The Process of Breast Augmentation: Four Sequential Steps for Optimizing Outcomes for Patients

William P. Adams Jr., M.D.

Dallas, Texas

From the Department of Plastic Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Received for publication February 23, 2008; accepted June 2, 2008.

Reprinted and reformatted from the original article published with the December 2008 issue (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1892–1900).

Copyright ©2012 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons

DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318250891f

Disclosure: The author is an investigator for the Allergan/Inamed and Mentor IDE Cohesive gel implant studies, medical director of the Mentor CPG Cohesive Gel Study 2002–2007, and a consultant for Allergan, Ethicon, TyRx, and Axis Three.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. A direct URL citation appears in the printed text; simply type the URL address into any web browser to access this content. A clickable link to the material is provided in the HTML text and PDF of this article on the Journal‘s Web site (www.PRSJournal.com).

Background: Breast augmentation has been an integral part of plastic surgeons’ practices for over 40 years. Although devices have evolved, patient outcomes are still not ideal, as documented in multiple premarket approval clinical trials. Unlike many other areas of surgery, the practice of breast augmentation has suffered from the lack of a defined process for patient management. The purpose of this study was to clinically define and evaluate the process of breast augmentation and analyze patient outcomes using these practices compared with existing premarket approval trial data.

Methods: Three hundred consecutive primary breast augmentations from 2001 to 2005 were followed prospectively. Each patient underwent a defined process of breast augmentation including structured patient education and informed consent; tissue-based preoperative planning consultation; refined surgical technique; and structured postoperative instructions, management, and follow-up.

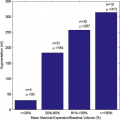

Results: The mean follow-up was 2.1 years. The most common complications were rippling and palpability, soft-tissue stretch, and hypersensitivity. The overall reoperation rate was 3.7 percent for the entire group and 4.7 percent and 2.9 percent for saline and form-stable cohesive gel implants, respectively.

Conclusions: Optimizing patient outcomes in breast augmentation requires defining the overall process to allow for enhanced patient outcomes. This is the first report that defines and integrates the entire process comprehensively that is validated by outcomes data. This process is transferable to other surgeons and, using this algorithm, patient outcomes in this study were superior to premarket approval clinical trial data. In summary, approaching this procedure with a global process produces superior patient outcomes in breast augmentation. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 122: 1892, 2008.)

Aprocess is defined as a group of practices that are completed successively to reach a goal. For 45 years, breast augmentation has been thought of as an isolated surgical procedure; however, well-documented elevated reoperation rates of 15 to 24 percent over 6 years in successive premarket approval studies have resulted in a critical analysis of this procedure.1,2 Factors that impact outcomes have been identified and practice recommendations have been established.

This analysis has resulted in a redefinition of this procedure to a much broader process beyond the actual surgical placement of the implant. Essential components include comprehensive patient education that enhances informed consent, tissue-based preoperative planning, refined surgical technique and rapid recovery, and a strictly defined postoperative management plan. Previous reports have defined individual key areas, and these principles have been integrated, refined, and customized into a comprehensive process that encompasses every key surgeon-staff-patient action point. Although each component may exist individually, the combination of these steps in succession has resulted in enhanced outcomes for patients far better than any one component practiced in isolation. In recent years, as key components of this process have been elucidated, it has been demonstrated that the process is transferable and reproducible.3–5 The purpose of this study was to clinically define and evaluate the process of breast augmentation and to prospectively analyze patient outcomes using these practices compared with existing premarket approval trial data.

Patients and Methods

All patients were treated by a single surgeon’s practice. Patients were followed prospectively from 2001 to 2006. A subgroup of the patients were followed in a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved clinical trial with clinical research organization oversight. The four primary subprocesses used for patient care were structured patient education, tissue-based clinical analysis, refined surgical technique, and defined postoperative regimen (Fig. 1).

Patient Education and Informed Consent

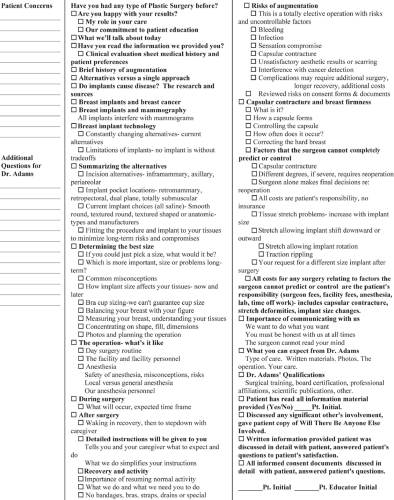

All patients underwent a patient education and informed consent process using a multimodality approach. Initial contact included verbal information and a web-based introduction to the practice philosophy of breast augmentation. Once the decision for consultation was made, a specific patient education consultation was performed to answer specific issues about breast augmentation. After 2002, a specific set of breast augmentation education and informed consent documents (see Documents, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/A568) was customized based on previous publications in this Journal.6 Patients were required to complete the documents before their education consultation that was performed either over the phone or in person, lasting on average 45 to 60 minutes, and performed by a patient education specialist. During the education consultation, all concepts, issues, and limitations were addressed directly and covered with the patient, ultimately having the patient assume responsibility for the final decisions (Fig. 2).

Tissue-Based Clinical Analysis and Planning

The surgeon consultation was performed only after successful completion of the education consultation. The average surgeon consultation time was 30 minutes. The two primary goals of the surgeon consultation were to objectively evaluate the patient’s breast and to ensure that the patient’s goals (previously defined in writing during the education consultation) were reasonable based on their breast dimensions and tissue. The tissue-based evaluation was based on previously published techniques.3 The basics of the High Five process allow the

surgeon to preoperatively make the five critical decisions that determine outcomes for a breast augmentation:

surgeon to preoperatively make the five critical decisions that determine outcomes for a breast augmentation:

Pocket plane.

Implant size (based on predicted tissue-based optimal fill volume of the breast).

Implant type.

Inframammary fold position.

Incision.

The implant size and type were based on two key factors: breast width and breast type (skin envelope compliance and preoperative fill). The rationale for selecting the individualized implant was reviewed with the patient and anyone else participating in the decision-making process.

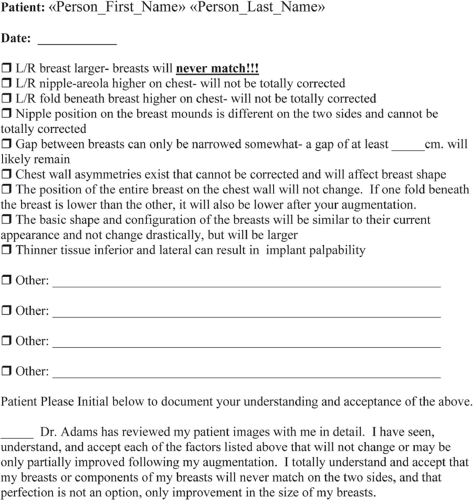

The patient’s breast photographs were also reviewed with the patient and a photograph-analysis sheet (Fig. 3) was completed and initialed by the patient. Patient asymmetries were identified (size and shape) and discussed, and the reality that the postoperative breast will not “match,” realistic expectations for cleavage based on current intermammary distance, rationale for recommended pocket plane, and likelihood of implant palpability, particularly in the inferior and lateral parts of the breast, were all addressed directly with the patient by the surgeon while viewing the photographs.

Refined Surgical Technique

The surgical plan was developed preoperatively following the surgeon consultation. All operations were

performed under general anesthesia with short-acting full muscle paralysis, and patients were premedicated with a single dose of 400 mg of Celebrex (Pfizer, New York, N.Y.). The new inframammary fold incision was planned and executed as previously described.3 Implant pockets were created under direct vision with no blunt dissection using techniques to minimize tissue trauma.7–9 The same surgical principles were applied to all implant types, including smooth, round, and textured anatomical implants. Pocket preparation included the use of triple antibiotic irrigation and other techniques to minimize contamination of the implant, including glove change and wiping the skin before implant placement.8 Sizers were not found to be necessary in [297 of 300 (99 percent)] of cases, and the implant selection was determined during the preoperative consultation before the operative day. Incision closure was performed in three layers using a deep absorbable suture (3-0 Vicryl; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, N.J.) for closure of the superficial fascia of the breast, a deep subdermal suture (4-0 polydioxanone), and subcuticular skin closure (4-0 Monocryl; Ethicon).

performed under general anesthesia with short-acting full muscle paralysis, and patients were premedicated with a single dose of 400 mg of Celebrex (Pfizer, New York, N.Y.). The new inframammary fold incision was planned and executed as previously described.3 Implant pockets were created under direct vision with no blunt dissection using techniques to minimize tissue trauma.7–9 The same surgical principles were applied to all implant types, including smooth, round, and textured anatomical implants. Pocket preparation included the use of triple antibiotic irrigation and other techniques to minimize contamination of the implant, including glove change and wiping the skin before implant placement.8 Sizers were not found to be necessary in [297 of 300 (99 percent)] of cases, and the implant selection was determined during the preoperative consultation before the operative day. Incision closure was performed in three layers using a deep absorbable suture (3-0 Vicryl; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, N.J.) for closure of the superficial fascia of the breast, a deep subdermal suture (4-0 polydioxanone), and subcuticular skin closure (4-0 Monocryl; Ethicon).

Fig. 3. Patient image analysis factors unlikely to change or be totally corrected after breast augmentation. |

Table 1. Postoperative Regimen | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Postoperative Regimen

All patients were given detailed defined postoperative instructions (Table 1). These were reinforced before the day of surgery and on the day of surgery, and verification of compliance was completed after the patient returned home. Patient outcomes, complications, and recovery were assessed and analyzed.

Table 2. Patient and Implant Demographics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3. Pocket Plane | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree