Chapter 18

Tropical Dermatology

OVERVIEW

- The majority of tropical diseases are due to infections and infestations, a large proportion involving the skin.

- Hot humid conditions in the tropics and frequent lack of effective health care mean skin diseases are common and recurrent.

- Pyogenic bacteria commonly involve the skin, causing impetigo and erysipelas.

- The intensity and type of immune response to tropical diseases such as leprosy and leishmaniasis determine the clinical manifestations.

- Cutaneous fungal infections can be very florid, persistent and recurrent.

- In deep fungal infections, there is chronic inflammation in the subcutaneous tissues. These include chromoblastomycosis, mycetoma, blastomycosis and histoplasmosis.

- The most common infestations affecting the skin are scabies and lice. Others include tungiasis, myiasis, onchocerciasis, loiasis (Loa loa) and dracunculiasis.

Introduction

Tropical dermatology is a diverse topic covering a multitude of different skin diseases many of which are infections and infestations. This chapter concentrates on tropical diseases involving the skin (bacterial, viral, protozoan, helminth and arthropod related). Health workers in the tropics and subtropics may be familiar with many of the cutaneous presentations in the local population. However, due to the relative ease of world travel more visitors who are immunologically naïve may present locally with atypical features or florid disease. In addition, when these individuals return home they can present to their family medical practitioner who may be unfamiliar with tropical skin diseases.

Hot humid conditions in the tropics and subtropics provide an ideal environment for the proliferation of many organisms. Up to 50% of the local population is estimated to be affected by a skin disease in the tropics, the majority being infections or infestations such as impetigo, tinea and scabies. Many of these conditions are amenable to treatment. However, the hot humid conditions, overcrowding, poverty and the lack of resources mean that skin diseases are common and frequently recurrent. Local simple therapies can be very effective and may be administered by those with only minimal training. Health care infrastructure in the tropics is improving although many areas still suffer from lack of basic medicines and trained healthcare personnel.

Many tropical dermatoses have distinctive clinical features. Skin changes may result from the presence of the organisms, ova or larvae or a reaction in the skin to disease at a distant site.

Bacterial infections

Individuals living and travelling in the tropics are prone to Staphylococcus aureus infections on the skin in the form of impetigo (see Chapter 13). Bacterial infections may arise secondary to minor trauma or may be superimposed on any other skin disease. Clinical features include erythema, exudates, vesicles/bullae and crusting. Impetigo is highly contagious and many family members may be infected.

Deeper infections mainly caused by Streptococcus result in erysipelas or cellulitis, which may be accompanied by systemic symptoms. The face and limbs are most frequently affected. Deep infections may occur following minor trauma or impaired barrier function due to pre-existing skin diseases such as tinea, scabies, atopic or irritant dermatitis.

The skin changes are characterised by marked erythema and tissue swelling. The patient may have systemic symptoms such as fever, rigors and malaise. Individuals who do not have immediate access to antiseptics or antibiotics may develop severe skin changes and ultimately bacteraemia.

Leprosy

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, which results in a chronic granulomatous infection of the skin and peripheral nerves. Leprosy is endemic in Africa, south-east Asia, the Indian subcontinent and South America. Aerosols from the nasal mucosa are thought to be the mode of transmission between humans, but animal reservoirs do exist (nine-banded armadillo, chimpanzees and some monkeys). The incubation period is highly variable (6 months to 40 years) with a mean of 4–6 years.

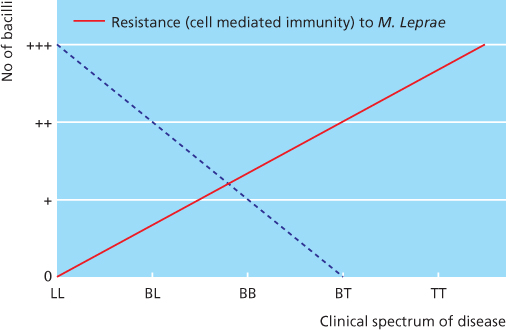

There is a spectrum of clinical disease (Figure 18.1) depending on the patient’s cell-mediated immunity to M. leprae. Patients whose immune systems respond poorly have clinical disease characterised by numerous skin lesions with numerous mycobacteria (multibacillary). Patients whose immune systems are responding well to the infection have very few mycobacteria present (paucibacillary) in isolated skin lesions. These two ends of the spectrum are referred to as tuberculoid leprosy (good immune response) and lepromatous leprosy (LL) (poor immune response). Clinical intermediates exist and these are termed borderline cases (Figures 18.2–18.5).

Figure 18.1 Spectrum of clinical disease in leprosy. BB, mid-borderline leprosy; BL, borderline lepromatous leprosy; BT, borderline tuberculoid leprosy; LL, lepromatous leprosy; TT, tuberculoid leprosy.

Figure 18.2 Tuberculoid leprosy: hypopigmented patches.

Figure 18.3 Tuberculoid leprosy.

Figure 18.4 Lepromatous leprosy.

Figure 18.5 Borderline leprosy.

Diagnosis

Typical clinical findings are as follows.

- In tuberculoid leprosy (TT) there is a single anaesthetic patch or plaque with a raised border.

- In LL, there are widespread symmetrical shiny papules, nodules and plaques which are not anaesthetic.

- In borderline leprosy (BT, BB, BL), there are varying numbers of lesions, few in BT and numerous in BL. They may be widespread but are asymmetrical. BB is mid-borderline leprosy.

- Palpably enlarged cutaneous nerves (great auricular nerve in the neck, the superficial branch of the radial nerve at the wrist, the ulnar nerve at the elbow, the lateral popliteal nerve at the knee and the sural nerve on the lower leg).

- Glove and stocking sensory loss leads to secondary changes through trauma such as blisters, erosions and ulcers (neuropathic) on anaesthetic fingers/toes.

- Deformity due to invasion of the peripheral nerves with leprosy bacilli, a leprosy reaction or recurrent trauma to anaesthetic limbs.

Slit skin smears measure the numbers of bacilli in the skin (bacterial index, BI—see Box 18.1) and the percentage of these that are living (morphological index, MI).

Box 18.1 Bacterial index (BI)

- 0 No bacilli seen

- 1+ 1–10 bacilli in 100 oil immersion fields

- 2+ 1–10 bacilli in 10 oil immersion fields

- 3+ 1–10 bacilli in 1 oil immersion field

- 4+ 10–100 bacilli in an average oil immersion field

- 5+ 100–1000 bacilli in an average oil immersion field

- 6+ >1000 bacilli in an average oil immersion field

Treatment

Paucibacillary leprosy (BI of 0 or 1+):

- rifampicin 600 mg once a month

- dapsone 100 mg daily

- for 6 months.

Multibacillary leprosy (BI of 2+ or more):

- rifampicin 600 mg once a month

- clofazimine 300 mg once a month

- clofazimine 50 mg/day

- dapsone 100 mg/day

- for 12 months.

An estimated 20–40% of patients with leprosy develop immunologically mediated reactions (most common in borderline leprosy cases) that can permanently damage nerve function. These so called ‘reversal reactions’ can be type 1 (T1R delayed hypersensitivity) or type 2 (T2R immune complex mediated). Type 1 reactions are characterised by marked inflammation and oedema in skin lesions, acral oedema and acute neuritis manifested by nerve pain/sudden onset of loss of sensation/function. Urgent treatment with 40–60 mg oral prednisolone daily should be given and then tapering doses over 3–6 months, in addition to the anti-lepromatous therapy. Type 2 reactions resemble erythema nodosum but are generally more widespread and the erythematous nodules may be superficial as well as deep, and may ulcerate. Neuritis may accompany the erythema nodosum leprosum, systemic upset (fever, malaise), photophobia and iritis and so on. Patients should be treated promptly with aspirin and oral prednisolone.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis affects approximately 12 million people worldwide and is found in over 80 countries (in the ‘Old World’ in Africa, Asia and Europe and in the ‘New World’ in Central and South America). Leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania protozoan parasites transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly (usually at night). Rarely in humans transmission via blood transfusion, congenital passage and sexual intercourse have been reported. Animal reservoirs include dogs, rodents, foxes and jackals. Clinically, leishmaniasis is classified into cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral, depending on the parasite’s ability to proliferate at a particular temperature. Therefore, the amastigote parasites may remain in the skin or be carried by macrophages to internal organs. There are many different species of Leishmania parasites, each restricted to a particular geographical region (Box 18.2).

Box 18.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis

New World (Americas)

Leishmania tropica mexicana, Leishmania amazonensis, Leishmania brasiliensis (cutaneous + mucocutaneous)

Old World

L. tropica, Leishmania major, Leishmania aethiopica (mucocutaneous), Leishmania infantum (cutaneous + visceral)

Cutaneous lesions usually on exposed skin sites develop within weeks of the sandfly bite. Children are more frequently affected than adults. Several family members may be affected simultaneously, often bitten by the same sandfly. Painless erythematous papules leading to nodules and eventually ulceration can classically be seen. The clinical presentation varies according to the host’s nutritional state, their immunity and the Leishmania species involved. Spontaneous resolution may occur after 2–10 months, but latent reactivation after several years in an area of minor skin trauma means leishmaniasis can be an unpredictable disease.

Mucosal involvement may occur in isolation or concurrently with cutaneous lesions, and in some cases there may be a delay of up to 20 years between the appearance of cutaneous and mucosal lesions. Mucosal lesions may be painful and can lead to nasal obstruction, congestion, tissue destruction and bleeding.

Acute leishmaniasis

A red nodule similar to a boil (‘Delhi boil’, ‘Balkan sore’) occurs at the site of the bite. The nodules enlarge and may ulcerate (moist and exudative or dry and crusted) (Figure 18.6). Lesions usually heal spontaneously after approximately 1 year, leaving a pale cribriform scar.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree