Chapter 6. Treatment Planning: Facial Aesthetics

THE INTERVIEW

The preoperative, and often repeat, consultation is critical to the success of rhinoplasty surgery. Numerous important points need to be addressed by the surgeon in consultation. A patient’s motivation for surgery is of utmost importance. What is the reason the patient is interested in surgery? Is the patient undergoing the procedure for self image or in response to external pressures? It is important that the patient is internally motivated to undergo rhinoplasty surgery, with its inherent risks and complications, and is not feeling pressure from another person. It is also important that the patient is not doing it to regain a lost romance or be rehired to a lost job.

The preoperative, and often repeat, consultation is critical to the success of rhinoplasty surgery. Numerous important points need to be addressed by the surgeon in consultation. A patient’s motivation for surgery is of utmost importance. What is the reason the patient is interested in surgery? Is the patient undergoing the procedure for self image or in response to external pressures? It is important that the patient is internally motivated to undergo rhinoplasty surgery, with its inherent risks and complications, and is not feeling pressure from another person. It is also important that the patient is not doing it to regain a lost romance or be rehired to a lost job.

Historically, authors and artists have depicted the “normal” face in various ways. With regards to the nose, its structure has been described in both absolute and relative lengths, widths, and angles. In reality, there is no true normal nose but values and relationships exist that are considered normal for most persons. Rather than subjecting each prospective patient to a plethora of measurements, the surgeon should be familiar with the important ones and decide which are most useful. After facial analysis, any deviations from normal should be discussed with the patient to discuss the patient’s level of motivation for treatment. In almost all cases, the patient’s desires should take precedence over the surgeon’s effort to meet established “norms” in rhinoplasty surgery. Rhinoplasty requires an aesthetic eye as well as a sharp pencil.1

Historically, authors and artists have depicted the “normal” face in various ways. With regards to the nose, its structure has been described in both absolute and relative lengths, widths, and angles. In reality, there is no true normal nose but values and relationships exist that are considered normal for most persons. Rather than subjecting each prospective patient to a plethora of measurements, the surgeon should be familiar with the important ones and decide which are most useful. After facial analysis, any deviations from normal should be discussed with the patient to discuss the patient’s level of motivation for treatment. In almost all cases, the patient’s desires should take precedence over the surgeon’s effort to meet established “norms” in rhinoplasty surgery. Rhinoplasty requires an aesthetic eye as well as a sharp pencil.1

The surgeon should identify functional problems as well aesthetic concerns and prioritize these in a problem list. It is important to educate the patient about any factors that may make a result fall short of the planned goals and set realistic expectations for surgery.

The surgeon should identify functional problems as well aesthetic concerns and prioritize these in a problem list. It is important to educate the patient about any factors that may make a result fall short of the planned goals and set realistic expectations for surgery.

It is important to question the patient about any functional problems when planning the operative steps.

It is important to question the patient about any functional problems when planning the operative steps.

Is there a history of difficulty breathing?

Is there a history of difficulty breathing?

If so, is this seasonal or sporadic?

If so, is this seasonal or sporadic?

What medications does the patient take and how frequently?

What medications does the patient take and how frequently?

Several maneuvers performed in rhinoplasty can actually lead to airway obstruction. In these cases, counteractive procedures need to be incorporated into the treatment plan and the patient needs to be counseled about the possibility of new or persistent airway obstruction. In situations where aesthetic goals (ie, narrowing of the nose) may be limited due to functional concerns, it is preferable to err on the side of function rather than create airway problems while attempting to achieve aesthetic goals.

Several maneuvers performed in rhinoplasty can actually lead to airway obstruction. In these cases, counteractive procedures need to be incorporated into the treatment plan and the patient needs to be counseled about the possibility of new or persistent airway obstruction. In situations where aesthetic goals (ie, narrowing of the nose) may be limited due to functional concerns, it is preferable to err on the side of function rather than create airway problems while attempting to achieve aesthetic goals.

In order to successfully meet the patient’s goals, it is important that the patient clearly communicate the desired changes that are to be achieved. Occasionally, a patient will offer a broad concern such as “I just don’t like my nose.” In this case, the surgeon may be able to identify aspects of the nose that deviate from the aesthetic norm. When these features are tactfully presented to the patient, there is frequently immediate agreement and a clarification of treatment objectives. The surgeon should feel that he is not leading the patient. To some extent, the result depends on the anatomy and physiology with which the patient presents. It is important that the patient realizes the limitations to what can be achieved in given individuals.

In order to successfully meet the patient’s goals, it is important that the patient clearly communicate the desired changes that are to be achieved. Occasionally, a patient will offer a broad concern such as “I just don’t like my nose.” In this case, the surgeon may be able to identify aspects of the nose that deviate from the aesthetic norm. When these features are tactfully presented to the patient, there is frequently immediate agreement and a clarification of treatment objectives. The surgeon should feel that he is not leading the patient. To some extent, the result depends on the anatomy and physiology with which the patient presents. It is important that the patient realizes the limitations to what can be achieved in given individuals.

Similarly, the surgeon must be able to identify the areas of concern. One of the most crucial aspects of the rhinoplasty consultation is to make certain that the surgeon understands the patient’s goals and that these goals are realistic. Computer imaging is a useful tool to help determine patient goals and will be discussed in this chapter. The surgeon must also honestly assess his ability to achieve the result. It is wise to be conservative in rhinoplasty surgery at the beginning of one’s career. This may mean referring a difficult case to a more experienced surgeon or staying within one’s comfort zone to avoid doing irreparable harm. It is better to return for a minor revision than create the need for a major revision.

Similarly, the surgeon must be able to identify the areas of concern. One of the most crucial aspects of the rhinoplasty consultation is to make certain that the surgeon understands the patient’s goals and that these goals are realistic. Computer imaging is a useful tool to help determine patient goals and will be discussed in this chapter. The surgeon must also honestly assess his ability to achieve the result. It is wise to be conservative in rhinoplasty surgery at the beginning of one’s career. This may mean referring a difficult case to a more experienced surgeon or staying within one’s comfort zone to avoid doing irreparable harm. It is better to return for a minor revision than create the need for a major revision.

THE EXAMINATION

The six standard preoperative rhinoplasty views are frontal (Figure 6-1), oblique (Figures 6-2 and 6-4), and lateral (Figures 6-3 and 6-5) as well as worm’s eye (Figure 6-6).

The six standard preoperative rhinoplasty views are frontal (Figure 6-1), oblique (Figures 6-2 and 6-4), and lateral (Figures 6-3 and 6-5) as well as worm’s eye (Figure 6-6).

Figure 6-1

Figure 6-2

Figure 6-3

Figure 6-4

Figure 6-5

Figure 6-6

Frontal view: From the patient’s frontal view, several important landmarks and relationships should be identified.

Frontal view: From the patient’s frontal view, several important landmarks and relationships should be identified.

Facial dimensions: The face may be divided into various parts as a means of evaluating areas of imbalance. Vertically, the distance from a horizontal line across the hairline to a line across the eyebrows defines the upper third of the face. The middle facial third is the distance from a line between the eyebrows to the subnasale and the lower facial third from the subnasale to the bottom of the chin. Although these have traditionally been defined as facial thirds, the lower third is slighter larger than the middle third, and the middle third is slightly longer than the upper third.2,3 Horizontally, equal fifths can be created by lines running vertically through the lateral and medial canthi of each eye.

Facial dimensions: The face may be divided into various parts as a means of evaluating areas of imbalance. Vertically, the distance from a horizontal line across the hairline to a line across the eyebrows defines the upper third of the face. The middle facial third is the distance from a line between the eyebrows to the subnasale and the lower facial third from the subnasale to the bottom of the chin. Although these have traditionally been defined as facial thirds, the lower third is slighter larger than the middle third, and the middle third is slightly longer than the upper third.2,3 Horizontally, equal fifths can be created by lines running vertically through the lateral and medial canthi of each eye.

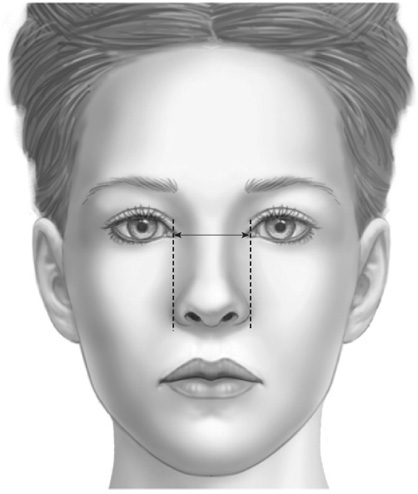

Alar width: The width of the nose at the alar base should approximate the span between the medial canthi (Figure 6-7). Wide alar bases may require skin and/or soft tissue excision.

Alar width: The width of the nose at the alar base should approximate the span between the medial canthi (Figure 6-7). Wide alar bases may require skin and/or soft tissue excision.

Figure 6-7. Alar width as it approximates the distance between the medial canthi.

Nasal width: The width of the nose at the level of the nasal bones as well as the alar base should be evaluated. In general, the width of the nasal bones at their base should be four-fifths of the width of the alar base. Wide nasal bones may require osteotomy and infracture.

Nasal width: The width of the nose at the level of the nasal bones as well as the alar base should be evaluated. In general, the width of the nasal bones at their base should be four-fifths of the width of the alar base. Wide nasal bones may require osteotomy and infracture.

Dorsal aesthetic lines: As important as any component of the nasal evaluation, the surgeon must note the appearance of the dorsal aesthetic lines (Figure 6-8). By definition, they originate on the supraorbital ridges near the medial end of the eyebrow and begin to converge along the glabellar area. They are narrowest at the level of the medial canthal ligaments and then diverge gradually to end at the tip-defining points.

Dorsal aesthetic lines: As important as any component of the nasal evaluation, the surgeon must note the appearance of the dorsal aesthetic lines (Figure 6-8). By definition, they originate on the supraorbital ridges near the medial end of the eyebrow and begin to converge along the glabellar area. They are narrowest at the level of the medial canthal ligaments and then diverge gradually to end at the tip-defining points.

Figure 6-8. Dorsal aesthetic lines.

Nasal tip: The appearance of the tip should be evaluated in isolation and as it relates to the nasal dorsum. The tip-defining points are an important landmark in tip analysis and occur at the transition point between the medial and lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages. In photographs, the tip-defining points are identified as two bright spots that reflect an external light source. Tip projection, position and the distance between the highlights, the angle of divergence between the crura, and the length of the middle and lateral crura should also be evaluated. The thickness of the nasal skin and the strength of each section of alar cartilage are assessed by visualization and palpation. Tip projection and rotation are best evaluated on the lateral view. The nasal tip is perhaps the most defining feature of a nose. In one random series, the tip-defining points were 8.9 +/– 1.6 mm separate from each other.4 The course of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages should be noted. In some patients, the lateral crura diverge from the rim at an angle greater than the normal 30 to 45 degrees. This anatomic variation produces a round tip often described as a “parentheses” deformity on frontal view.5 Aside from the aesthetic implications, the malposition of the lateral crura places them at risk for injury when making a standard intracartilaginous incision.6 The “boxy tip” is due to an increased angle of divergence between the genu of the lower lateral cartilages (more than 30 degrees), a widened domal arc (more than 4 mm), or a combination of the two.7

Nasal tip: The appearance of the tip should be evaluated in isolation and as it relates to the nasal dorsum. The tip-defining points are an important landmark in tip analysis and occur at the transition point between the medial and lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages. In photographs, the tip-defining points are identified as two bright spots that reflect an external light source. Tip projection, position and the distance between the highlights, the angle of divergence between the crura, and the length of the middle and lateral crura should also be evaluated. The thickness of the nasal skin and the strength of each section of alar cartilage are assessed by visualization and palpation. Tip projection and rotation are best evaluated on the lateral view. The nasal tip is perhaps the most defining feature of a nose. In one random series, the tip-defining points were 8.9 +/– 1.6 mm separate from each other.4 The course of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages should be noted. In some patients, the lateral crura diverge from the rim at an angle greater than the normal 30 to 45 degrees. This anatomic variation produces a round tip often described as a “parentheses” deformity on frontal view.5 Aside from the aesthetic implications, the malposition of the lateral crura places them at risk for injury when making a standard intracartilaginous incision.6 The “boxy tip” is due to an increased angle of divergence between the genu of the lower lateral cartilages (more than 30 degrees), a widened domal arc (more than 4 mm), or a combination of the two.7

Hyperactivity of the depressor septi nasi muscle has been noted to contribute to drooping of the nasal tip. This may be diagnosed preoperatively by observing the patient at rest and then when smiling. Muscle contraction will worsen the deformity and provide an indication to address this paired muscle at surgery.8

Hyperactivity of the depressor septi nasi muscle has been noted to contribute to drooping of the nasal tip. This may be diagnosed preoperatively by observing the patient at rest and then when smiling. Muscle contraction will worsen the deformity and provide an indication to address this paired muscle at surgery.8

Nasal deviation

Nasal deviation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Numerous findings on a patient’s physical exam may pose limitations to the expected outcome irrespective of the skill of the surgeon. Despite the artistry with which the supportive bone and cartilage are manipulated, the ultimate aesthetic outcome of the nose is based on how the overlying skin drapes over the supporting framework. Thick and thin skin can both predispose to suboptimal outcomes. Thick skin draped over even the most well-crafted bone and cartilage will hide the detail in these supporting structures. In contrast, thin skin is unforgiving in that all imperfections can be visible. Suture knots, as well as minor irregularities, can become alarmingly apparent requiring revision surgery.

Numerous findings on a patient’s physical exam may pose limitations to the expected outcome irrespective of the skill of the surgeon. Despite the artistry with which the supportive bone and cartilage are manipulated, the ultimate aesthetic outcome of the nose is based on how the overlying skin drapes over the supporting framework. Thick and thin skin can both predispose to suboptimal outcomes. Thick skin draped over even the most well-crafted bone and cartilage will hide the detail in these supporting structures. In contrast, thin skin is unforgiving in that all imperfections can be visible. Suture knots, as well as minor irregularities, can become alarmingly apparent requiring revision surgery.