The lower lid-cheek junction and the nasolabial folds are probably the two major stigmata of the aged face. Over the past two decades the use of the transtemporal approach has gained wide popularity to rejuvenate the midface and the lower eyelid-cheek junction. Primarily due to its reliable and reproducible results and limitation of the morbidity related to the open approaches. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy is of paramount importance to safely release all the fascial attachments while avoiding injuries to the facial nerve. The authors discuss their surgical technique in detail, the post-operative care and possible complications.

Key points

- •

The transtemporal midface lift allows for a volumetric remodeling of the cheek, improves the double contour over the lower lid-cheek junction enhancing its support, improves the nasolabial fold and jowl areas, and allows for simultaneous resurfacing of the skin.

- •

Dissection involves transitioning from the deep layer of the deep temporalis fascia to the subperiosteal plane overlying the forehead, zygoma, and maxilla.

- •

The location of the frontal branch of the facial nerve can be closely estimated by the identification of the sentinel vein that travels from the temporoparietal fascia to the deep temporal fascia.

- •

The eyebrow position can be maintained or elevated during the procedure, and a lower blepharoplasty is always performed to better redrape the lower eyelid.

- •

The lateral canthal distortion and chemosis that sometimes occurs following the procedure is transitory, and its position returns to normal in a few weeks postoperatively.

Overview

Facial harmony, which is an essential component of an aesthetically pleasing face, is gradually lost as a result of aging. This dissonance is often dramatically reflected in the upper two-thirds of the face with the development of forehead rhytids, lateral sagging of the eyebrows with hooding of the upper eyelids, vertical elongation of the lower eyelids, cheek descent with exposure of the infraorbital rim, creation of the double convexity irregularity, and deepening of the nasolabial fold. The lower lid-cheek junction and the nasolabial folds are probably the two major stigmata of the aged face. This stigmata is further exemplified by illustrators that create those contours in a portrait when they want to transform a youthful face into an older one.

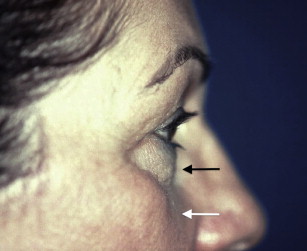

The lower lid-cheek junction has been defined as a line that extends laterally from the midpupillary line running parallel to the inferior orbital rim, slightly inferior to it. The medial extension of this line is commonly referred as the tear trough ( Fig. 1 ). The effacement of the lower lid-cheek junction is a very powerful way of rejuvenating a face. This effacement can be accomplished in a wide variety of ways that range from simple in-office injection of fillers to the more complex transtemporal midface lift.

Overview

Facial harmony, which is an essential component of an aesthetically pleasing face, is gradually lost as a result of aging. This dissonance is often dramatically reflected in the upper two-thirds of the face with the development of forehead rhytids, lateral sagging of the eyebrows with hooding of the upper eyelids, vertical elongation of the lower eyelids, cheek descent with exposure of the infraorbital rim, creation of the double convexity irregularity, and deepening of the nasolabial fold. The lower lid-cheek junction and the nasolabial folds are probably the two major stigmata of the aged face. This stigmata is further exemplified by illustrators that create those contours in a portrait when they want to transform a youthful face into an older one.

The lower lid-cheek junction has been defined as a line that extends laterally from the midpupillary line running parallel to the inferior orbital rim, slightly inferior to it. The medial extension of this line is commonly referred as the tear trough ( Fig. 1 ). The effacement of the lower lid-cheek junction is a very powerful way of rejuvenating a face. This effacement can be accomplished in a wide variety of ways that range from simple in-office injection of fillers to the more complex transtemporal midface lift.

Anatomy

It was demonstrated that the anatomy of the lid-cheek junction and the tear trough were intimately related in a cadaver study. The investigators demonstrated that these junctions between the lower lid and the cheek correspond to differences in the skin, subcutaneous plane, and suborbicularis plane. The skin thickness changes significantly from the extremely thin eyelid skin to a thicker cheek skin. Moreover, the lower eyelid skin sits directly over the orbicularis oculi, whereas the cheek skin is separate from it by the malar fat pad. This fat pad is a triangular thickening of the subcutaneous fat in the cheek area overlying the maxilla that lies superficial to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) and will provide most of the volume of the midface.

In the subcutaneous plane, the lid-cheek junction corresponds to the transition from the palpebral to the orbital portions of the orbicularis oculi. Deep to the muscle, there is a difference in how it attaches to the orbital rim and maxilla. Medially, corresponding to the tear trough, the muscle is firmly attached to the bone, without a dissection plane. Laterally, starting at a point between the medial limbus and the midpupillary line, the muscle has its bony attachment through the orbicularis retaining ligament. This area is where the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) is found. This adipose tissue is much smaller than the malar fat pad, but its elevation or increase in volume can significantly improve results in midface rejuvenation. SOOF has been described as 2 distinct fat pads: a medial compartment that extends form the medial limbus to the lateral canthus and a lateral component that extends from the lateral canthus to the temporal fat pad.

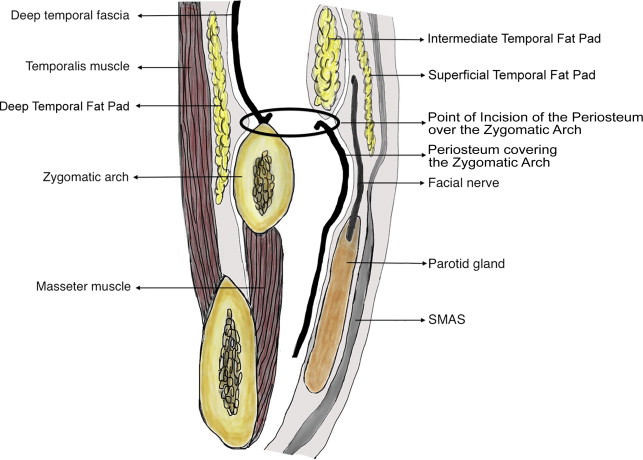

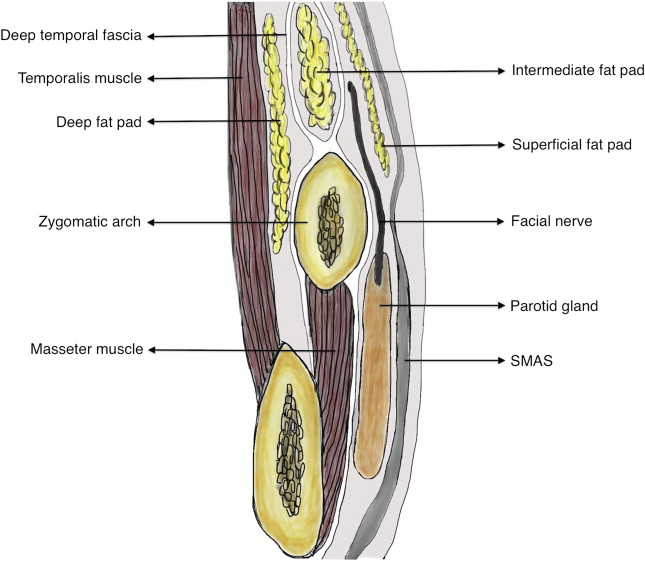

In terms of surgical anatomy pertaining specifically to the transtemporal approach, the surgeon needs to be familiar with the fascial planes overlying the temporalis muscle and zygomatic arch and its relationship to the frontal branch of the facial nerve. The most superficial layer is referred as the superficial temporal fascia , or temporoparietal fascia (TPF), which is the direct extension of the SMAS above the zygomatic arch. Superiorly, it will be contiguous to the galea of the scalp. Its importance lies in the fact that the frontal branch and the superficial temporal vessels lie within this fascial layer. Deep to the TPF lies the deep temporal fascia, which is divided into a superficial and a deep layer. The superficial layer attaches in the lateral aspect of the zygomatic arch, whereas the deep layer attaches in the medial aspect. Between these 2 layers, the intermediate temporal fat pad is found. Deep to the deep layer is the deep temporal fat pad ( Fig. 2 ).

The facial nerve travels deep to the musculature and innervates them for their undersurface. The midface muscles are innervated by the buccal and zygomatic branches, which are protected with the subperiosteal dissection. However, the anatomy of the temporal branch becomes critical. This branch (or branches, because there are usually more than one) exits the parotid gland and crosses the zygomatic arch approximately in its middle third. The most commonly used surface landmark for the course of the facial nerve, known as Pitanguy line , is a line that runs from 0.5 cm inferior to the tragus to 1.5 cm above the lateral eyebrow. However, because the eyebrow is a somewhat imprecise landmark, a more consistent approximation is the line that begins at the inferior aspect of the ear lobe and bisects another line connecting the superior border of the tragus to the lateral canthus ( Fig. 3 ).

Nevertheless, a more accurate means to precisely identify the location of the temporal branch of the facial nerve was described by Sabini and colleagues. A series of bridging veins that correspond to the location of the frontal branch travel from the TPF to the deep temporal fascia and can be seen during the endoscopic dissection. One in particular, the sentinel vein, is larger than the others and is usually located 1 cm from the frontozygomatic suture line ( Fig. 4 ). This vessel has been reported to be within a 0- to 10-mm radius of the nerve.

Evaluation

Careful patient selection is perhaps the most important factor for a successful transtemporal approach. Crucial components of preoperative evaluation include lower eyelid position, degree of orbital rim exposure and length of the lid-cheek junction, presence of lower lid fat pseudoherniation, volume of SOOF and malar fat pads, and the depth of the nasolabial folds. The precise diagnosis of which midfacial changes are responsible for the aged look will dictate the most appropriate procedure to be performed.

A considerable portion of the evaluation should be focused on the lid-cheek junction. Its length and the presence of the double contour deformity of the lower lid should be assessed because these are the 2 features that will be most significantly impacted by the midface elevation ( Fig. 5 ).

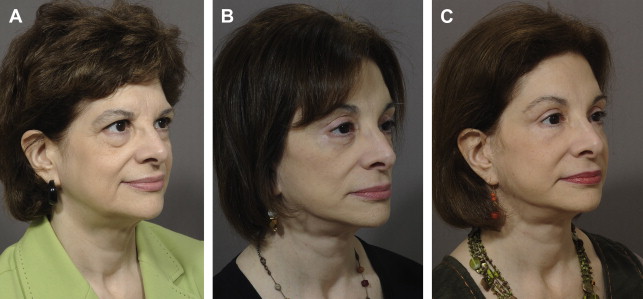

An improvement in the patients’ appearance with a finger elevation of the malar fat complex will give the surgeon and the patients an estimate of what can be achieved surgically. Proper assessment of the patients’ absolute volume loss cannot be overemphasized. The authors frequently see that the patients that would benefit the most from a midface lift are the same patients who have the most severe loss of facial volume. It is important to bring this issue into discussion and point out that patients may require soft tissue augmentation in addition to the midface lift ( Fig. 6 ).

Patient perspective

Preoperative patient education is imperative. It reduces anxiety and establishes realistic goals. Patients should understand what the procedure is attempting to achieve, which areas are going to be improved, and the limitations. The need for complementary approaches, such as volume augmentation and skin resurfacing, should be discussed preoperatively. The patients’ ability to take time for recovery should also be included in the discussion. Although volume augmentation with fillers has essentially no downtime, techniques with subperiosteal dissection may include a longer period of postoperative edema of up to 4 to 6 weeks.

A discussion of patients’ existing brow asymmetries preoperatively is critical to avoid patient dissatisfaction postoperatively. Another consideration is the presence of preexisting upper eyelid ptosis. This condition can be unmasked with successful elevation of the brows. Again, patient education preoperatively as to the possible effect of a brow lift on the appearance of their lid ptosis is a must.

Transtemporal midface lifting

Inspired by the work of Hinderer and colleagues, Tessier, and Psillakis and colleagues that described a subperiosteal dissection for facial rejuvenation, the midface started to be approached in a subperiosteal plane with incisions in the temporal and forehead areas in the early 1990s. This technique provides a volumetric remodeling of the cheek, corrects the deepening of the lower lid-cheek junction enhancing its support, improves the nasolabial fold and jowl areas, and allows for simultaneous resurfacing of the skin. It also allows for a simultaneous temporal and forehead lift, which prevents bunching in the temporal and malar areas and rejuvenates the midface in conjunction with the upper third of the face leading to a more harmonious result.

Technique

Presurgical marking

- •

Patients are examined preoperatively in the upright position, and surgical markings are then performed to delineate anatomic landmarks and incisions.

- •

The temporal line is marked after manually palpating the temporalis muscle contraction as the patients clench their teeth.

- •

The temporal incision starts approximately 1 cm behind the hairline at the superior aspect of the temporalis muscle, and it continues for 3 cm inferolaterally. Care must be taken that this incision is 1.5 to 2.0 cm inferior to the superior temporal line or suspension sutures placed into the deep temporal fascia will be difficult to place.

- •

The medial incisions for brow suspension are marked a few millimeters behind the hairline centered over the lateral canthus and extend posteriorly for 2 cm.

- •

The Pitanguy line, corresponding to the course of the frontal branch of the facial nerve as described earlier, is also drawn out.

- •

Finally, markings are placed at the supraorbital notches. These marks are made bilaterally.

- •

Eyebrow assessment is also performed at this time; the decision to maintain, elevate, or lower the brow is made. Although the medial brow position is typically maintained, resection of the procerus and corrugator muscles, primary brow depressors, reduces the chance of postoperative brow depression, which enables the treatment of horizontal forehead rhytids with botulinum toxin without risking further brow ptosis.

- •

In most patients with mild to moderate brow ptosis, 2 to 4 mm of brow elevation is required to bring the medial aspect of the brow to the level of the supraorbital rim. The authors avoid excessive elevation of the medial brow, as this leads to an unnatural appearance leaving patients with a surprised look.

Incision and dissection

- •

The temporal incision is carried down through the superficial temporal fascia to the deep temporal fascia.

Surgical note: When making the incision, the surgeon has to bevel the scalpel parallel to the hair follicles to achieve maximal scar camouflage, as transecting the hair follicles results in a few millimeters of permanent alopecia .

- •

A double hook is used to retract the skin superiorly, and a blunt dissector (Ramirez EndoForehead “T” Dissector No. 4, Snowden Pencer, Tucker, GA) is used to elevate the superficial temporal fascia and overlying tissue off the deep temporal fascia to the temporal line.

- •

The dissector is gently pushed against the deep fascia at a 30° to 45° angle to achieve the proper plane.

- •

The dissection continues superiorly in a subperiosteal plane after dissection through the tenacious fascia of the temporal line and ends at the level of the occiput. This technique ensures that the elevated forehead and lateral temporal tissues will redrape and not bunch anteriorly once suspended.

- •

At this point, the dissection proceeds anteriorly.

- •

A fiber-optic lighted Aufricht retractor is used to optimize visualization as the dissection proceeds to release the fascial attachments of the temporal line and the subperiosteal dissection proceeds along the supraorbital rim.

- •

Laterally, the conjoint tendon is dissected bluntly. If this fascial condensation is not released adequately, elevation of the lateral brow will be incomplete during suspension.

- •

The arcus marginalis can often be released from its lateral end to within 1 cm of the superficial marking made for the supraorbital neurovascular bundle using a curved dissector (Ramirez EndoForehead Arcus Marginalis Dissector No. 6, Snowden Pencer, Tucker, GA).

- •

Bimanual dissection is often helpful, and the hand placed on the surface of the skin helps prevent injury to the orbit with inferior dissection.

- •

The medial incision is then made down to the frontal bone. This technique allows exact measurement of the amount of brow elevation from the preoperative brow position. The suspension translates into the amount of medial brow elevation, as the forehead flap between the 2 medial incisions moves as a sheet superiorly and translates primarily to the midbrow and medial brow.

- •

The remaining subperiosteal dissection of the forehead pocket is performed to within 1 cm of the supraorbital notch. This blind elevation extends medial to the bundle, over the glabella, and onto the radix of the nose.

- •

The endoscope is then passed through the medial incision, and the supraorbital neurovascular bundle is dissected subperiosteally under direct visualization.

- •

The arcus marginalis and conjoint tendon release is completed under endoscopic visualization with a curved dissector (Ramirez EndoForehead Periosteal Spreader No. 7, Snowden Pencer, Tucker, GA).

- •

The corrugator supercilii and procerus muscles are resected and cauterized; this will eliminate the vertical and horizontal glabellar furrow.

- •

If brow asymmetries are present preoperatively, unilateral orbicularis oculi myotomies may be performed.

- •

Following complete elevation of the forehead and superior orbital rim, the dissection proceeds inferiorly.

- •

Inferior temporal dissection is initially performed blindly for 2 to 3 cm, at which point the lighted Aufrecht retractor is again used to optimize visualization and put some tension over the fascial planes that will facilitate the elevation.

Surgical note: With inferior temporal dissection, the surgeon must take extra care in the region of the Pitanguy line. As described earlier, multiple bridging veins that penetrate the plane of dissection perpendicularly in the region of the frontal branch of the facial nerve are encountered during this dissection. As mentioned earlier, a cadaveric study has demonstrated these veins to be within 2 mm of the frontal branch . It is important to preserve these vessels whenever possible in order to prevent engorgement of the temple veins postoperatively .

- •

If cautery is necessary, the veins are freed 360° and put on tension. The bipolar cautery is applied to the deep aspect of the vessel at the deep temporal fascia. These steps prevent conduction of heat superficially toward the frontal branch.

Surgical note: An additional measure of caution is necessary in the temporal region because forceful dissection may result in penetration through the deep temporal fascia. Penetration through this layer will expose the infratemporal fat pad, and even minimal trauma can result in reduction of its volume with temporal wasting postoperatively .

- •

Further inferior dissection approaches the zygomatic arch.

- •

At the level of the deep temporal fascia split, the intermediate temporal fat is encountered, being safe to dissect within this fat pad.

Surgical note: The authors prefer to elevate the intermediate fat pad up and dissect on top of the deep temporal fascia. The authors think that elevating all of these tissues helps provide an additional cuff of tissue to insulate the frontal branch from thermal or mechanical trauma .

- •

A lateral 1-cm cuff of tissue is preserved at the lateral canthus to prevent permanent distortion postoperatively.

- •

The periosteum over the entire superior aspect of the zygomatic arch is exposed, and it is incised at the anterior aspect of the arch.

- •

The EndoForehead Arcus Marginalis Dissector No. 6 is used to release the periosteum over the anterior face of the zygomatic arch. The zygomaticofacial foramen often is encountered and the neurovascular structures kept intact, if possible, as this is an important landmark for later suspension of the midface.

- •

Subperiosteal dissection continues posteriorly at the superior edge of the zygomatic arch to within 1 cm of the external auditory canal.

- •

Once the edge is exposed, the periosteum over the zygomatic arch is released.

- •

This subperiosteal dissection is continued medially over the infraorbital rim to the nose in a blind fashion.

- •

Bimanual dissection is required with the dissector passed between the index finger that protects the globe and the thumb positioned over the infraorbital nerve.

- •

The periosteal dissector is then passed inferiorly starting at the body of the zygoma directed toward the pyriform aperture, inferior to the infraorbital nerve. This technique accomplishes dissection over the anterior wall of the maxilla and, with a superior sweeping motion, releases all tissue inferior to the infraorbital nerve. Care should be taken here not to direct the dissector through the buccal mucosa.

- •

Subsequently, the tendinous attachments at the lateral aspect of the maxilla are lysed with the EndoForehead Arcus Marginalis Dissector; the masseteric tendon just inferior to the inferior aspect of the zygomatic arch is cut with a downward motion.

- •

The flap is dissected inferiorly below the masseteric aponeurosis just on top of the belly of the masseter to approximately 1 cm superior to the gonial angle ( Fig. 7 ).