Treatment for Varicose and Telangiectatic Leg Veins: Introduction

|

Introduction

Bulging varicose veins and unsightly “roadmap” telangiectatic webs affect millions of patients around the world. The incidence is highest in Caucasian patients in which telangiectasias comprise the most common of all cosmetic complaints. This is borne out by epidemiologic surveys in which leg telangiectasia are reported in 70% of women.1 These same 24 city studies of thousands of patients indicate that 53% of the population over 50 years of age show some venous reverse flow.1 Women are at least 4 times more likely than men to develop telangiectasia, while males have double the risk of developing large varicose veins.2 Women aged over 50 years are five times more likely than women aged 29 or less to develop large varicose veins. Pregnancy increases the risk of varicose vein development by a factor of 1.5× to 3× and is associated with higher risks following three pregnancies.1,3,4 Increased body mass index correlates with a higher risk of reverse flow or reflux which leads to pain, swelling and abnormalities of the saphenous system.5,6 A positive familial history of disease is well known to increase the risk for varicose veins. Varicose veins may cause significant morbidity including chronic stasis dermatitis, ankle edema, spontaneous bleeding, superficial thrombophlebitis, recurrent cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis and skin ulceration on the ankle and foot.

The incidence of varicose veins increases with each decade of life. Increased incidence has led to increased demand for treatment of varicose and telangiectatic veins as the average age of the US population grows. While 41% of women in the fifth decade have varicose veins, this number rises to 72% in the seventh decade.7 Statistics for men are similar with 24% incidence in the fourth decade, increasing to 43% by the seventh decade. Six million workdays per year may be lost in the United States due to complications of varicose veins, although this number is being affected by endovenous ablation techniques.8 Treatment is now much less complicated as an outpatient procedure avoiding dreaded stripping. As such noninvasive treatments are more frequently utilized so that lost workdays may actually be decreasing, although these statistics do not exist.

The main techniques employed in the dermatologist’s office for treatment of cosmetic spider veins are sclerotherapy and lasers. For larger varicose veins, dermatologic surgeons employ sclerotherapy (with or without Duplex ultrasound guidance), ambulatory phlebectomy, and endovenous ablation by radiofrequency or laser. Sclerotherapy, which is defined as the intravascular introduction of a sclerosing substance, is the most frequently utilized procedure. We recommend that the term be changed to “endovascular chemoablation” which more accurately describes the procedure, although sclerotherapy is so entrenched that this will be unlikely to occur.

Sclerotherapy gained acceptance in the United States as a highly effective treatment during the early 1990s as it can be utilized for veins of all sizes.9 With the addition of foaming the sclerosant, utility has been expanded further.10 Sclerotherapy is also an important adjunctive therapy to surgical techniques such as ambulatory phlebectomy for saphenous tributaries11,12 and endovenous ablation of refluxing saphenous veins.13,14 Knowledge of venous anatomy and physiology, principles of venous insufficiency, methods of diagnosing venous abnormality, uses and actions of sclerosing solutions and proper use of compression are essential elements of successful venous therapy.

Historical Aspects

Primitive stripping and cauterization were practiced by Celsus, while ligation was mentioned by Antillus (30 ad). In the second century ad, Galen proposed tearing out the veins with hooks, a precursor to the modern day technique of ambulatory phlebectomy originated by Swiss dermatologist Robert Muller in the late 1960s.

A crude concept of sclerotherapy appeared in 1682, as Zollikofer described injection of acid into a vein to create a thrombus. By the late 1700s, the critical role of saphenofemoral reflux in the pathogenesis of varicose veins had been recognized by a Swiss surgeon, Rima. Reports of use of absolute alcohol as a sclerosing agent appeared from 1835–1840. In 1851, Pravaz attempted sclerotherapy with ferric chloride using his new invention, the hypodermic syringe.

The foundation of modern sclerotherapy can be traced to World War I when Linser and Sicard both noticed the sclerosing effect of intravenous injections used to treat syphilis which often resulted in vein sclerosis. Tournay greatly refined the sclerotherapy technique in Europe. It was not until 1946, when a safe sclerosant, Sotradecol (sodium tetradecyl sulfate) had been tested and described that sclerotherapy began to be seriously studied in the United states.15

Another key to success and acceptance of the treatment of varicose veins by sclerotherapy was the addition of compression. Sigg and Orbach in the 1950s and Fegan in the 1960s emphasized the importance of combining external compression immediately following injections. Starting in the 1980s, Duffy promoted the technique among dermatologists and advocated the use of polidocanol (POL) and hypertonic saline as safe and effective sclerosing solutions.16 In March 1999, the first endovenous obliteration technique utilizing radiofrequency was cleared by the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). Dermatologic surgeons were instrumental in developing this technique.14,17,18 Goldman’s first American textbook of sclerotherapy integrated the world’s phlebology literature, introduced new sclerosing solutions and validated dermatology’s claim to expertise in vein treatment.19 Several additional textbooks by dermatologic surgeons have firmly established phlebology within the domain of dermatology.20,21 The newest development in sclerotherapy has been the FDA approval of polidocanol (Asclera, Merz Aesthetics/Bioform, San Mateo, CA) in late spring of 2010. The advantages of this solution are discussed later.

Patient Selection—Venous Anatomy and Physiology, Symptoms, and Contraindications

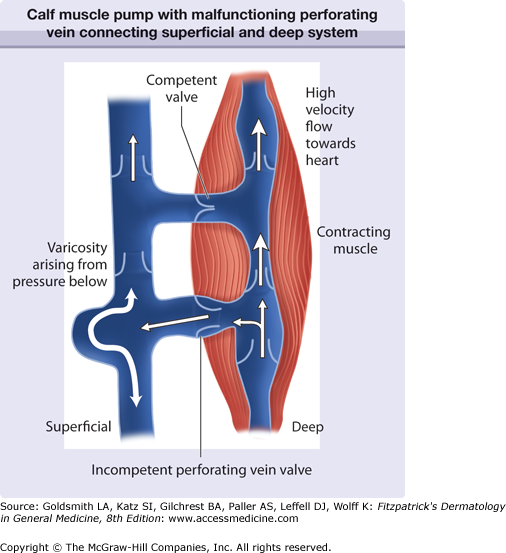

The venous system is comprised of a primary deep venous compartment and superficial compartment with thousands of small veins (perforating veins) connecting the two systems. The deep compartment, “the muscle pump,” normally acts as a conduit for 85%–90% of venous return from the leg. During contraction of the calf muscles, the valves of the perforating veins and associated superficial veins close, allowing blood to flow only proximally at high pressures through the deep system. This generates primary propulsive force returning venous blood to the heart (Fig. 249-1).

Figure 249-1

Schematic of the calf muscle pump with malfunctioning perforating vein connecting the superficial and deep system. High pressures are generated when the gastrocnemius muscle contracts to pump blood proximally. A malfunctioning valve is shown diverting pressure to the skin surface. Competent valve directs flow proximally.

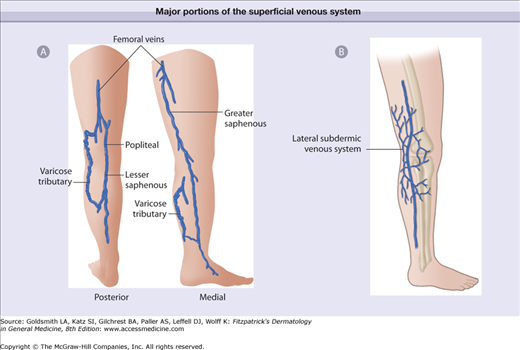

The superficial venous system consists of three primary territories: (1) great saphenous vein (GSV) (2) small saphenous vein (SSV) and (3) subdermic lateral venous system (LVS) (Fig. 249-2). Comprising the three major patterns are multiple collateral veins (accessory) and multiple tributary veins emptying into all 3 major superficial systems of the GSV, SSV and LVS. The points of connection (perforating veins) between the superficial and the deep system play important roles as these are sites through which reflux or reverse flow often develops (Fig. 249-3). Due to gravitational hydrostatic pressure, sequential retrograde breakdown of venous valve function often follows a leak at one point leading to propagation of a varicosity. Increased diameter between valve leaflets with failure to oppose properly caused by genetically weak venous wall or venous valve structure may initiate these events. Calf muscle pump pressure plus gravitational hydrostatic forces are transmitted directly via the incompetent perforating vein or communicating veins to the surface veins. Venous hypertension may reach levels higher than systolic arterial blood pressure in the cutaneous venules with the patient erect. Transmission of pressure may result in venular dilatation over a wide area of skin including the formation of telangiectatic webs and more serious consequences such as ulceration.22 This leads to a number of symptoms with heaviness, fatigue, and aching of the legs.23

Figure 249-2

Schematic of the major portions of the superficial venous system. A. Greater saphenous vein and lesser saphenous vein. B. Subdermic lateral venous system. When varicosities or telangiectatic webs are present within the distribution of these saphenous veins, the source of pressure must be elucidated. The lateral venous system is the most common source of telangiectasias.

When present in significant quantity, the volume of blood sequestered and stagnant in reticular veins and associated telangiectatic webs (particularly of the lateral venous system) may cause enough distention to produce symptoms.24 Symptoms are relieved by the wearing of support hose or with rest and elevation of the legs. Prolonged standing or sitting without calf muscle contraction worsens symptoms. The size of the vessels causing moderately severe symptoms may be as small as 1–2 mm in diameter. Sclerotherapy has been reported to yield an 85% reduction in these symptoms as well as superb cosmetic results.24

Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

Pain | Reflux at saphenofemoral or sahenopopliteal junctiona |

Major tributaries of greater and lesser saphenous veins | Nonambulatory patient |

Major perforator reflux | Obesity |

Lateral venous system varicosities | Deep venous thrombosis |

Cosmetic | Known allergy to sclerosing agent Arterial obstruction Pregnancy |

Vein treatment and, in particular, foam sclerotherapy may be performed safely and effectively in virtually all types of veins, except when reflux exists at the saphenofemoral junction. Since the goal of sclerotherapy is to eliminate reflux at its origin, the goal of noninvasive diagnostic evaluation is to uncover primary sources of high reverse flow pressure. A high rate of recurrence for sclerotherapy is commonly seen when reflux originates at the major saphenous junctions. The techniques of endovenous ablation by radiofrequency or laser are the means by which reflux occurring at the termination point of the saphenous veins is now treated. Five-year data indicates that these techniques are as effective as the old surgical techniques of ligation and stripping to eliminate saphenous veins.25 Our experience at ten years show that these techniques are superior to older surgical techniques. Recent studies show high recurrence rates (30%–50%) following ligation and stripping.26 Archaic and invasive stripping techniques are no longer recommended for primary treatment of saphenous reflux. Endovenous ablation techniques have been embraced due to the high degree of safety and efficacy, without morbidity and downtime of general anesthesia and invasive technique required by stripping.27

Venous treatment is contraindicated in a bedridden patient since ambulation is important for minimizing risks of thrombosis. Similarly, patients under general anesthesia for nonrelated procedures should not undergo simultaneous sclerotherapy. Severely restricted arterial flow to the legs necessitates postponement of vein treatment. A history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or previous trauma to the leg (e.g., auto accident) should preclude sclerotherapy until adequately evaluated by Duplex ultrasound. Previous urticaria or suspected allergy to a sclerosing agent should serve as a relative contraindication to use of that particular sclerosing agent.

Pregnancy should be considered a contraindication during the first and second trimester, although extremely painful or bleeding, varices may be treated in the last trimester by endovenous ablation techniques. Treatment is typically postponed since varicosities and telangiectasias may resolve spontaneously 1–6 months postpartum.

Obesity should be considered a relative contraindication since maintaining adequate external compression is difficult. Sclerotherapy of larger varicosities should be postponed until weight reduction is achieved. During hot summer months, heat-induced vasodilatation and inability to comply with wearing of compression hose may also require postponement of treatment.

Treatment Techniques

Physical examination is performed by viewing the patient’s legs in a 360° rotation. Palpation is performed along the saphenous vein distributions to rule out early large axial varicosities which cannot be seen. Based on the history and physical examination, noninvasive diagnostic vascular tests are performed as necessary.28 Those patients with a family history of large varicose veins are more likely to have early axial (saphenous) reflux even when presenting with telangiectasias alone.11 Previous venous surgery warrants further testing before treatment.

Once the patient is judged to be a candidate for vein treatment, informed consent is obtained. Any veins visible or palpable suggestive of saphenous system involvement should be minimally evaluated by handheld Doppler ultrasound, which is equivalent to using an enhanced “stethoscope” to hear vein flow. It is generally recommended to supplement Doppler with Duplex ultrasound as this method of visualization of venous anatomy is more reliable and more prevalent. For Doppler to generate or augment an audible signal of flow, a maneuver such as manual compression of the calf must be performed by the examiner. When compression is released, gravitational hydrostatic pressure causes reverse flow to cease within 0.5–1 second when valves are competent, but a long flow sound is audible when valves are incompetent.

The most essential part of the Doppler examination is the examination of the saphenofemoral junction below the inguinal fold just medial to the femoral arterial signal. During a Valsalva maneuver, a continuous and pronounced reflux signal is a reliable sign of valvular insufficiency. An equivocal result may require a duplex ultrasound examination for a definitive answer. Methods of complete Doppler examination are detailed in other texts.11

The gold standard of noninvasive examination of the venous system is duplex ultrasound. This allows direct visualization of the veins and identification of flow through venous valves. An image is created by an array of Doppler transducers, which are switched on and off sequentially. The Duplex examination is often used to uncover hidden sources of reflux prior to beginning any method of treatment or delineate reflux sources when patients experience poor results from sclerotherapy. The declining price and increasing portability of Duplex ultrasound is rapidly making this examination the standard and reducing Doppler ultrasound to a relic of the past.

Sclerosing solutions have been classified into groups based on chemical structure and effect: hyperosmotic, detergent, and corrosive agents (chemical toxins—salts, alcohols, and acid or alkaline solutions). Commonly employed sclerosing solutions are summarized in Table 249-2.

Sclerosing Solution | Category | Advantages | Disadvantages | Vessels Treated | Concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sodium tetradecyl sulfate (Sotradecol) | Detergent | FDA approved Painless—unless injected extravascularly | May cause breakdown rarely—rare allergic reaction | All sizes | 0.1%–0.2% telangiectasias 0.2%–0.5% reticular 0.5–1.0% varicose 1.0–3.0% axial varicose |

Polidocanol | Detergent | Painless Low ulceration risk at low concentrations—low skin toxicity | Not FDA cleared until 2010 Rare allergic reaction | Small to medium | 0.25–0.5% telangiectasias 0.5%–1.0% reticular 1.0%–3.0% varicose |

Hypertonic saline | Hyperosmolar | Low risk of allergic reactions | Ulcerogenic Painful to inject | Small | 23.4%–11.7% telangiectasias 23.4% reticular |

Hypertonic saline + dextrose (Sclerodex) | Hyperosmolar | Low risk of allergic reaction Mild stinging Low ulcerogenic potential | Not FDA approved Relatively weak sclerosant | Small | Undiluted–telangiectasias Undiluted–reticular |

Sodium morrhuate (Scleromate) | Detergent | FDA approved | Allergic reactions highest | Small | Undiluted–telangiectasias Undiluted–reticular |

Chromated glycerine (glycerine with 6% chromium salt (Scleremo) | Chemical irritant | Low skin ulcer potential | Not FDA approved Very weak sclerosant | Smallest | Undiluted to strength–telangiectasias |

Glycerine – plain | Chemical irritant/hyperosmolat | Painless, low-risk or allergic reaction, decreased risks of pigmentation and matting | FDA approved for reduction of cerebral edema | Smallest | 50%–72% |

Polyiodinated iodine (Varigloban) | Chemical irritant | Highly corrosive—allows treatment of largest veins | Not FDA approved Avoid in iodine allergic patients painful to inject | Largest | 1%–2% for up to 5mm veins 2%–6% for the largest veins |

Although approved by the FDA only for use as an abortifacient, it is still commonly used in the United States in spite of its shortcomings. Used at a concentration of 23.4% (HS), a theoretical advantage of HS is its total lack of allergenicity when unadulterated. HS has been commonly used in various concentrations from 10% to 30%, with occasional addition of heparin, procaine, or lidocaine. Additional agents typically provide no benefit. Therefore, HS is used either unadulterated or diluted to 11.7% with sterile water for smaller telangiectasias.29

With hypertonic solutions, damage of tissue adjacent to injection sites may easily occur. Skin necrosis may be produced by extravasation at the injection site, particularly when injecting very close to the skin surface. Injection of hyaluronidase into sites of extravasation may significantly reduce the risks of skin necrosis with HS.30 The pain of injection with risks of ulceration of this solution, makes it highly undesirable for modern vein treatment. We strongly recommend against the use of HS, especially with newer safer and less painful sclerosing agents approved by the US FDA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree