Topical Immunomodulators: Introduction

Topical immunomodulators are nonsteroidal agents that target the immune system for therapeutic effect in the skin. The macrolactams, pimecrolimus and tacrolimus, act as anti-inflammatory agents by binding immunophilin and inhibiting cytokine production. The imidazoquinoline amine, imiquimod, induces interferon (IFN) production and enhances immune responses, although several more potent analogs are under clinical investigation.

Mechanism of Action

|

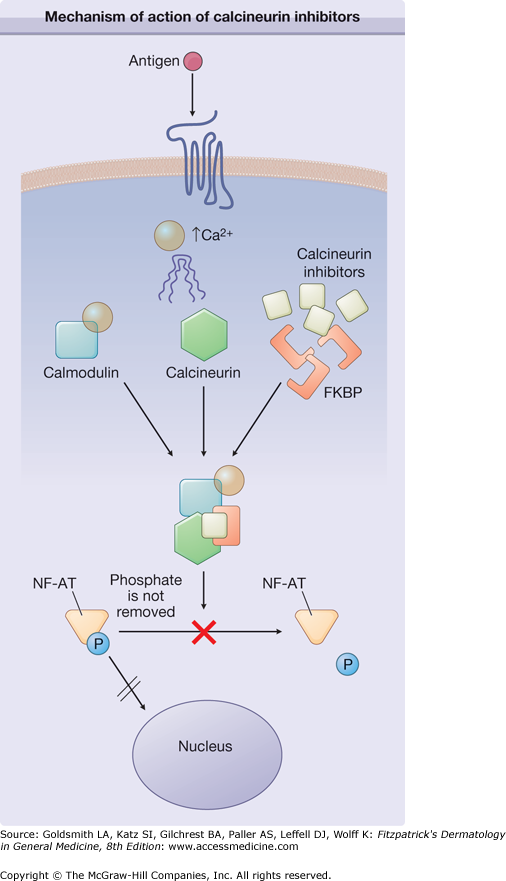

Intracellular signaling pathways are tightly controlled to maintain immune homeostasis. The nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors has emerged as a central regulator in immune signaling pathways that control lymphocyte activation and cytokine production.1 In the absence of receptor-mediated, calcium-dependent signaling, NFAT is sequestered in the cytoplasmic compartment in an inactive, phosphorylated state (Fig. 221-1). Signaling pathways emanating from antigen receptors induce calcium-dependent activation of calcineurin, which removes the phosphorylation from NFAT that leads to nuclear translocation and upregulation of proinflammatory gene expression. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus turn off inflammation by interacting with FK-506 binding protein (FKBP). This drug-protein interaction prevents calcineurin from dephosphorylating NFAT, thereby inhibiting its nuclear translocation.2 The pleiotropic effects of calcineurin inhibitors include decreased T-cell proliferation and reduced inflammatory cytokine production of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-3, IL-4, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor, and IFN-γ.

Compared to cyclosporine, tacrolimus is 10–100 times more potent, has lower molecular weight, and penetrates the skin better. These enhanced pharmacological properties of tacrolimus provided a basis for experiments demonstrating topical inhibition of contact hypersensitivity and subsequent development as an ointment for treating atopic dermatitis.3,4 With topical tacrolimus therapy, more than 70% of patients have had moderate-to-excellent improvement in 3-week controlled trials, and 30%–40% have had greater than 90% improvement.5 In general, response to topical tacrolimus has been best observed in treating thinner skin areas such as the face and neck. During remissions, dosing may be reduced in frequency, but flares occur with discontinuance. Response is slow (over days to weeks), often incomplete on extremities (especially hands and feet), and in patients with lichenified lesions. Roughly 25% of patients, especially those with the most severe disease, do not have a satisfactory therapeutic response. Additionally, patients should realize that exacerbations of atopic dermatitis may occur and require occasional intervention with topical or systemic corticosteroid therapy. The main advantage of topical tacrolimus is the provision of chronic maintenance therapy without the need for continuous topical corticosteroids. Koo et al demonstrated up to 91% reduction in affected body surface area in a study of nearly 8,000 adults and children using topical tacrolimus for up to 18 months without significant adverse events.6 Other long-term studies with tacrolimus have specifically shown no evidence of cutaneous atrophy, little or no increased infectious risk other than a slightly increased rate of herpes simplex virus in some trials, hypertension, renal toxicity, or cumulative blood levels in patients older than 2 years of age.7

Adverse effects have been primarily an intense burning and itching in 30%–40% of patients at application sites, especially in areas of flaring, excoriation, and erosion.5,7,8 These symptoms usually subside in a few days, in concert with healing of the skin. However, some patients continue to have bothersome burning, and this effect seems to be more prominent when the skin is exposed to heat such as during summer weather, or in baths or hot tubs. In general, these problems with burning sensations seem to be less in children. Up to 10% of adults experience symptoms of flushing with alcohol ingestion.9 Both acneiform and rosaceiform eruptions have been observed in conjunction with tacrolimus and pimecrolimus use and should be monitored.10–12 Other common side effects include flu-like symptoms and headache.3

Infections have not been a notable problem in tacrolimus-treated patients.3,5,7 Occasional staphylococcal skin infections occur, but they are no worse than before treatment, and studies actually demonstrate a reduction in Staphylococcus aureus colonization during prolonged therapy. In spite of the theoretical concern about immunosuppression, there have been no significant increases in frequency or severity of warts, varicella, or molluscum contagiosum infections. Some cases of eczema herpeticum have been noted in clinical trials, but the risk of this complication may also stem from underlying atopic dermatitis.

Immunosuppression with systemic calcineurin inhibitors is known to raise the relative risk of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder and ultraviolet light-induced cutaneous carcinomas in transplant patients, which carries theoretical concern for malignancy with long-term use of topical formulation of the same agents. A smattering of postmarketing reports of lymphoma or malignancy in patients using topical tacrolimus and a biologically plausible risk related to TCI use were the major factors in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) calling for a black-box warning label. Recently, a case-control study evaluated the association between topical immunosuppressants and lymphoma in a cohort of patients with atopic dermatitis and found no increased risk of lymphoma with the use of TCIs.13 Extensive review of the case reports by independent oncologists and allied task forces has not found evidence of an increased risk of lymphoma or other malignancy.14–16 However, predisposition to malignancy may require several years of constant immunosuppression. Therefore, close surveillance is indicated if TCIs are used chronically.

In addition to the concerns about hematologic malignancy, there have been reports of pigmented neoplasms in association with TCI use. In a case series of three patients, focal pigmented lesions developed where TCIs were used that were confirmed histologically to represent lentigines.17 Similarly in our experience, lentigines have arisen at the location of TCI use. The implication of these cases is whether chronic TCI use predisposes to melanoma. There has been a case report of rapid growth of melanoma develop in a child during the course of treating vitiligo with topical tacrolimus.18 Although this remains an isolated case report, it would be prudent to counsel patients to use sun protection while using TCIs. Furthermore, the utility of self-surveillance of changing moles and thorough clinical skin examination should be discussed when using TCIs.

Pimecrolimus has a similar structure to tacrolimus and interacts with the same FKBP to inhibit calcineurin activation of NFAT.19 However, clinical efficacy is less than that of tacrolimus as reflected by decreased protein-binding affinity, which necessitates a higher drug concentration in the topical medication.7 Topical pimecrolimus also appears to have little systemic immunosuppressive effect, which may reflect a wider margin of safety. Clinical trials have included infants as young as 3 months of age, although FDA approval has been limited to 2 years of age and older. A recent study of 76 infants and children revealed sustained benefit without significant adverse effect with pimecrolimus therapy for 2 years.20 Two patients in the study developed eczema herpeticum. As with tacrolimus, occasional postmarketing reports of lymphoma and malignancy moved the FDA to affix the black-box warning label to the entire class of medication, but these concerns remain at present theoretical.16 Blood levels have been detected in occasional patients, but no high or prolonged levels have been detected. Initial studies of oral pimecrolimus were promising, but, in the wake of the black-box controversy, development has been suspended.

|

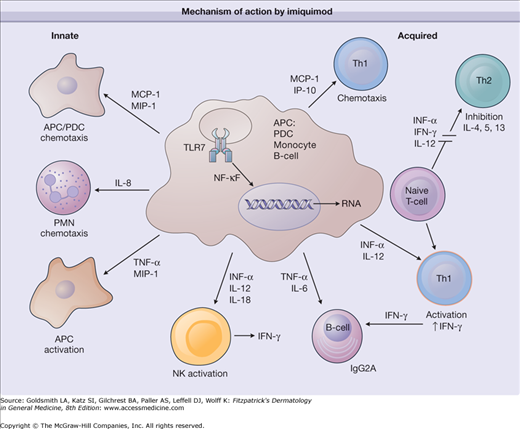

Imiquimod is unique in that it appears to enhance both acquired and innate immune function (Fig. 221-2). Topically applied imiquimod induces local cytokine production from keratinocytes and other cells.21,22 Imiquimod acts as an agonist of the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-7 and -8-mediated signaling cascades, resulting in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-α and IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor, and the chemokines IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, and monocyte chemotactic protein 1.23,24 Imiquimod also stimulates the innate immune response by increasing natural killer cell activity, activating macrophages and Langerhans cells, and inducing proliferation and maturation of B lymphocytes. Additionally, imiquimod has direct proapoptotic activity on tumor cells.

Figure 221-2

Mechanism of action by imiquimod. APC = antigen-presenting cell; IFN = interferon; IgG2A = immunoglobulin G2A; IL = interleukin; IP-10 = interferon-inducible protein 10; MCP-1 = macrophage chemoattractant protein 1; MIP = macrophage inflammatory protein; NF-κB = nuclear factor κB; NK = natural killer cell; PDC = peripheral dendritic cell; PMN = polymorphonuclear neutrophil; Th = T helper; TLR = Toll-like receptor; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α.

Imiquimod has been shown to be an effective treatment for anogenital warts. A 16-week study of 311 immunocompetent adults with external anogenital warts compared three times weekly 5% imiquimod cream, 1% imiquimod cream, and placebo.25 Clearance was achieved in more than 70% of women and 30% of men with the 5% cream and with both strengths significantly better than placebo. Response rates greater than 30% have been seen in uncircumcised males treated under the foreskin, suggesting that increased moisture may account for this gender discrepancy. Similarly, local factors may account for lower response rates in nongenital warts. The primary benefit of imiquimod cream relative to other available wart therapies is ease of administration. In adults, home therapy for genital warts is preferred, given the sensitive nature of this problem. Likewise in children, genital warts may be a result of sexual abuse (although in the minority of younger children), and an atraumatic topical therapy that can be rapidly applied in a nonthreatening environment is ideal. Recurrence rates following use of imiquimod cream have ranged from 13%–19%.25

In vitro evidence of antitumor effects formed the basis for evaluation of imiquimod in the treatment of cutaneous neoplasms. A multicenter, randomized, open-label dose-response trial showed an almost 90% histologic clearance rate of superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) when 5% imiquimod cream was applied daily for 6 weeks. Twice daily application led to an improved response rate but a higher incidence of local skin reactions.26 Geisse et al subsequently reported that two phase III double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled trials showed histologic clearance of 82% with five times weekly treatment.27 Daily therapy was no more effective, and response was positively correlated with signs of inflammation, including erythema, erosion, and crusting. These studies formed the foundation for using imiquimod to treat small, superficial BCC in low-risk locations such as the trunk and extremities. These are anatomical sites that may tolerate the lower cure rates better than more cosmetically sensitive areas.23 The use of imiquimod as monotherapy in this context was endorsed by a recent systematic review.28

Imiquimod has also been approved as a treatment for actinic keratosis of the head and neck. Hadley et al recently reviewed the use of imiquimod for actinic keratoses. In five randomized controlled trials lasting 12–16 weeks involving 1,293 patients, complete clinical clearance was seen in 50% of imiquimod patients versus 5% using vehicle. Adverse events were significantly higher in imiquimod-treated groups, including erythema (27%), crusting/scabbing (21%), flaking (9%), erosion (6%), edema (4%), and weeping (3%).29 Lower potency imiquimod preparations (2.5, 3.75%) are currently under development for the treatment of head and neck AKs. These compounds theoretically permit increased frequency of use without prohibitive application site reaction, while also allowing a greater surface area to be treated. Early safety and efficacy trials are promising.30

Although not yet clinically indicated as an antiangiogenic agent, imiquimod has demonstrated antiangiogenic properties in vitro and in a series of case reports. The antiangiogenic properties of imiquimod stem from the production of antiangiogenic cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-12; the upregulation of endogenous antiangiogenic mediators, including tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase; and downregulation of the proangiogenic factors, basic fibroblast growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinase 9.31 In a mouse model of hemangioendothelioma, imiquimod application resulted in fewer and smaller tumors.32 Numerous clinical reports have noted clinical response treating vascular neoplasms, including hemangiomas of infancy and pyogenic granulomas.33–36 Ongoing clinical trials are further defining the role of imiquimod in the treatment of various vascular lesions.37

Derived from its antiviral effects, imiquimod has been used successfully to treat molluscum contagiosum. In an observer-blinded, randomized trial of 74 children, imiquimod resulted in slower clearance with higher expense, but was tolerated with less pain and improved cosmesis when compared to liquid nitrogen.38 There have been few cases in which imiquimod was effective in treating granuloma annulare when used for 6–12 weeks.39,40 Whether the efficacy is the result of proapoptotic effects of imiquimod remains to be determined. While not intended to be exhaustive, other published off-label uses of imiquimod include treating extramammary Paget disease, scar cosmesis, low-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasms, dysplastic nevi, lentigo maligna, ecthyma contagiosum, porokeratoses, and lymphomatoid papulosis.41–47 These off-label uses of imiquimod await confirmation and precise dosing recommendation from randomized clinical trials.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree