CHAPTER 34 Treatment of blepharoplasty complications

History

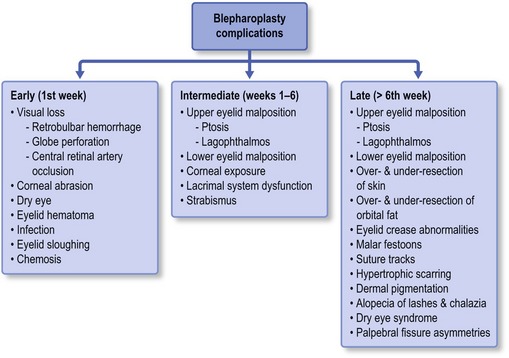

The following chapter presents intraoperative and postoperative complications from blepharoplasty based upon timeframe from surgery and offers guidance for treatment and/or prevention of each. It is important to realize that some complications may arise in multiple time periods postoperatively. Early recognition and appropriate treatment is essential; but the best therapeutic option often differs based upon the timing from surgery. An outline provides an overview of the most common and concerning complications allowing the reader to develop appropriate clinical perspective. This chapter breaks from the standard layout in the textbook in order to offer the clinician a more clinically useful reference for understanding and treating the postoperative blepharoplasty complication (Fig. 34.1).

Complications in the early postoperative period (1st week)

Visual loss

Retrobulbar hemorrhage

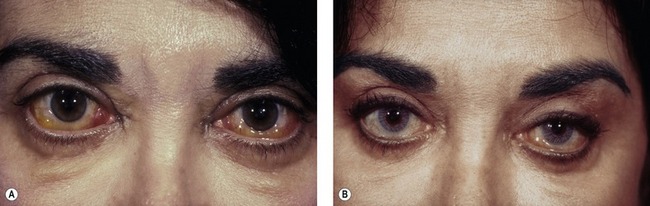

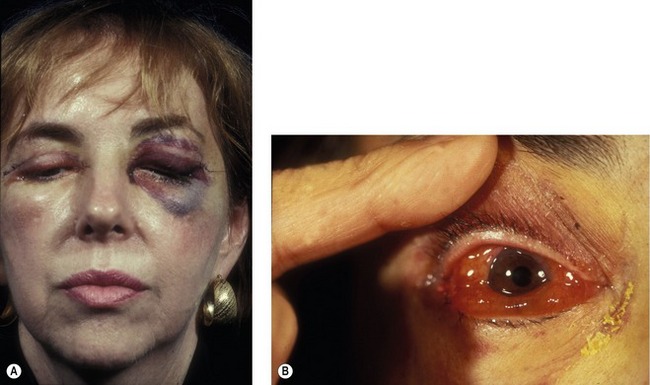

The incidence of retrobulbar hemorrhage was reported in the plastic surgery literature at 0.04%.1 More recently, an epidemiologic study of greater than 250 000 blepharoplasty cases performed by oculoplastic specialists found the incidence of retrobulbar hemorrhage to be 0.05%; associated permanent visual loss was diagnosed in 0.0045%.2 This corresponds to a 1/2000 risk of significant hemorrhage and a 1/10 000 risk of permanent visual loss. Most often clinical presentation is within the first 24 hours after surgery, although bleeding has been reported as late as 9 days after surgery.3 Patients may complain of pain, pressure, diplopia and visual loss. Examination shows decreased visual acuity, lid edema, proptosis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, extraocular motility disturbance, increased intraorbital (resistance to retropulsion) and intraocular (tonometry) pressure and an afferent pupillary defect (Fig. 34.2).

Fig. 34.2 Retrobulbar hemorrhage producing ecchymosis after a frontal nerve block during transcutaneous blepharoplasty (A) and retrobulbar hemorrhage in a hypertensive patient demonstrating sudden proptosis and chemosis (B).

Pearls

Pearls to avoiding retrobulbar hemorrhage include:

• Detailed preoperative evaluation with particular attention to medical problems such as diabetes, hypertension, coagulopathies and both prescription and over-the-counter anticoagulant medication use. Stopping all anticoagulants far enough in advance to allow normalization of bleeding parameters and platelet function is important.

• A past ocular history is necessary to rule out pre-existing causes of visual dysfunction, as rare reports of malpractice cases where patients have claimed pre-existing visual loss as a consequence of blepharoplasty do exist.

• Intraoperative control of hemostasis is critical. Koorneef’s description of the delicate connective tissue scaffold connecting the anterior orbital fat to deep orbital fat underscores the necessity to avoid excessive traction during fat excision. It is advantageous to delay wound closure by proceeding to another surgical site, returning later to reassess hemostasis prior to suturing.

• Postoperative prevention of hemorrhage involves all of the following:

Once the diagnosis of retrobulbar hemorrhage is made, the treatment requires immediate attention. The first step should be to identify those hemorrhages that require medical or surgical care, based on the ophthalmic examination. If the intraocular pressure is elevated, as measured by tonometry or emergently by tactile evaluation, topical and systemic glaucoma medications can be used. Systemic corticosteroids are used for significant edema. When the bleeding threatens the visual system, or is worsening, surgical therapy is required. The first step is to open the incision widely through the orbital septum and explore the surgical site and orbit for signs of bleeding. Clots are evacuated and cautery is applied when bleeding sites are identified. If the condition remains unresponsive, a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis is performed. In severe cases, both the inferior and superior crus of the lateral canthal tendon can be released. When these measures fail, an emergent CT scan without contrast is warranted. If posteriorly organized hemorrhage is identified, bony decompression may be warranted to relieve orbital apex compression (Fig. 34.3). The treatment should be aggressive for the first 24–48 hours postoperatively, as vision has been reported to return in patients with “no light perception” that was present for 24 hours.

Globe perforation

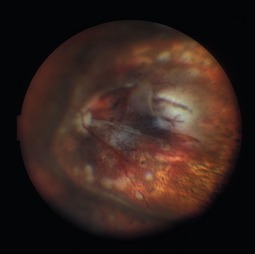

Inadvertent globe penetration can result from any periocular procedure. Caution is necessary during local anesthetic injection, particularly in the thin upper eyelid of older patients. Prevention of this complication begins with the use of protective corneal shields during injection and surgery. Corneal shields should be lubricated with ophthalmic ointment prior to placement within the lids to avoid corneal abrasion. The range of potential ocular damage from penetration includes an open globe, corneal perforation, traumatic cataract, intraocular hemorrhage, a hypertensive or hypotensive globe, retinal tears and detachment (Fig. 34.4). Perforation of the globe is an ophthalmic emergency and necessitates emergent consultation with an ophthalmologist. A Fox shield should be placed over the eye in the interim and the patient should be instructed not to rub or press on the eye.

How to place a corneal protective lens:

• Instill a tetracaine or proparacaine ophthalmic eye drop into the eye.

• Lubricate the protective shield with ophthalmic ointment.

• Insert the shell under the superior fornix from below.

• Evert the lower eyelid to allow the lower edge of the shell to move into the inferior fornix.

How to remove a corneal protective lens:

Corneal abrasion

Corneal abrasion is generally a rapidly reversible cause of decreased vision postoperatively. The diagnosis is made by patient symptoms (pain, foreign body sensation, light sensitivity) and is usually apparent immediately after surgery. The diagnosis is confirmed by evaluating the cornea under a cobalt blue light after instillation of fluorescein (Fig. 34.5). Even though corneal abrasion is the leading cause of ocular pain and irritation following blepharoplasty, patients who complain of severe eye pain should be carefully examined under a slit-lamp to rule out globe perforation. Abrasions are often caused by drying of the corneal surface during surgery or inadvertent damage to the surface corneal epithelial layer. Sometimes, taping of the eyes during anesthetic induction causes an abrasion if the eyes are accidentally taped in an open position. Careful insertion and removal of well-lubricated corneal shields prevents this complication; as does the use of ophthalmic ointment into each eye at the completion of the procedure. Abrasions can be treated with ophthalmic antibiotic ointment four times daily, and should be resolved within 24 hours. Patching should be avoided, as it may mask a more serious complication, such as retrobulbar hemorrhage. Persistent signs and symptoms should prompt ophthalmologic evaluation.

Dry eye

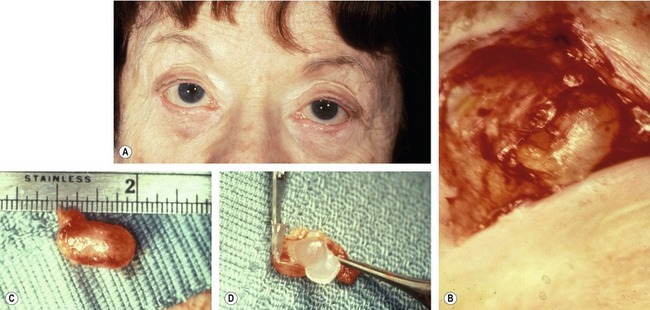

Very rarely, ophthalmic lubricant may be inadvertently introduced into deeper eyelid tissues from a transconjunctival surgical wound. This can result in encapsulation of the ointment within the wounds, and subsequent cyst formation that responds to excision (Fig. 34.6). Although this complication is extremely rare, physicians should keep in mind that excessive amounts of ointment are unnecessary and may result in inoculation of the wound.

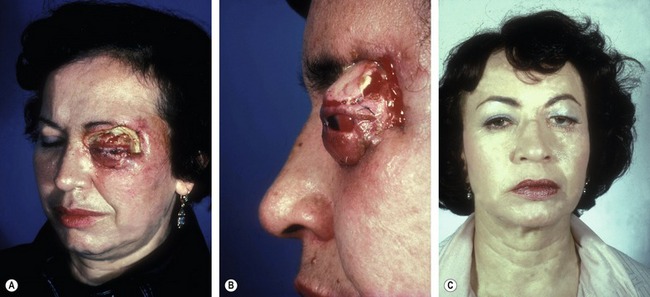

Infection

The development of cellulitis or abscess formation is exceedingly rare in the well-vascularized eyelid. Nonetheless, both complications have been reported and should be managed with appropriate oral or intravenous antibiotics. Abscesses require surgical drainage. Figure 34.7 shows a patient who developed pseudomonas cellulitis in three of four lids after blepharoplasty. She was treated with a combination of surgical drainage and intravenous antibiotics, but ultimately developed late cicatrization and skin dimpling.

Eyelid sloughing

Eyelid necrosis has been reported sparingly in the literature and can follow inadvertent injection with formaldehyde or other substances (i.e. atropine, alcohol, boric acid) instead of local anesthetic. Complete eyelid sloughing can develop, necessitating multiple eyelid reconstructive procedures and setting the patient up for scarring, persistent lagophthalmos and chronic ocular irritation from dry eye (Fig. 34.8).

Chemosis

Conjunctival edema can develop in the early or intermediate postoperative period as the result of incomplete eyelid closure, ocular allergy, sinusitis or surgical edema. Chemosis can be worsened by systemic conditions, such as renal failure (Fig. 34.9). Corneal drying may occur, as the edematous conjunctiva balloons around the cornea preventing adequate tear film dispersion. Additionally, the exposed conjunctival surface may keratinize, leading to worsening foreign body sensation and ocular irritation. Treatment is with preservative-free artificial tears and ointment. A mild topical steroid eye drop can be prescribed, but should only be given in conjunction with ophthalmic evaluation to assure normalcy of the intraocular pressure and to rule-out secondary infectious keratitis. Rarely, a temporary suture tarsorrhaphy may be needed.