic, and fibroblastic differentiation, possibly indicating a cell of primitive mesenchymal origin (54). The term dermal dendrocytoma has been proposed on the basis of immunohistochemical studies using antibodies to factor XIIIa (a marker of normal dermal dendrocytes) and the histiocytic marker MAC 387 (55,56). Most cells in these tumors were found to react with factor XIIIa, whereas only a few were MAC 387 positive. Other investigators, however, believe that the factor XIIIa–positive cells seen in fibrous histiocytomas represent included reactive stromal cells rather than the true tumor cells (54,57), which often express vimentin and SMA (57). Electron microscopic studies have variously described the cells of fibrous histiocytomas as fibroblasts, histiocytes, and myofibroblasts (58–60).

Enzyme Histochemistry. The results of enzyme studies on dermatofibromas have shown variable reactions. Positive staining for lysozyme and α1-antitrypsin have been interpreted as indicating histiocytic differentiation (61,62), whereas negative results for these enzymes have led to speculation that the fibroblastic and histiocyte-like cells in these tumors arise from primitive mesenchymal cells (63). The presence of HLA-DR antigens in the majority of cells in dermatofibromas has also been regarded as evidence in favor of a histiocytic origin (64).

Differential Diagnosis. The cellular variant of dermatofibroma must be distinguished from DFSP. Points of distinction are that dermatofibromas show overlying epidermal hyperplasia, a heterogeneous population of tumor cells, often with more pleomorphism, and extension of tumor cells at the edge of the lesion around individual hyalinized collagen bundles (65). Cellular fibrous histiocytoma also extends into subcutis along the interlobular septa or in a bulging, expansile pattern rather than in the characteristic infiltrating honeycomb-like pattern of DFSP (17). DFSP is usually a larger lesion at the time of diagnosis, often consisting of multiple nodules. Cellular fibrous histiocytoma may also be confused with leiomyosarcoma, but this has plumper spindle cells, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei with rounded ends, and shows positive staining for desmin and α-SMA (54). It should be noted that some dermatofibromas may express CD34, particularly at the periphery of the lesion, and some DFSP may express factor XIIIa (66). This has led to the suggestion of a biological spectrum between fibrous histiocytoma and DFSP, with coexistence of two different cell populations in indeterminate lesions (67). Tenascin (an extracellular matrix glycoprotein) expression has been demonstrated immunohistochemically at the dermoepidermal junction overlying fibrous histiocytomas but not DFSP (68,69).

Fibrous histiocytoma with aneurysmal change (aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) may be confused with neoplasms of vascular origin. Distinction can be made by demonstrating that factor VIII, CD31, and CD34 do not outline the apparent vascular spaces in fibrous histiocytoma, in contrast to true vascular lesions. Kaposi sarcoma shows slitlike spaces containing erythrocytes and a monomorphic CD34-positive spindle cell population (54). Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma is distinguished by its presentation in a younger age group (sometimes with systemic symptoms), subcutaneous location and the presence of eosinophilic histiocytoid cells, a prominent lymphocytic infiltrate, and a thick pseudocapsule (70,71).

Epithelioid dermatofibroma (epithelioid cell histiocytoma) can resemble Spitz nevus and pyogenic granuloma clinically and histologically (31). The lesion differs from pyogenic granuloma by the presence of epithelioid cells between blood vessels, which are not arranged in lobules, with a less prominent inflammatory component and lack of protuberant endothelial cells. Intradermal Spitz nevus has a nested pattern superficially, spindle as well as epithelioid cells, intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions, maturation with depth, and, frequently, Kamino bodies in the epidermis. Immunostaining of Spitz nevi reveals positivity for S100 and other melanocyte markers and negative staining for factor XIIIa.

Atypical fibroxanthoma differs from atypical dermatofibroma by its typical location on sun-exposed skin of the head and neck of elderly patients, frequent ulceration, severe cellular pleomorphism, numerous mitoses, including atypical forms, and the lack of a background of more usual dermatofibroma.

Metastasizing Fibrous Histiocytoma

Clinical Summary and Histopathology. Sporadic cases of metastasizing fibrous histiocytomas have been reported in the literature over the years (16,17,19,20), and in 2013, two significant series of cases were reported (72,73). In these two reports, a total of 22 cases of metastatic fibrous histiocytoma were described, which lead to the death of 8 of the patients. Factors associated with metastatic behavior tended to be large size, necrosis, prominent mitotic activity, and, in some cases, invasion of subcutis. Most of the original fibrous histiocytomas showed features of cellular, aneurysmal, or atypical variants. However, in some lesions it is difficult to predict aggressive behavior from histologic features alone (20,72). Chromosomal aberrations identified by array-CGH (comparative genomic hybridization) may be of some value in identifying high-risk tumors (73).

Principles of Management. Close follow-up has been advised for tumors that show repeated or early recurrence (72). For metastatic disease, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy have all been used, but an optimum regime remains to be clarified (72).

Plaque-like CD34-Positive Dermal Fibroma (Medallion-like Dermal Dendrocyte Hamartoma)

Clinical Summary. This is a recently-described and rare lesion that is often congenital and tends to occur on the neck, trunk, or extremities as an indurated plaque (75–77).

Histopathology. The epidermis is typically atrophic with an upper dermal proliferation of bland spindle-shaped cells that may show limited extension into subcutis (75–77). There may be an associated myxoid stroma with fine blood vessels. Mitotic activity is not a feature.

Pathogenesis. These lesions have been considered to be either hamartomatous or reactive in nature and not related to dermal dendrocytes (76). CD34 is strongly expressed and there may be some factor XIIIa positivity, but this varies, which is considered as evidence against a dermal dendrocytic origin.

Differential Diagnosis. S100 is negative, which aids in distinction from neurofibroma, and actin is not expressed, unlike in dermatomyofibroma. One of the principal differential diagnoses is congenital atrophic DFSP. The absence of a t(17;22) translocation aids in this distinction (76).

Principles of Management. Local excision is considered adequate treatment.

Giant Cell Tumor of Tendon Sheath

Clinical Summary. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath occurs most commonly on the tendon sheath of young and middle-aged adults on the dorsum of the fingers, hands, and wrists. They can also be found on the feet and around the ankle and knee joints. Tumors are firm in consistency, with a yellowish-to-tan cut surface, and are from 1 to 3 cm in diameter. There is no tendency toward spontaneous involution. The tumor may erode the adjacent bone and, on rare occasions, may even extend into the overlying skin (78,79). The lesions are benign, although they may recur in up to 30% of cases (80). Recurrences are cured by local reexcision (81). Although it has been suggested that this tumor is an inflammatory proliferation (82), it now appears more likely that the lesions are neoplastic with evidence of monoclonal abnormalities in some cases, particularly involving chromosome 1 (80).

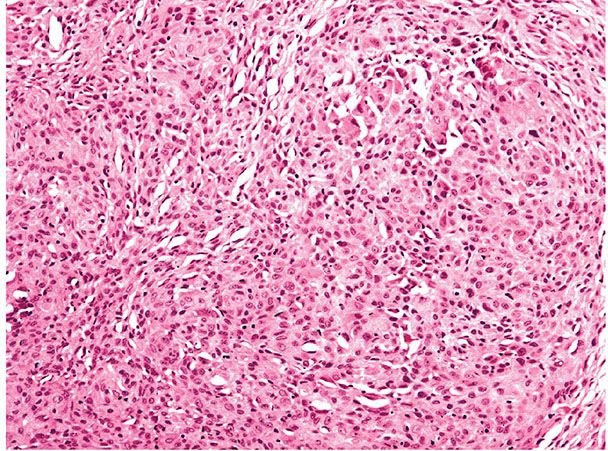

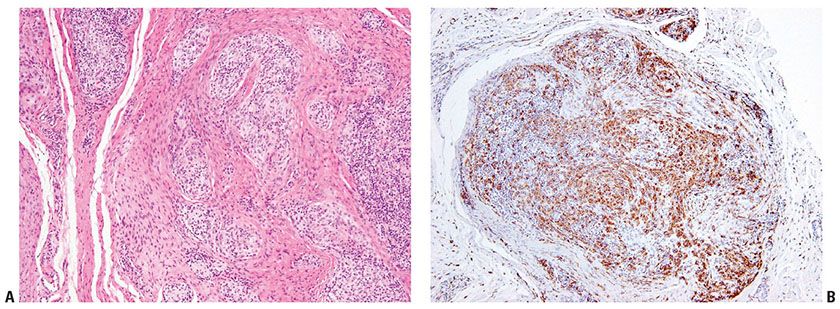

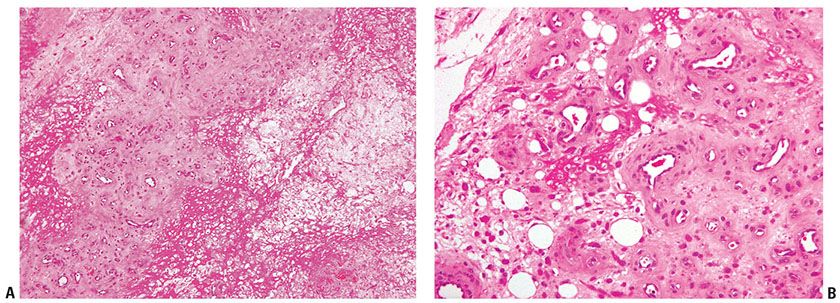

Histopathology. The tumor consists of lobules of varied cellularity surrounded by a fibrous pseudocapsule (Fig. 32-6A). In cellular areas, most cells are macrophage-like mononuclear cells with folded, kidney-shaped or grooved, oval nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. There are variable numbers of foamy macrophages, which may be associated with cholesterol clefts and siderophages. Less cellular areas consist of spindle cells within a fibrous or hyalinized stroma (78,83). The characteristic osteoclast-like giant cells (84) are scattered through both the cellular and fibrous areas. Their cytoplasm is deeply eosinophilic with often large numbers of haphazardly distributed nuclei (Fig. 32-6B). Although mitotic figures are seen in a large proportion of cases and may be frequent (85), they are not atypical. There is no evidence that mitotic activity is related to metastasis, which is an extremely rare event, but it may be associated with an increased risk of recurrence (86).

Figure 32-6 Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. A: The tumor is composed of sharply circumscribed, densely cellular lobules surrounded by fibrous tissue. B: Giant cells with multiple nuclei, resembling osteoclasts, are scattered among plump epithelioid and spindle cells.

Pathogenesis. Ultrastructural (84,87), enzyme (83), and immunohistochemical studies (83,88–90) have indicated variously that the cells may be related to synovial cells, monocytes, and osteoclasts. It should be noted that occasional dendritic cells may be desmin positive, but these do not demonstrate other skeletal muscle markers such as myogenin (80).

Principles of Management. Local excision is indicated, with recurrence occurring in a proportion of cases that are incompletely excised.

Intermediate Biological Potential (Locally Aggressive)

Lesions of intermediate biological potential may be locally aggressive, with continued, destructive growth. These lesions only rarely metastasize. Complete excision, with careful consideration of optimal margin width, is recommended.

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Clinical Summary. DFSP is a slowly growing dermal spindle cell neoplasm of intermediate malignancy. It typically forms an indurated plaque on which multiple congested, firm nodules subsequently arise, sometimes with ulceration (Fig. 32-7A). The trunk and proximal limbs of young adults are most commonly affected, with occasional involvement of the head and neck or other sites (91,92). Presentation as an atrophic lesion is occasionally a feature. A number of cases have been reported in childhood and, rarely, as congenital lesions (92–95). Local recurrence is common, and transformation to fibrosarcoma can occur, although metastasis is rare (96,97).

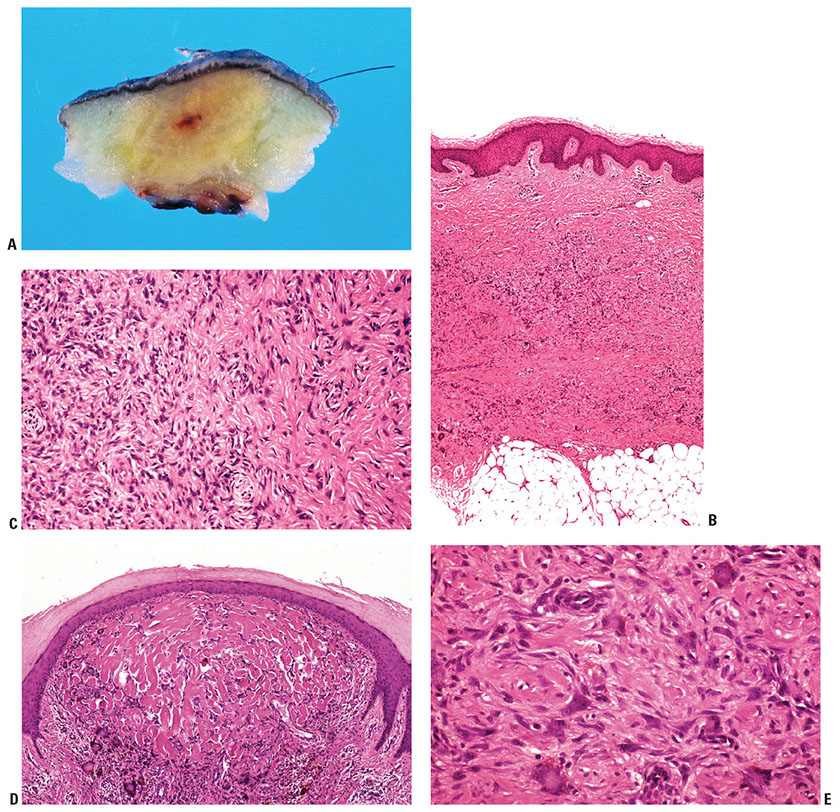

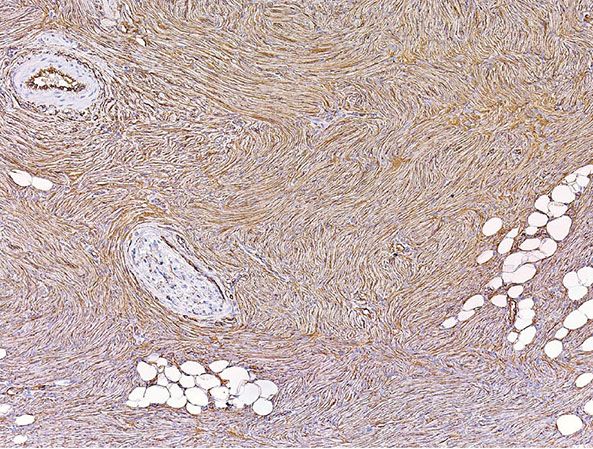

Figure 32-7 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A: Gross specimen of a myxoid variant of DFSP. The lesion is better circumscribed than the more typical form of DFSP and forms a central nodule extending into subcutis, with lateral extension in the dermis showing a component of firmer white tissue. B: Densely packed spindle cells are present, arranged in a storiform pattern extending around fat cells. C: Strands of bland spindle cells infiltrate subcutis, producing a honeycomb-like pattern. D: This DFSP exhibits an area with a prominent fibrosarcoma-like pattern. This feature is now thought to be of adverse prognostic significance (see text).

Histopathology. DFSP is composed of fascicles of densely packed, monomorphous spindle cells arranged in a storiform (mat-like) pattern. Lesions are poorly circumscribed, with diffuse infiltration of dermis and subcutis yielding a honeycomb pattern (Fig. 32-7B–D) (17). Infiltration into the underlying fascia and muscle occurs as a late event (97). Cytologically, the cells have a deceptively bland appearance, which can result in difficulty in defining the margin of the lesion. Mitotic activity is generally limited and typically less than 5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields are seen. Myxoid areas may occur, especially in recurrent tumors. Sometimes there is a vascular component of fine anastomosing blood vessels with a “chicken-wire” appearance resembling myxoid liposarcoma (Fig. 32-8) (98).

Figure 32-8 Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). This DFSP shows a myxoid appearance as it extends into subcutis. Myxoid change is more common in recurrent tumors.

Pigmented melanosome-containing cells can be identified in the tumors on rare occasions—the Bednar tumor (pigmented DFSP, storiform neurofibroma) (99–101). A number of congenital presentations of this tumor have been recorded (102).

Fibrosarcomatous areas are seen in a small proportion of DFSP, characterized by a fascicular or herringbone growth pattern (103–105). The significance of this change has been controversial, but more recent studies suggest that it carries an increased risk of metastasis and is associated with p53 mutation and increased proliferative activity (106). Giant cells are rarely seen in otherwise typical DFSP but are characteristically prominent in the juvenile variant of DFSP, giant cell fibroblastoma (see next section) (107–112).

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic studies suggest that the tumor cells are fibroblasts because they show active synthesis of collagen in a well-developed endoplasmic reticulum (113,114). In some tumors the presence of interrupted basement membrane–like material along the cell membrane suggested that the cells are modified fibroblasts with features of perineural and endoneural cells (115). Epithelial membrane antigen expression in a few cases and consistent CD34 positivity raised the possibility of a perineural origin (116). Although DFSP is commonly regarded as a fibrohistiocytic tumor, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evidence indicates that a fibroblastic origin is most likely (98,117–119). In rare instances, particularly in fibrosarcomatous forms of DFSP, bundles of eosinophilic SMA-positive spindle cells are evident in keeping with localized myofibroblastic differentiation. CD117 expression is typically absent in both DFSP and dermatofibroma (120).

Cytogenetic studies have revealed a t(17;22) translocation in more than 90% of cases of DFSP, leading to formation of a ring chromosome in some tumors (121). The translocation involves the COL1A1 gene on chromosome 17 and the platelet-derived growth factor B gene on chromosome 22. Although management of this disease continues to be primarily surgical, high rates of clinical response have been achieved through the use of imatinib to inhibit platelet-derived growth factor receptors in patients with unresectable or metastatic DFSP (122,123).

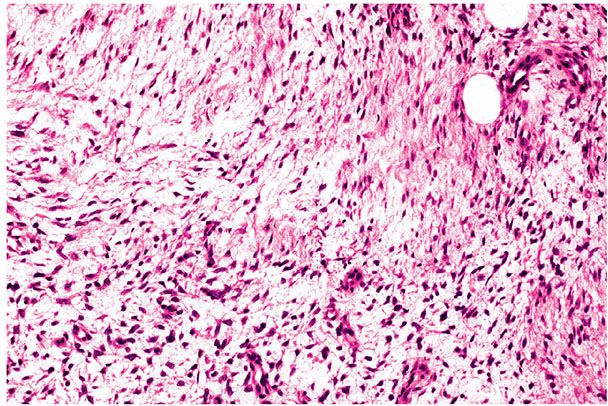

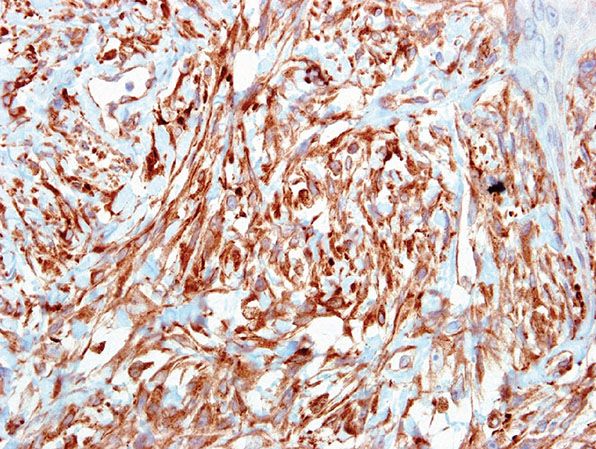

Differential Diagnosis. DFSP is generally characterized by more uniform spindle cells and a more prominent storiform pattern than that seen in dermatofibroma. Small biopsies may make assessment of architecture impossible; so caution is required in these cases. In contrast to cellular dermatofibroma, the epidermis overlying DFSP is usually attenuated or ulcerated rather than hyperplastic, and a clear (Grenz) zone between the epidermis and tumor may be absent. DFSP has a more infiltrative pattern of growth, in contrast to the well-demarcated bulging deep margin of cellular dermatofibroma, although this tumor may also extend into subcutis, predominantly along septa (17,65). CD34 staining is usually diffusely positive in DFSP and negative in most forms of dermatofibroma (124–126) (Fig. 32-9), but there is some overlap in CD34 expression (67). Some dermatofibromas exhibit a fairly characteristic pattern of peripheral “leading edge” CD34 staining, but with a conspicuous absence of staining centrally. Demonstration of tenascin at the dermoepidermal junction overlying dermatofibroma but not DFSP may help in the differential diagnosis (68,69). It has also been shown that dermatofibromas strongly express CD44 with only faint stromal hyaluronate, whereas DFSP shows reduced or absent CD44 and strong stromal hyaluronate deposition (127). Apolipoprotein D has been identified immunohistochemically in the majority of cases of DFSP but not in dermatofibromas (128). Neurofibroma expresses S100 protein, which is absent in DFSP, and shows other features of neural differentiation, without the dense, uniform cellularity of DFSP. Immunohistochemical staining for D2-40 has been reported as positive in dermatofibroma and negative in DFSP (129).

Figure 32-9 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Immunohistochemistry shows strong, uniform positivity for CD34 in the lesion. (Courtesy of Dr. E.-C. Jung, University of California, San Francisco, California.)

Principles of Management. A wide local excision with a 2-cm margin has been recommended because of the high risk of recurrence (123). The use of Mohs surgery is also a consideration, although differentiation of scar fibroblasts in reexcisions from residual tumor may be very difficult and require immunohistochemistry for CD34 on paraffin blocks (slow Mohs). Imatinib mesylate has been shown to be of some benefit in locally advanced or metastatic DFSP, as described earlier, despite the absence of stainable CD117 in DFSP (122,123,120). Tumors may be radiosensitive, but the role of radiotherapy remains to be fully established (123).

Giant Cell Fibroblastoma

Clinical Summary. Giant cell fibroblastoma represents a juvenile variant of DFSP and was first formally reported in 1989 (107). It is a rare tumor occurring mostly in children, with more than 75% of patients younger than 20 years (130). Lesions are solitary and most often sited on the trunk or thigh. Local recurrence after incomplete excision is common (131), but no metastases have been reported (132). Fibrosarcomatous change is very rare (130).

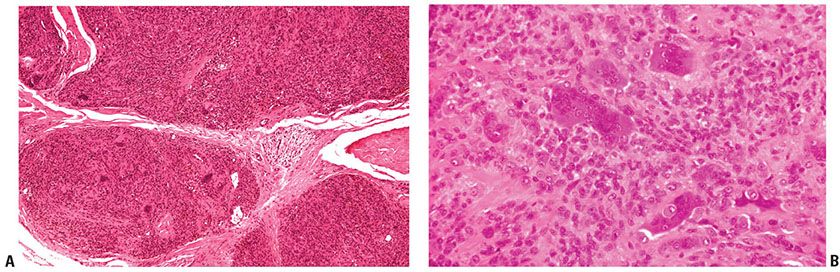

Histopathology. The proliferation is sited in the dermis and subcutis, usually with areas showing the honeycomb pattern typical of DFSP (Fig. 32-10A). In contrast, multinucleated giant cells line small clefts in the tissue (Fig. 32-10B), and foci of hemorrhage and perivascular lymphocytes may be seen (130). Zones of myxoid-to-hyalinized stroma are also present and often prominent. Electron microscopy suggests that the giant cells are not in fact multinucleated, but that the appearance represents multiple lobations of a single nucleus (107).

Figure 32-10 Giant cell fibroblastoma. A: The growth pattern resembles that of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with infiltration of subcutaneous fat by uniform spindle cells, with the additional feature of numerous giant cells. (Courtesy of Dr. I. Strungs, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, Australia, and Dr. P. W. Allen, Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, SA, Australia.) B: Numerous multinucleated giant cells are present on high power, some with pleomorphic, multilobated nuclei.

Pathogenesis. Ultrastructurally, the cells resemble fibroblasts. Immunohistochemistry shows CD34 positivity (including in the giant cells) with no staining for S100, SMA, or desmin (130,133).

The concept that giant cell fibroblastoma is a variant of DFSP is supported by the coexistence of areas of both tumors in a single lesion in some instances, the same immunogenetic and cytogenetic profile, and the recurrence of DFSP as giant cell fibroblastoma and vice versa (107–112). As in DFSP, the translocation t(17;22), sometimes forming an extra ring chromosome, has been repeatedly identified (121,134), and responsiveness to imatinib in inoperable cases might therefore be anticipated (122).

The differential diagnosis includes fibrous hamartoma of infancy (see later). Points of distinction are the patient’s age, the presence of three “zones” in fibrous hamartoma, and its lack of multinucleated cells.

Principles of Management. Wide surgical excision is indicated, with recurrences frequent if excision is incomplete (131) Recurrences may have the appearance of a DFSP.

Intermediate Biological Potential (Rarely Metastasizing)

These lesions commonly recur locally, but metastases to lymph nodes or viscera are only rarely seen.

Plexiform Fibrohistiocytic Tumor

Clinical Summary. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor is a rare multinodular neoplasm of the dermis and subcutis composed of histiocyte-like cells, fibroblasts, and multinucleate giant cells in a plexiform pattern (135). This distinctive lesion occurs as a slowly growing mass, usually involving the arm of the young, especially females. Infants are occasionally affected (136). The lesion is considered to be of intermediate biological potential, with local recurrence common but with only rare metastases to lymph nodes or viscera (137). No features predictive of recurrence or metastasis have been delineated.

Histopathology. A biphasic pattern is seen, with nodules of histiocytes surrounded by fascicles of spindle cells intersecting the stroma in a plexiform pattern. Osteoclast-like giant cells are identifiable in the majority of cases, but not all (Fig. 32-11A) (138–140). The proportion of different cellular elements varies from case to case. Mitotic activity with mild nuclear atypia and pleomorphism may be present.

Figure 32-11 Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor. A: Pale, nodular groups of histiocyte-like cells are present between collagenous bands in the dermis and subcutis. B: Immunohistochemistry demonstrates that many of the pale cells are CD68 positive.

Pathogenesis. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical studies have indicated histiocytic and myofibroblastic differentiation (137,141) in the different cellular components (Fig. 32-11B). No consistent genetic changes have been identified (142).

Differential Diagnosis. Cellular fibrous histiocytoma and dermatomyofibroma do not have the distinctive nodules of histiocytic-like cells of plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor and tend to show a cohesive growth pattern. Fibromatoses and nodular fasciitis are usually more deeply situated and lack the characteristic plexiform architecture. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy has no histiocytic nodules or giant cells (131). Lesions can be mistaken for a granulomatous process. Distinction from neurothekeoma may be problematic, especially in tumors dominated by histiocytoid cells, and some have suggested that these lesions may be related (143). Both tumors tend to express CD10 and NKIC3 (144). A lack of identifiable MiTF and S100 staining in plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors helps in this distinction (143–145). Most plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors are CD68 positive, and actin is sometimes identifiable, in addition, with an absence of desmin staining (143–145).

Principles of Management. Surgical excision is indicated, and the possibility of local recurrence, or, in exceptional cases, metastasis, should be considered, with institution of appropriate follow-up clinically.

Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Clinical Summary. Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is characterized by a malignant histologic appearance but a generally benign course with only occasional recurrences and exceptionally rare metastases (146,154,155). Lesions are typically associated with actinic damage and tend to present on the head, neck, and in particular the ear of elderly patients (154). AFX usually forms a solitary nodule up to 2 cm in diameter, often with a short history of rapid growth.

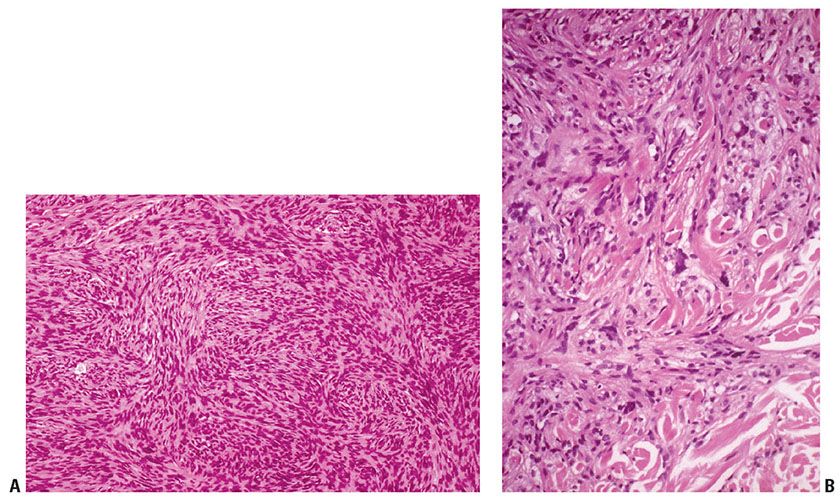

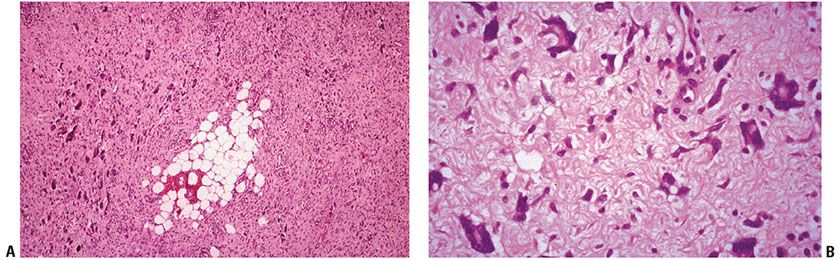

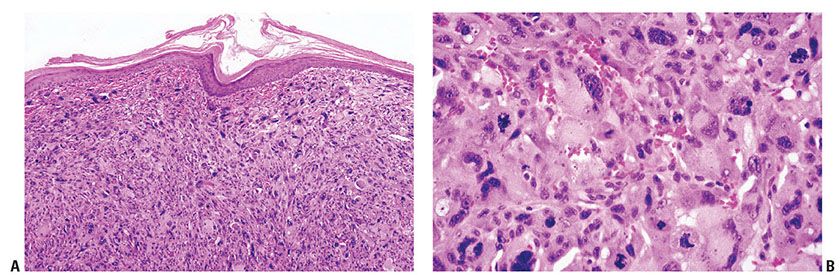

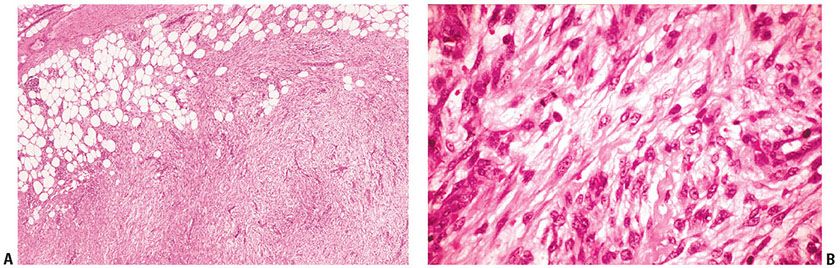

Histopathology. The lesion forms a dermal tumor with limited or no involvement of subcutis. AFXs are usually highly cellular, with marked and often striking pleomorphism and atypia of the constituent cells. Mitoses are readily identified with some atypical forms (Fig. 32-12A, B) (151,154,155). Most tumors are predominately composed of spindle cells, with areas of more epithelioid and histiocyte-like appearing forms also present. The cells may be arranged in disordered fascicles, surrounding but not destroying adnexal structures. An epidermal collarette is often seen, with ulceration frequent. Scattered inflammatory cells are present, sometimes with focal hemorrhage.

Figure 32-12 Atypical fibroxanthoma. A: The tumor is composed of a cellular mass of malignant cells that are unconnected to the epidermis. A lack of keratinization and pigmentation are clues to the diagnosis in these pleomorphic tumors, but immunohistochemistry is recommended in all cases for definitive diagnosis. B: Highly pleomorphic spindle cells are present with some multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms.

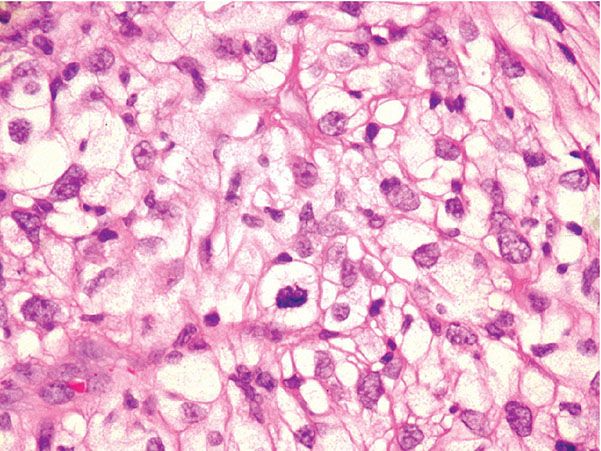

The spindle cell variant of AFX consists exclusively of spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli arranged in fascicles. Some examples of this subtype have a somewhat more regular and bland cytologic appearance, and a plaquelike pattern of growth may be evident (Fig. 32-13A, B) (146,151). Clear cell AFX is a rare variant composed of sheets of large cells with foamy cytoplasm and hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei (Fig. 32-14) (157,158). Granular cell, keloidal, myxoid, and sclerotic variants have also been reported, and some tumors are pigmented due to hemosiderin deposition (154,155,159–162).

Figure 32-13 Spindle cell atypical fibroxanthoma. A: Swathes of pleomorphic spindle cells are present, with some background collagen. Some tumors of this type show relatively monomorphic cytologic features. B: Immunohistochemistry demonstrates strong positivity in the cytoplasm of the spindle cells for smooth muscle actin. Desmin was negative (not shown).

Figure 32-14 Clear cell atypical fibroxanthoma. The atypical cells exhibit abundant clear cytoplasm in this variant.

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic (147,163) and immunohistochemical (118,164) studies suggest that the progenitor cell is an undifferentiated mesenchymal cell capable of showing histiocytic, fibroblastic, and myofibroblastic differentiation.

Differential Diagnosis. Although the features of this tumor are often characteristic, it is important to perform immunohistochemistry to exclude other malignancies, in particular melanoma, leiomyosarcoma, and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The possibility of a metastasis should always be considered. In our laboratory, a broad panel of markers is applied, with an expected profile of negative staining for desmin, epithelial, and melanoma markers. Positivity with CD68 is generally present (Fig. 32-15), with frequent SMA positivity. Negative staining for desmin helps to exclude leiomyosarcoma in cases of actin positivity. Although desmin positivity has been reported in AFX, such lesions might be better regarded as leiomyosarcoma, particularly if staining is extensive or intense (165). Vimentin, although expected to be positive, has little discriminatory value. CD10 is usually strongly expressed in AFX but has low sensitivity, being also seen in some melanomas and carcinomas (151,166). Despite initial hopes, neither CD163 nor CD117 has proven to be of diagnostic value (167,168). h-Caldesmon has been reported as negative in AFX, but is typically expressed in leiomyosarcoma (165). CD99 expression is frequent in AFX, but not specific (151,169), and it should be noted that some AFXs express Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA) (without evidence of other epithelial marker positivity) and CD31 (155).

Figure 32-15 Clear cell atypical fibroxanthoma. CD68 is typically positive in all forms of AFX.

Principles of Management. Complete local excision should be performed, although recurrences are rare even with incomplete removal (154).

Pleomorphic Dermal Sarcoma

Clinical Summary and Histopathology. A number of tumors are encountered that show features of AFX, but with deeper extension or additional adverse features. The term pleomorphic dermal sarcoma or dermal sarcoma not otherwise specified (NOS) has been suggested for these lesions (170). The presence of perineural, lymphovascular invasion or prominent infiltration of subcutis or beyond has been considered as unacceptable for a diagnosis of AFX (155). Lesions showing deep or extensive invasion of subcutis or adverse features listed earlier have more aggressive behavior, with higher rates of recurrence, and might be considered to represent a superficial form of malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

Principles of Management. Wide local excision and close follow-up of these lesions are indicated.

Malignant

These are fully malignant tumors, with frequent capacity for metastasis and for causing death.

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

Clinical Summary. The concept of malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) (171–173) has generally fallen into disrepute, with many authorities considering that the tumor is neither of histiocytic origin nor a specific entity (1). A large number of theories of histogenesis for these tumors have been proposed and have been recently summarized (174). On the basis of the use of techniques such as immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, and electron microscopy, most MFHs can be recategorized as other types of sarcoma, melanoma, carcinoma, or even lymphoma (1,175–179). The majority of tumors in these categories arise in deep soft tissue, only occasionally reaching the skin by direct growth or metastasis; as such, presentation in the skin is uncommon (180,181). CGH of a large series of tumors showed identical cytogenetic changes in many leiomyosarcomas and lesions classified as MFH, suggesting that many MFHs are leiomyosarcomas that have become too poorly differentiated to be recognized by most standard techniques (182). Recently, array-CGH and transcriptome analysis on 160 soft tissue sarcomas with complex genomics also supported the concept that a proportion of MFH-type lesions are forms of leiomyosarcoma (183).

Despite the best techniques available, a small group of MFH-type tumors apparently show no definable line of differentiation (about 20% of lesions in one practice [174]). These are probably best classified for the most part as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas (174,175,177,184). Myxoid MFH is generally considered to be a myxofibrosarcoma, and giant cell MFH (185,186) probably often represents a form of osteosarcoma or, perhaps, malignant giant cell tumor of soft tissue (187).

Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma was formerly regarded as a subtype of MFH (188) but has been reclassified as a fibrohistiocytic tumor of intermediate grade on the basis of its excellent prognosis (see later) (71,189).

Principles of Management. Complete wide surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy may be used as adjuncts and for palliation. The prognosis is generally poor, especially for incompletely excised and recurrent lesions.

FIBROBLASTIC/MYOFIBROBLASTIC TUMORS

These lesions generally lack the histiocytic differentiation (e.g., presence of giant cells, foam cells, and CD68 reactivity) seen in the so-called fibrohistiocytic tumors described earlier.

Benign

These benign lesions may recur locally, but in general their growth is not destructive and they do not metastasize.

Hypertrophic Scar and Keloid

Clinical Summary. Excessive fibrous tissue deposited in association with scar formation may lead to a hypertrophic scar or keloid. There are important clinical and pathologic differences between these processes, although it has been suggested that they may form a spectrum of changes (190–192). Keloids may become much more prominent than hypertrophic scars, persist, and can extend beyond the original site of injury, with a high rate of recurrence following surgical treatment. However, contractures are not a feature of keloid scars, tending to occur mostly in postburn hypertrophic scars. Keloids occur mainly on the upper chest and arms, head and neck, and especially on the ear. They are uncommon in the periocular region and on the palms, soles, penis, and scrotum (193,194). Keloids mostly affect people in the second and third decades of life, and they are more common in wounds that have been infected or are under excess tension.

There is frequently a history of prior trauma (such as ear piercing), but some keloids apparently arise spontaneously, especially in the presternal region. Dark-skinned individuals are much more susceptible to keloids, and occasional familial cases have been recorded (194).

Histopathology. Hypertrophic scars and keloids both exhibit excess collagen formation with varying numbers of fibroblastic cells. These tend to form nodular, whorled masses, with vertically aligned vessels in hypertrophic scars and reduced vascularity in keloids (194,195). SMA-positive myofibroblasts are characteristically present in hypertrophic scars and scant or absent in keloids. In keloids, hypocellular zones of fibrous tissue contain thickened, glassy, eosinophilic collagen bundles, in contrast to the more cellular nodules in hypertrophic scars (Fig. 32-16A, B).

Figure 32-16 Keloid scar. A: Nodules of spindle cells with abundant collagen are present in the dermis with prominent hyalinization. B: Glassy eosinophilic and hyalinized collagen fibers are interspersed with swathes of fibroblasts.

Pathogenesis. Keloids have been shown to exhibit abnormal fibroblast activity, with increased hyaluronic acid production and increased levels of transforming growth factor β and other cytokines (196). Decreased apoptosis may also play a role, allowing the keloidal fibroblasts to proliferate and produce more collagen (196). Reduced vascular density in keloids compared to that in hypertrophic scars and normally healing scars suggests that hypoxia may also play an important role (194).

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the principal approach to the treatment of hypertrophic scars (197), and intralesional steroids may enhance resolution. Surgery alone may be problematic in some keloids because this may exacerbate the lesions. Keloid treatments include pressure therapy, a variety of topical and intralesional agents, including corticosteroids injection, interferon, laser therapy, radiotherapy, and cryotherapy (197). These treatments may be combined with surgical debulking.

Dermatomyofibroma

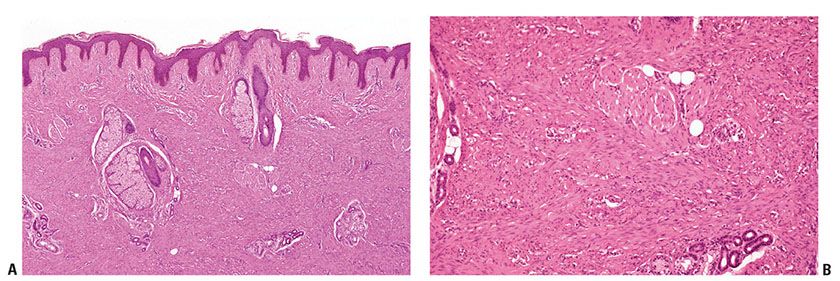

Clinical Summary. Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon plaquelike proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the dermis, occurring mainly in young females, although a wide range of ages may be affected (198). The lesions are typically small, with a variety of sites involved, although the shoulder region and neck are most commonly affected (198–201).

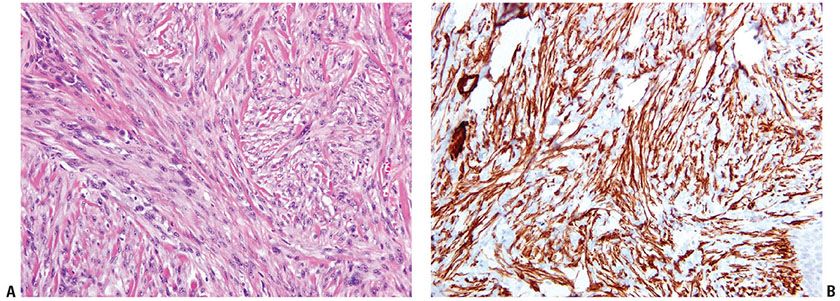

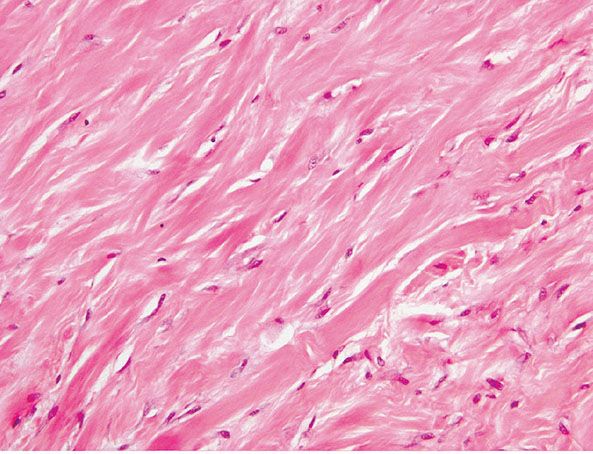

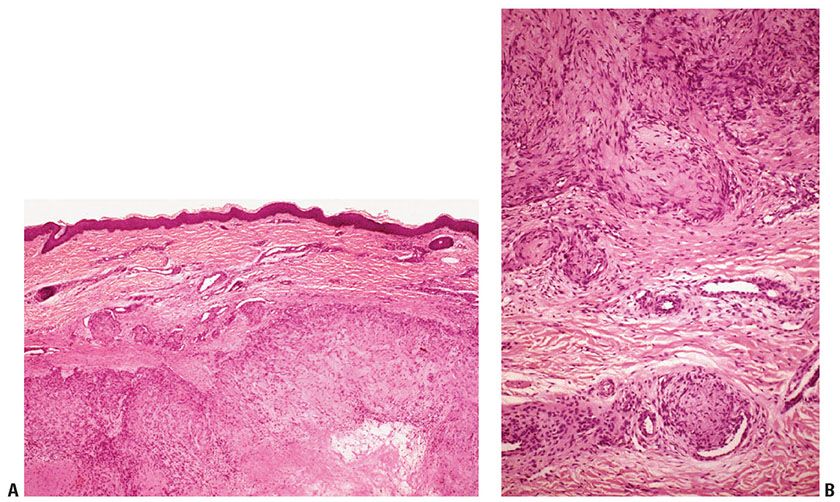

Histopathology. Uniform spindle cells in elongated and intersecting fascicles are arranged mainly parallel to the epidermis to form a well-circumscribed plaque. There is occasional involvement of the subcutis, with sparing of adnexa and papillary dermis (Fig. 32-17A, B) (198,199,202). Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and pigmentation may be seen with increased and fragmented elastin within the lesion. Three cases have recently been reported in adult males on the thigh and trunk that showed red blood cell extravasation associated with dilated capillaries and slit-like spaces, giving a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma (203).

Figure 32-17 Dermatomyofibroma. A: The epidermis shows elongated rete ridges overlying a plaque of increased cellularity that surrounds but does not replace appendages. B: At higher power, the lesion is seen to be composed of uniform spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm that efface the dermis, sparing adnexae.

Pathogenesis. Immunohistochemical reactivity for nonspecific muscle actin, variably for α-SMA, and the ultrastructural features suggest myofibroblastic differentiation (199,202,204,205).

Differential Diagnosis. The orientation parallel to the epidermis of monomorphic spindle cells and their location primarily in the reticular dermis are points of distinction from fibrous histiocytoma. Dermatomyofibroma does not express factor XIIIa or h-caldesmon (202,204). Desmin and S100 are also negative, with only limited CD34 positivity reported (198).

Principles of Management. Conservative local excision is considered adequate treatment, with no recurrence seen in a series of 56 tumors, even when excision was marginal or incomplete (198).

Soft Fibroma (Fibroepithelial Polyp)

Clinical Summary. Soft fibromas, also called fibroepithelial polyps, acrochordons, or skin tags, occur as three types: (a) multiple, 1- to 2-mm, furrowed papules, especially on the neck and axillae; (b) single or multiple filiform, smooth growths in varying locations, up to 5 mm long; and (c) solitary, pedunculated or “baglike” growths, usually about 10 mm diameter but occasionally much larger, most often on the lower trunk (206,207).

Several reports have suggested an association between the presence of soft fibroma and colonic polyps (207–210), diabetes (211–213), and acromegaly (214). The association with colonic polyps, however, has not been confirmed by subsequent reports (215–220).

Histopathology. The multiple small furrowed papules usually show papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and regular acanthosis. Occasionally horn cysts are also present, giving a resemblance to a pedunculated seborrheic keratosis. The epidermis of the filiform, smooth growths shows slight-to-moderate acanthosis and occasionally mild papillomatosis. The connective tissue stalk is composed of loose collagen fibers and often contains numerous dilated capillaries filled with erythrocytes. Nevus cells are found in as many as 30% of the filiform growths, indicating that some of them represent involuting melanocytic nevi (221). The larger pedunculated growths generally show a flattened epidermis overlying loose collagen fibers and mature fat cells in the center (216). In some instances, the fat is prominent, indicating lipofibroma formation (222). Malignancy arising in these polyps is an exceedingly rare phenomenon (223) and probably represents a coincidental occurrence rather than true malignant transformation.

Principles of Management. Lesions are excised for cosmetic purposes.

Pleomorphic Fibroma

Clinical Summary. Pleomorphic fibroma typically presents as a slow-growing exophytic nodule most commonly on the trunk or extremities and rarely at other sites, such as the face and subungual location, of middle-aged to older adults (224–226).

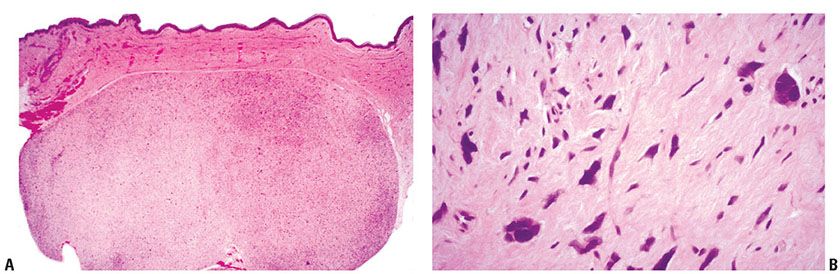

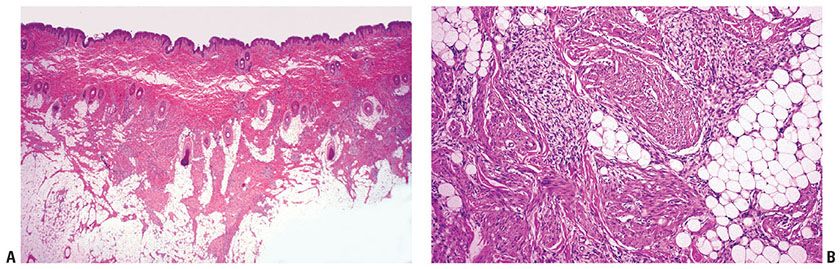

Histopathology. The epidermis is flattened, overlying a circumscribed nodule in the dermis composed of plump mononucleate and multinucleate, spindle-shaped or stellate cells with atypical nuclei and occasional mitoses, distributed sparsely in a fibrous stroma (Fig. 32-18A, B).

Figure 32-18 Pleomorphic fibroma. A: A sharply circumscribed nodule in the dermis and subcutis. B: Spindle cells and giant cells with marked nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromatism in a pale, hyalinized stroma.

Pathogenesis. The tumor cells are variably SMA and CD34 positive, suggesting either myofibroblastic or dermal dendritic cell origin/differentiation (219,224,225,227).

Differential Diagnosis. Dermatofibromas with monster cells are more cellular, and have areas with typical histologic features of dermatofibroma and often acanthotic pigmented epidermis overlying the lesion. In contrast to dermatofibroma, pleomorphic fibroma expresses CD34 (227). AFXs present as rapidly growing, highly cellular lesions composed of pleomorphic, spindle-shaped to epithelioid cells with numerous mitotic figures, which may be atypical. Cases with adipocytes may resemble atypical dermal lipomatous tumor. Pleomorphic fibromas, by contrast, are negative for MDM2 by immunohistochemistry with no demonstrable 12q15/MDM2 amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization (228). Diagnosis by cytology is fraught with danger as the pleomorphic cells in this benign lesion may appear malignant (229).

Principles of Management. Excision is curative and recurrences are rare.

Sclerotic Fibroma (Storiform Collagenoma or Plywood Fibroma)

Clinical Summary. This is an uncommon lesion usually occurring as a small, solitary nodule, but occasionally lesions may be as large as 3 cm diameter (230). Multiple lesions are a marker for Cowden disease (231). A number of cases have been reported in the oral cavity (232).

Histopathology. The tumors are circumscribed and composed of interwoven fascicles of laminated eosinophilic collagen with prominent clefting (Fig. 32-19A, B). Cellularity is low, with inconspicuous nuclei. Occasional cases have been reported containing pleomorphic cells, suggesting a relationship to pleomorphic fibroma (233). Giant cells may be conspicuous in some examples (234). Immunostaining is positive for factor XIIIa, with focal positivity for CD34 (235).

Figure 32-19 Sclerotic fibroma. A: A pale, poorly cellular lesion replaces the dermis with some flattening of overlying rete ridges. B: Clefts are prominent between laminated, hyaline, and highly eosinophilic collagen.

Pathogenesis. On the basis of similar fibrotic changes seen in dermatofibroma and in inflammatory lesions, it has been suggested that sclerotic fibromas may have diverse origins (236,237). The demonstration of ongoing collagen synthesis, rare recurrence, and detection of proliferative activity with immunohistochemistry, however, suggests that the lesions are benign fibroblastic neoplasms (235,238,239).

Principles of Management. Local excision is typically curative, with recurrence exceptional.

Fibroma of Tendon Sheath

Clinical Summary. Fibroma of tendon sheath presents as a slow-growing nodule near tendinous structures, most frequently in the hands and wrists. Other less common sites include feet, elbows, and knees. It is uncertain whether fibroma of tendon sheath is a neoplasm or a reactive process. A clonal chromosomal abnormality, t(2;11) (q31–32;q12), has been demonstrated (240). The identical translocation has been described in collagenous fibroma, raising the possibility of a genetic link (241). A case of multifocal concurrent fibromas of tendon sheath in the hands and feet (242), as well as intra-articular cases (243), has been reported.

Histopathology. The lesion is characterized by nodules largely composed of interlacing bundles of hyalinized, hypocellular fibrous tissue, with occasional more cellular areas of spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 32-20A, B). The more cellular areas may show some degree of pleomorphism, with mitotic figures (244). A characteristic feature is the presence of slitlike vascular channels (245). No foam cells are seen, and multinucleated giant cells are very rare (244).

Figure 32-20 Fibroma of tendon sheath. A: These lesions are poorly cellular, with ill-defined fascicles of bland, myofibroblast-type cells. B: The spindle cells show a smooth muscle–like appearance and are typically actin positive.

Pathogenesis. The cells of fibroma of tendon sheath express SMA. Ultrastructural studies show features of myofibroblastic differentiation (246).

Principles of Management. Treatment is by local excision, with a recurrence rate of 24% (247).

Collagenous Fibroma (Desmoplastic Fibroblastoma)

Clinical Summary. Collagenous fibroma is a rare benign tumor mainly affecting men. It typically involves subcutis or skeletal muscle, but occasionally it primarily involves the dermis (248–250). Tumors are usually small (1 to 4 cm diameter), but examples up to 20 cm in diameter have been reported (251). A number of cases have been recorded in the oral cavity (252,253).

Histopathology. Tumors are circumscribed, ovoid masses that may be lobulated and are composed of dense, paucicellular collagenous tissue with scattered spindle cells without mitotic activity. These show features of myofibroblasts ultrastructurally (254–256). A fascicular growth pattern is absent, and areas reminiscent of a keloid may be seen (Fig. 32-21). Focal myxoid change may be present with inconspicuous blood vessels (251). The tumor cells variably express α-SMA and are negative for desmin, EMA, S100 protein, and CD34 (251). Cytogenetic studies performed in a number of cases have shown a t(2;11) translocation, suggesting a relationship to fibroma of tendon sheath, which has shown the same abnormality (257–259).

Figure 32-21 Desmoplastic fibroblastoma/collagenous fibroma. Thick bands of hyalinized, eosinophilic collagen are present, giving an appearance resembling a keloid.

Principles of Management. Excision is curative, with no malignant transformation recorded.

Nodular Fasciitis

Clinical Summary. Nodular fasciitis is a rapidly growing benign soft tissue lesion. It usually presents as a solitary, sometimes tender subcutaneous nodule that reaches its ultimate size of 1 to 5 cm within a few weeks. The lesions tend to regress, even if incompletely excised, usually within a few months (260). Although the arm is the most common site, lesions may occur in any subcutaneous area. Nodular fasciitis occurs in all age groups but is more common in young adults, with an equal sex distribution. The cause is unknown. Although trauma does not seem to play a role, the general view is that nodular fasciitis represents a reactive fibroblastic and vascular proliferation.

Histopathology. Nodular fasciitis usually occurs in the subcutis, less often in muscle, and rarely in the dermis. A prominent feature is the infiltrative growth pattern along fibrous septa of the subcutis, resulting in poor demarcation. The nodule consists of immature spindly myofibroblasts and fibroblasts growing haphazardly in vascular, myxoid stroma, presenting a “tissue culture–like” pattern (Fig. 32-22A, B). The vascular component includes well-formed capillaries and slitlike spaces with extravasation of red blood cells. The fibroblasts may show numerous mitoses, which are not atypical. Multinucleate, osteoclast-like giant cells are frequently present. In some instances, degenerate muscle fibers simulate multinucleate giant cells (261). A lymphocytic infiltrate is often present, mainly at the periphery of the nodule (262). In older lesions, the fibroblasts appear more mature, showing a more compact arrangement of spindle cells with increased production of collagen (263). It has been reported that USP6 rearrangements with the formation of the fusion gene MYH9–USP6 occur in most examples of nodular fasciitis, but USP6 rearrangements are absent in its histologic mimics in soft tissue, including desmoid-type fibromatosis, fibrosarcoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Therefore, USP6 FISH may be a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis (264).

Figure 32-22 Nodular fasciitis. A: Plump spindle cells are arranged in varied cellularity in a loosely structured, vascular stroma. B: Plump spindle cells with ovoid, vesicular nuclei and scattered mitoses are embedded in a loosely structured stroma with capillaries and scattered erythrocytes.

Dermal fasciitis is a rare variant arising within the dermis, usually occurring on the limbs and trunk of young adults (265), but also occurring in the head and neck region (266–270). Only one tumor recurred locally. No lesion metastasized (265). Postoperative/posttraumatic spindle cell nodule has also been described as the dermal analog of nodular fasciitis (271). Another variant, intravascular fasciitis (272), occurs within vessel walls. Proliferative fasciitis appears to be related to nodular fasciitis but includes giant cells resembling ganglion cells, similar to those of proliferative myositis. These show abundant, irregularly outlined, basophilic cytoplasm with one or two large vesicular nuclei and a prominent nucleolus (273,274). Ki67 has not been found to be useful in discriminating the lesion from a sarcoma (275).

Pathogenesis. The spindle cells in nodular fasciitis have the ultrastructural features of myofibroblasts (276). As in other myofibroblastic lesions, the cells are immunoreactive for SMA and muscle-specific actin (MSA) but not for desmin (277).

Differential Diagnosis. The presence of numerous large, pleomorphic fibroblasts and the infiltrative type of growth may suggest a malignancy such as sarcoma. In addition to rapid growth and tenderness, however, the combination of fibroblastic and vascular proliferation is the most helpful diagnostic feature of nodular fasciitis. Other findings suggesting the diagnosis are the presence of a mucoid ground substance and an inflammatory infiltrate, especially near the margin of the lesion. Recurrence of a lesion originally diagnosed as nodular fasciitis should spur a careful reappraisal of the clinical and histologic findings (261).

Cranial fasciitis of childhood is considered an unusual variant of nodular fasciitis of uncertain etiology. It occurs in infants and children as a rapidly growing mass in the subcutaneous tissue of the scalp that extends into the underlying cranium. In some cases, the lesion extends through the cranium to involve the dura (278). No recurrence has been reported after excision of the mass with resection or curettage of the underlying bone (278,279). The histologic features closely resemble those of nodular fasciitis. An origin in one of the deep fascial layers of the scalp appears likely (278).

Principles of Management. The lesion follows a benign course, and recurrences are infrequent.

Ischemic Fasciitis

Clinical Summary. This condition is also known as atypical decubital fibroplasia and often occurs at sites of long-standing pressure, typically in the elderly (280,281). The resultant ischemia is believed to induce formation of a reactive fibroblastic proliferation that may mimic nodular or proliferative fasciitis or even a sarcoma. Not all cases are associated with immobility, and some appear trauma related (282). The process extends through dermis and into subcutis and sometimes underlying tissue, including skeletal muscle, often abutting bony prominences.

Histopathology. Reactive fibroblastic tissue is present associated with foci of necrosis and repair. Atypical reactive fibroblasts are seen with a proliferation of fine vessels, and ulceration may be present (Fig. 32-23A, B) (281). A myofibroblastic origin in at least some of the cells is supported by finding actin and or desmin staining in a number of cases studied (282).

Figure 32-23 Ischemic fasciitis. A: Fibrin deposition and granulation tissue are present in this lesion excised from the greater trochanter of an elderly, bed-ridden man. B: Dilated vessels and reactive stromal cells are seen at high power. The degree of atypia may raise the possibility of a sarcoma at times.

Principles of Management. Local excision is usually curative if the predisposing factor is removed.

Myofibroma/Myofibromatosis

Clinical Summary. Myofibroma is a benign neoplasm that can present as solitary or multiple lesions. The majority of tumors are solitary, measuring between 0.5 and 7.0 cm in size. The nodules are most commonly confined to the dermis, subcutis, and skeletal muscle of the head, neck, and trunk, but any site may be affected. In infantile myofibromatosis, multiple tumors may also develop in bones and viscera in addition to skin involvement, causing death in rare cases (283–285). Death may occur in the first few months of life, usually from cardiopulmonary or gastrointestinal complications, but in survivors and in those with superficial myofibromatosis, spontaneous involution of the lesions usually takes place, often within the first year of life. Involution may be mediated by apoptosis or overgrowth of its own vascular supply (286,287). In adults, the tumors are solitary and superficial, and show no tendency to regress (288,289). Familial cases of infantile myofibromatosis are believed to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner (290). Myopericytoma is a term that has been introduced to describe a spectrum of tumors typified by a hemangiopericytoma-like vascular architecture and features of perivascular myoid (myopericytic) differentiation. The term has been used to describe myofibroma, myopericytoma, and glomangiopericytoma (291, also see Myopericytoma, Chapter 33 Vascular tumors).

Histopathology. Most tumors have a characteristic biphasic growth pattern. The lesions consist of nodular dermal aggregates of plump spindle cells resembling smooth muscle cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in short fascicles, sometimes with areas of hyalinization (292) (Fig. 32-24A, B) surrounding a central, hemangiopericytoma-like component where less-differentiated rounded cells with scant cytoplasm are arranged around irregularly shaped, thin-walled blood vessels. There is no atypia or pleomorphism. The stroma may appear mucoid in the less cellular areas (293). Foci of necrosis and calcification may be present centrally. In some cases, the distribution of the two components is reversed; that is, the hemangiopericytoma-like areas are situated peripherally. Other lesions may show a predominance of myoid or hemangiopericytomatous elements.

Figure 32-24 Myofibroma. A: Circumscribed dermal nodules of varied size, with hyalinization in the center of the largest nodule. B: The nodules consist of fascicles of plump spindle cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, some of which indent the walls of blood vessels.

Pathogenesis. Solitary and multifocal myofibromas stained positively for SMA in 95% and 92% of cases, MSA in 75% and 50% of cases, and desmin in 10% and 14% of cases, respectively, in one large series (294). The cells are believed to be myopericytic in origin (289,295).

Principles of Management. Patients should be evaluated for the possibility of multiple tumors. The treatment of choice is early conservative surgery to minimize functional and/or aesthetic damage. Complete tumor excision is not always possible (296). Most patients in one large study were treated with complete or partial excision. There were no recurrences after treatment (294).

Fibrous Hamartoma of Infancy

Clinical Summary. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy usually occurs as one or, rarely, two subcutaneous nodules that may be present at birth or develop during the first 2 years of life (297–300). After an initial period of growth, there is no further increase in the size of the nodule. There is a predilection for boys, with male-to-female ratio of up to 2.6:1 (300,301). These lesions present in a wide range of locations, most commonly the axilla, upper arm, upper trunk, inguinal region, and external genitalia (300). A case with t(2;3) (q31;q21) chromosomal translocation was described (302).

Histopathology. The nodule consists of immature spindly myofibroblasts and fibroblasts growing haphazardly in a vascular, myxoid stroma, presenting a “tissue culture -like” pattern (Fig. 32-25A, B) (297,298). The fibrous component varies in cellularity, pattern, and amount and may resemble granulation tissue, deep fibrous histiocytoma, or fibromatosis in some areas (301). The spindle cells in the fibrous trabeculae express actin (300).

Figure 32-25 Fibrous hamartoma of infancy. A: Trabeculae of varied thickness intersect lobules of fat in the subcutis. B: The trabeculae are composed of immature spindle cells arranged in loosely structured myxoid areas and more densely collagenous tissue.

Principles of Management. Complete local excision is usually curative, and the recurrence rate is low (303).

Juvenile Hyaline Fibromatosis

Clinical Summary. This is a rare, autosomal recessively inherited disorder. It starts in early infancy with flexural contractures and innumerable skin papules and nodules that gradually increase in size, with osteolytic bone lesions and gingival hyperplasia. Wartlike papillomatous lesions may occur in the perianal region. The largest nodules are usually seen on the scalp and around the neck. Juvenile hyaline fibromatosis has been reported in association with skull and encephalic abnormalities and in the hand of an adult (304). Infantile systemic hyalinosis is believed to be a severe form of the disease, with widespread visceral involvement and an invariably fatal outcome (305). Some have suggested the unifying term of hyaline fibromatosis syndrome to encompass both entities (306).

Histopathology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree