The Second Stage in Autologous Breast Reconstruction

David W. Chang

Introduction

With the advent of the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap, the use of autologous tissue has become the preferred method of breast reconstruction in many centers (1,2,3). Although the pedicled TRAM flap and the free TRAM flap remain the most popular method of autologous tissue breast reconstruction, other options, such as the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap, the free deep inferior epigastric perforator flap, the free superior gluteal artery perforator flap, and the free superficial inferior epigastric artery flap, are also available (4,5,6).

The overall goal of autologous tissue breast reconstruction is to transfer well-vascularized tissue to the mastectomy site and create a breast mound that anatomically and aesthetically appears as normal as possible. In cases of unilateral breast reconstruction, the goal is to the match the opposite breast in size and shape. Accomplishing this goal usually requires more than one procedure.

After creation of the breast mound, a second-stage surgery is frequently performed to revise the reconstructed breast to achieve the final desired size and shape. Occasionally, surgical intervention on the opposite breast may be needed as well (7,8). Other procedures that may be done during this second stage include excision of fat necrosis, correction of inframammary fold asymmetry, scar revisions, minor touch-ups to the abdominal donor area, and nipple-areola reconstruction.

During the initial breast reconstruction, it is often not possible to make a breast that will exactly match the size and shape of the opposite breast. One reason is the positioning of the patient. Even if the breast is shaped with the patient in the upright sitting position as much as possible, the full effect of gravity when the patient is standing cannot be duplicated on the operating table. In addition, there are limitations as to how much shaping can be performed without jeopardizing the blood supply and the viability of the flap. Furthermore, since the shaping of the breast is heavily dependent on the surgeon’s artistic judgment and skills, it is reasonable to expect that the final “finished product” will need some touch-ups in many or even most cases. Finally, the initially reconstructed breast rarely, if ever, completely retains its original shape or size. As the flap and the surgical site heal together, the reconstructed breast’s size and shape continue to evolve. For these reasons, some revision of autologous tissue breast reconstruction is often necessary.

Planning

The extent of the revision surgery can vary from a minor outpatient surgery with local anesthesia to more major intervention requiring general anesthesia. Often the type and extent of the revision can be planned during the initial reconstruction of the breast. That is, during the initial breast reconstructive surgery, shaping and insetting of the flap can be done in such a way that the second-stage revision surgery, if needed, will be minor.

For example, it is better to make the initial breast mound volume slightly larger than the contralateral breast. In most instances, mild shrinkage in the volume of the reconstructed breast will occur. Furthermore, a breast that is slightly too large can usually be readily revised with liposuction or direct excision (Fig. 74.1). However, an overzealous attempt at achieving a “perfect” volume match at the time of the initial breast reconstruction can sometimes result in a breast that is smaller than desired (Fig. 74.2). If the initial reconstructed breast is too small, the second operation for adjustment will not be simple. A reconstructed breast that is significantly smaller than the opposite breast can be corrected only with an augmentation of the reconstructed breast or with reduction of the opposite native breast.

When insetting the flap for autologous tissue breast reconstruction, it is important to focus on the superior and medial areas of the breast to ensure an adequate cleavage volume. A slightly overcorrected cleavage region can be easily revised with suction-assisted lipectomy (SAL). In contrast, an undercorrected cleavage, resulting from deficiency of tissue volume in the superior and medial portions of the breast, can be difficult to correct; usually, the flap needs to be reelevated and advanced to fill the hollow area, which can be a major procedure.

Another area on which a surgeon needs to focus during the breast reconstruction is to make sure the level of the inframammary fold is correct. An inframammary fold that is created too high or too low during the initial reconstructive procedure is often difficult to correct. However, if one is to err, it is better to err on the side of making the fold slightly too high than too low. I find it easier to lower an inframammary fold that is too high than to move up an inframammary fold that is too low.

By planning and thinking ahead during the initial insetting and shaping of the flap for breast reconstruction, one can essentially “set up” for the second-stage procedure so that if a revision is needed, only a minor touch-up is required rather than a major procedure.

Timing

A reconstructed breast rarely, if ever, completely retains the original shape or size that was created by the reconstructive surgeon on the operating table. As the flap and the surgical site heal together, the reconstructed breast’s size and shape change.

The optimal time for secondary shaping procedures is after the reconstructed breast has healed, when the flap is completely soft and postsurgical swelling has dissipated. In general, it takes at least 3 months for reconstructed tissues to settle and for postsurgical swelling to subside. However, the timing of the second-stage procedure should be determined on a case-by-case basis. When there is uncertainty, it is generally better to wait than to do the secondary revisions prematurely. For patients who require chemotherapy, secondary shaping procedures usually are delayed for at least 4 weeks after the completion of chemotherapy to allow the immune system to return to normal. For patients who require postoperative radiation therapy, secondary shaping procedures are deferred for at least 3 months after the completion of radiation treatment. Revision of the irradiated breast is discussed further later in this chapter.

Breast Mound Revision

The techniques that are most commonly used to revise the size or shape of a reconstructed breast mound are SAL, direct excision of excess tissue, reduction mammaplasty techniques, and internal shifting of the tissue within the breast mound. Alteration of the contralateral breast also may be needed.

Suction-Assisted Lipectomy

The simplest approach to reducing the size of a reconstructed breast when the overall shape is pleasing and the volume excess is not substantial is SAL. Liporemodeling of the reconstructed breast is more thoroughly discussed in Chapter 77.

One advantage of SAL is that it can reduce the size of the breast mound without markedly changing its shape or creating additional scars (Fig. 74.3). SAL is especially useful for reducing areas that are not easily accessible for direct excision, such as the medial or superior part of the breast mound in a patient who has had an immediate reconstruction after a skin-sparing mastectomy. Use of a tumescent technique (e.g., with a 1/1,000,000 epinephrine wetting solution) during SAL can help minimize blood loss (9,10,11).

For overall reduction of breast size, SAL works best when only a moderate reduction is required. Although in most cases SAL does not significantly alter the shape of the reconstructed breast, decreasing the breast volume can sometimes make the breast appear more ptotic and natural in shape.

Another application of SAL is correcting a contour deformity at the costal margin produced by the carrier muscle following a conventional pedicled TRAM flap. In most cases, this can be readily treated with SAL of the xiphoid region at the time of the second-stage procedure on the reconstructed

breast. Suction in this area is kept relatively superficial to promote adherence of the overlying skin.

breast. Suction in this area is kept relatively superficial to promote adherence of the overlying skin.

Direct Excision

For a more radical reduction in size or change in shape, direct excision is usually necessary. A common problem after breast reconstruction is excessive lateral tissue. This is more of a problem when a breast is reconstructed with a free TRAM flap following a modified radical mastectomy. When a complete axillary node dissection has been performed, the thoracodorsal artery and vein are often used as recipient vessels since they are already exposed. To minimize tension on the pedicle and the anastomoses, the flap is frequently inset more laterally, resulting in lateral fullness. Furthermore, axillary dissection itself can lead to more fullness laterally as a result of surgical dissection and postsurgical changes to the surrounding soft tissues.

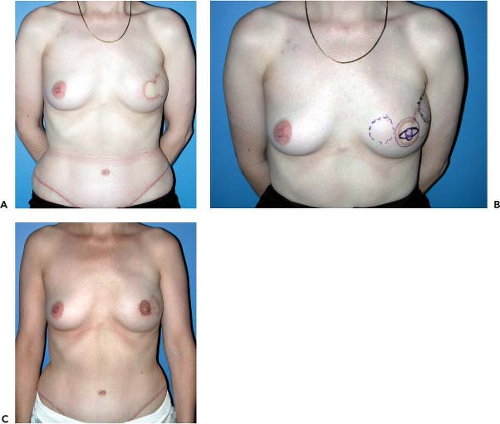

With the advent of sentinel node biopsy and the use of the internal mammary vessels as recipient vessels, flaps can now be inset more medially, and the problem with lateral fullness has become less common in my experience. In addition, with sentinel node biopsy, skin-sparing mastectomy is often performed through a periareolar incision rather than the “lollipop” or “racket” incision usually used with complete axillary node dissection. With this periareolar approach of skin-sparing mastectomy, the integrity of the entire breast envelope is better preserved, also contributing to less lateral fullness (Fig. 74.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree