Chapter 62 Treatment of Meniscus Tears with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Introduction

The incidence of lateral meniscus tears has been reported to be higher than the incidence of medial meniscus tears with acute ACL injuries.1 Shelbourne and Gray2 found that of 448 patients with acute ACL injuries, 62% had lateral meniscus tears and 42% had medial meniscus tears, whereas in 609 patients with chronic ACL deficiency, 49% had lateral meniscus tears and 60% had medial meniscus tears. Cipolla et al3 found that of 218 acute injuries, 59% had lateral meniscus tears and 28.5% had medial meniscus tears, whereas in 552 chronic ACL injuries, 41.6% had lateral meniscus tears and 74% had medial meniscus tears. The lateral meniscus is mobile and translates 9 to 11 mm in the anteroposterior plane, whereas the medial meniscus translates only 2 to 5 mm.4 The lateral meniscus is more frequently injured acutely because of its extreme mobility, and the peripheral and posterior portions of the meniscus are prone to getting caught in the joint during an ACL instability episode, which may explain the high incidence of posterior horn avulsion tears with acute ACL injuries. The less mobile medial meniscus is less injured with acute ACL injuries, and it may take consecutive giving-way episodes for the peripheral posterior third of the meniscus to become caught in the joint. When patients do have a medial meniscus tear with an acute ACL injury, it is typically a peripheral vertical tear in the posterior third of the meniscus. This tear can extend anteriorly with additional giving-way episodes and eventually become a bucket-handle tear.

Meniscus Tears to Leave in Situ

With acute ACL injuries, most meniscus tears are not symptomatic for the patient. The patient’s inability to fully extend the knee is usually due to the ACL stump being lodged in the intercondylar notch. Shelbourne et al5 found that joint line tenderness observed at the time of acute ACL injury does not correlate to the presence or absence of meniscus tears at the time of surgery. Over a 2-year period, 173 patients were seen for acute injury and were evaluated for joint line tenderness, and then the type of meniscus tear was recorded at the time of surgery. The investigators found that medial joint line tenderness was 45% sensitive and 34% specific for a medial meniscus tear. Lateral joint line tenderness was 58% sensitive and 49% specific for a lateral meniscus tear.5 We now delay ACL surgery until the patient’s knee has full range of motion and no swelling and the patient has good leg control. On the day of surgery, very few patients have joint line tenderness but about 50% have a meniscus tear.6 It appears that meniscus injuries in conjunction with acute ACL injuries are difficult to determine preoperatively based on joint line tenderness exam.

The meniscus has a blood supply provided by the perimeniscal capillary plexus, and these capillaries extend into 20% to 30% of the body of the medial meniscus and 10% to 25% of the lateral meniscus.7,8 Tears in the peripheral vascular zone of the meniscus are thought to be ideal for meniscus repair, but many can heal without specific repair treatment. The acuteness or chronicity of the ACL injury is not the deciding factor for determining the treatment of the meniscus. Rather, it is the location of the tear and the degenerative nature of the tear that help determine treatment.

Lateral Meniscus Tears

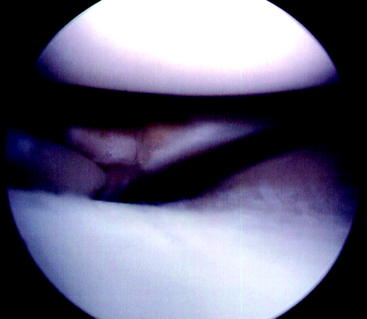

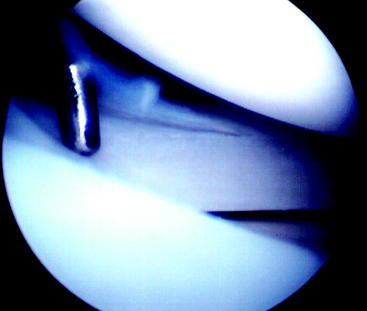

Complete removal of a torn lateral meniscus has a poor prognosis.9 In the early 1980s, the senior author observed the almost 100% success with repair of lateral meniscus tears and came to the conclusion that many of the lateral meniscus tears being repaired probably did not need repair. Therefore the senior author began to change his treatment of lateral meniscus tears from repairing 80% of the tears in 1984 to repairing 15% in 1992. During that same time, he changed his treatment from leaving lateral meniscus tears in situ in 4% of tears in 1984 to 70% in 1992. The types of lateral meniscus tears left alone included posterior horn avulsions (52 tears; Fig. 62-1), stable vertical tears that were posterior to the popliteus tendon (99 tears; Fig. 62-2), and nondisplaced vertical tears that extended anterior to the popliteus tendon (27 tears).10 With a follow-up at a mean of 2.6 years (range 1–9 years), Fitzgibbons and Shelbourne10 found that no patients returned to the clinic reporting symptoms of a lateral meniscus tear. One patient twisted his knee playing basketball at 114 days after ACL reconstruction and had a displaced bucket-handle medial meniscus tear. At the time of follow-up arthroscopy, the original vertical lateral meniscus tear had progressed to a complex T-type tear, but the tear did not extend anterior to the popliteus.

Shelbourne and Heinrich11 performed another long-term follow-up of 332 patients who had lateral meniscus tears left in situ or treated with abrasion and trephination without suture repair. The patients also had no medial meniscus tears or chondromalacia greater than grade II to isolate the factor of lateral meniscus tears in the long-term follow-up analysis. At a mean of 5.1 years after surgery, 162 patients (95%) had normal radiographs, six patients had nearly normal radiographs, and two patients had abnormal radiographs for lateral joint space narrowing using IKDC criteria. Of 70 patients with posterior horn avulsion tears left in situ, two (2.9%) underwent a subsequent procedure to remove the tear. Of 50 patients with radial flap tears, three patients (6%) needed a subsequent surgery for the tear. Of 169 patients with peripheral or posterior tears left in situ, three patients (1.8%) required subsequent surgery for the tear. None of the 43 patients who had peripheral or posterior tears treated with abrasion and trephination required further surgery.11

Medial Meniscus Tears

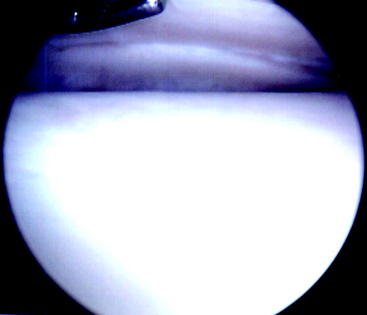

Medial meniscus tears seen at the time of acute ACL reconstruction are traumatic in nature and are usually in the vascular zone of the meniscus. A common type of tear seen with acute ACL injury is a peripheral or posterior stable medial meniscus tear, which can be easily missed (Fig. 62-3). This type of tear is not symptomatic for the patient, and it is possible that many of these tears heal on their own in patients who do not undergo an ACL reconstruction acutely or semi-acutely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree