CHAPTER 1 The History of Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery

Whether regarding cosmetic oculoplastic surgery or life in general, a knowledge of the history that brought us to the present provides many advantages, most of which relate to warnings of potential unfortunate events, or encountering concepts that have been already discovered. If one knows the history, one can benefit from the experiences of others, and even endeavor to improve upon existing methods. Far too often, I read about or watch surgeons display their ‘discoveries’ only to be disappointed that they were unaware of, or do not acknowledge, those before them who, even many years previously, had authored the same results. So many of the procedures discussed today in the literature, at meetings, and in this text have roots far back in time. In this chapter, I have added to the comprehensive writings of Larry Katzen, who traced back some of the pinnacle historical discoveries of periorbital surgery. For instance, in his research, he found that the first recorded resection of excessive upper eyelid skin was performed over 2000 years ago. Many other procedures performed today such as resection of orbital fat, and the formation of the upper eyelid crease also have a long history, as do the appreciation and value of reviewing preoperative photographs, and cultural-specific attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. In this chapter, we will present some of the historical discoveries and developments of cosmetic oculoplastic surgery that have brought us to the present.

Ancient medicine

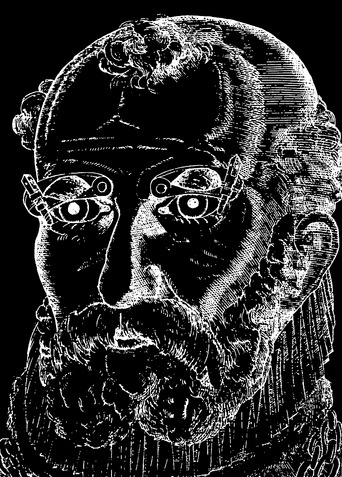

Cosmetic eyelid surgery today has the benefit of 2000 years of development and refinement of surgical techniques and instruments. Ali ibn Isa (AD 940–1010) described the procedure just quoted more than 1000 years ago (Fig. 1-1), at a time when his medical treatment for ‘oedema of the lids’ was ‘letting blood from the head, and treating the eye with a preparation of celandine, sandlewood, and endives….’1

Aulus Cornelius Celsus, a Roman encyclopedist and philosopher in the first century, was probably the first to comment on the excision of skin of the upper eyelids when he described the treatment of ‘relaxed eyelid’ in his De re Medica (AD 25–35).2 De re Medica was not published until 1478, following its rediscovery by Pope Nicholas V.

Even before Celsus, the Hindus were known to have referred to cosmetic and reconstructive surgery about the face. The accepted form of corporal punishment in India 2000 years ago was amputation of the nose. The surgeons of this time became so skilled in reattaching this appendage that officials began to throw the amputated nose into the fire to ensure their goal of disfigurement. It is interesting that the skilled surgeons who were able to reattach the nose successfully were actually members of the lowly tile makers’ caste.3

Modern cosmetic eyelid surgery

Blepharoplasty (Greek blepharon, meaning eyelid, and plastos, meaning formed) was originally used by von Graefe4 in 1818 to describe a case of eyelid reconstruction that he had performed in 1809. This meaning prevailed for the next 150 years.

In the 1913 American Encyclopedia of Ophthalmology,5 blepharoplasty is defined as the reformation, replacement, readjustment, or transplantation of any of the eyelid tissues. In contemporary usage, blepharoplasty refers to the excision of excessive eyelid skin, with or without the excision of orbital fat, for either functional or cosmetic indications. The cosmetic indications have been recognized by physicians only since the turn of the 20th century, but are now the most common reasons for such surgery on the eyelids. This change followed the development of improved operative techniques, better surgical results, and control of sepsis as well as changing social mores.

It is difficult to determine whether the ‘relaxed eyelid’ described by Celsus was a true ptosis or an excess skin fold. In any event, by the late 1700s, reports began to appear in Germany6 specifically identifying the excess fold of the upper eyelid. Beer’s 1817 text is credited with providing the medical literature with the first illustration of this eyelid deformity.7 Many different authors from the first half of the 19th century began advocating excision of this excess skin, including Mackenzie,8 Alibert,9 Graf,10 and Dupuytren.11

The first ‘accurate’ description of ‘herniated orbital fat,’ written in 1844 by Sichel,12 did not create a wave of surgical excisions because surgery at that time was performed only for functional reasons. The case of Fetthernien reported in 1899 by Schmidt-Rimpler,13 which described herniated orbital fat, was clouded by the later report by Elschnig,14 who called the same patient’s condition a lipoma.

Near the turn of the 19th century, Ernest Fuchs15 attempted to decipher the confusing terminology that had developed in the literature. ‘Ptosis adiposa,’ the misnomer used by Sichel, and ‘ptosis atonica,’ used by Hotz,16 had been introduced earlier in the 19th century. Sichel12 had claimed that the excess upper lid fold was filled with fat, which caused it to hang down over the lid margin. Hotz believed that the skin was normally attached to the top of the tarsus, and that the loss of this attachment created an excessive upper lid skin fold with a pseudoptosis. It was Fuchs who recognized the importance of the weakening of the fascial bands connecting the skin and orbicularis with the tendons of the levator in the development of the excess skin fold. In his 1892 text, Fuchs15 wrote:

And so Fuchs was the first to recognize the cosmetic value of reformation and elevation of the eyelid crease. Fuchs17 is also credited with originating the often misused term blepharochalasis in 1896. Sometimes used to describe the changes associated with herniated orbital fat, this term should be reserved for those cases of thickened and indurated eyelids, most often found in younger women, and associated with recurrent episodes of idiopathic edema.18,19 The term dermatochalasis was introduced 56 years later by Fox20 to describe the apparent excess eyelid skin associated with aging.

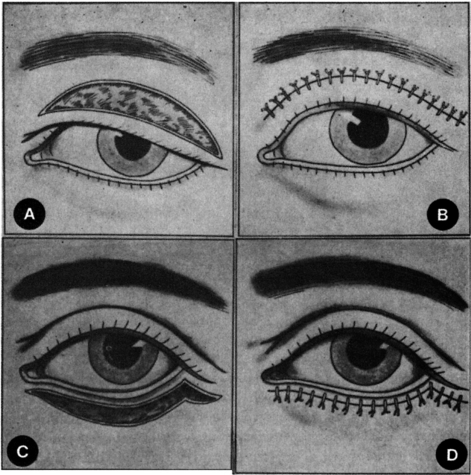

In the early 1900s, the historical focus on cosmetic eyelid surgery shifted to the United States, where Conrad Miller,21 in 1907, produced Cosmetic Surgery: The Correction of Featural Imperfections, the first published book on cosmetic surgery. This edition, which covered many aspects of plastic surgery, contained the first photograph in medical history to illustrate the lower eyelid incision for removing a crescent of excess skin. It is interesting to note Miller’s surgical technique. In his discussion of the lower eyelid incision, Miller stated that ‘just sufficient skin is left along the margin of the lid to permit the stitches being passed in closing. The line of union is brought in this way under the shadow of the lashes, and is entirely invisible.’ On excision of the fold above the eye, Miller wrote that ‘the fold above the eye after infiltration is picked and trimmed away. The line of closure here is at the upper extremity of the lid so that the slight line of the union is hidden in the fold between the lid and the brow when the eye is open, and only shows slightly when the eye is closed.’ Miller’s enlarged text,22 which followed in 1924, provided diagrams of incision sites for upper and lower eyelid blepharoplasty that are remarkably similar to those commonly used today (Fig. 1-2).

Frederick Kolle,23 in a 1911 text on plastic and cosmetic surgery, wrote about wrinkled eyelids in a chapter on blepharoplasty. He probably was the first to recognize and note the safety and value of marking the skin preoperatively to determine the amount of excess skin to excise.

Adabert Bettman24–26 added to the contributions by Miller and Kolle in his publications in the 1920s, in which he described precautions, specifically related to surgery about the eyelids, to be taken in minimizing postoperative scarring. He emphasized gentle treatment of the tissues, exact apposition of wound edges, elimination of tension on all wound edges, and timely suture removal. These, of course, are concepts that are still important today.

The first work in English devoted solely to oculoplastic surgery was written by Edmund Spaeth.27 Newer Methods of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, published in 1925, deals entirely with eyelid reconstruction and does not mention cosmetic surgery.

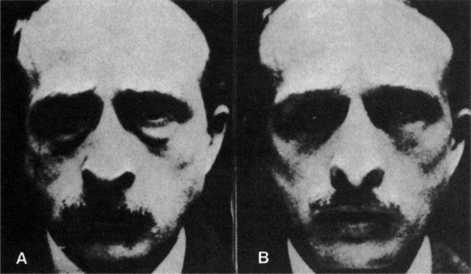

In the same decade in Europe, Julian Bourguet28 was also developing new techniques in cosmetic eyelid surgery. In 1924, he was probably the first to describe transconjunctival resection of the pockets of herniated orbital fat. In the following year, he published probably the first before and after photographs of patients who had undergone cosmetic lower eyelid surgery (Fig. 1-3).29 In 1929, Bourguet30 described the two separate fat compartments of the upper lid and advocated their removal. Many surgeons followed his lead, including Claoué31 and Passot.32 Passot32,33 is also credited as being the first to name the supraciliary brow incision for the correction of brow ptosis. It is also quite interesting that Passot expressed his objections to the secrecy of techniques practiced by some of his contemporaries: ‘By keeping their methods secret, they allow a certain suspicion to exist about their procedures.’34,35 These ‘suspicions’ for many procedures can be related to the present.

At the same time, one of the first female surgeons to appear in the history of cosmetic surgery was perfecting her techniques in Paris.36,37 Suzanne Noel’s 1926 book on cosmetic eyelid surgery38 was the earliest to include numerous preoperative and postoperative photographs.36 Noel also initiated the emphasis, for the benefit of other surgeons, on the advantages and the importance of looking at these photographs and showing them to one’s patients. She was also the first to be photographed performing a blepharoplasty. Thanks to the contributions of Noel and others and to the development of photography as an art and science, photographic documentation is now an integral part of the practice of the cosmetic oculoplastic surgeon. In addition, Noel must certainly be credited for recognizing the importance of the psychological implications of cosmetic surgery for both the patient and the patient’s family. She distinguished between the attitudes of American and European men: ‘American men are anxious to encourage their wives to have such an operation…. [S]uch is not the case with the European male; as a result, French women have the operation performed and do not talk about it.’

In the first two decades of the 1900s, a surgical technique widely used in Europe for elevation of the eyebrow was commonly known as the ‘temporal lift.’ Its benefits remained controversial. Bourguet,39 in 1921, was the first to condemn this type of surgery. In 1926, Hunt40 described a coronal skin resection to achieve a forehead lift. Joseph,41 in 1931, described hairline and forehead crease incisions to raise the brows. The coronal brow lift, as described by Hunt, lost favor because the results with the methods performed in a matter similarly ascribed by him were thought to be too transient.

A number of authors then recognized the importance of manipulating the frontalis and other muscle activity to achieve better results with the forehead lift.35,42–45 The importance of attenuating the action of the procerus and corrugator muscles was recognized by Salvadore Castanares in 1964.46

Since the 1930s, additional individual contributions have been made to cosmetic eyelid surgery. An offering in 1951 by Castanares47 of a detailed description of the fat compartments of the upper and lower orbit and their relationship to the eyelids cannot be overlooked. It was also Castanares48–50 who recognized the importance of the orbicularis muscle (including its hyper-trophy and excision, when indicated) as part of the overall evaluation and technique in cosmetic blepharoplasty.48–50 Furnas51–53 later elaborated on the origin of eyelid and cheek contour abnormalities (including festoons) in his landmark chapter in Clinics of Plastic Surgery edited by Flowers.

In 1954, Sayoc54 reported on the use of the Hotz trichiasis procedure for the cosmetic alteration of the Asian upper eyelid crease/fold complex. Pang’s 1961 report on the Far Eastern method of the surgical formation of the upper lid fold55 was the first to advocate the technique of supratarsal fixation, although this term was reintroduced 13 years later by Jack Sheen.56 Khou Boo-Chai’s 1963 report57 was the initial description of eyelid crease elevation with upper eyelid blepharoplasty, but he advocated dermal fixation to the tarsal plate and referred only to the Asian eyelid.

Significant contributions to cosmetic eyelid surgery in the 1970s focused on the levator aponeurosis and crease-fold complex.58 In 1974, Sheen56 recognized the low eyelid crease as the cause of apparent failure in many Caucasian patients undergoing upper lid blepharoplasty. He advocated orbicularis fixation to the levator aponeurosis 16 mm above the lid margin; 3 years later, iatrogenic postoperative ptosis prompted him to lower it to 12 mm.59 At that time, observing postoperative lid retraction, he inadvertently dis-covered a way to strengthen the levator aponeurosis by tucking it. The next year, Dryden and Leibsohn60 reported on intentional levator advancement for simultaneous blepharoplasty and repair of ptosis. The cur-rent thinking for the next 20 years for a high-definition and enhanced upper eyelid ‘invagination’ with blepharoplasty were in part due to contributions from Flowers61,62 and Siegel.63,64

Putterman and Urist65 recognized the role of the crease-fold complex in upper eyelid asymmetry associated with ptosis, trauma, and other eyelid abnormalities. Sheen66 also advocated tarsal fixation in the lower eyelid to achieve a ‘youthful’ appearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree