13 Thumb reconstruction

Nonmicrosurgical techniques

Synopsis

Thumb reconstruction should aim to restore the cardinal thumb actions: mobility, stability, sensibility, length, and appearance.

Thumb reconstruction should aim to restore the cardinal thumb actions: mobility, stability, sensibility, length, and appearance.

Level of thumb loss is divided into thirds: distal (tip to interphalangeal joint), middle (interphalangeal joint to metacarpal neck), and proximal (metacarpal neck to carpometacarpal joint).

Level of thumb loss is divided into thirds: distal (tip to interphalangeal joint), middle (interphalangeal joint to metacarpal neck), and proximal (metacarpal neck to carpometacarpal joint).

Distal third reconstruction typically requires only soft-tissue restoration.

Distal third reconstruction typically requires only soft-tissue restoration.

Numerous options exist for middle-third reconstruction, including increasing thumb ray length (metacarpal lengthening, osteoplastic reconstruction) and increasing relative length (phalangization).

Numerous options exist for middle-third reconstruction, including increasing thumb ray length (metacarpal lengthening, osteoplastic reconstruction) and increasing relative length (phalangization).

Proximal third reconstruction is best accomplished with pollicization or on-top plasty (pollicization of a damaged index finger). However, microsurgical reconstruction (discussed in another chapter) is preferred at this level.

Proximal third reconstruction is best accomplished with pollicization or on-top plasty (pollicization of a damaged index finger). However, microsurgical reconstruction (discussed in another chapter) is preferred at this level.

Introduction

• When thumb loss occurs due to trauma, replantation is the best method of reconstruction for many patients. When replantation is not possible, thumb reconstruction is warranted.

• The level of thumb amputation guides the type of reconstruction. Determination of level of loss is based on physical examination and radiographs.

• Any thumb reconstruction method requires input and acceptance by the patient. The reconstruction should be tailored to the patient’s personal and professional needs. Because significant rehabilitation may be required, the patient must be a willing participant in both the reconstruction and rehabilitation.

• Functional compensation following distal-third thumb loss is easily achieved, therefore, reconstruction at this level is chiefly soft tissue alone. Techniques such as the neurovascular advancement (Moberg) flap and the cross-finger flap remain reliable methods for reconstruction at this level.

• For losses in the middle third of the thumb, restoration of length is a priority. This can be done via absolute length restoration with metacarpal lengthening or osteoplastic reconstruction, or via relative length restoration using phalangization of the thumb.

• Proximal third thumb losses are best treated with microsurgical reconstruction. However, in some cases this may not be possible. In these situations, transfer of another finger can provide an excellent thumb replacement. A normal finger (typically the index) can be pollicized to become a thumb. A damaged index finger can also be transferred (on-top plasty) to become a stable post for opposition, pinch, and grip.

• Hand rehabilitation after reconstruction is absolutely necessary, especially following middle- and proximal-third reconstructions. Rehabilitation can last months, but allows the patient to regain motion and strength. For some procedures, such as neurovascular island flaps and digit transfer, sensory re-education is an important part of the rehabilitation.

• This chapter will provide a comprehensive description of nonmicrosurgical thumb reconstruction, including reconstruction decision-making, technical approaches, and postreconstruction management.

Historical perspective

Littler extensively reviewed the history of thumb reconstruction, a field in which he has been a major contributor.1 Nicoladoni introduced two techniques, namely, osteoplastic reconstruction and toe transfer through the pedicle method.2 Guermonprez was among the first to pollicize a finger, a technique subsequently refined by the island principle, attributed to Littler and Gosset.3–7 A mobile and sensate thumb was obtained, but at the price of sacrificing a finger. Matev originated the technique of progressive lengthening through distraction, maintaining good sensibility and improving length.8,9 A major advance was the introduction of microvascular techniques, which led to microvascular free toe-to-hand transfer. First- and second-toe transfers were initially described, followed by refined techniques allowing the surgeon to improve the appearance of the reconstructed thumb while at the same time minimizing donor site morbidity.

Basic science/disease process

Other insults that can result in thumb loss requiring reconstruction are infections and neoplasms. Because tumors are less acute than trauma or infections, thumb reconstruction planning can be more deliberate, and can even be performed at the time of tumor extirpation.10

Patient selection

Many thumb injuries occur in the workplace, and these patients will be affected by the injury because their work involves significant hand use. In these patients especially, it is essential to work toward a thumb that has adequate length for both gripping and pinching, is stable during activities, has reasonable motion, and, importantly, is sensate in order to give tactile feedback during these actions and to prevent recurrent ulceration or injury. That said, adequate length, stability, motion, and sensibility are the end-goals for any patient requiring thumb reconstruction, regardless of profession or vocation.11

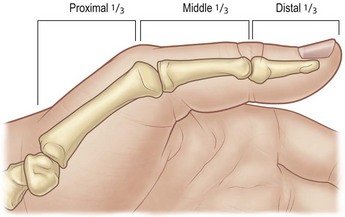

The most important factor in patient selection is the amount and nature of tissue loss that must be reconstructed. The level of amputation is the easiest way to classify thumb deficiencies, and is listed in thirds12 (Fig. 13.1). The distal third extends from the interphalangeal joint to the thumb tip. The middle third is the portion between interphalangeal joint and the metacarpal neck, and the proximal third is from metacarpal neck to the carpometacarpal joint. Each amputation level presents unique challenges for patient and physician, and each level can be reconstructed with multiple modalities.

Treatment/surgical technique

Distal third

Thumb distal-third amputations rarely, if ever, require restoration of length, as a thumb amputated through the interphalangeal joint remains very functional.12 Therefore, the chief goals of thumb tip reconstruction are soft-tissue coverage of bone and length preservation. When there is no bone exposed at the tip of the thumb, closure can be achieved with either healing by secondary intention or skin grafting. Secondary healing of tip amputations has been shown to result in a stable scar and good two-point discrimination, and is therefore a relatively easy (and usually the preferred) method of achieving coverage.13 Secondary healing by wound contracture has the advantage of bringing stable, sensate skin together to close the defect, as opposed to skin grafts, which remain insensate. Defects up to 1.5 cm in diameter with no bone exposure can be effectively treated with dressing changes. Daily dressing changes with petroleum or bismuth-impregnated gauze are relatively easy for patients. Larger defects with a stable base, however, require skin grafting. Full-thickness grafts are usually preferred, as they are more durable and stable, especially in the contact areas subject to pressure and shear. Small full- or split-thickness skin grafts can be harvested from the hypothenar eminence or the volar wrist crease. Larger skin grafts, however, are best harvested from the groin crease.

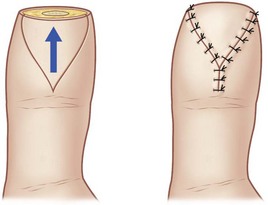

When phalangeal bone is exposed at the thumb tip, vascularized coverage is required to preserve length, and there are several flaps that can accomplish these goals. The main criteria for flap selection are defect size and location of soft-tissue loss, specifically if it is volar, dorsal, or at the tip. The V-Y advancement flap described by Atasoy et al. provides good coverage of the tip of the distal phalanx when only a very small amount of bone is exposed14 (Fig. 13.2). The technique involves incising the volar pulp of the thumb in a V shape. Scissors are then used to spread the subcutaneous tissue carefully. The subcutaneous attachments deep to the flap, which provide the neurovascular supply to the flap, are left intact. The flap is then advanced distally to close the defect and the proximal aspect of the V is closed side to side, thereby creating the Y shape of the final scar. In practice, there is limited application for this flap due to the limited advancement that is possible without devascularizing the flap.

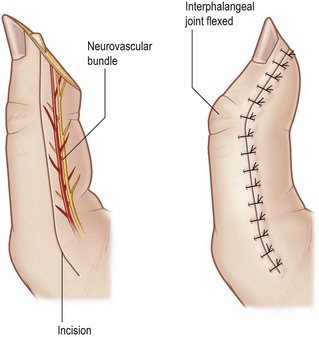

The neurovascular volar advancement flap, which goes by the eponym of the Moberg flap, is well suited to cover volar and tip defects of the thumb.11 It is often described as an advancement flap, but in reality, the amount of advancement achieved with the conventional rectangular Moberg flap is limited. Instead, the elevation of the flap allows flexion of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb, thereby allowing the flap to appear to “advance” distally (Fig. 13.3). To elevate the flap, one incises the mid-lateral lines on either side of the thumb, down to the base of the proximal phalanx. The flap is then elevated from the deeper tissues, directly off the flexor retinaculum, with sharp dissection. The flap includes both neurovascular bundles and all of the subcutaneous tissue down to the flexor tendon sheath. The interphalangeal joint is flexed, and the flap is inset at the tip. If necessary, a Kirschner wire can be placed across the interphalangeal joint to stabilize it, though this is seldom required. This flap can easily cover a defect of 1–2 cm2 (Fig. 13.4). A variation of the Moberg flap is an island flap in which flap is incised transversely across the proximal base, and the only remaining attachments are the two neurovascular bundles. Unlike the conventional Moberg flap, this method will allow a small amount of actual advancement, thereby covering more distal defects. The proximal gap at the base of the flap will then require a small skin graft.

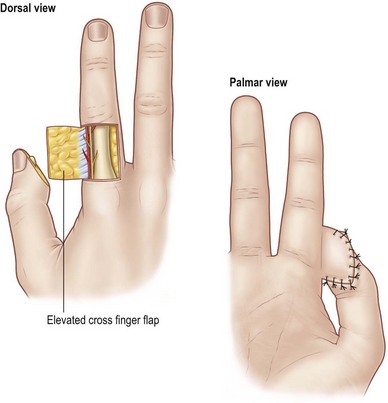

The cross-finger flap from the index finger is an excellent reconstructive technique for larger volar and tip defects of the thumb, up to 2–3 cm2.15 The tissue transferred is reliable and durable.16 The chief disadvantages to this technique are thumb coaptation to the index finger for 2–3 weeks, and the need for a skin graft on the index donor site. A radially based rectangular flap is marked on the dorsum of the index proximal phalanx that extends from the ulnar to the radial mid-lateral lines (Fig. 13.5). The flap is incised and elevated from ulnar to radial in the plane between the subcutaneous tissues and the extensor mechanism. It is critically important to leave the paratenon on the extensor to allow skin grafting. Upon reaching the radial aspect of the flap, one must release Cleland’s ligaments along the length of the base of the flap to prevent kinking at the flap “hinge.” The flap is then sutured to the thumb – this may require some trial and error to find the best flap orientation (Fig. 13.6). A full-thickness skin graft is then sutured to the dorsum of the index finger. A bulky thumb splint is applied. At 2 or 3 weeks, the flap is divided and the inset to the thumb is completed (Fig. 13.7). After division, aggressive range-of-motion therapy for both the thumb and index finger should begin.

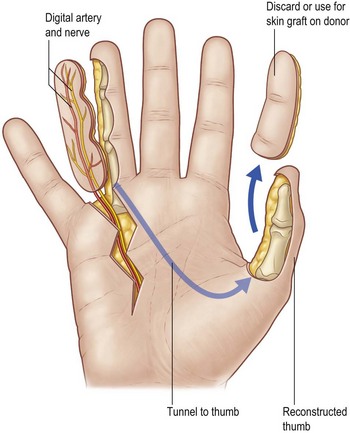

The neurovascular island flap attributed to Littler is a valuable tool in thumb reconstruction.17 It is rarely used as a primary coverage flap, although it is certainly possible to use it in that manner. Rather, its most common use is for the restoration of sensation to the thumb pulp following reconstruction.17,18 The flap is based on the ulnar neurovascular bundle of either the middle or ring finger (Fig. 13.8). The ulnar side of the digit is chosen because its loss will have minimal effect on grip and pinch activities. The dimensions of the flap needed are marked on the ulnar pulp of the chosen donor finger. Often, the flap will require harvesting of skin over the distal and middle phalanges of the donor finger. The flap is incised, and a mid-lateral incision proceeding from the proximal aspect of the flap is made. The flap is elevated from distal to proximal, and the entire ulnar neurovascular bundle is elevated in continuity with the flap. It is critical to raise the neurovascular bundle with a fairly thick cuff of surrounding fatty tissue containing the vasa vasorum of the artery, as that is the only source of venous outflow for the flap. Failure to do this will result in flap congestion. One must dissect fairly proximally in the palm to allow adequate transposition to the thumb, and the other branch of the common digital artery (i.e., the radial digital artery to the ring or small finger) must be divided. The common digital nerve can be split along the fascicles to allow adequate flap mobility. The flap can then be transposed to the thumb either via subcutaneous tunnel, or a connecting incision from the donor site to the thumb can be made (Fig. 13.9). The flap is then inset into the volar defect of the thumb. The donor site is grafted with full-thickness skin. In addition to postoperative restoration of motion, patients must work with a hand therapist on sensory re-education of the thumb.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree