Numerous solutions for post-blepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction are reviewed. Patients require permanent recruitment of skin and soft tissue to lengthen the lower eyelid and control of the lower eyelid shape. The authors use a hand-carved expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) implant held with microscrews to provide volume and felting material at the orbital rim and to permanently fix vertically lifted cheek soft tissue into the lower eyelid. The eyelid margin is also controlled with a hard palate graft inset into the conjunctival surface below the tarsus. This eyelid reconstruction avoids tension on the lateral canthoplasty, a point of failure in other solutions.

Key points

- •

Post-blepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction is caused by transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty.

- •

The muscular hammock of the lower eyelid is prone to injury.

- •

Orbital rim projection plays a critical role in post-blepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction and its correction.

- •

Skin grafts are aesthetically unacceptable and should be avoided.

- •

The best restoration results combine soft tissue advancement with autogenous grafts and alloplastic implants.

Video content accompanies this article at http://www.facialplastic.theclinics.com

Introduction

This article surveys the post-blepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction (PBLER) literature and presents the authors’ personal approach. Early investigators characterized PBLER as ectropion, , which implies the eyelid margin rotates outward off the eye surface. This is a less common post-blepharoplasty finding than a vertically short eyelid that conforms to the eye surface. After surgery, scarring in the planes of the eyelid, weakening of the lower eyelid orbicularis oculi muscle, and deficiencies of soft tissue contribute to lower eyelid malposition. Lack of projection of the inferior orbital rim contributes to a so-called negative vector lower eyelid. These changes are often lumped together as lateral scleral show, or mischaracterized as ectropion. , , Corneal exposure with dry eye symptoms is common, including foreign body sensation, contact lens intolerance, red eyes, excessive tearing, and, in more extreme cases, impairment of vision, photophobia, corneal breakdown, and ulceration.

Anatomy

The lower eyelid is suspended by the lateral and medial canthal ligaments that insert into the orbit rim. The eyelids comprise a specialized muscular sphincter externally covered by a keratinized epithelium and internally lined by the palpebral conjunctival epithelium, a nonkeratinized squamous epithelial over a substantia propria firmly adherent to the tarsus. The lined surfaces of the eyelid glide over the bulbar conjunctiva and cornea with lubrication provided by mucin from conjunctival goblet cells and tear aqueous produced by lacrimal glands. The tarsus conforms to the eye surface, allowing the eyelid margins to act as a wiper for the cornea moving the tear film. Compared with the upper eyelid, the shape and position of the lower eyelids are influenced significantly by tension in the canthal tendons.

In the youthful face, a cushion of subcutaneous fat extends over the lateral orbital rim and zygoma, creating subtle separation between the orbital and temple aesthetic units. Medially, the nasojugal fold, or tear trough, represents the location where the inferior orbital orbicularis oculi muscle inserts medially onto the maxilla. Laterally, the palpebral-malar groove, or lid-cheek junction, is formed by the orbitomalar ligament, also called the orbicularis retaining ligament, and lateral orbital thickening. ,

A solid body of work suggests branches of the facial nerve, supplying the orbicularis oculi muscle at the eyelid margin, approach perpendicularly and are at risk from an infracilliary skin/muscle incision. , A study by Choi and colleagues seems to refute this, suggesting that the lateral orbicularis over the tarsus is innervated by motor nerve branches that arise medially and extend horizontally from the so-called medial orbicularis motor line. Hwang has noted atonic eyelids are more common laterally. Additional research is needed to resolve this controversy.

Pathophysiology

Investigators have sought to localize the injury that accounts for PBLER. Shorr and Goldberg described lid shortening from scarring in any of the eyelid planes: skin and orbicularis (anterior lamella), orbital septum (middle lamella) or conjunctiva and lower eyelid retractors (posterior lamella). Other investigators similarly, attribute PBLER to scarring in any of these planes.

Schwarcz and colleagues investigated scarring of the middle lamella in PBLER. The investigators compared transconjunctival blepharoplasties performed in the postseptal versus the preseptal plane. This study confirms that transconjunctival lower eyelid surgery, whether preseptal or postseptal, is not associated with lower eyelid retraction. The scarring involved in transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty affects multiple layers due to direct tissue disruption and a motor nerve injury that compromises the hammock function of the lower eyelid. The surgical dissection planes inevitably are organized by dense scar tissue after transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty.

Nonsurgical methods

Hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers have been used to relive PBLER. Goldberg and colleagues reported on HA filler to treat lower eyelid retraction in 31 patients. The etiologies included thyroid-related orbitopathy (8/31), postsurgical (trauma repair, post-blepharoplasty, and postcancer reconstruction) (19/31), and involutional (4/31). The average case was treated with 0.9 mL per eyelid. Overall, there was a 1.04-mm reduction in inferior scleral show with treatment. Treatment effects diminished 50% over an average of 4.6 months. Complications were minor, including bruising, swelling, and contour irregularities.

Xi and colleagues presented a retrospective review of 27 cases of lower eyelid retraction,including 14 post-blepharoplasty and 13 non-cosmetic cases managed with HA filler. They reported 96.3% (26/27) cases that they describe as complete improvement of the retraction with no reoccurrence in 9 months of follow-up. The investigators invoked the generalized form of Hooke’s law and the effect of increasing the bulk modulus of the lower eyelid with the HA filler to explain their results.

The point made by Xi and colleagues is that infiltrating a lower eyelid with HA filler increases the bulk modulus of the lower eyelid, effectively stiffening it. Under the right circumstances, injecting filler into the eyelid improves its resistance to stress and strain. The result can be an improvement in PBLER. The concept of altering the bulk modulus of the lower eyelid as the basis for improving lower eyelid retraction suggests that higher G-prime fillers should be favored over low G-prime fillers, a finding consistent with clinical experience.

Surgical methods

In 1969, Tenzel described surgery for lower eyelid lagophthalmos. His repair mobilized the lateral canthal tendon from the orbital rim. The lower eyelid was de-epithelialized, and the skeletonized lower eyelid lateral tendon was accommodated into a small incision made through the exposed upper eyelid lateral canthal retinaculum and sutured in place. Anderson and Grody described the “lateral tarsal strip.” It consisted of a lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis. They split the gray line into anterior and posterior lamella, as needed. The conjunctival epithelium then was denuded to make the strip and resuspended to the orbital rim.

In 1985, Shorr and Fallor reported the Madame Butterfly repair for PBLER. Their goal was functional improvement in eyelid closure and position without a skin graft. Surgery included a lateral canthotomy, cantholysis, and lateral cheek undermining. If this did not permit the eyelid to elevate, residual resistance was attributed to a midlamellar scar. An en glove lysis of the scar was performed followed by lateral canthal resuspension. The lateral cheek was resuspended to the periosteum lateral to the orbital rim. They placed the lateral canthus 4 mm above the medial canthus. Postoperatively, the lateral canthus relaxed to a more neutral position.

Baylis and colleagues described a series of 30 patients with PBLER. They found scarring and contraction of the plane of the orbital septum the most common cause of retraction. Patients were managed with lateral canthotomy and en glove lysis of the scar tissue and retractors at the inferior boarder of the lower eyelid tarsus. The lower eyelid was placed on traction to the eyebrow postoperatively. When a spacer graft was needed, ear cartilage was utilized. It was inserted into the dissection tract, avoiding the need for an infracillary or transconjunctival incision. Eyelid contour irregularities due to distortion of the ear cartilage required revision in 4 of 13 cases. Their series had a very high rate of surgical revision: 58% of cases involving only scar and retraction lysis and 21% of cases when a spacer graft was used.

Siegel described the use of hard palate grafts (HPGs) for eyelid reconstruction in 1985. He used HPG in 11 patients as a liner material in eyelid reconstruction. Subsequently, Kersten and colleagues used HPG in managing lower eyelid retraction in 18 patients. Cohen and Shorr also used HPG as part of lower eyelid retraction repair including 9 of 18 patients with PBLER in conjunction with the Madame Butterfly procedure. HPG was associated with minimal shrinkage with healing. Oral discomfort was described as acceptable and resolved in 7 days to 10 days.

Barmettler and Heo found no statistical difference in the use of autologous ear cartilage, bovine acellular dermal matrix, and porcine acellular dermal matrix for the repair of lower eyelid retraction. MacIntosh and colleagues studied failed cartilaginous grafts. Explanted auricular graft was enclosed by a peudoperichondial membrane. Kerfing used to improve graft flexible also left the auricular grafts susceptible to fragmentation and cracking.

Oh and colleagues reported a series of 13 patients with PBLER addressed with a drill-hole canthoplasty and suborbicularis oculi fat suspension. The periosteum at the orbital rim was elevated to expose the bone and a drill hole was made 2 mm above the desired height of the lateral canthal angle. Polypropylene suture (4-0) resuspended the lateral canthal tendon to the hole. A dissection in the preperiosteal plane was used to mobilized suborbicularis oculi fat that was sutured to the drill hole. All patients were reported satisfied with their surgical results with relief of dry eye symptoms.

Taban described lower eyelid retractor recession without the use of an internal spacer graft for PBLER. He excluded eyelids with midlamellar scarring, which he felt warranted a spacer graft. Success was based on subjective patient satisfaction, which was described as high with the exception of one cased described to be over corrected. This work highlights that spacer grafts are not needed in every case. A position consistent with Griffin and colleagues.

Brock and colleagues used autogenous dermis grafts for as a posterior eyelid spacer in 7 patients with PBLER. All eyelids demonstrated improved lower eyelid position and the patients reported improved symptoms. Other investigators have been less successful with this approach. Yoon and McCulley reported a 30% complication rate in their series. Patel and colleagues repaired lower eyelid retraction using HPG, midface lift, and lateral canthoplasty in 17 patients. They performed a preperiosteal midface lift via an upper or lower eyelid incision. They claimed complete correction of inferior scleral show in all cases with no major complications. However, 1 of their patients developed an oral palatal fistula.

Ben Simon and colleagues reported a 5-year series of subperiosteal midface lifts with or without the use of a HPG to address lower eyelid retraction in 34 patients. They performed lateral canthotomy and cantholysis followed by a transconjunctival incision. A subperiosteal midface lift with inferior periosteotomy was performed. The mobilized midface then was sutured in multiple locations to the inferior orbital rim. Frost sutures were placed completing surgery when no midlamellar spacer was used. In total, 21% of their patients had mild residual eyelid retraction and 1 patient needed revisional surgery.

Dailey and colleagues reported lower eyelid retraction repair with porcine dermal matrix (ENDURAGen, Stryker CMF, Newman, Georgia) as a spacer graft in 100 consecutive patients (160 eyelids). Complications (15% of patients) included implant exposure or rejection, irritation, inflammation, cyst formation, implant kinking, and eye pain. The implant was removed in 9 eyelids. Cosmetic results were reported as very acceptable. Grumbine and colleagues also reported the use of acellular porcine dermal collagen matrix. Two of their patients were revised due to implant complications.

Taban and colleagues reported on their use of “thick” acellular human dermis (AlloDerm, Allergan, Dublin, Ireland) in a consecutive series of patients presenting with lower eyelid retraction. They reported 16 of 21 eyelids had improved lower eyelid position. Five surgeries were characterized as failures. The investigators suggest that their results were comparable to HPG and that thick acellular dermis was better than thin acellular human dermis, but they did not present data to support the later conclusion.

A porous polyethylene (Medpor, Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan) lower eyelid spacer was introduced for the repair of lower eyelid retraction. An early series using the implant was promising with a low revision and complication rate. Tan and colleagues found that complications, minor (26% [9/35]), and major (23% [8/35]) were common and required surgical intervention. These investigators concluded the implant should be reserved for cases where other methods have failed. Mavrikakis and colleagues presented 4 cases of failed porous polyethylene lower eyelid spacers requiring explantation.

Yoo and colleagues studied 5-fluorouracil with or without triamcinolone to modify postoperative healing of skin grafts in a series of 19 patients presenting with lower eyelid retraction. Patients were reported to be very satisfied with the surgical outcome and the appearance of the graft in 17 of 19 cases. The surgeon rated the eyelids as excellent in 18 of 19 cases.

McAlister and Oestreicher reported that it was possible to repeat posterior lamellar grafting in cases where the initial effort was not sufficient. Most patients had a second posterior lamellar graft of hard palate mucosa (42/46 eyelids [91%]). A second procedure further reduced residual inferior scleral show, demonstrating a role for secondary posterior lamellar grafting.

Pascali and colleagues reported a retrospective, 10-year study of lower eyelid retraction repair. They performed an infracillary incision, subperiosteal midface with lower eyelid tarsal resuspension via an upper eyelid incision anchored to a drill hole at the orbital rim. Goldberg noted this series reinforced the concept that vertically lifting the cheek recruits needed soft tissue and skin into these compromised eyelids. Park and colleagues investigated the best graft material for reconstructing lower eyelid retraction. Many of these cases involve the use of a spacer graft combined with lateral canthoplasty, lateral tarsal strip, and midface lifting procedures. No graft material was found superior to others. The use of HPG was associated with more donor site and eyelid complications compared with other graft materials.

Galindo-Ferreiro and colleagues surveyed Spanish and Brazilian oculoplastic surgeons regarding lower eyelid retraction. Respondents diagnosed lower eyelid retraction 62% of the time based on inferior scleral show and 23.5% of the time based on a limitation of lower eyelid excursion to the lower limbus. Surgeons often performed lower eyelid retraction surgery after waiting 6 or more months (54%), but correction also was performed commonly at 3 months or earlier (41.8%). Management included lateral canthoplasty, spacer graft, lower eyelid retractor recession, and cheek-lift. Among autogenous spacer grafts, auricular cartilage was most common (39.2%), followed by HPG (22.7%), and tarso-conjunctival graft (19.6%). Lower eyelid retractors were released in 84.7% of cases versus retractor dissection and excision (15.3%). In cases involving a midface lift, a preperiosteal lift was preferred (58.3%) versus subperiosteal lift (41.6%).

The vertical midface lift

Senior author (KDS) has developed and refined a powerful and versatile method for PBLER using a vertical midface lift method. One aspect missing from all of the methods, discussed previously, is the absence of a flexible method to augment the orbital rim to help provide support for the lower eyelid. These eyelids are commonly vertically short of soft tissue in all planes, including skin. There typically is a motor injury to the muscular hammock function of the lower eyelid margin. Scarring effectively tethers the lower eyelid to the cheek. Some investigators use a drill hole placed in the lateral orbital wall in order to permanently suture recruited skin and cheek soft tissue into the lower eyelid. Although such methods do augment missing skin and soft tissue in the eyelid, they do little to correct the projection of the cheek along the lower orbital rim, which often is the fundamental reason for lower eyelid soft tissue deficiency. This is recognized as the basis for the negative vector lower eyelid. The approach developed by the senior author (KDS) uses a hand-carved expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) orbital rim implant to both augment the orbital rim projection and also function as a felting material so that vertically lifted cheek soft tissue can be permanently fixed to the orbital rim. This allows the lifted cheek to permanently contribute skin and soft tissue volume to the lower eyelid. An HPG also is used in these reconstructions to control the shape of the lower eyelid contour. Readers are referred to the surgical video that accompanies this article to supplement the description that follows (Video 1).

Prior to surgery, the patient is sent to a dentist for a clear acrylic stent to cover the hard palate for use after the graft is harvested. The stent has retention at the base of the teeth and initially assists to control bleeding after harvesting the graft. After surgery it protects the donor site and contributes to postoperative comfort.

Surgery is performed under intravenous sedation so the patient can cooperate during surgery. General anesthesia precludes this cooperation. During surgery, the patient is sat up to judge the placement of the reconstructed lateral canthal angle. It is beneficial to immobilize the eyelids on Frost sutures after surgery for a week. Patients do not tolerate having both eyes patched simultaneously. For that reason, bilateral surgery is staged. The Frost sutures are removed on postoperative day 6 and the second side is performed as early as the next day. One side of the hard palate is anesthetized where the graft will be harvested. The lower eyelid, cheek to the gingival sulcus, and soft tissue to the zygomatic arch and temporal fossa also are anesthetized.

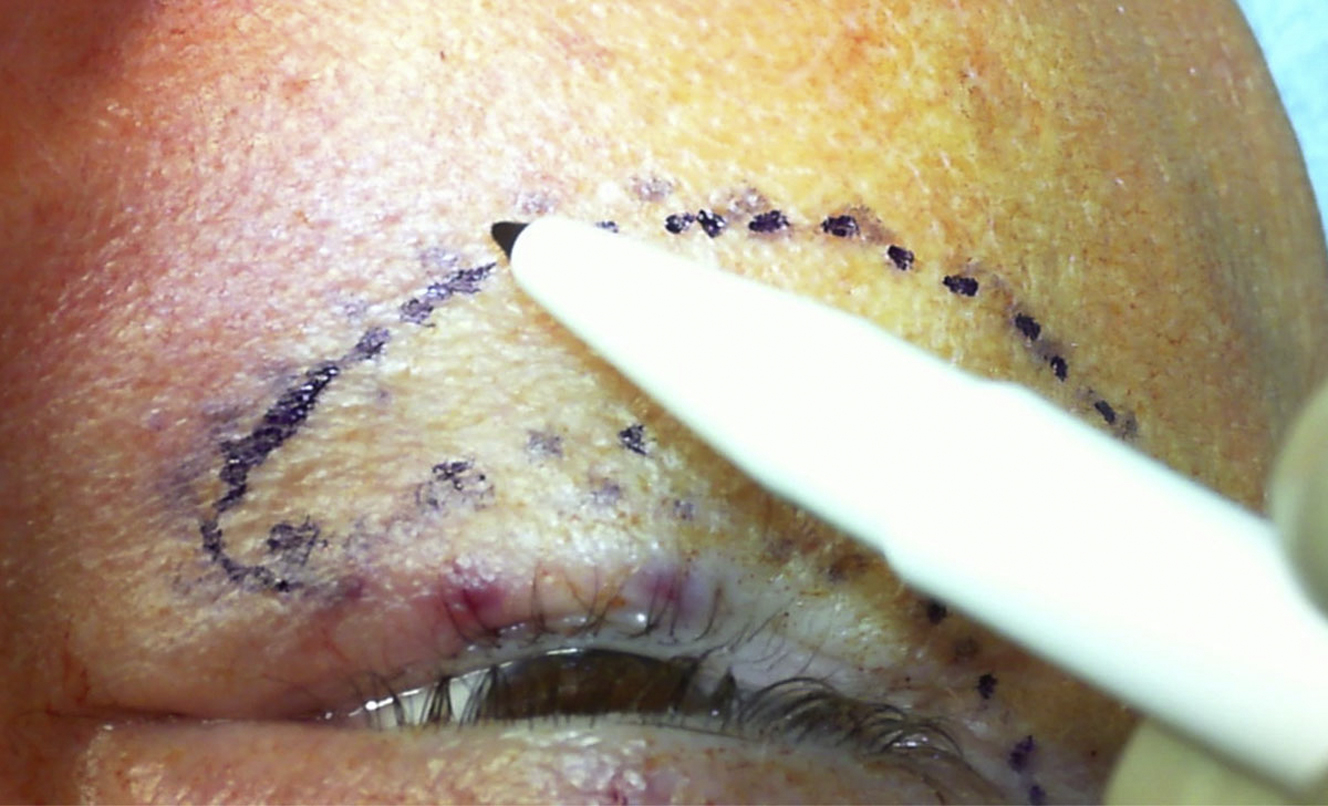

A methylene blue marking pen and a cotton tip applicator are used to outline a template to fabricate an ePTFE rim implant ( Fig. 1 ). These markings are transferred to sterile paper and then to a block of carveable ePTFE measuring 3 cm × 7 cm × 5 mm (Surgiform, Surgiform Technology, Lugoff, South Carolina) ( Fig. 2 ). The implant is carved on a nylon board with a series of #10 and #11 blades to desired shape and thickness. Caution and experience are needed to best judge implant size and thickness. As a rule, smaller implants are better accepted than over-sized implants. Commonly the finished implant may be only 2.5 mm in thickness along the orbital rim and rapidly taper to the edges with overall dimensions of 6 cm by 3 cm ( Fig. 3 ). It is soaked in a solution of gentamycin (80 mg in 100 mL of injectable saline) for use later in the case.