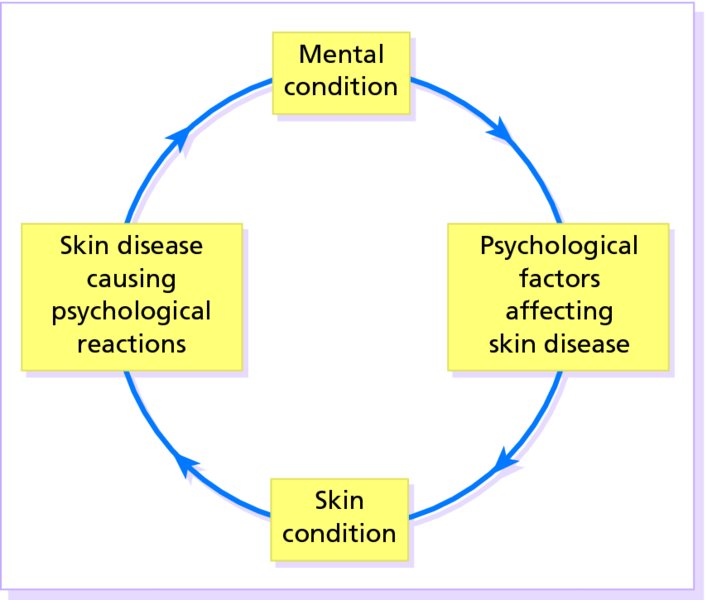

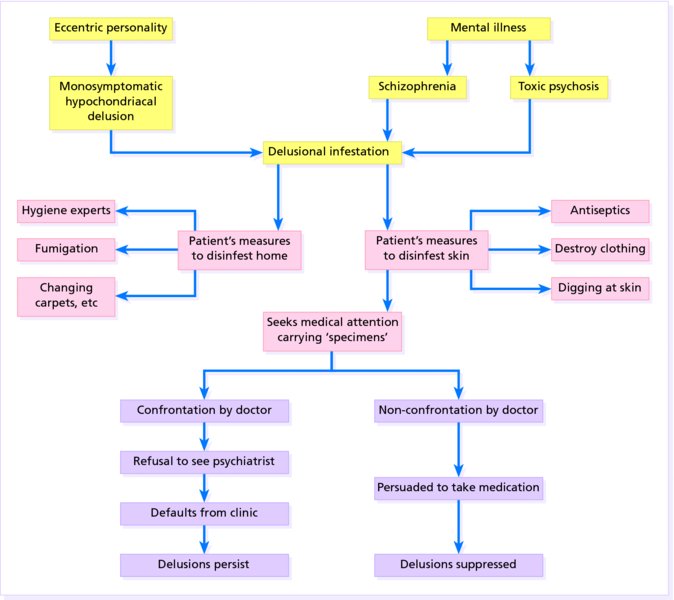

23 Most people accept that there are strong links between the skin and the emotions. Embarrassment causes blushing; anxiety causes cold, sweaty palms; anger causes the face to redden, but only a few skin disorders, such as dermatitis artefacta, have emotional factors as their direct cause. The relationships between the mind and the skin are usually subtle and complex. Nevertheless, patients with skin disorders do have a higher prevalence of psychiatric abnormalities than the general population, although specific personality profiles and disorders can seldom be tied to specific skin diseases. Similarly, it is still not clear how, or even how often, psychological factors trigger, worsen or perpetuate such everyday problems as atopic eczema or psoriasis. Each school of psychiatry has its own theories on the subject, but their explanations do not satisfy everyone. Do people really damage their skin to satisfy guilt feelings? Does their skin ‘weep’ because they have themselves suppressed weeping? Until more is known, it may be wise to adopt a simpler and more pragmatic approach, in which interactions between the skin and psyche are divided into two broad groups: Figure 23.1 Mind–skin interactions. The presence of disfiguring skin lesions can distort the emotional development of a child: some become withdrawn, others become aggressive, but many adjust well. The range of reactions to skin disease is therefore wide. At one end lies indifference to grossly disfiguring lesions and, at the other, lies an obsession with skin that is quite normal. Between these extremes are reactions ranging from natural anxiety over ugly skin lesions to disproportionate worry over minor blemishes. A chronic skin disease such as psoriasis can undoubtedly spoil the lives of those affected. It can interfere with work, and with social activities of all sorts including sexual relationships, causing patients to feel like outcasts. Studies have shown that a diagnosis of psoriasis has a negative impact on quality of life equivalent to that of other major medical diseases such as cancer, diabetes and depression. The heavy drinking of so many men with severe psoriasis is one result of these pressures. An experienced dermatologist will be on the lookout for depression and the risk of suicide, as up to 10% of patients with psoriasis have had suicidal thoughts. However, these reactions do not necessarily correlate with the extent and severity of the eruption as judged by an outside observer. Who has the more disabling problem: someone with 50% of his body surface covered in psoriasis, but who largely ignores this and has a happy family life and a productive job, or one with 5% involvement whose social life is ruined by it? The concept of ‘body image’ is useful here. All of us think we know how we look, but our ideas may not tally with those of others. The nose, face, hair and genitals tend to rank high in a person’s ‘corporeal awareness’, and trivial lesions in those areas can generate much anxiety. The facial lesions of acne, for example, can lead to a huge loss of self-esteem, and, for some reason, feelings of shame. This is the term applied to distortions of the body image. Minor and inconspicuous lesions are magnified in the mind to grotesque proportions. This is a form of dysmorphobia. The clinician can find no skin abnormality, but the distress felt by the patient leads to anxiety, depression or even suicide. Such patients are not uncommon. They expect dermatological solutions for complaints such as hair loss, or burning, itching and redness of the face or genitals. The dermatologist, who can see nothing wrong, cannot solve matters and no treatment seems to help. Such patients are reluctant to see a psychiatrist although some may have a monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis. These patients sustain single hypochondriacal delusions for long periods, in the absence of other recognizable psychiatric disease. They may become eccentric and live in social isolation. Some believe that they have syphilis, AIDS or skin cancer. Others hide in shame from an inapparent body odour. Still other patients have the delusion that their skin is infested with parasites. Figure 23.2 Delusional infestation – the sequence of events. This term is better than delusions of parasitosis as not all delusions are related to parasites or indeed pathogenic organisms. Parasitophobia implies a fear of becoming infested; patients with delusional infestation are unshakably convinced that they are already infested. No rational argument can convince them that they are not. Many see parasites move on their skin, feel them crawl (formication) or need to dig them out. The pest control agencies that they have called in, and their medical advisers therefore must all be wrong. More recently, patients have begun to describe a condition called Morgellons disease, which involves intense cutaneous dysaesthesia associated with the extrusion of inanimate fibres from the skin surface. This dermatological non-disease has been somewhat perpetuated by ever-increasing internet access and the US media which have attempted to give some credence to its existence; most dermatologists still consider it to be a monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis, a form of delusional infestation. Patients often bring to the clinic samples of extruded fibres or a box of specimens of the ‘parasite’ at different stages of its supposed life cycle. These must be examined microscopically but usually turn out to be fragments of skin, hair, clothing, haemorrhagic crusts or unclassifiable debris. The skin changes may include gouge marks and scratches, but it is correct to consider these patients separately from those with dermatitis artefacta. Although delusional infestation is the most common psychodermatolological presentation, most dermatologists will see only about two to three cases every 5 years and, due to the nature of the condition, it is likely to be significantly under-reported. These patients become angry if doubts are cast on their ideas, or if they are referred to a psychiatrist. How could treatment for mental illness possibly be expected to kill parasites? Family members or friends may share their delusions (folie à deux) and much tact is needed to secure any cooperation with treatment. Direct confrontations are best avoided; sometimes it may be best simply to treat with psychotropic drugs, explaining that these may be able to help some of the symptoms. The delusions of a few of these patients are based on an underlying depression or schizophrenia, and of a further few on organic problems such as vitamin deficiency or cerebrovascular disease. Other patients are addicted to alcohol, metamphetamine, cannabis, cocaine or narcotics. These disorders must be treated on their own merits. However, most patients have monosymptomatic hypochondriacal delusions, which can often be suppressed by treatment with drugs, accepting that these will be needed long term. Otherwise, the outlook for resolution is poor. Patients are ideally treated in joint psychodermatology clinics; however. access to these clinics is limited. It is often more practical to seek advice from psychiatric colleagues regarding therapy.

The Skin and the Psyche

Reactions to skin disease

Body image

Dermatological delusional disease

Dysmorphophobia

Dermatological ‘non-disease’

Other delusions

Delusional infestation (Figure 23.2)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree