Tuberculosis and Infections with Atypical Mycobacteria: Introduction

Tuberculosis is still an important worldwide disease. There were an estimated 9.27 million incident cases globally of TB in 2007.1 This is an increase from 9.24 million cases in 2006, to 8.3 million cases in 2000 and 6.6 million cases in 1990. Most of the estimated number of cases in 2007 were in Asia (55%) and Africa (31%), with small proportions in the Eastern Mediterranean region (6%), the European region (5%) and the Americas (3%). The five countries that ranked first to fifth in terms of total numbers of cases in 2007 were India, China, Indonesia, Nigeria, and South Africa. Of the 9.27 million incident cases in 2007, an estimated 1.37 million (14%) were HIV positive; 79% of these HIV-positive cases were in the African region.

In 2008, a total of 12,898 incident tuberculosis (TB) cases were reported in the United States; the TB rate declined 3.8% from 2007 to 4.2 cases per 100,000 population, the lowest rate recorded since national reporting began in 1953. In 2008, the TB rate in foreign-born persons in the United States was 10 times higher than in US-born persons. TB rates among Hispanics and blacks were nearly eight times higher than among non-Hispanic whites, and rates among Asians were nearly 23 times higher than among non-Hispanic whites. To ensure that TB rates decline further in the United States, especially among foreign-born persons and minority populations, TB prevention and control capacity should be increased. Additional capacity should be used to (1) improve case management and contact investigations; (2) intensify outreach, testing, and treatment of high-risk and hard-to-reach populations; (3) enhance treatment and diagnostic tools; (4) increase scientific research to better understand TB transmission; and (5) continue collaboration with other nations to reduce TB globally.2

HIV-positive people are about 20 times more likely than HIV-negative people to develop TB in countries with a generalized HIV epidemic, and between 26 and 37 times more likely to develop TB in countries where HIV prevalence is lower.

The so-called atypical Mycobacteria (Mycobacteria other than Mycobacteria tuberculosis, or MOTT) cause skin disease more frequently than does M. tuberculosis. They exist in various reservoirs in the environment. Among these organisms are obligate and facultative pathogens as well as nonpathogens. In contrast to the obligate pathogens, the latter do not cause disease by person-to-person spread.

Classification of Mycobacteria

Runyon group | |

|---|---|

Slow-Growing Mycobacteria | |

| |

| I |

| I |

| I |

| II |

| II |

| II |

| III |

| III |

| III |

| III |

Nonpathogens | |

| II |

| III |

| III |

| III |

| (Others) | |

Fast-Growing Mycobacteria | |

| |

| IV |

| IV |

| IV |

| |

| IV |

| IV |

| IV |

|

![]() Mycobacteria are acid-fast, weakly Gram-positive, nonsporulating, nonmotile rods.3 The family Mycobacteriaceae in the order Actinomycetales consists of only one genus, Mycobacteria which includes the obligate human pathogen M. tuberculosis and the closely related Mycobacteria bovis, Mycobacteria africanum, and Mycobacteria microti, as well as Mycobacteria leprae and a number of facultative pathogenic and nonpathogenic species, the MOTT. In the first and still often used classification of MOTT (the Runyon classification), a slow-growing group and a fast-growing group are recognized. The slow-growing group is subdivided according to pigment-forming properties in culture: group I—photochromogens (pigment formation on exposure to light); group II—scotochromogens (pigment production without light exposure); and group III—nonchromogens. Group IV comprises the rapid growers.

Mycobacteria are acid-fast, weakly Gram-positive, nonsporulating, nonmotile rods.3 The family Mycobacteriaceae in the order Actinomycetales consists of only one genus, Mycobacteria which includes the obligate human pathogen M. tuberculosis and the closely related Mycobacteria bovis, Mycobacteria africanum, and Mycobacteria microti, as well as Mycobacteria leprae and a number of facultative pathogenic and nonpathogenic species, the MOTT. In the first and still often used classification of MOTT (the Runyon classification), a slow-growing group and a fast-growing group are recognized. The slow-growing group is subdivided according to pigment-forming properties in culture: group I—photochromogens (pigment formation on exposure to light); group II—scotochromogens (pigment production without light exposure); and group III—nonchromogens. Group IV comprises the rapid growers.

![]() Today, over 60 species are named, 41 of which were included in the Approved Lists of Bacterial Names in 1980. New species continue to be identified, and over 50 have been associated with human disease.3 Species may be cultivable or not (M. leprae, Mycobacteria genavense). The main distinction in the group of cultivable Mycobacteria, the one between the slow growers and the rapid growers, seems to have occurred early in the development of the genus.

Today, over 60 species are named, 41 of which were included in the Approved Lists of Bacterial Names in 1980. New species continue to be identified, and over 50 have been associated with human disease.3 Species may be cultivable or not (M. leprae, Mycobacteria genavense). The main distinction in the group of cultivable Mycobacteria, the one between the slow growers and the rapid growers, seems to have occurred early in the development of the genus.

![]() For clinical purposes, the organisms may be further subdivided into obligate and facultative pathogens and nonpathogens. A modern classification scheme of the genus is presented in eTable 184-0.1. M. leprae and M. genavense are not included because they are not available for biochemical testing. The listing is neither exhaustive nor definitive.

For clinical purposes, the organisms may be further subdivided into obligate and facultative pathogens and nonpathogens. A modern classification scheme of the genus is presented in eTable 184-0.1. M. leprae and M. genavense are not included because they are not available for biochemical testing. The listing is neither exhaustive nor definitive.

Mycobacteria and the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Pandemic

The pandemic of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), with its profound and progressive suppression of cellular immune functions, has led to a resurgence of tuberculosis and the appearance or recognition of new mycobacterial pathogens. The Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI) complex is the most common cause of disseminated bacterial infections in patients with AIDS in the United States, but is much less frequently so in Europe. In AIDS patients, Mycobacterium kansasii is more common than M. tuberculosis. The incidence of tuberculosis in patients with AIDS is almost 500 times than that in the general population. Cutaneous disease in AIDS patients is frequently caused by MOTT.

Tuberculosis of the Skin

|

Tuberculosis of the skin has a worldwide distribution. Once more prevalent in regions with a cold and humid climate, it now occurs mostly in the tropics. Cutaneous TB incidence parallels that of pulmonary TB and developing countries still account for the majority of cases in the world. The emergence of resistant strains and the AIDS epidemic have led to an increase in all forms of TB (Table 184-1).

Host Immune Status | Clinical Disease | |

|---|---|---|

Exogenous infection | Naive Immune | Primary inoculation tuberculosis Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis |

Endogenous spread | High Low | Lupus vulgaris Scrofuloderma Acute miliary tuberculosis Orificial tuberculosis Metastatic tuberculous abscess (tuberculous gumma) |

Tuberculosis due to Bacille Calmette-Guérin | Naive | Normal primary complex-like reaction Perforating regional adenitis Postvaccination lupus vulgaris |

Tuberculids | Not clear | Tuberculids: Lichen scrofulosorum Papulonecrotic tuberculid Facultative tuberculids: Nodular vasculitis Erythema nodosum |

The two most frequent forms of skin tuberculosis are lupus vulgaris (LV) and scrofuloderma (Fig. 184-1). In the tropics, LV is rare, whereas scrofuloderma and verrucous lesions predominate. LV is more than twice as common in women than in men, whereas tuberculosis verrucosa cutis is more often found in men. Generalized miliary tuberculosis is seen in infants (and adults with severe immunosuppression or AIDS), as is primary inoculation tuberculosis. Scrofuloderma usually occurs in adolescents and the elderly, whereas LV may affect all age groups.

Mycobacteria multiply intracellularly, and are initially found in large numbers in the tissue.

M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and, under certain conditions, the attenuated BCG organism cause all forms of skin tuberculosis.

In LV, the bacteria often have virulence as low as that of the BCG. Large number of bacteria can be found in the lesions of a primary chancre or of acute miliary tuberculosis; in the other forms, their number in the lesions is so small that it may be difficult to find them.

M. tuberculosis may become dormant in the host tissue.

The human species is quite susceptible to infection by M. tuberculosis, with big differences among populations and individuals. Populations that have been in long-standing contact with tuberculosis are, in general, less susceptible than those who have come into contact with Mycobacteria more recently, presumably reflecting widespread immunity from subclinical infection. Age, state of health, environmental factors, and particularly the immune system are of importance. In Africans, tuberculosis frequently takes an unfavorable course, and tuberculin sensitivity may be more pronounced than in whites.

An extract of M. tuberculosis (tuberculin) was shown to produce a different skin reaction in sensitized individuals than in naive individuals, and this difference became the basis of a widely used diagnostic test. This reaction is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, induced by Mycobacteria during primary infection. This “old tuberculin” has now been replaced by purified protein derivative (PPD). More recently, purified species-specific antigens have been developed.6

Local intradermal injection (the method most widely used) leads to the local tuberculin reaction, which usually reaches its maximum intensity after 48 hours. It consists of a sharply circumscribed area of erythema and induration, and in highly hypersensitive recipients or after large doses, a pallid central necrosis may appear.

In an attempt to quantify the tuberculin reaction, an assay known as the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold test was developed to measure specific antigen-driven interferon-γ synthesis by whole blood cells and was approved by the FDA in 2005.

Tuberculin sensitivity usually develops 2–10 weeks after infection and persists throughout life. The state of sensitivity of an individual infected with M. tuberculosis is of considerable significance in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis skin lesions.

In patients with clinical tuberculosis, an increase in skin sensitivity usually indicates a favorable prognosis, and in tuberculous skin disease accompanied by high levels of skin sensitivity, the number of bacteria within the lesions is small. Tuberculin sensitivity (skin reactivity) is not necessary for immunity, however, and sensitivity and immunity do not always parallel each other.

Cutaneous inoculation leads to a tuberculous chancre or to tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (Fig. 184-2), depending on the immunologic state of the host.

Spread of Mycobacteria may occur by continuous extension of a tuberculous process in the skin (scrofuloderma) by way of the lymphatics (LV), or by hematogenous dissemination (acute miliary tuberculosis of the skin or LV).

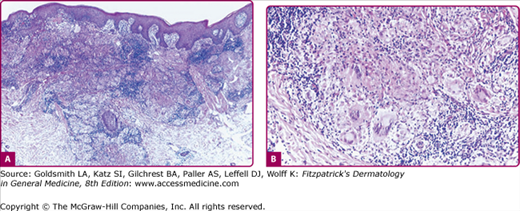

The hallmark of tuberculosis and infections with some of the slow-growing atypical Mycobacteria is the tubercle: an accumulation of epithelioid histocytes with Langhans-type giant cells among them and a varying amount of caseation necrosis in the center, surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes and monocytes. Although this tuberculoid granuloma is highly characteristic of several forms of tuberculosis, it may be mimicked by deep fungal infections, syphilis, and leprosy, as well as other diseases. As in leprosy, the histopathologic features of skin tuberculosis may be reflective of the host’s immune status.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedure has been used increasingly to ascertain the presence of mycobacterial DNA in skin specimens.7 Although the detection of specific DNA in tissues has yielded valuable information and will conceivably gain importance in the future, interpretation of the results of these tests in individual patients is still problematic.8 In one study, samples from 16 of 20 patients with sarcoidosis contained mycobacterial DNA, both tuberculous and nontuberculous.9 In another study of patients with confirmed or highly probable cutaneous tuberculosis or with erythema induratum, believed to indicate a host response to the infection, PCR testing showed 100% sensitivity and specificity in multibacillary disease. In paucibacillary disease, PCR testing showed 55% sensitivity and specificity, and only 80% of PCR-positive patients responded to antituberculosis therapy.7

In 2005, the FDA approved QFT-G as an in vitro diagnostic aid. In this test, blood samples are mixed with antigens and controls. For QFT-G, the antigens include mixtures of synthetic peptides representing two M. tuberculosis proteins: (1) ESAT-6 and (2) CFP-10. After incubation of the blood with antigens for 16–24 hours, the amount of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is measured.

If the patient is infected with M. tuberculosis, their white blood cells will release IFN-γ in response to contact with the TB antigens. The QFT-G results are based on the amount of IFN-γ that is released in response to the antigens.

Although more sensitive than the tuberculin skin test, the QFT-G may be negative in patients with early active tuberculosis and indeterminate results are more common in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Another similar assay, the T-SPOT®.TB test, measures the number of IFN-γ-producing T cells and is currently available in Europe. QFT-G testing is indicated for diagnosing infection with M. tuberculosis, including both TB disease and latent TB infection. Whenever M. tuberculosis infection or disease is being diagnosed by any method, the optimal approach includes coordination with the local or regional public health TB control programs.

Skin Diseases Caused by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis/Bovis Infection

Infection with M. tuberculosis used to be thought to result in characteristic clinical features.10 However, with increasing number of cases in immunocompromised individuals and improved diagnostic tools, many uncharacteristic manifestations have been discovered.

Tuberculous chancre and affected regional lymph nodes constitute the tuberculous primary complex in the skin. The condition is believed rare, but its incidence may be underestimated. In some regions with a high prevalence of tuberculosis and poor living conditions, primary inoculation tuberculosis of the skin is not unusual. Children are most often affected.

Tubercle bacilli are introduced into the tissue at the site of minor wounds. Oral lesions may be caused by bovine bacilli in nonpasteurized milk and occur after mucosal trauma or tooth extraction. Primary inoculation tuberculosis is initially multibacillary, but becomes paucibacillary as immunity develops.

The chancre initially appears 2–4 weeks after inoculation and presents as a small papule, crust, or erosion with little tendency to heal. Sites of predilection are the face, including the conjunctivae and oral cavity, as well as the hands and lower extremities. A painless ulcer develops, which may be quite insignificant or may enlarge to a diameter of more than 5 cm (Fig. 184-3). It is shallow with a granular or hemorrhagic base studded with miliary abscesses or covered by necrotic tissue. The ragged edges are undermined and of a reddish-blue hue. As the lesions grow older, they become more indurated, with thick adherent crusts.

Wounds inoculated with tubercle bacilli may heal temporarily but break down later, giving rise to granulating ulcers. Mucosal infections result in painless ulcers or fungating granulomas. Inoculation tuberculosis of the finger may present as a painless paronychia. Inoculation of puncture wounds may result in subcutaneous abscesses.

Slowly progressive, regional lymphadenopathy develops 3–8 weeks after the infection (Fig. 184-3) and may rarely be the only clinical finding. After weeks or months, cold abscesses may develop that perforate to the surface of the skin and form sinuses. The lymph nodes draining the primary glands may also be involved. Body temperature may be slightly elevated. The disease may take a more acute course, and in half of the patients, fever, pain, and swelling simulate a pyogenic infection. Early, there is an acute nonspecific inflammatory reaction in both skin and lymph nodes, and Mycobacteria are easily detected by Fite stain. After 3–6 weeks, the infiltrate and the regional lymph nodes acquire a tuberculoid appearance and caseation may occur.

Any ulcer with little or no tendency to heal and unilateral regional lymphadenopathy in a child should arouse suspicion. Acid-fast organisms are found in the primary ulcer and draining nodes in the initial stages of the disease. The diagnosis is confirmed by bacterial culture. The PPD reaction is negative initially and later converts to positive (Fig. 184-3).

The differential diagnosis encompasses all disease with a primary complex (Box 184-1).

If untreated, the condition may last up to 12 months. Rarely, LV develops at the site of a healed tuberculous chancre. The regional lymph nodes usually calcify.

The primary tuberculous complex usually produces immunity, but reactivation of the disease may occur. Hematogenous spread may give rise to tuberculosis of other organs, particularly of the bones and joints. It may also lead to acute miliary disease with a fatal outcome. Erythema nodosum occurs in approximately 10% of cases.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis is a paucibacillary disorder caused by exogenous reinfection (inoculation) in previously sensitized individuals with high immunity.

Inoculation occurs at sites of minor wounds or, rarely, from the patient’s own sputum. Members of professional groups handling infectious material are at risk. Children may become infected playing on contaminated ground.

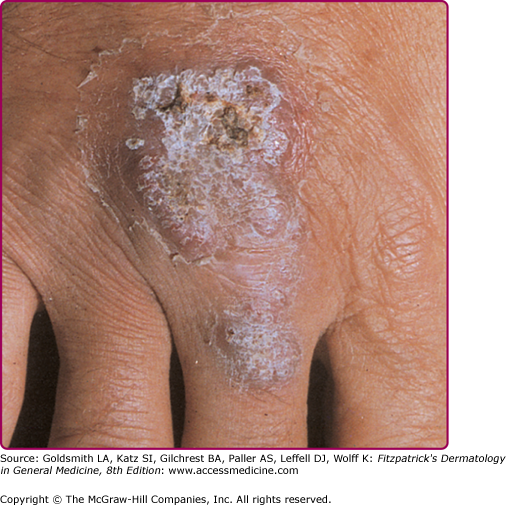

Lesions usually occur on the hands or, in children, on the lower extremities as a small asymptomatic papule or papulopustule with a purple inflammatory halo. They become hyperkeratotic and are often mistaken for a common wart. Slow growth and peripheral expansion lead to the development of a verrucous plaque with an irregular border (Fig. 184-4). Fissures discharging pus extend into the underlying brownish-red to purplish infiltrated base. The lesion usually is solitary, but multiple lesions may occur. Regional lymph nodes are rarely affected.

Lesions progress slowly and, if untreated, persist for many years. Spontaneous involution eventually occurs, leaving an atrophic scar.

The most prominent histopathologic features are pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with marked hyperkeratosis, a dense inflammatory infiltrate, and abscesses in the superficial dermis or within the pseudoepitheliomatous rete pegs. Epithelioid cells and giant cells are found in the upper and middle dermis. Typical tubercles are uncommon, and the infiltrate may be nonspecific.

Most Likely

|

Consider

|

Always Rule Out

|

LV is an extremely chronic, progressive form of cutaneous tuberculosis occurring in individuals with moderate immunity and a high degree of tuberculin sensitivity. Once common, LV has declined steadily in incidence. It has always been less common in the United States than in Europe. Females appear to be affected two to three times as often as males; all age groups are affected equally.

LV is a postprimary, paucibacillary form of tuberculosis caused by hematogenous, lymphatic, or contiguous spread from elsewhere in the body. Spontaneous involution may occur, and new lesions may arise within old scars. Complete healing rarely occurs without therapy.

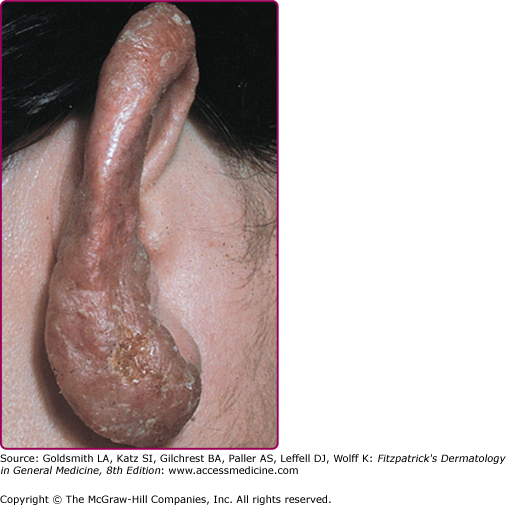

Lesions are usually solitary, but two or more sites may be involved simultaneously. In patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis, multiple foci may develop. In approximately 90% of patients, the head and neck are involved. LV usually starts on the nose, cheek, earlobe, or scalp and slowly extends onto adjacent regions. Other areas are rarely involved.

The initial lesion is a brownish-red, soft or friable macule or papule with a smooth or hyperkeratotic surface. On diascopy, the infiltrate exhibits a typical apple jelly color. Progression is characterized by elevation, a deeper brownish color (Fig. 184-5), and formation of a plaque (see Fig. 184-5). Involution in one area with expansion in another often results in a gyrate outline border. Ulceration may occur. Hypertrophic forms appear as a soft nodule (see eFig. 184-3.1) or plaque with a hyperkeratotic surface (eFig. 184-3.2). The mucosae may be primarily involved or become affected by the extension of skin lesions. Infection is manifest as small, soft, gray or pink papules, ulcers, or friable granulating masses.

After a transient impairment of immunity, particularly after measles (thus the term lupus postexanthematicus), multiple disseminated lesions may arise simultaneously in different regions of the body as a consequence of hematogenous spread from a latent tuberculous focus. During and after the eruption, a previously positive tuberculin reaction may become negative but will usually revert to positive as the general condition of the patient improves.

The most prominent histopathologic feature is the formation of typical tubercles. Secondary changes may be superimposed: epidermal thinning and atrophy or acanthosis with excessive hyperkeratosis or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Acid-fast bacilli are usually not found. Nonspecific inflammatory reactions may partially conceal the tuberculous structures. Old lesions are composed chiefly of epithelioid cells and may be impossible to distinguish from sarcoidal infiltrates (see eFig. 184-4.1).

Typical LV plaques may be recognized by the softness of the lesions, brownish-red color, and slow evolution. The apple jelly nodules revealed by diascopy are highly characteristic; finding them may be decisive, especially in ulcerated, crusted, or hyperkeratotic lesions. The result of the tuberculin test is strongly positive except during the early phases of postexanthematic lupus. Bacterial culture results may be negative, in which case the clinical diagnosis can usually be supported by positive PCR results for M. tuberculosis.

Involvement of the nasal or auricular cartilage may result in extensive destruction and disfigurement (Fig. 184-6). Atrophic scarring, with or without prior ulceration, is characteristic, as is recurrence within a scar. Fibrosis may be pronounced and mutilating.