Transumbilical Breast Augmentation

Richard V. Dowden

Marianne A. Fuller

History and Background

Attempts to find a procedure to satisfy a woman’s desire for larger breasts without a breast incision have a long history. Inserting breast implants during operation upon the abdominal wall was reported in 1976 by Planas (1) and again in 1980 by Barrett (2). The idea of inserting breast implants through the navel was conceived and developed by Johnson in 1991 and published soon thereafter, revealing a very low complication rate (3). Subsequent to the initial publication the procedure has undergone several significant modifications (4,5,6), has been proven safe and effective both for patients (7) and for implants (8), is now widely used (9,10,11,12,13,14), and has become an integral part of the standard of care. Transumbilical breast augmentation makes use of established techniques with which most plastic surgeons are familiar, such as suction-assisted lipectomy, operative endoscopy, and tissue expansion, but which are combined in a way that was novel 16 years ago.

A few words are in order concerning terminology. The accepted correct term is transumbilical breast augmentation (TUBA). Other terms have been suggested but have been rejected for inaccuracy, such as “periumbilical” or “transabdominal.” These are misleading and should be discarded. Just as transaxillary means through the axilla, transumbilical means through the navel—peri means around, and neither periumbilical nor periaxillary would be correct. Transabdominal is worse, because it implies a procedure done through the abdominal cavity, still an occasionally encountered misconception. Even when the incision is made through an abdominal scar or when the procedure is done during an abdominoplasty, the term TUBA should be used because what most distinguishes this method from all others is the unique set of technical principles involved rather than the precise location of the incision.

Except for the scar, the transumbilical approach produces final results not unlike the successful results of any other method of inserting saline-filled implants, but the TUBA has a few distinct advantages over those other methods (15). Those who perform the procedure have consistently noted a low rate of complications, minimal pain, a fast recovery, and very high patient satisfaction. Our experience has reflected those observations as well. Most important, we find that especially for asymmetric breasts, TUBA gives the best control over the final position, shape, and symmetry of the breasts. The recovery is remarkably rapid after the TUBA procedure, especially if prepectoral. As the choice of prepectoral or subpectoral is left to the patient, it is not surprising that patients are equally satisfied with the results of the plane they chose. The consistently minimal bleeding with the TUBA procedure is probably due to the fact that there is no cutting in, or behind, the breast (3). The remarkably low level of pain after the transumbilical augmentation has not been fully explained, but one hypothesis is that the implant is exerting no tension upon the healing incision; that characteristic is of course shared with transaxillary augmentation, but the TUBA has the added advantage over the transaxillary approach that the incision is located in an immobile area not moved or stretched by arm raising. Another advantage of TUBA is the surgeon’s freedom to use quite large implants without fear of a wound dehiscence or symmastia, despite the considerable tension that may be exerted on the breast skin.

The TUBA is a blunt expansion technique, requiring no cutting and no cauterization within the pocket. It does not require insertion of gauze or sponges inside the pocket, avoiding the chance of retention thereof. Some authors (16) have speculated that such blunt expansion might result in more pain than cutting or cautery techniques, yet that hypothesis has been disproven in practice. Of course, assessment of patient pain levels is highly subjective, and attempting to compare pain levels between different incisions is nearly impossible; moreover, it is highly unlikely that any true controlled study can or will ever be done.

Another advantage of the TUBA method pertains to drains. Many surgeons believe that serosanguineous fluid collections around the implants may be a major factor leading to capsular contracture. For this reason, some advocate use of drain tubes, while others avoid doing so because they are uncomfortable with the concept of a drain connecting the skin to the surface of the implant. One advantage of the TUBA procedure is that the tunnels provide a dependent reservoir for any seroma that might otherwise collect around the implant, or at least provide a location for drain tubes that need not be in contact with the implants.

The TUBA method has some advantages in terms of implant protection. Manufacturer representatives are well aware of four types of potential intraoperative damage to implants, which can occur with any augmentation technique: damage from use of an implant as a tissue expander, contact with sharp-edged instruments, rupture during forced insertion of filled implants, and needle puncture during closure. These modes of injury cannot occur with the TUBA technique, in which the implants are not used as expanders, the implants do not contact any instruments, the implants must be empty when inserted, and the closure sutures are far distant from the implant.

If the TUBA has so many advantages, one might ask, why have not more surgeons learned how to perform it? Several possible reasons include that surgeons may be afraid to learn something new or may be wary of something unfamiliar, or they may see no justification for expanding their current practice methods in light of the cost of the equipment and the time needed to learn the TUBA technique. It is conceivable that some surgeons may be resentful that someone else has devised an excellent method that they cannot offer the patient and wish to hold on to their established methods. Perhaps it is an example of the maxim due to Thomas Szasz stating that “Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an

injury to one’s self-esteem” (17). It is historically noteworthy that negativity and reluctance also attended the introduction of endoscopic methods for performing other traditionally open procedures, such as cholecystectomy, splenectomy, hernia repair, and carpal tunnel, to name but a few of the hundreds of procedures now done primarily endoscopically.

injury to one’s self-esteem” (17). It is historically noteworthy that negativity and reluctance also attended the introduction of endoscopic methods for performing other traditionally open procedures, such as cholecystectomy, splenectomy, hernia repair, and carpal tunnel, to name but a few of the hundreds of procedures now done primarily endoscopically.

Another possible reason for reluctance to learn the TUBA method may be a lack of the requisite endoscopic ability or at least a lack of understanding of the way the endoscope is used for transumbilical breast augmentation. In any breast enlargement technique there must be adequate visualization to ensure that the critical portions of the procedure are done correctly and safely (18). In some techniques, this is accomplished by direct vision using lighted retractors, and in other techniques this visibility is enhanced by use of endoscopes. If the navel is chosen, implant plane and orientation, absence of bleeding, adequacy of pocket formation, and valve integrity can be verified only through the use of an endoscope. Therefore, proper performance of the TUBA procedure requires that the surgeon possess strong endoscopic skills. The surgeon must be comfortable relating what the hands are doing to what is seen on the monitor and relating the monitor view to the reality of the anatomy (19). It is important to note that, in contrast to every other endoscopic breast procedure, in the transumbilical augmentation the endoscope is not used during pocket formation, for which internal hydraulic expansion is used instead, with external monitoring by observing the position and shape of the breasts. The endoscope is only used at key points to verify the status of the pocket. Nevertheless, there are some surgeons who perform the TUBA without an endoscope in order to shorten the operating time; this is inadvisable. In addition, it would be a mistake to change the procedure to one involving sharp dissection under endoscopic visualization, as has been suggested from time to time by various surgeons not thoroughly conversant with the TUBA technique.

Many surgeons are under the misconception that using endoscopic techniques might void the implant warranty. This is a false assumption based on the implant brochures, which state that the manufacturers do not recommend the transumbilical or any other endoscopic method (which therefore precludes transaxillary as well). A little history is in order concerning that unfortunate implant brochure wording. At the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) implant approval hearings, the TUBA procedure was mentioned briefly in passing. Although there were two plastic surgeons present, unfortunately neither was knowledgeable about TUBA. Due to the absence of information, the FDA committee members heard a false statement that implants are “wadded up and shoved in through an endoscope” (20), and as a result of that misunderstanding it was suggested by one of the plastic surgeons that the FDA not approve endoscopic methods, which in turn led to the inappropriate wording in the brochures. Federal law prohibits the manufacturer from recommending that any product be used “off label,” that is, in any manner not approved by the FDA. Because the manufacturers cannot recommend the transumbilical approach, one might think that the plastic surgeon might be barred from using the TUBA or axillary approaches. In fact, however, there is no legal obstacle to a physician using any product in an off-label application (21). Therefore, there are no legal limitations on plastic surgeons regarding the TUBA procedure. When performed as specified in this chapter, there would be no basis for voiding the warranty, and in fact the manufacturers have continued to honor their warranties. More to the point, both of the U.S. manufacturers whose implants are FDA approved have provided written assurance that their implant warranties are fully in effect after using the transumbilical approach (22), and both manufacturers provide extra-long fill tubes specifically designed for the TUBA method.

The TUBA method has been the subject of a variety of other criticisms. Careful examination of each of those criticisms reveals that most are at best misconceptions, or at worst intentional falsehoods (19), but in any case all are unquestionably false. Some of the worst misunderstandings need to be clarified. The entire TUBA procedure takes place external to the anterior rectus fascia, in the subcutaneous plane, and does not involve abdominal muscles, the abdominal cavity, or internal organs. No actual cutting takes place behind or within the breast. The surgeon is able to see externally the exact shape of the breasts, as well as the position of the implants, during the expansion phase, so there is no guesswork involved in pocket formation or implant positioning. Implant pocket creation is actually easier than with any other method. We find that the TUBA method facilitates correction of breast asymmetry, and modest degrees of tubular breasts as well, because of the ability to pressure expand the skin without fear of dehiscence.

Surgeons who intend to offer the TUBA method must be prepared to counter with true information all such false criticisms that the patients may have heard or read. These criticisms generally originate from surgical colleagues, and are usually just an indication of ignorance about the procedure, although in some instances they could represent a desire to discredit the TUBA method. For example, some surgeons disparage this blunt expansion technique by describing it using emotionally charged negative terms intended to alarm patients. They use terms such as “ripping” or “tearing” or “avulsing,” despite the time-honored role of blunt techniques in other commonly performed procedures such as face lift, abdominoplasty, rhinoplasty, and liposuction, in connection with which those same surgeons do not use such pejorative terms. Surgeons may also attempt to cast aspersions on the TUBA by saying that it is a “blind” technique, ignoring the fact that we commonly perform other blind techniques such as rhinoplasty and liposuction, in which progress is assessed externally rather than from the inside. Patients need clear information to counteract such misguided influences.

Having said all that, the legitimate disadvantages of the TUBA procedure also warrant discussion. The TUBA cannot be used for prefilled implants, silicone or saline, because the atraumatic insertion of implants through a narrow passageway and their confinement within the appropriately dimensioned pocket require the ability to shape them into a small cross section for insertion. A method for inserting silicone gel implants transumbilically may be developed in the future, as research is ongoing toward that end. Another drawback is that the TUBA method may be less than ideal for placement of nonround implants because creating the appropriate nonround pocket might be difficult, possibly increasing the chance of later rotation, but here too research is being done.

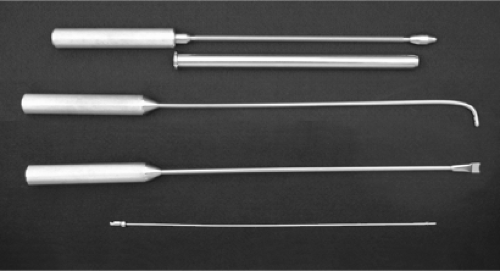

One disadvantage of the TUBA procedure is the need for a significant investment in equipment not otherwise required for breast augmentation, including the endoscope, video camera, monitor, light source, Johnson instrument set (Fig. 114.1), and two full sets of intraoperative expanders. The endoscope is a standard 10 mm × 34 cm–long, rigid, 0-deg nonoperating

gynecology type. Note again the key principle that there is no dissection taking place under endoscopic view, only verification at key points during the procedure, hence the nonoperating scope.

gynecology type. Note again the key principle that there is no dissection taking place under endoscopic view, only verification at key points during the procedure, hence the nonoperating scope.

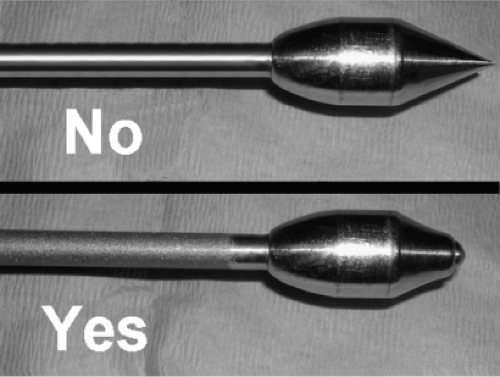

Johnson instrument sets can be obtained directly from the Wells Johnson Company (Tucson, AZ). They offer two different calibers of tube and obturator, a 19-mm and a 24-mm outside diameter. We use the 19-mm size for almost all implants, but the 24-mm size may be needed for the larger Allergan implants, which are somewhat bulky when rolled. The Johnson tube and matching obturator are essential for establishing the correct plane of placement and for endoscopic verification at critical points during the procedure. To maximize safety, we strongly contend that the obturator tip should be slightly blunt rather than sharply pointed (Fig. 114.2), which may require that some modification be performed. The Johnson hockey stick, a long, blunt rod bent at the end, with blunt notches near the tip, is also used on every case. We use the straight, notched pusher about once every 50 cases to push a fibrous band out of the way. A long, thin (3/32 inch) suction tube, blunt at the tip with a locking connector, is part of our set as well; although not part of the standard set, it can be supplied by Wells-Johnson. It is important to note here that the Johnson tube is not used to push the implant into position as was portrayed in the original publication (3). Of course, it never was recommended to pass the implant through any instrument, the erroneous FDA testimony to the contrary. It is sufficient, and safer, for the implant to be advanced solely by external manipulation by the surgeon.

In the original description of the technique (3), the implant itself was used as the device that initially overexpanded the pocket, which was then left in place. To avoid expansion trauma to the implants, the procedure was changed in 1992, requiring a preliminary step to create the pocket using strong, saline-filled expanders. These expanders permit precise and symmetric development of the pockets and are then removed. The expanders used should have the same volume and dimensions as the implant. Usually, except in highly asymmetric patients, the expanders are not used as “sizers” to decide which implants are to be used, a decision that is best made in advance. The expander is generally inflated to 150% to 170% of final volume for prepectoral and from 150% to 200% for subpectoral placement; the greater levels of temporary overinflation are used if the skin envelope is very tight. The expanders should be transparent, not opaque, in order to permit inspection of the interior of the pocket through the expander itself. If no transparent expanders are available, a set can be easily fabricated by taking standard smooth implants and securely bonding their fill tubes using a commercial grade of room temperature–curing silicone adhesive and then heating in an autoclave.

Far more important than the instrumentation, the main prerequisite for the TUBA technique is proper training of the surgeon. The TUBA is not a procedure to be attempted on the basis of reading articles or books, attending lectures, and watching a few cases. Once mastered, the TUBA procedure is very safe and straightforward, but the learning curve can be steep, and there are many ways that an inadequately trained individual can get into problem situations. Proper training includes lectures, visual aids, endoscopic practice, and cadaver lab sessions, as well as an extensive review of videotapes about the recognition and management of potential problems. It is worth reemphasizing that endoscopic skill is an absolute requirement for performing this ingenious and effective procedure safely and well (4).

Out of 2,796 breasts that we originally augmented via the navel, we reoperated on 117 breasts (4.1%), most via the navel, chiefly for size change, and other indications as listed in Table 114.1. On a patient basis, 4.4% of patients were reoperated, over half being elective patient choice.

Patient Selection

In our practice, once it has been determined which incision locations would be feasible for her, the patient decides on the incision site. Nearly all patients are suitable candidates for the transumbilical approach, even those with significant deformity of the chest wall and those with a flared rib cage, as well as those who have pectus excavatum or carinatum. It is suitable for augmenting breasts with moderate degrees of tubular breast deformity, and contrary to popular folklore, the TUBA is

excellent for correcting breast asymmetry. As opposed to an opinion in the literature (11), we have had no problem lowering the inframammary fold, even as much as 3 cm. Use of the TUBA simultaneously with a mastopexy has not yet been reported, but it would be possible. Some might argue that since a mastopexy would require incisions on the breast anyway, doing a TUBA procedure would have little merit. However, doing the TUBA first would permit accurate assessment of the degree of remaining ptosis without the distortion produced by a fresh breast incision. The “tailor-tack” approach could then be done without concern that any subsequent flap necrosis would necessarily expose the implant. It is noteworthy that prior breast surgery has not interfered with the TUBA technique; we have used the TUBA method for patients who had prior biopsies, mastopexies, explantations, radiation, and breast reduction surgery. Less ideal candidates for TUBA include those with severe tubular breast deformity or those whose nipples require relocation, because for them a great deal of modification of the surface of the breast would be required.

excellent for correcting breast asymmetry. As opposed to an opinion in the literature (11), we have had no problem lowering the inframammary fold, even as much as 3 cm. Use of the TUBA simultaneously with a mastopexy has not yet been reported, but it would be possible. Some might argue that since a mastopexy would require incisions on the breast anyway, doing a TUBA procedure would have little merit. However, doing the TUBA first would permit accurate assessment of the degree of remaining ptosis without the distortion produced by a fresh breast incision. The “tailor-tack” approach could then be done without concern that any subsequent flap necrosis would necessarily expose the implant. It is noteworthy that prior breast surgery has not interfered with the TUBA technique; we have used the TUBA method for patients who had prior biopsies, mastopexies, explantations, radiation, and breast reduction surgery. Less ideal candidates for TUBA include those with severe tubular breast deformity or those whose nipples require relocation, because for them a great deal of modification of the surface of the breast would be required.

Table 114.1 Reoperated Breasts (117) | |

|---|---|

|

We have encountered no difficulty from abdominal scars due to C-sections, liposuction, abdominoplasties, laparoscopies, or laparotomies, including scars that actually cross the paths of the tunnels, such as from cholecystectomy, gastrectomy, or splenectomy. For many of our patients with abdominal scars it has even been straightforward to use those scars rather than make a navel incision. Patients with scleroderma have posed no obstacle even when a patch of atrophic sclerodermatous skin lies directly over the path of the tunnels. One contraindication to the TUBA procedure is an upper abdominal hernia positioned in the path of the tunnels and likely to interfere with passing the obturator. Obesity per se is not a contraindication to the TUBA procedure, but if a patient’s abdominal fat layer were too thick to permit detection of such an upper abdominal hernia, she would not be a candidate without further studies to exclude such a hernia. An umbilical hernia is not a contraindication; in fact, an ideal opportunity to repair an umbilical hernia is at the completion of the TUBA. We have done that on numerous occasions; however, it does increase the postoperative pain.

Navel rings are no impediment to the TUBA procedure, as the incision is simply detoured behind the jewelry hole. Some surgeons prefer to leave such navel jewelry in place during the procedure, even using it as a retractor, whereas our preference is to have it removed a few days in advance rather than work around it. The device can be sterilized and reinserted after the completion of the procedure if the patient so desires (7); as an alternative, a polypropylene suture loop can be placed to use as a retractor and to later keep the jewelry track from closing. The TUBA procedure also combines quite well with other simultaneous procedures, such as abdominoplasty, liposuction, or tubal ligation. Two of our patients had a unilateral TUBA procedure done at the time of postmastectomy reconstruction of the opposite side, both patients having felt strongly that they did not want any scar on their remaining breast. As mentioned earlier, another disqualification for TUBA is the choice of prefilled saline or silicone implants, and it is questionable whether the shaped implants are suitable for the TUBA method due to an increased possibility of rotation. We did use textured, round implants in two patients early in our TUBA experience, but because textured, round implants have not been proven to have any long-term advantage over smooth ones, we no longer use them for any breast augmentations.

Planning

Because the transumbilical breast augmentation does not lend itself to trying various sizes of implants intraoperatively, size determination is done in advance, using any of the customary methods. Our preference for doing so is the use of adjustable volumetric sizers within the patient’s chosen bra size, in conjunction with a dimensional approach with particular attention to the transverse diameter of the breast and the thickness by pinch test at the top of the breast and at the inframammary fold (23). It should be kept in mind that because the TUBA procedure permits insertion of larger sizes of implant without fear of dehiscence, the surgeon must accurately assess the patient’s tissue characteristics in order to fully discuss with her the consequences and trade-offs that her desired size may involve; this is often a very lengthy discussion (24). Our philosophy is to permit the patient to make her own choices, which of course places upon us the responsibility of educating her about the trade-offs involved in all those choices (25).

Accordingly, the decision of whether to place the implants in front of or behind the pectoralis muscle must also be made in advance, and since May 19, 1999, when the senior author started doing the subpectoral TUBA technique, he has given patients who request the incision in the navel their choice of placement plane. Since the date when both procedures were offered, about 60% have chosen prepectoral placement and 40% have chosen subpectoral placement. A full discussion of the pros and cons of prepectoral versus subpectoral placement is beyond the scope of this chapter, other than to point out two very important aspects: first, that the incidence of capsular contracture in our practice has been the same for prepectoral and subpectoral implants, provided that prepectoral patients do daily compression (not displacement) massage; second, that

just as studies have shown that implanted women are not more likely to get breast cancer than those without implants (26), there has never been any reported difference in the accuracy of mammographic breast cancer detection, nor any difference in prognosis, between prepectoral and subpectoral augmentation (27), theoretical mammographic considerations notwithstanding. Having said that, it should be pointed out that some radiologists find it faster to read mammographic films of subpectoral implants than prepectoral ones, and other the contrary.

just as studies have shown that implanted women are not more likely to get breast cancer than those without implants (26), there has never been any reported difference in the accuracy of mammographic breast cancer detection, nor any difference in prognosis, between prepectoral and subpectoral augmentation (27), theoretical mammographic considerations notwithstanding. Having said that, it should be pointed out that some radiologists find it faster to read mammographic films of subpectoral implants than prepectoral ones, and other the contrary.

On rare occasion, for patients with great asymmetry, we have recommended that on one side the implant be placed prepectoral and on the other side subpectoral. As no convincing evidence has ever been presented showing any advantage to subfascial or subserratus/rectus augmentation, we have not attempted either via the navel but speculate that either might be somewhat challenging to perform via the navel.

In our practice, several separate informed-consent documents are used. These include the general augmentation consent; an “off-label consent” for any endoscopic procedure (transumbilical or transaxillary); a consent for the drawbacks of implants of greater than 400-cc volume; and an “optimal fill consent” for bringing the implant volume to its optimal value even if that volume exceeds the manufacturer’s specified maximum for that implant (28), resulting in “overfill.” We prefer to have these documents understood and signed well in advance of the operation; therefore they are completed in the office, giving the patient an opportunity to address any areas of concern with the surgeon or the office nurse.

Patient Preparation

We advise patients to exercise preoperatively to strengthen the abdominal muscles. All medications that inhibit coagulation, including vitamin E and herbal remedies, are discontinued 2 weeks prior to the procedure. As is our practice for any operation done under general anesthesia, to help prevent postoperative constipation, it is a kindness to patients to have them empty the gastrointestinal tract preoperatively with stool softeners and laxatives. Patients are instructed to do meticulous cleansing of the navel with antimicrobial soap the day before the operation. Any navel jewelry must be removed 2 days before operation.

On the operative day, an intravenous antibiotic is administered. Prior to any sedation being given, the patient is visited in the holding area and prepares her skin with alcohol, including cotton-tipped applicators inside the navel. With the patient standing, the markings are then done: first the midline is drawn from sternal notch to xiphoid, and then the existing inframammary creases. A second semicircular line is then drawn below the breasts, using as the radius from the anticipated breast center the sum of the radius of the implant plus the thickness of the lower breast tissues as determined by the pinch test. The vertical pocket limits are also indicated on each upper breast. To indicate the paths of the tunnels, on each side a line is drawn from the umbilicus toward the medial edge of the areola for prepectoral procedure or toward the head of the pectoral muscle for subpectoral procedure. As has been discussed in the literature (29), often the navel is not in the midline; this can have medicolegal consequences, so it is worthwhile pointing that out to the patient preoperatively, along with any other asymmetries.

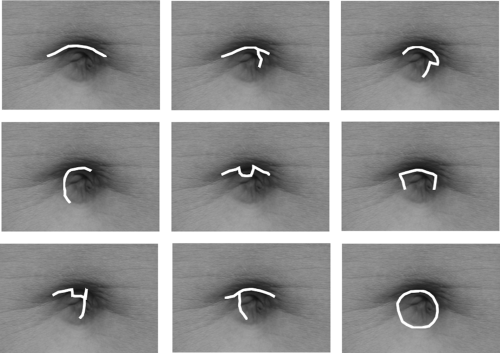

To best ensure that the incision scar is well hidden within the navel, that too should be drawn with the patient standing. A variety of configurations can be used (Fig. 114.3), whichever is best hidden entirely within the specific contours of the patient’s navel, as long as the incision has sufficient length to comfortably allow insertion of the Johnson tube with no resistance. As a rough guide, the incision length, when stretched, should equal one half of the circumference of the Johnson tube. For the 19-mm diameter tube this is usually on the order of about 2 cm total length before stretching of the incision. We have not yet encountered a navel too small to allow an adequate incision to be completely hidden within it.

Implant Preparation

The implants and the expanders are inspected and prepared on a separate back table before the patient is under anesthesia, thereby providing the opportunity to cancel the procedure in the unlikely event of finding faulty devices. It is important to check the imprinted markings on the implants, as it has happened that a correctly marked box actually contained the wrong implant. Rather than filling with saline and watching for fluid leaking, testing the implants by watching for air bubbles when they are immersed in saline is a far superior method, with the caveat that no additional (potentially unsterile) room air is ever added. We use fresh, powder-free gloves whenever handling the implants. It is a noteworthy reflection upon the manufacturer’s acceptance of the transumbilical technique that Allergan supplies extra-long fill tubes in the implant boxes, and Mentor now makes long fill tubes available. (The long fill tubes can be ordered separately: Mentor #600975-002 and Allergan #2955-02). Shorter fill tubes would require a sterile extension tube; if desired, a silk tie can be used to secure the tubing junction, but a tight twist fit suffices. Using a completely closed system, about 50 mL of saline is instilled into each implant to permit removal of all the air. A closed system greatly reduces the possibility of introducing pathogens into the implant and will likely become the standard of care, if not an FDA requirement. The implant is rolled as the remaining saline is removed, allowing the implant to hold its rolled-up shape as it traverses the slippery subcutaneous tunnel, and in fact the implant usually maintains its orientation without difficulty. Both the implants and the expanders are rolled in the same manner, like a scroll from side to side inward to protect the fill tube (Fig. 114.4) rather than in a cigar shape as described in the original article, to assist in maintaining orientation while transversing the tunnel. The expanders are prepared in a similar manner, again verifying the size marks on the devices, immersion testing for leaks, instilling a small amount of saline, and rolling them up during saline withdrawal. Because expanders are supplied with long tubing, they do not require extensions, but they do require a silk tie to secure their connector to the fill tube, as the hydraulic pressures involved in pocket creation can cause the locking connector to pop off of the fill tube. After preparation, the implants are returned to their sterile containers.

Operative Technique

The operating room setup is fairly standard (30); a right-hand-dominant surgeon will likely prefer to stand on the patient’s

right side with the monitor near the patient’s left shoulder. The operating table is preheated with warm air. As soon as the patient arrives in the operating room, a cotton ball soaked in iodophor is placed in the navel and left there until the prep. The patient is positioned supine with arms at 90 deg for prepectoral or 70 deg for subpectoral procedure. The knees are kept flat, no pillow or other object behind them, to avoid obstructing the instruments. We favor use of a warming blanket and pneumatic stockings. Sedation and local can be used for the TUBA, but with the excellent agents now available, we prefer general anesthesia for all breast augmentations. The laryngeal mask (LMA) is ideal for both prepectoral and subpectoral TUBA. We prefer that nitrous oxide not be used for operations such as TUBA, abdominal liposuction, or abdominoplasty because it can cause abdominal distension. Monitoring includes pulse oximetry, blood pressure, electrocardiogram, and often a bispectral index neurologic monitor. Muscle relaxation should not be present during initial tunnel formation in order to keep the rectus muscles taut and flat. Later, for subpectoral augmentation only, a short-acting relaxant can be given after the obturator has reached the inframammary crease.

right side with the monitor near the patient’s left shoulder. The operating table is preheated with warm air. As soon as the patient arrives in the operating room, a cotton ball soaked in iodophor is placed in the navel and left there until the prep. The patient is positioned supine with arms at 90 deg for prepectoral or 70 deg for subpectoral procedure. The knees are kept flat, no pillow or other object behind them, to avoid obstructing the instruments. We favor use of a warming blanket and pneumatic stockings. Sedation and local can be used for the TUBA, but with the excellent agents now available, we prefer general anesthesia for all breast augmentations. The laryngeal mask (LMA) is ideal for both prepectoral and subpectoral TUBA. We prefer that nitrous oxide not be used for operations such as TUBA, abdominal liposuction, or abdominoplasty because it can cause abdominal distension. Monitoring includes pulse oximetry, blood pressure, electrocardiogram, and often a bispectral index neurologic monitor. Muscle relaxation should not be present during initial tunnel formation in order to keep the rectus muscles taut and flat. Later, for subpectoral augmentation only, a short-acting relaxant can be given after the obturator has reached the inframammary crease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree