11 The oncoplastic approach to partial breast reconstruction

Synopsis

Breast conservation therapy increases in popularity, driven by equivalent survival rates, preservation of body image, quality of life and reduced physiological morbidity.

Breast conservation therapy increases in popularity, driven by equivalent survival rates, preservation of body image, quality of life and reduced physiological morbidity.

Poor cosmetic results following BCT are not uncommon and are usually due to breast shape, tumor size, tumor location, and postoperative radiation.

Poor cosmetic results following BCT are not uncommon and are usually due to breast shape, tumor size, tumor location, and postoperative radiation.

Partial breast reconstruction is indicated whenever the potential for a poor cosmetic result exists, or patients with tumors in whom a standard lumpectomy would lead to breast deformity or gross asymmetry.

Partial breast reconstruction is indicated whenever the potential for a poor cosmetic result exists, or patients with tumors in whom a standard lumpectomy would lead to breast deformity or gross asymmetry.

The history behind partial breast reconstruction

Breast conservation therapy increased in popularity from 40% in 1991 to 60% in 2002 when compared with mastectomy, and that trend continues to rise.1 This is in part driven by equivalent survival rates and by preservation of body image, quality of life and reduced psychological morbidity with breast sparing surgery.2,3 However, there remains an innate conflict between the goals of oncology and cosmesis, with the former being to eliminate all locoregional disease, and the latter relying on preservation of as much breast tissue as possible for optimal aesthetic outcome. The wider the margin of resection, the lower the risk of local recurrence4,5 and it often becomes a dilemma for the surgeon to meet both these end-points. Breast shape becomes compromised and significant contour deformities, breast asymmetry and poor aesthetic outcomes are not uncommon. Up to 30% of women will have a residual deformity that may require surgical correction,6 the correction of which is often difficult.7 The quadrantectomy type defects in Europe were initial drivers for partial breast reconstruction and partial breast reconstruction was initially performed secondarily following radiation therapy. These defects are far more difficult to reconstruct, which led to a movement focusing more on aesthetics and immediate reconstruction of these partial defects.8,9 It became evident that partial breast reconstruction not only broadened the indications for BCT in some patients but also significantly improved cosmetic results; the combination of which allows removal of larger amounts of breast tissue with safer margins without compromising the cosmetic outcomes. Although these principles evolved in Europe in the 1990s, the actual term “oncoplastic surgery” was introduced in 1993 by Dr Audretsch, in Germany.10 The initial focus of oncoplastic surgery was on breast deformities following quadrantectomy. The greater the defect, the higher the demand was for partial breast reconstruction. However, as similar deformities were being noticed after lumpectomy and radiation therapy as well, this approach has also become popular for the reconstruction of lumpectomy defects. The concept became one of preventing BCT deformities rather than having to reconstruct them. The quadrantectomy defects, and the fact that many breast surgeons in Europe did their own reconstruction made the early adoption there fairly seamless. It was quickly adopted in France, Italy, and the UK. The oncoplastic approach has gained momentum since 2000, and has recently become popular in America11,12 and other parts of the world. The importance of teamwork and communication between the various services is critical for the successful incorporation of the oncoplastic approach. Its popularity will likely continue as long as we continue to demonstrate oncological safety and improved outcomes.

Disease process

Poor cosmetic results following BCT are not uncommon and are usually due to breast shape, tumor size, tumor location, and postoperative radiation (Fig. 11.1).13 Traditionally, women with large breasts have been deemed poor candidates for breast conservation surgery, because of reduced effectiveness, increased complications and worse cosmetic outcome. The post-radiation sequela in women with macromastia is significantly worse. Radiation-induced fibrosis is thought to be greater in women with larger breasts, late radiation fibrosis is higher, and cosmetic results are also reduced.14–16 Tumor location also plays a role with central or lower quadrant tumors having a worse cosmetic outcome. Lower quadrant tumors give twice as poor cosmetic results as lumpectomies in other quadrants. Central breast tumors close to the areolar have in the past been a contraindication to BCT. The tumor to breast ratio is one of the most important factors when predicting the potential for a poor outcome. Studies have shown a decline in cosmetic scores for patients with parenchymal resection greater than 70–100 cm3, or when the specimen weight to breast volume ratio exceeds 10 : 1.17–19 It is important that the reconstructive surgeons have an idea on the extent of the resection, whether lumpectomy or quadrantectomy. In general, when more than 20% of the breast is excised with partial mastectomy, the cosmetic result is likely to be unfavorable.

Patient presentation and selection

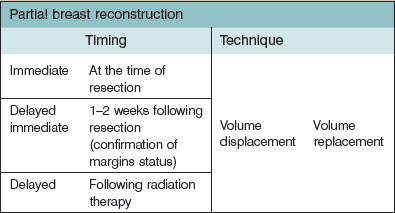

The initial consideration to partial reconstruction needs to come from the breast surgeon, demonstrating the importance of them being aware of the potential concerns with BCT alone and the various options available for these patients (Table 11.1).

Hints and tips

• Consider the oncoplastic approach for patients with a high tumor to breast ratio (>20%), especially in women with small to moderate sized breasts.

• Certain tumor locations (central, inferior, medial) can result in unfavorable aesthetic results with BCT alone.

• Women with macromastia who undergo partial mastectomy are often best treated with a simultaneous reduction procedure.

• The oncoplastic approach will often allow generous resection and can be used when wide excision or quadrantectomy is required or concerns exist about clearing margins.

• Older, obese or high risk patients are poor candidates for SSM and reconstruction and BCT with partial breast reconstruction is often a preferred approach.

• Women with small breasts who desire BCT will often required partial reconstruction to preserve shape and symmetry.

Timing of partial breast reconstruction

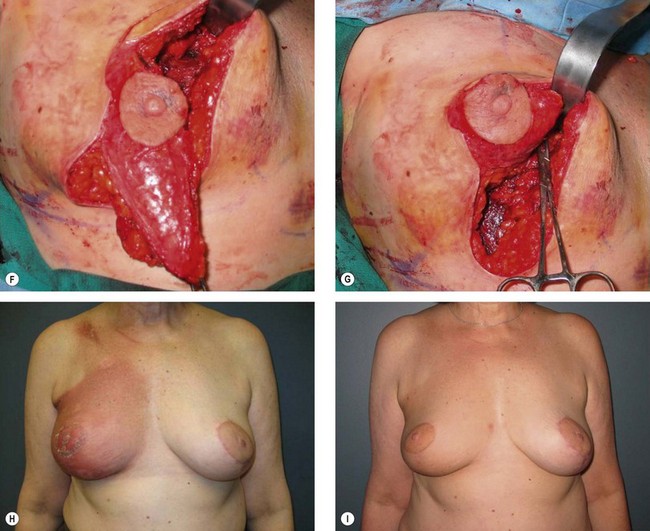

In general, partial breast reconstruction, when indicated is best performed at the time of resection (immediate reconstruction). This has the benefits of operating on a nonirradiated or surgically scarred defect, resulting in lower complication rates and improved aesthetic results.7 The main concern with immediate reconstruction is the potential for positive margins. When this concern does exist, the reconstruction can be delayed until final confirmation of negative margins (delayed-immediate reconstruction). This then allows the benefits of reconstruction prior to radiation therapy with the luxury of clear margins, although at the expense of a second procedure (Fig. 11.2). Patients at increased risk of positive margins included younger age (<40 years old), extensive DCIS, high grade, history of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, infiltrating lobular carcinoma, Her2/neu positivity.20–22 The main disadvantage is the need for a secondary procedure, which might be unnecessary in the majority of cases. When a flap reconstruction is required, we prefer to confirm final margin status prior to partial breast reconstruction.

There are situations where poor results are encountered years following radiation therapy, which then require correction (delayed reconstruction). Similar techniques are employed in delayed reconstruction, more often requiring flaps such as the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap and associated with higher complication rates (42% versus 26%) and worse cosmetic outcome.7

Management of margins

The importance of negative margins in BCT cannot be overstated, and has been associated as a factor for increased local recurrence, especially in younger patients.23 Oncological principles should be applied with equal stringency. This becomes even more critical when reconstructive procedures have been performed since positive margins on final pathology are potentially complicated by altered architecture or elimination of a potential reconstructive option. Careful attention to patient selection and margin status should be performed and every attempt should be made to ensure negative margins. Preoperative breast imaging (i.e., MRI, ultrasound or mammography) is helpful in determining the extent of the disease guiding the necessary resection and should be employed judiciously when indicated. An imaging study showed that tumor size was underestimated 14% by mammography, 18% by ultrasound, whereas MRI showed no difference when compared to the pathological specimen.24 Wire identification and bracketing wires placed preoperatively will localize the extent of resection.25 Intraoperative margin assessment requires multidisciplinary, coordination between the surgeons, the pathologist and the radiologist. Multicolored inking kits have proven to be more accurate than traditional stitch markings,26 especially for the more complex designed oncoplastic specimens. Additional intraoperative confirmatory procedures include gross examination, radiography of the specimen, intraoperative frozen sections for invasive cancer and touch cytology. Separate cavity margins sent at the time of lumpectomy significantly reduces the need for re-excision. Cao and co-workers demonstrated that final margin status was negative in 60% of patients with positive margins on initial resection.27 Rainsbury established a one-stage approach, where bed biopsies are taken from the cavity and subareolar region and sent for frozen section. The entire cavity is then inked and sent as a shave specimen for formal histology.28 If tumor is still present in the second set of biopsies, then a mastectomy is indicated.

Although actual data is limited, some have proposed that the positive margin rate following oncoplastic resections should be lower, given the ability to perform a generous resection. Oncoplastic resections in some series have been over 200 g compared with institutional norms of about 40–50 g using lumpectomy alone.22,29 This does not include the additional glandular excisions necessary to achieve symmetry with the reduced contralateral breast in patients with macromastia. Kaur et al. demonstrated an oncological benefit in a comparative study where positive margins were identified in 16% of breast cancer patients who had the oncoplastic approach versus 43% in patients with quadrantectomy.30 Comparisons in the literature are difficult given the varying institutional definitions of what constitutes a positive margin, however, positive margin rates in most oncoplastic series range from 5–10%7,22,30 compared with the larger BCT series of 10–15%.2,3

Surgical planning

Treatment algorithm for partial reconstruction

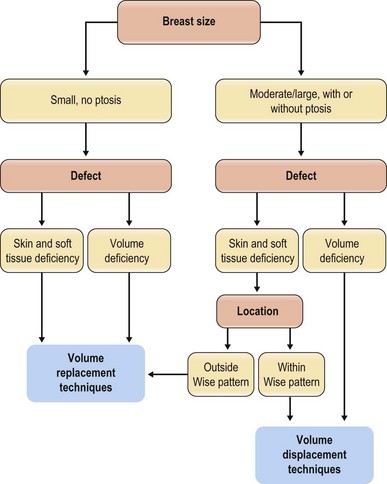

Different algorithms have been described in an attempt to simplify the reconstructive process.31 There is, unfortunately, a lack of standardization when it comes to partial breast reconstruction, which makes comparative studies difficult. The decision as to which procedure is more appropriate is multifactorial, however, and is ultimately determined by breast size, tumor size, and tumor location. Other factors are also important, including patient risks and desires, tumor biology, and surgeon comfort level with the various techniques. Another way of looking at this is to evaluate the amount of breast tissue that remains following completion of the partial mastectomy, and where that tissue is in relation to the nipple areolar complex, since this will dictate the most appropriate reconstruction option for that particular case. Adhering to strict algorithms is difficult, since every case is different. Being familiar with the various reconstructive tools will allow reconstruction of almost any partial mastectomy defect. It is important to keep in mind that when the defect is extensive with little remaining breast tissue, then completion mastectomy and immediate reconstruction is often the more appropriate option. Kronowitz et al. found that most women with medium to large breasts benefit from immediate reconstruction, and that when immediate reconstruction is performed, the preferred technique is local breast tissue – local tissue rearrangement of reduction techniques.31

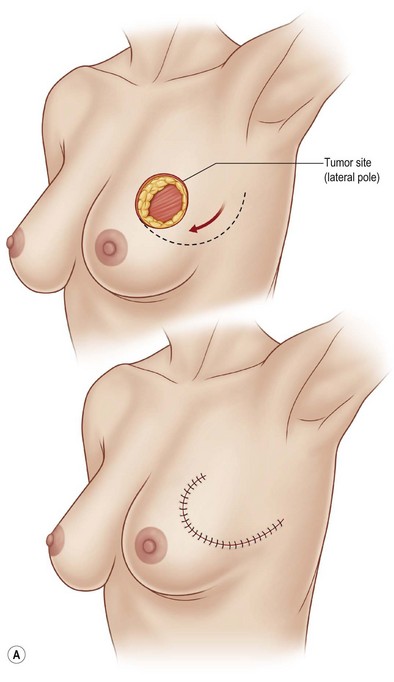

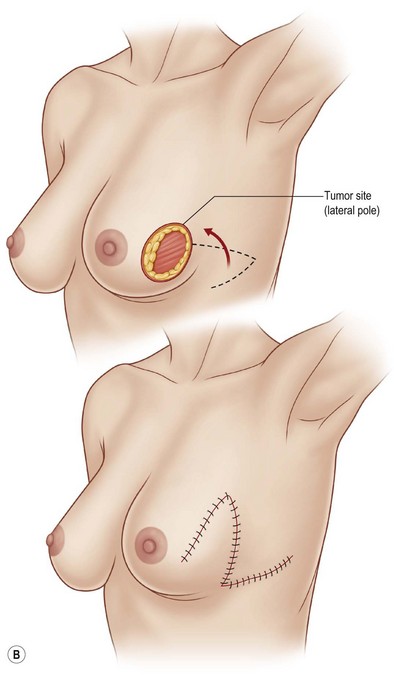

Some simple rules of thumb exist for reconstructing partial mastectomy defects (Fig. 11.3). Large or moderate sized breasts, or ptotic breasts with sufficient parenchyma remaining following resection, are amenable to volume displacement or reshaping procedures. Quadrantectomy-type resections are possible when within the standard Wise pattern markings. In smaller, or nonptotic breasts, when additional volume is required to match the opposite breast or when skin is required to replace a resection that included parenchyma and skin, then volume replacement procedures, including volume and skin are required (Table 11.2). Quadrantectomy type resections in small breasts, and in the upper or outer quadrant will invariably require a flap reconstruction to preserve shape (Fig. 11.4).

Table 11.2 Partial mastectomy reconstruction techniques

| Volume displacement techniques | Volume replacement techniques |

| “Parenchymal remodeling, volume shrinkage” | “Adjacent or distant tissue transfer, volume preserving” |

| Primary closure | Implant augmentation – rare |

| Mirror biopsy/excision | Local flaps |

| Batwing mastopexy | Fasciocutaneous |

| Breast flap advancement technique | Perforator flaps |

| Nipple areolar centralization | Latissimus dorsi MC flap |

| Reduction mastopexy techniques | Distant flaps |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree