Figure 14-1 Granuloma annulare. Raised pink papules in an annular configuration in the antecubital fossa.

A correlation between generalized papular granuloma annulare, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia has been observed by several authors, with additional rare reports suggesting an association with thyroid disease (2,3,24,25). Granuloma annulare has been reported in at least 60 patients with HIV or AIDS, with a greater incidence of generalized disease in this population (26–30). Granuloma annulare–like lesions have also been reported to develop at sites of resolved herpes zoster (31,32) and, occasionally, in association with tattoos (33), necrobiosis lipoidica (34), and sarcoidosis (35).

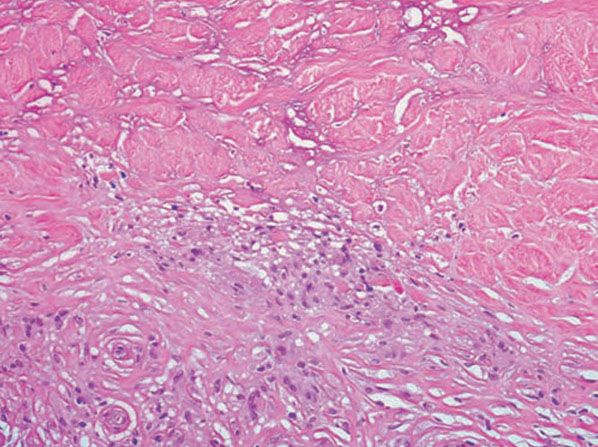

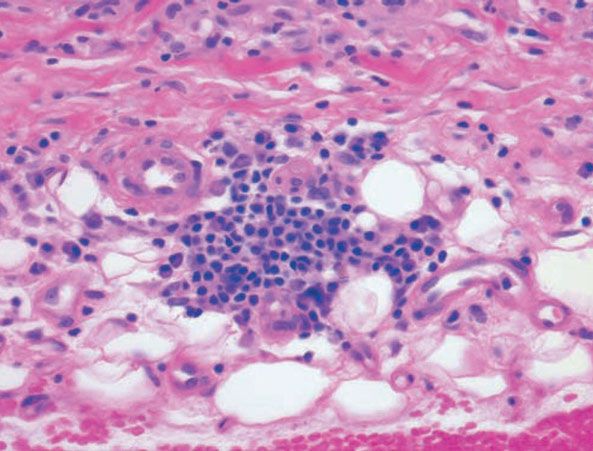

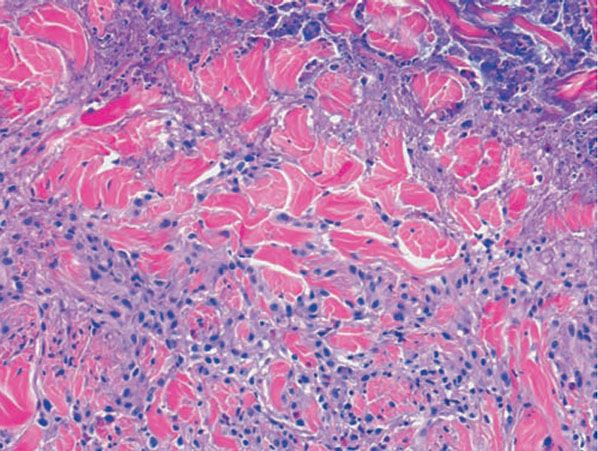

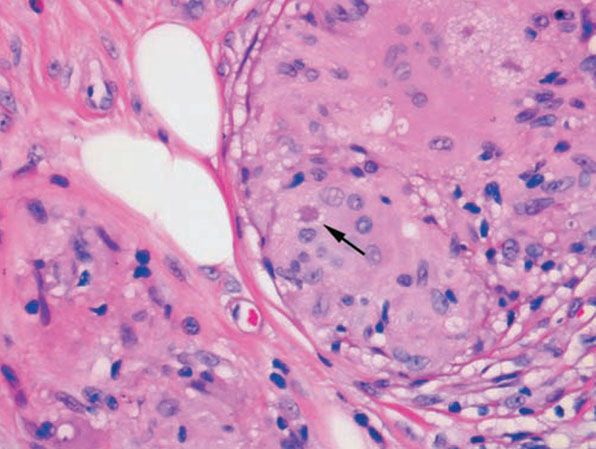

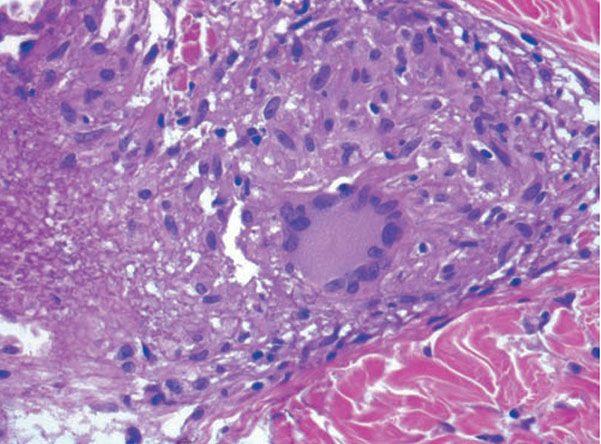

Histopathology. Histologically, granuloma annulare shows an infiltrate of histiocytes and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes that is usually sparse. The histiocytes may be present in an interstitial pattern without apparent organization or in palisades surrounding areas with prominent mucin (Figs. 14-2 to 14-5). Patterns between these two extremes occur, and a single biopsy may show interstitial, slightly palisaded, and well-palisaded histiocytes. Although degenerated collagen or small quantities of fibrin may be present (36), increased mucin is the hallmark of granuloma annulare. Occasionally, sections will not reveal increased mucin, particularly those lacking a palisaded arrangement of histiocytes. In biopsies with well-developed palisades, the central mucinous area is commonly accompanied by a few nuclear fragments or neutrophils. Plasma cells are present rarely. A sparse infiltrate of eosinophils is seen in approximately half of cases, and occasional biopsies show abundant eosinophils (37,38). Multinucleated histiocytes are present more often than not, but they are usually few and often subtle. They can occasionally be seen to have engulfed short, thick, blue-gray elastic fibers (39). The histiocytic infiltrate is usually present throughout the full thickness of the dermis or the middle and upper dermis, but occasionally, just the superficial or the deep dermis is involved (40). Mitotic figures are usually rare (fewer than 1 per 10 high-power fields), but may be as frequent as 7 per 10 high-power fields in rare examples (41).

Figure 14-2 Granuloma annulare. A palisade of histiocytes surrounds mucin in the upper dermis.

Figure 14-3 Granuloma annulare. Histiocytes surround mucin, which shows a feathery blue appearance, and a few fragments of neutrophils.

Figure 14-4 Granuloma annulare. Interstitial pattern granuloma annulare exhibits histiocytes between collagen bundles and perivascular lymphocytes.

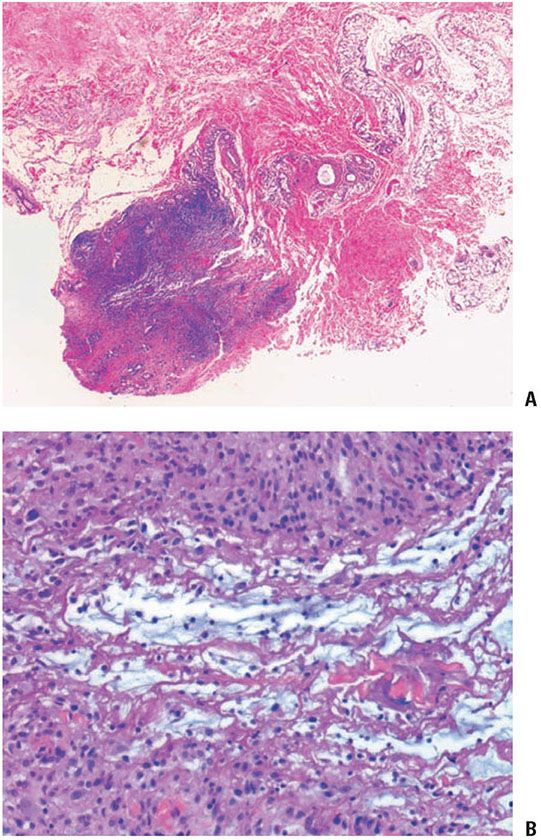

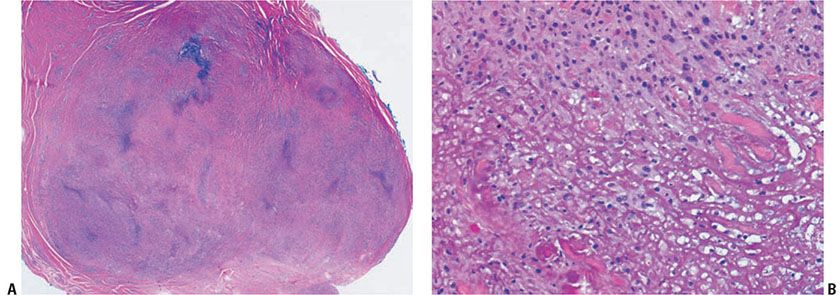

Figure 14-5 Deep granuloma annulare. A: A well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule shows palisaded histiocytes surrounding mucin and fibrinoid material. B: Histiocytes in a palisade surround mucin and fibrinoid material.

Rare examples of granuloma annulare show aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes, usually with some giant cells and a rim of lymphoid cells, which resemble the granulomas of sarcoidosis (35,36,40). These usually differ from sarcoidal granulomas, however, by showing poorer circumscription and by lacking asteroid bodies. Vascular changes in granuloma annulare are variable but generally inconspicuous (42). Among the variants of granuloma annulare mentioned, the usual histologic picture of palisaded and interstitial pattern is found in the generalized form (4). Occasionally, there is a band of histiocytes and giant cells in the superficial dermis with perivascular lymphocytes (4). An interstitial pattern predominates in the erythematous and patch variants (10,11). In perforating granuloma annulare, at least part of the palisading granulomatous process is located superficially and is associated with disruption of the epidermis (5,7,8).

The subcutaneous nodules of deep granuloma annulare usually show large histiocytic palisades surrounding mucin and degenerated collagen (Fig. 14-5). These central, degenerated foci exhibit a pale appearance (43); however, examples in which mucin was not apparent or in which the central area appeared more fibrinoid have also been reported (19,20). Thus, subcutaneous granuloma annulare may be histologically indistinguishable from rheumatoid nodule, an appearance that has led to the term pseudorheumatoid nodule.

Pathogenesis. The cause of granuloma annulare is unknown. Possible precipitating events in small subsets of patients have included insect bites, warts, erythema multiforme, herpes zoster, exposure to sunlight, hepatitis B vaccine, and tuberculin skin tests (44–47). There is likely an increased incidence and increased disease severity in patients with diabetes mellitus. Thrombi or vasculitic changes have been noted in some examples, and it is possible that what we term granuloma annulare may represent a variety of disease processes.

Electron microscopic examination reveals degeneration of both collagen and elastic fibers in granuloma annulare (36). The macrophages (histiocytes) show a high content of primary lysosomes and considerable cytoplasmic activity with release of lysosomal enzymes into the extracellular space (48). Synthesis of types I and III collagen also occurs, probably as a reparative response (49). A cell-mediated immune response also appears to be involved, marked by prominent activated helper T cells (50–52). One immunoperoxidase study of the histiocytic population showed staining for lysozyme but not for other macrophage markers such as HAM 56 or CD-68 (53). Another demonstrated positivity for these two markers (41).

Blood vessel deposits of immunoglobulin M and the third component of complement (C3) have been observed by some investigators (51), but others have found them only rarely (54) or not at all (55). Thus, the existence of an immune complex vasculitis in granuloma annulare (51) appears unlikely.

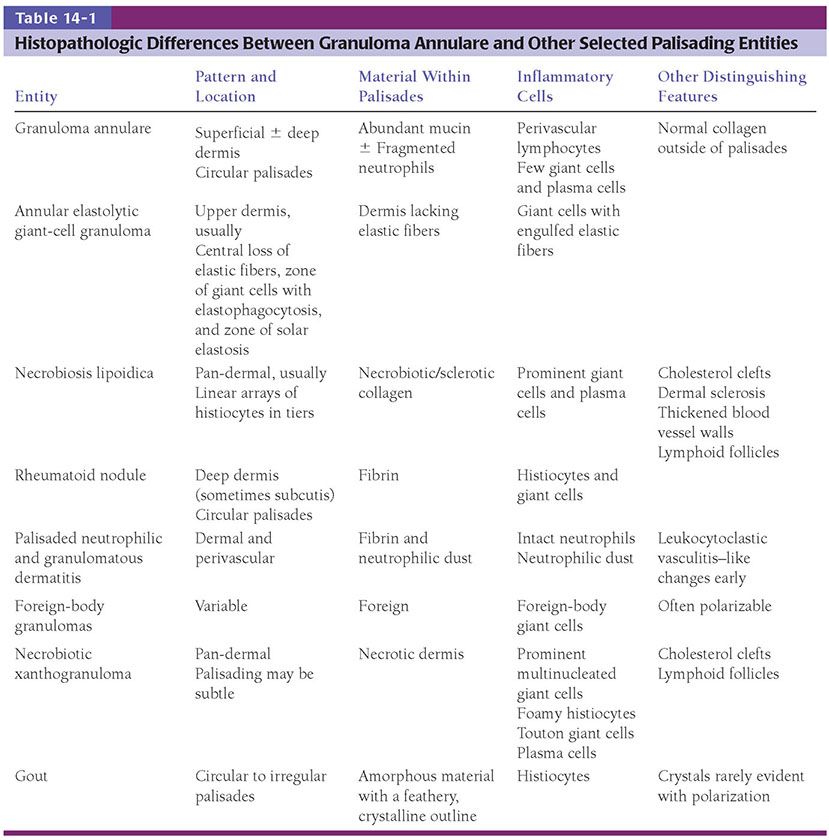

Differential Diagnosis. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica may resemble one another histologically. Although much has been written about the difficulty of separating these disorders histologically (42), the distinction can be accomplished clinically in most circumstances (56). Furthermore, although it is true that histologic distinction may be impossible, usually it can be accomplished by using the criteria in Table 14-1. Other palisading granulomas (e.g., to foreign material) can mimic granuloma annulare (see Table 14-1) (57).

The interstitial type of granuloma annulare, in which palisades of histiocytes are not well developed, is less likely to be confused with necrobiosis lipoidica. This pattern is more likely to be mistaken for a process that can also show a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate, such as the inflammatory stage of morphea, but the subtle presence of histiocytes in an interstitial pattern usually allows for a diagnosis of granuloma annulare. Mycosis fungoides can have a granulomatous infiltrate with a granuloma annulare–like pattern (58,59). Such examples of this cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can usually be recognized by a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that is more dense around the superficial plexus than around the deep one, by a lichenoid component to the infiltrate and, occasionally, by the presence of intraepidermal lymphocytes. The interstitial type of granuloma annulare may also resemble a xanthoma. Distinction is usually possible because in granuloma annulare a foamy appearance to the histiocytes is either completely lacking or very subtle; in xanthoma, at least some of the histiocytes are foamy. In addition, granuloma annulare tends to show an obvious perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, whereas most xanthomas do not (60). Drug reactions may also mimic granuloma annulare, but these usually show interface changes that allow for their distinction (61). Rarely, infection with Mycobacterium marinum may have few neutrophils and may produce a histologic picture resembling interstitial granuloma annulare (62). Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) may represent a variant of granuloma annulare or be a closely related entity. There may be associated arthritis. IGD is more strongly associated with underlying rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory/systemic autoimmune diseases. A variety of clinical lesions have been reported in IGD and/or similar conditions. These range from linear and “ropelike” on the trunk to erythematous patches, plaques, and papules that are sometimes annular (63–68).

Differentiation of subcutaneous granuloma annulare from a rheumatoid nodule is not always possible on histologic grounds, but subcutaneous granuloma annulare is more likely than rheumatoid nodule to show prominent mucin and less likely to show foreign-body giant cells or prominent stromal fibrosis or abundant fibrin (43).

Finally, it should be remembered that granuloma annulare and other palisading granulomas may be simulated by epithelioid sarcoma, a lesion that may also contain mucin. Clues to epithelioid sarcoma include ulceration, cytologic atypia, necrotic foci that include necrotic epithelioid cells, and history of recurrence. Although atypia tends not to be striking, the epithelioid cells in epithelioid sarcoma usually show more nuclear hyperchromasia and pleomorphism, more mitotic figures, larger size, and redder cytoplasm than do the histiocytes of granuloma annulare (69). Immunohistochemically, epithelioid sarcoma can be distinguished from granuloma annulare by positivity for epithelial membrane antigen and keratins and loss of INI1 (70). Whereas a variety of keratins may be present in epithelioid sarcoma, the most common is cytokeratin 8/CAM 5.2, present in 94% of cases (71).

Principles of Management. Granuloma annulare, especially if asymptomatic, does not need to be treated, particularly since lesions may spontaneously resolve. If a patient desires treatment, first-line medications include topical and intralesional corticosteroids for localized disease, and a variety of treatments ranging from phototherapy to antimalarials, anti-inflammatory antibiotics, retinoids, and systemic immunosuppressive agents for more widespread disease.

ANNULAR ELASTOLYTIC GIANT-CELL GRANULOMA

Clinical Summary. Annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma is the name that is currently in vogue for a condition with unclear nosologic status, and it is uncertain whether it is truly distinct from granuloma annulare (72–74). It almost always occurs on sun-exposed skin, such as the face, neck, dorsum of hand, forearm, and arm, hence the previous name actinic granuloma (75,76) (Fig. 14-6). The appearance of lesions after prolonged tanning bed use has been reported (77). However, there are a few reports of similar lesions involving sun-protected sites (78–81). The lesions clinically resemble granuloma annulare. They are typically large, somewhat annular plaques. The border may be serpiginous and is slightly raised, and pearly to red-brown. The central zone may show depigmentation and/or atrophy. Smaller papules may also occur, and lesions may be solitary, few, or numerous (75,82,83). Other names under which these lesions have been described include atypical necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp (84), Miescher granuloma of the face (83), granuloma multiforme (82), and actinic granuloma of O’Brien. A possibly related process occurs on the conjunctiva (85).

Figure 14-6 Annular elastolytic granuloma. Annular pink plaques, with somewhat serpiginous borders, of the forehead.

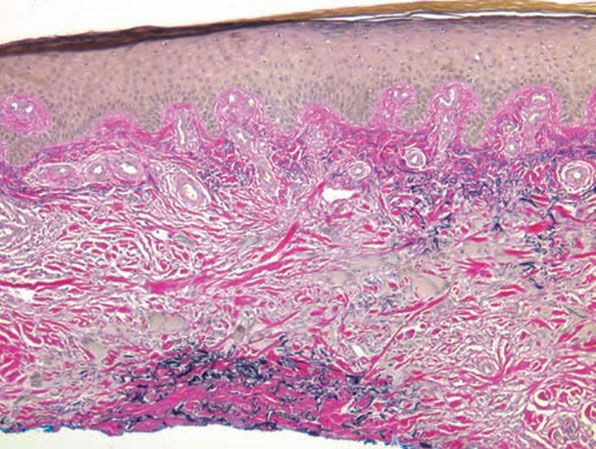

Histopathology. The histologic features are best appreciated in a radial biopsy that contains the central zone, the elevated border, and the skin peripheral to the ring (75,82,83). The central zone shows the hallmark of the disease, that is, near or total absence of elastic fibers, best appreciated with an elastic tissue stain (e.g., Verhoeff-van Gieson) (Figs. 14-7 to 14-9). The collagen in this zone may show horizontally oriented fibers, producing a slight scar-like appearance (Fig. 14-7). By contrast, the zone peripheral to the annulus shows an increased amount of thick elastotic material with the staining properties of elastic tissue. The transitional zone at the raised border shows a granulomatous infiltrate with either of the patterns seen in granuloma annulare, that is, histiocytes arranged interstitially between collagen bundles or, less commonly, in a palisade. Occasionally, there are contiguous epithelioid histiocytes in small clusters. Multinucleated histiocytes are conspicuous, usually being large and containing as many as a dozen nuclei, mostly in haphazard arrangement, but sometimes in ringed array. Elastotic fibers are present adjacent to and within the giant cells (Fig. 14-8). Asteroid bodies that stain like elastic fibers may be found in the giant cells (83). The infiltrate also contains lymphocytes and often some plasma cells. Mucin is inapparent.

Figure 14-7 Annular elastolytic granuloma. Multinucleated histiocytes at left abut connective tissue at the center of the lesion that is slightly fibrotic; mucin is not apparent.

Figure 14-8 Annular elastolytic granuloma. Some multinucleated histiocytes have ingested blue-gray elastic fibers.

Figure 14-9 Annular elastolytic granuloma. Elastic tissue stain shows absence of elastic fibers in the center of the lesion.

Differential Diagnosis. The principal differential diagnosis is granuloma annulare, which may in fact be an artificial distinction. Because engulfment of abnormal elastic fibers can also occur in granuloma annulare (39) as well as in other granulomatous processes, it has been argued that the elastophagocytosis of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma does not qualify it as a distinct entity (73). Although some elastolysis has also been described in granuloma annulare (82), it is the complete loss of elastic tissue in the central zone that has been used as the primary basis for separating the diseases. Other features that have been evoked for distinguishing them are the presence of larger and more numerous giant cells, the absence of mucin in annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma (75,86), and sparing of areas that lack elastic tissue, such as scars (81).

Necrobiosis lipoidica differs by the lack of a central zone of elastolysis and the presence of degenerated collagen, sclerosis, and, in some circumstances, lipids and vascular changes. Furthermore, annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma involves mostly the upper and middle dermis, whereas necrobiosis lipoidica tends to affect the entire dermis and sometimes the subcutis. Foreign-body granulomas generally have more distinct collections of epithelioid histiocytes, lack zonation in density of elastic fibers, and often have identifiable foreign material.

Principles of Management. This condition is chronic and generally responds poorly to topical/intralesional corticosteroids and ultraviolet light treatment; there exist individual case reports of success with oral hydroxychloroquine and anti-inflammatory antibiotics, including dapsone (87).

NECROBIOSIS LIPOIDICA

Clinical Summary. Necrobiosis lipoidica is an idiopathic disorder typified by indurated plaques of the shins (Fig. 14-10). In 1966, in a large series, Muller and Winkelman (88) reported that two-thirds of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica had overt diabetes at the time of diagnosis. Of the rest, all but 10% developed diabetes within 5 years, had abnormal glucose tolerance, or had a history of diabetes in at least one parent. In a more recent series, only 11% of patients had diabetes at presentation, with an additional 11% developing diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance over 15 years (89). Of all patients with diabetes, fewer than 1% develop necrobiosis lipoidica (89). Some reports have suggested that necrobiosis lipoidica heralds a more rapid progression of diabetes in patients with that disorder, and may suggest an increased likelihood of end-organ microvascular damage, including retinopathy and earlier renal dysfunction (90).

Figure 14-10 Necrobiosis lipoidica. Waxy, red-brown plaque with central fine telangiectasia on the shin.

In well-developed necrobiosis lipoidica, one observes one or several sharply but irregularly demarcated patches or plaques, usually on the shins (91). Usually they are bilateral, and the condition is more often present in women. The lesions appear yellow-brown in the center and more actively inflamed with red, orange, or violaceous erythema at the periphery. Whereas the periphery of the lesions may show slight induration, the center of the lesions gradually becomes atrophic, shows telangiectases, and may ulcerate. When lesions first begin, red-brown papules can be observed. In addition to the shins, lesions may be present elsewhere on the lower extremities, including the ankles, calves, thighs, popliteal areas, and feet. In about 15% of the cases, lesions are present also in areas other than the legs, especially on the dorsa of the hands, fingers, and forearms. Rarely, the head and abdomen are affected. Necrobiosis lipoidica with lesions exclusively outside the legs is extremely rare; it is reported to occur in 1% of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica (88).

Lesions located in areas other than the legs may appear raised and firm and may have a papular, nodular, or plaque-like appearance without atrophy. Clinically, they may resemble granuloma annulare (88). Involvement of the scalp by large, atrophic patches occurs occasionally. This is usually seen in association with lesions on the shins and elsewhere (92,93) but also, rarely, in isolation (94–96).

In rare instances, transfollicular elimination of necrotic material takes place in necrobiosis lipoidica, producing small hyperkeratotic plugs within a plaque (97,98). Necrobiosis lipoidica occasionally coexists with sarcoid (99) or granuloma annulare (34). Rare examples of squamous cell carcinoma arising in lesions of necrobiosis lipoidica have been reported (100,101).

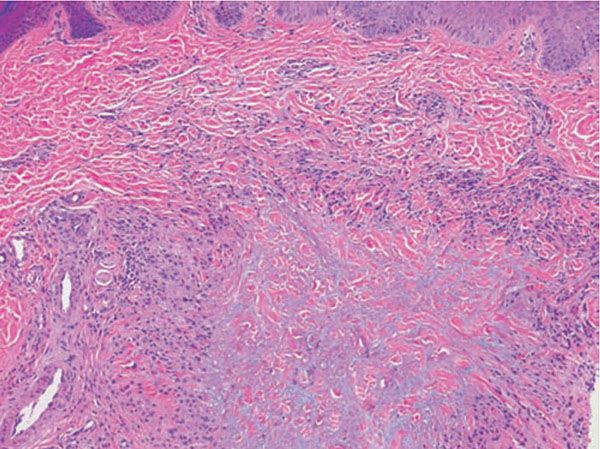

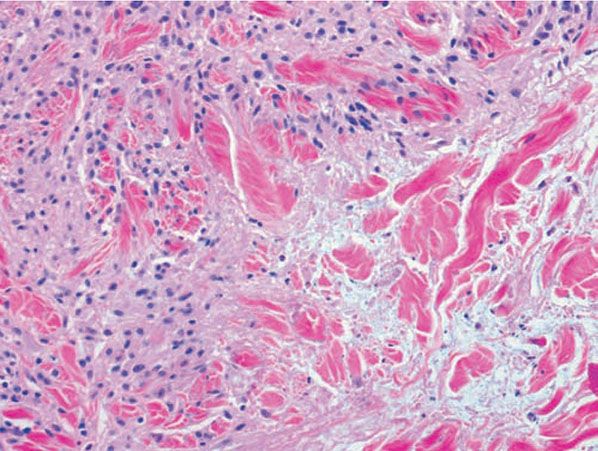

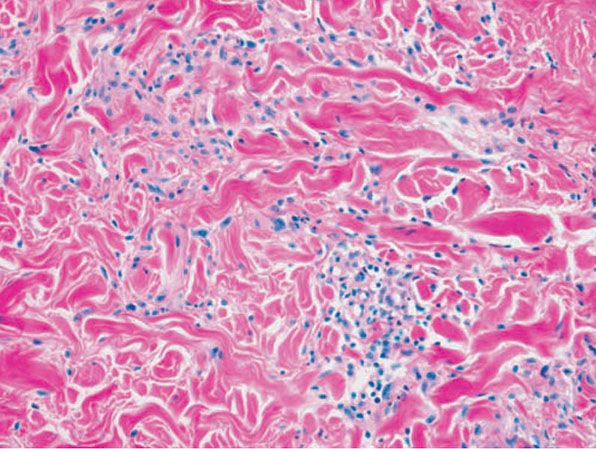

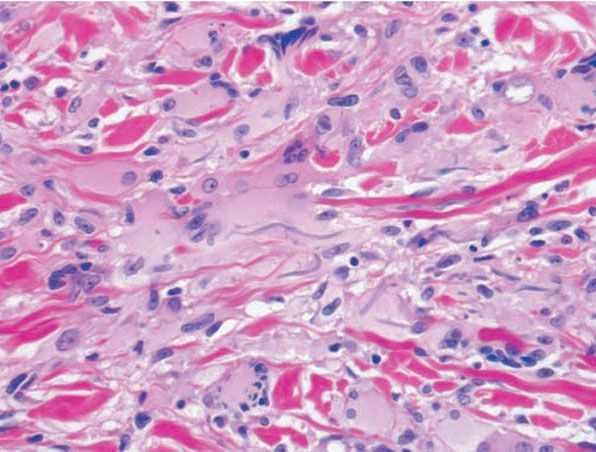

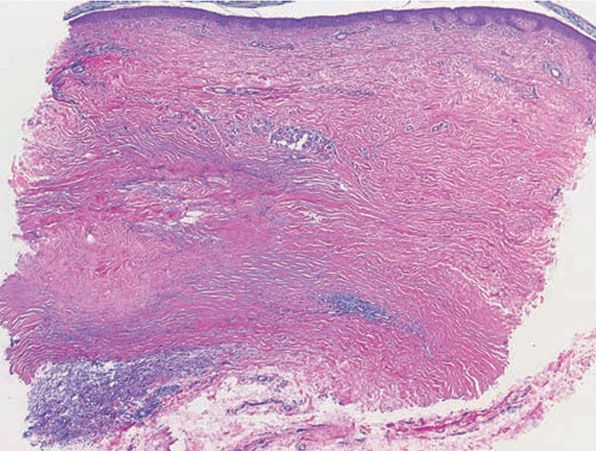

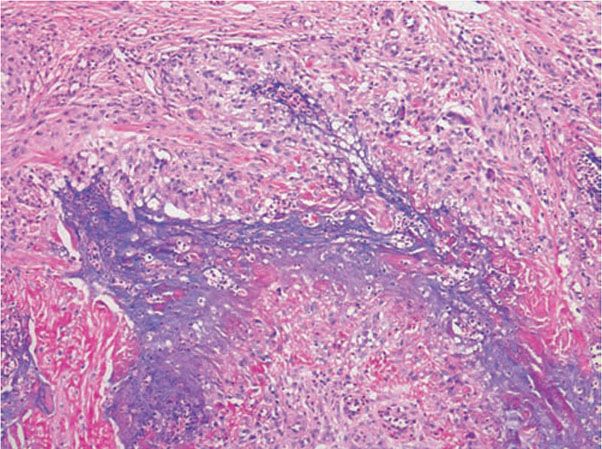

Histopathology. Usually, the entire thickness of the dermis or its lower two-thirds is affected by a process that exhibits a variable degree of granulomatous inflammation, degeneration of collagen, and sclerosis (Figs. 14-11 and 14-12). Histologic changes of necrobiosis lipoidica may be seen in subcutaneous septae (102,103). Occasionally, only the upper dermis is affected (40,42,56,88). The epidermis may be normal, atrophic, or hyperkeratotic. In some instances, the surface of the biopsy shows ulceration. The granulomatous component is usually conspicuous, and the histiocytes may or may not be arranged in a palisade. Occasionally, there are just a few scattered epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells. The latter picture is more likely to occur in sections in which sclerosis is extensive, and occasionally in such biopsies several sections must be examined before a granulomatous component becomes apparent. Giant cells are usually of the Langhans- or foreign-body type; occasionally, Touton cells or asteroid bodies (104) are seen. If the histiocytes are arranged in a palisade, the palisades tend to be somewhat horizontally oriented and/or vaguely tiered. Occasionally, histiocytes may be seen completely to encircle altered connective tissue, particularly degenerated collagen, but, more commonly, altered connective tissue is incompletely surrounded by histiocytes. This alteration of connective tissue has also been referred to as “necrobiosis.” The altered collagen appears different from normal collagen by having a paler, grayer hue and by appearing more fragmented and haphazardly arranged; it may also appear more compact or smudged (Fig. 14-12). Areas of sclerosis with a diminished number of fibroblasts can be seen. A clue to the presence of sclerosis can be found by looking at the edges of the biopsy specimen, which tend to be straight with less of the inward retraction of the dermis ordinarily associated with punch biopsies (Fig. 14-11). Increased mucin is usually inapparent or subtle in contrast to granuloma annulare. Other findings include a sparse to moderately dense, primarily perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, plasma cells in the deep dermis in some biopsies (Fig. 14-13), involvement of the upper subcutis with thickened fibrous septa, and lipids which may be present in foamy histiocytes (105) or which may be inferred from the presence of cholesterol clefts (seen in <1% of cases) (106). Deep lymphoid follicles may be present in up to 10% of cases. Older lesions show telangiectases superficially. Blood vessels, particularly in the middle and lower dermis, often exhibit thickened walls. The thickened walls may be infiltrated with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)–positive, diastase-resistant material (42). Vascular changes of this type are seen particularly near foci containing thickened, hyalinized collagen bundles. Whereas the vascular changes often are conspicuous in lesions of the lower legs, they usually are mild or absent elsewhere (95). Histologic findings that are possibly correlated with the clinical presence of diabetes include florid palisading around degeneration of collagen (88) and cholesterol clefts (106).

Figure 14-11 Necrobiosis lipoidica. The presence of sclerosis can be identified by the relatively straight edges of the punch biopsy. The infiltrate involves the full thickness of the dermis and is arranged in a tier-like fashion.

Figure 14-12 Necrobiosis lipoidica. Histiocytes, lymphocytes, and degenerated collagen are present.

Figure 14-13 Necrobiosis lipoidica. Plasma cells at the dermal–subcutaneous junction are a typical finding.

Pathogenesis. The cause of necrobiosis lipoidica is unknown, and it is unclear whether the degeneration of collagen is a primary or a secondary event (91). Some authors have postulated that the degeneration of collagen is the result of vascular changes secondary to clinical or latent diabetes (107). However, evidence against a vascular cause includes the absence of vascular pathology in approximately one third of biopsies examined (88) and the fact that vessels that are affected are often situated in the lower dermis and are of a larger caliber than the vessels affected by diabetic microangiopathy. Abnormal glucose transport by fibroblasts has also been implicated (108).

Electron microscopic examination shows degenerative changes in collagen and elastin with loss of cross-striation in collagen fibrils. Collagen synthesis by fibroblasts is diminished (109).

Direct immunofluorescence studies have shown that necrobiotic foci contain fibrinogen. Deposits of immunoglobulin and C3 have been found in the vessel walls (110,111), but this is not a consistent finding (112).

Differential Diagnosis. See Table 14-1 for differentiation of necrobiosis lipoidica from granuloma annulare. Differentiation of necrobiosis lipoidica from annular elastolytic granuloma was discussed in the section on annular elastolytic granuloma. Occasionally, necrobiosis lipoidica shows discrete collections of epithelioid cells that may resemble those seen in sarcoidosis (92); however, significant alteration of the collagen is usually present in necrobiosis lipoidica and absent in sarcoidosis (92).

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinemia can simulate necrobiosis lipoidica but differs by showing a denser, more diffuse infiltrate with a greater number of foamy histiocytes, Touton giant cells, more extensive inflammation of the subcutis, and greater disruption of normal subcutaneous architecture. Lymphoid follicles and cholesterol clefts are more commonly seen in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma than in necrobiosis lipoidica (113).

Principles of Management. No treatment has been proven to be effective in large studies. Potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapy (114).

RHEUMATOID NODULES

Clinical Summary. Rheumatoid nodules are deeply seated firm masses that occur in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly over extensor prominences, such as the proximal ulna, the olecranon process, and the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints (115). They may occur elsewhere, such as the back of the hands, over amputation stumps (116), and, rarely, in extracutaneous sites, such as the lung and heart (117,118). The nodules vary in size from a few millimeters to 5 cm and may be solitary or numerous. Rarely, rheumatoid nodules show a central draining perforation (119). Rheumatoid factor is almost always found in high titer. Rarely, nodules may precede apparent joint disease (115). The rapid appearance of many small rheumatoid nodules has been reported in some patients treated with methotrexate and rarely with other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. This presentation has been termed accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis (120,121). The term rheumatoid nodulosis has also been proposed for the clinical presentation of multiple nodules on the hands/elbows with intermittent arthralgias/arthritis but no evidence of systemic rheumatoid arthritis (122). Rheumatoid nodules also occur in occasional patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who do not exhibit rheumatoid arthritis (123–125).

Pseudorheumatoid nodule is a term that has been applied to nodules in the subcutis that mimic rheumatoid nodules histologically but that develop in the absence of joint pain, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus (13,20). These occur in children or adults. The subsequent development of rheumatoid arthritis occurs infrequently in adults and rarely, if ever, in children. Because some of these nodules occur in patients with other lesions that are typical of intradermal granuloma annulare (13), the nodules are now generally considered to represent a subcutaneous variant of granuloma annulare.

Histopathology. Rheumatoid nodules occur in the subcutis and deep dermis. They exhibit one or several areas of fibrinoid degeneration of collagen that stain homogeneously red (Fig. 14-14). Nuclear fragments and basophilic material are often present, but mucin is almost always minimal or absent (43). These foci of degenerative change are surrounded by histiocytes in a palisade. Foreign-body giant cells are present in approximately 50% of biopsies (43). In the surrounding stroma, there is a proliferation of blood vessels associated with fibrosis. A sparse infiltrate of other inflammatory cells is associated with the histiocytes and surrounding stroma. Lymphocytes and neutrophils are most common, but mast cells, plasma cells, and eosinophils may be present. Occasionally, lipid is seen (43). Vasculitis has been described (126) but is not usually encountered (43). In perforating rheumatoid nodules, the central fibrinoid material extends through the skin surface (119).

Figure 14-14 Rheumatoid nodule. A: A deeply seated, circumscribed nodule exhibits palisading around basophilic material. B: Fibrin is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded arrangement.

Pathogenesis. Factors that have been implicated in the formation of rheumatoid nodules include trauma, vasculitis, and a specific T-cell–mediated immune reaction (115,127).

Differential Diagnosis. The principal differential diagnosis is subcutaneous granuloma annulare, which was discussed in the section on granuloma annulare. A distinction should be made from epithelioid sarcoma, also covered in that section. Nonabsorbable sutures or other foreign material may produce periarticular palisaded granulomas like those of rheumatoid nodule (128,129); in such instances, there should be a history of previous surgery or trauma, and birefringent material may be visible under polarized light. Rheumatic fever produces nodules (rheumatic nodules), especially over the elbows, knees, scalp, knuckles, ankles, and spine (130), which were confused with rheumatoid nodules in the early part of the 20th century. Histologically, a rheumatic fever nodule is less likely to show central, homogeneous fibrinoid necrosis. A palisade of histiocytes is usually not as well developed, and fibrosis is minimal or absent (117,131). Rarely, an infectious process, such as cryptococcosis, can produce a deep, palisaded granuloma. It can be differentiated from rheumatoid nodule because the palisade surrounds primarily necrotic debris and organisms rather than fibrinoid material.

Principles of Management. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis may improve rheumatoid nodules. For particularly symptomatic rheumatoid nodules, intralesional corticosteroids or surgical excision can be effective.

PALISADED NEUTROPHILIC AND GRANULOMATOUS DERMATITIS

Clinical Summary. The classic clinical presentation is umbilicated papules and nodules on the elbows and extensor surfaces of the digits, often seen in a patient with an associated collagen-vascular disease (132) (Fig. 14-15). Lesions previously termed Churg–Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules (133,134), and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis (135–137) present in a similar fashion and may represent the same condition. Over time, small case reports and case series have expanded the clinical spectrum of PNGD from the classic lesion to include variants presenting with plaques, patches, and other atypical morphologies. There exists considerable overlap with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.

Figure 14-15 Palisaded, neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis. Umbilicated erythematous papules of the elbows.

Histopathology. There are three sometimes overlapping histologic patterns in this rare condition: (a) early lesions resembling leukocytoclastic vasculitis but with broader cuffs of fibrin around vessel walls and abundant dermal basophilic nuclear debris, (b) fully developed lesions with a granuloma annulare–like appearance but associated with prominent neutrophils and neutrophilic dust (Figs. 14-16 and 14-17), and (c) a fibrosing, necrobiosis lipoidica–like final stage, sometimes with a sparse, superficial, and deep perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (see Table 14-2) (137,139). These differing histologic patterns may represent a temporal evolution of disease from early, evolving lesions to late, fully developed lesions.

Differential Diagnosis of Palisaded Neutrophilic and Granulomatous Dermatitis

Palisaded Neutrophilic and Granulomatous Dermatitis | Differential Diagnosis |

Early lesion | Leukocytoclastic vasculitis Erythema elevatum diutinum |

Fully developed lesion | Granuloma annulare Eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss) Granulomatosis and polyangiitis (Wegener) Granulomatous drug reaction (138) Infectious process |

Final stage | Necrobiosis lipoidica |

Figure 14-16 Palisaded, neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis. This fully developed lesion exhibits palisades of histiocytes, associated with neutrophils, basophilic debris, mucin, and degenerated collagen.

Figure 14-17 Palisaded, neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis. Neutrophilic dust and intact neutrophils are present in the centers of the palisades, accompanied by degenerated collagen bundles, fibrin, and mucin.

Pathogenesis. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with a wide variety of conditions. Whereas most are connective tissue disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus erythematosus, others include lymphoproliferative disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, and infections, particularly bacterial endocarditis (137,140). This condition is believed to represent an unusual immune complex–mediated vasculitis. Immunoglobulin M and C3 have been identified in small-vessel walls. The changes seen in fully developed lesions are believed to be a response to the vasculitic changes accompanying ischemia and enzymatic degradation by neutrophils.

Differential Diagnosis. See Tables 14-1 and 14-2.

Principles of Management. PNGD usually occurs in the setting of a systemic disease, and therapy is generally targeted at the underlying disease. Treatment of localized lesions with topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be helpful. Antimalarials and dapsone have also been used successfully (141).

SARCOIDOSIS

Clinical Summary. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of undetermined cause. A distinction is made between the subacute, transient type of sarcoidosis and the chronic, persistent type.

In subacute transient sarcoidosis, erythema nodosum is associated with hilar adenopathy, fever, and, in some cases, migrating polyarthritis and acute iritis, termed Löfgren syndrome. The disease subsides in almost all patients within a few months without sequelae. Cutaneous manifestations other than erythema nodosum do not occur (142,143). Occasionally, there is enlargement of subcutaneous lymph nodes (143,144).

In systemic sarcoidosis, cutaneous lesions are encountered in approximately one-fourth of patients (35,145–148).

In the United States, this disorder is much more common, more severe, and more chronic in African Americans (149,150). It is rare in children (151–153). A rare genetic disorder, Blau syndrome, may present in childhood and mimic sarcoidosis. This autosomal dominant disorder, with mutations in the NOD2 gene, is marked by granulomatous inflammation of the skin, uveal tract, and joints, notably sparing the lungs (154,155).

The most common cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis are brown-red or purple papules and plaques (156) (Fig. 14-18). Sarcoidosis is one of the “great mimickers,” and almost every cutaneous morphologic lesion type is possible. When papules or plaques of sarcoidosis are situated on the nose, cheeks, and ears, the term lupus pernio is applied (157). This presentation has been associated with upper respiratory involvement and greater disease severity (156,158).

Figure 14-18 Sarcoid. Pink-brown papules in clusters on the neck.

Less common manifestations of sarcoidosis include annular, lichenoid, erythrodermic, ichthyosiform, atrophic, ulcerating, verrucous, angiolupoid, hypopigmented, alopecic, and morpheaform variants. Lichenoid sarcoidosis manifests with small, flat violaceous papules (159). In erythrodermic sarcoidosis, the erythroderma may be generalized (160) or may consist of extensive, sharply demarcated, brown-red, slightly scaling patches with little or no palpable infiltration (161). In ichthyosiform sarcoidosis, ichthyotic changes favor the lower extremities (162), but at times they also may be present elsewhere on the skin (163,164). Rarely, there are extensive atrophic lesions (165). They may undergo ulceration (166,167). Multiple ulcers have been described also in plaque-like lesions (168). Angiolupoid sarcoid is characterized by a prominent telangiectatic component (169). Lesions of hypopigmented sarcoid appear as macules with or without an associated papular or nodular component (170). Subcutaneous nodules of sarcoidosis are also rare. Originally described by Darier and Roussy (171), they may occur in association with other cutaneous lesions (161,172) or alone (173). Sarcoidosis has been described in AIDS patients (174), and a transient form of chronic sarcoidosis has been reported in patients with hepatitis C undergoing treatment with interferon alfa and ribavirin (175). Interferon alfa can induce localized and systemic granulomatous inflammation. Other drugs, particularly TNF inhibitors, have also been described to induce localized granulomas and widespread drug-induced sarcoidosis-like syndromes.

Systemic sarcoidosis occasionally coexists with granuloma annulare (35). Cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis may localize to areas of scarring, as in herpes zoster scars (176,177). Tattoos (178,179), exogenous ochronosis (180), or other exogenous materials in the skin (181) may serve as a nidus for cutaneous lesions in patients with sarcoidosis. Two studies demonstrated polarizable foreign material in approximately 20% of cutaneous sarcoidal lesions from patients with systemic sarcoidosis (182,183).

Histopathology. The lesions of erythema nodosum occurring in subacute, transient sarcoidosis have the same histologic appearance as “idiopathic” erythema nodosum (144).

Like lesions in other organs, the cutaneous lesions of chronic, persistent sarcoidosis are characterized by the presence of circumscribed collections of epithelioid histiocytes—so-called epithelioid cell tubercles—which show little or no necrosis (Figs. 14-19 and 14-20).

Figure 14-19 Sarcoid. There are well-circumscribed, nodular collections of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis. This example also shows subcutaneous involvement, which is less common than purely dermal involvement.

Figure 14-20 Sarcoid. Well-circumscribed, roundish collections of epithelioid histiocytes, some multinucleated, with few lymphocytes.

The papules, plaques, and lupus pernio–type lesions show variously sized aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes scattered irregularly through the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (184). In the erythrodermic form, the infiltrate shows small granulomas in the upper dermis intermingled with numerous lymphocytes (161,185) and, rarely, also giant cells (186). Typical sarcoidal granulomas are found in the ichthyosiform lesions (163), in ulcerated areas (168), and in atrophic lesions (187,188). Verrucous sarcoid exhibits prominent associated acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (189,190). Biopsies of hypopigmented sarcoid may reveal granulomas, which may have a perineural component or fail to reveal granulomas (191). In subcutaneous nodules, larger epithelioid cell tubercles lie in the subcutaneous fat (173).

In typical cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis, the well-demarcated islands of epithelioid cells contain few, if any, giant cells. Those that are present are usually of the Langhans type. A moderate number of giant cells can be found in old lesions. These giant cells may be large and irregular in shape. In a minority of cases, giant cells contain asteroid bodies or Schaumann bodies (192). Asteroid bodies (Fig. 14-21), which are more common, are star-shaped eosinophilic structures that, when stained with phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin, produce a center that is brown-red with radiating blue spikes (193). Schaumann bodies are round or oval, laminated, and calcified, especially at their periphery. They stain dark blue because of the presence of calcium. Neither of these two bodies is specific for sarcoidosis: They have been observed in a variety of other granulomas, including those of leprosy, tuberculosis, foreign-body reactions, and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (193).

Figure 14-21 Sarcoid. Three star-shaped, eosinophilic asteroid bodies are present, one at the arrow and two in the upper right.

Classically, sarcoid has been associated with only a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate, particularly at the margins of the epithelioid cell granulomas (Fig. 14-20). Because of the scarcity of lymphocytes, the granulomas have been referred to as “naked” tubercles. However, lymphocytic infiltrates in sarcoid may occasionally be dense, as in tuberculosis (Fig. 14-22) (194). Occasionally, small foci of fibrin or necrosis showing eosinophilic staining is found in the center of some of the granulomas (Fig. 14-23) (158,184). A reticulum stain of sarcoid reveals a network of reticulum fibers surrounding and permeating the epithelioid cell granulomas. If the granulomas of sarcoidosis involute, fibrosis extends from the periphery toward the center, with gradual disappearance of the epithelioid cells (184). Fibrosis, however, is minimal to absent in most examples of sarcoidosis, with the exception of the morpheaform variant, where it is prominent (195). Other features that may sometimes be seen include elastophagocytosis, increased dermal mucin, and lichenoid inflammation (196).

Figure 14-22 Sarcoid. A fairly dense lymphocytic infiltrate is associated with the epithelioid histiocytes, a less common finding than the usual “naked tubercles.”

Figure 14-23 Sarcoid. On the left is fibrinoid material within the granulomatous component.

Systemic Lesions. The lungs are the most commonly involved organ in the chronic, persistent type of sarcoidosis, and respiratory symptoms are present in approximately 50% of patients (143). The lesions may be either nodular or diffuse with extensive parenchymal fibrosis.

In about 25% of the patients, ocular manifestations occur, most commonly chronic iridocyclitis. Splenomegaly is present in about 17%. In approximately 12%, osseous granulomas are present, most commonly in the phalanges of the fingers and toes. Involved phalanges appear swollen and deformed, often sausage-shaped (197). The skull may show circumscribed lytic lesions (198). About 8% of the patients have involvement of large salivary glands, usually the parotid. In about 5%, one encounters paresis of a cranial nerve, most commonly of the facial nerve (143). Oral mucosal involvement occurs very rarely (199). Asymptomatic enlargement of the hilar lymph nodes is present in 70%, of peripheral lymph nodes in 30%, and of the liver in 20% of the patients (143,200).

Sarcoidosis, although usually a benign disease, is fatal in approximately 5% of patients (143,200). The most common cause of death from sarcoidosis is right ventricular failure resulting from massive pulmonary involvement. Pulmonary hemorrhage and superimposed tuberculosis are rare causes of death. Another potentially fatal complication is renal insufficiency resulting from hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria (201) or from sarcoidal glomerulonephritis (202). In very rare instances, death results from massive involvement of the myocardium (203) or liver (204). Hypopituitarism from involvement of either the pituitary gland or the hypothalamus is also a rare fatal complication (205).

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis in a patient with systemic disease is based on clinical presentation, biopsy findings, and exclusion of other granulomatous processes. If skin lesions are present, they are an obvious choice for biopsy. In the absence of skin lesions, a Kveim test was frequently used in the past. The Kveim test involves intradermal injection of antigen derived from heat-sterilized suspension of sarcoidal tissue, particularly spleen or lymph node. The site is sampled 6 weeks later, with a positive result being the formation of a sarcoid-like granuloma (206,207). The test has a sensitivity of about 80%, with false-positive reactions occurring in less than 2% of cases (208). However, Kveim antigen is neither widely available nor approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It is infrequently used (149). The most accepted alternative approach for confirming a presumptive diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis is fiberoptic bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy (209). Endobronchial biopsy has also been shown to be useful (210), as has asymptomatic gastrocnemius muscle biopsy (211). Less specific ancillary tests, such as serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels, can provide supportive data.

Pathogenesis. The cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, and the disease may not have the same pathogenesis in all individuals. Alterations in immunologic status have long been recognized, including hypergammaglobulinemia, impaired delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to cutaneous antigens (anergy), and a shift of helper T lymphocytes from peripheral blood to sites of disease activity (212). However, these immunologic phenomena may represent a response to an as-yet-unidentified antigen (213). Mycobacteria, especially cell wall-deficient forms, have been postulated to represent the antigen source (213–216). Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been implicated by some studies, whereas others have suggested atypical mycobacteria (216,217). Other infectious causes such as Propionobacterium acnes and Rickettsia (218) have also been suggested. Others suggest the granulomas are a response to an inorganic antigen or misfolded amyloid protein sheets.

Electron microscopic examination of epithelioid cells fails to show any evidence of bacterial fragments, unlike the macrophages seen in granulomas caused by mycobacteria, although the cells contain primary lysosomes, some autophagic vacuoles, and complex, laminated residual bodies (219). The giant cells form through the coalescence of epithelioid cells with partial fusion of their plasma membranes. Schaumann bodies likely arise from laminated residual bodies of lysosomes. Asteroid bodies consist of collagen showing the typical 64- to 70-nm periodicity. It seems likely that this collagen is trapped between epithelioid cells during the stage of giant-cell formation (219).

Differential Diagnosis. The histologic differentiation of sarcoidosis from lupus vulgaris may be very difficult, and it is occasionally impossible. There is no absolute histologic criterion by which the two diseases can be differentiated with certainty. However, as a rule, the infiltrate in sarcoidosis lies scattered throughout the dermis, whereas the infiltrate in lupus vulgaris is located close to the epidermis. Furthermore, sarcoidosis usually shows few lymphoid cells at the periphery of the granulomas, giving them the appearance of “naked” granulomas. By contrast, lupus vulgaris often shows a marked inflammatory reaction around and between the granulomas. The granulomas of sarcoidosis usually show much less central necrosis than the granulomas of lupus vulgaris (220); however, not all biopsies of tuberculosis show necrosis, and some biopsies of sarcoid do. The epidermis in sarcoidosis is usually normal or atrophic. In lupus vulgaris, in addition to atrophy, areas of ulceration, acanthosis, and pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia are not uncommon. The absence of identifiable mycobacteria with acid-fast stain cannot be used to exclude tuberculosis because the organisms in lupus vulgaris are scarce and may be difficult or impossible to find.

Foreign-body granulomas can also resemble sarcoidosis. Polariscopic examination in search of doubly refractile material, such as silica, should be performed on biopsies suspected of being sarcoidosis. The presence of foreign material does not exclude a concurrent diagnosis of sarcoidosis (192). The papular type of acne rosacea occasionally shows “naked” tubercles indistinguishable from those of sarcoidosis, but unlike sarcoid, they are usually perifollicular.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree