Chapter 3

The Head and Neck

- Embryology

- Dental terminology

- Craniofacial surgery

- Cleft lip; cleft lip and palate

- Cleft palate

- Velopharyngeal insufficiency

- Head and neck cancer

- Maxillofacial trauma

- Oculoplastic surgery

- Facial palsy

- Abnormalities of the ear

- Further reading

Embryology

- ‘Branchia’ is the Greek word for ‘gills’.

- Branchial arches are paired swellings along the pharynx of a 4-week-old embryo.

- Humans have six paired branchial arches, but the fifth disappears.

- Each branchial arch contains neural crest cell derivatives:

- A cartilage

- A cranial nerve

- An aortic arch

- Myoblasts.

- First and second branchial arches are most important in facial development.

- Grooves between the arches on their external surfaces are called branchial clefts.

- The cleft between the first and second arch becomes the external auditory meatus.

- The other three clefts disappear.

- Grooves between the arches on their inner surfaces are called pharyngeal pouches, which form:

- First pouch: tubotympanic recess (middle ear, Eustachian tube)

- Second pouch: palatine tonsils

- Third pouch: inferior parathyroids, thymus

- Fourth pouch: superior parathyroids

- Fifth pouch (ultimobranchial body): parafollicular cells of the thyroid.

- Branchial arches are paired swellings along the pharynx of a 4-week-old embryo.

The first branchial arch

- Supplied by the trigeminal nerve and maxillary artery.

- Also known as the mandibular arch, it gives rise to:

- Paired mandibular prominences that contain Meckel’s cartilage.

- This mostly resorbs, but its posterior part forms the malleus.

- The body and ramus of the mandible form from dermal mesenchyme adjacent to Meckel’s cartilage.

- This mostly resorbs, but its posterior part forms the malleus.

- Paired maxillary prominences that form:

- Premaxilla

- Maxilla

- Zygoma

- Squamous portion of the temporal bone.

- Premaxilla

- The quadrate cartilage lies within the maxillary prominence.

- Forms the incus and greater wing of sphenoid.

- Mesenchyme of this arch forms:

- Muscles of mastication

- Anterior belly of digastric

- Mylohyoid

- Tensor veli palatini

- Tensor tympani.

- These are all supplied by the trigeminal nerve.

- Also known as the mandibular arch, it gives rise to:

The second branchial arch

- Supplied by the facial nerve and stapedial artery.

- Also known as the hyoid arch, it contains Reichert’s cartilage, which forms:

- Stapes

- Syloid process

- Lesser cornu and part of the body of the hyoid.

- Stapes

- Mesenchyme of this arch forms:

- Muscles of facial expression

- Posterior belly of digastric

- Stapedius

- Stylohyoid.

- These are all supplied by the facial nerve.

- Muscles of facial expression

The frontonasal process

- Formed by proliferation of mesoderm ventral to the forebrain.

- Not a branchial arch derivative.

- Develops paired placodes (ectodermal thickenings) on its inferolateral borders:

- Medial part of the placode forms the medial nasal process.

- Lateral part of the placode forms the lateral nasal process.

- Medial part of the placode forms the medial nasal process.

- Between the two appears the nasal pit; this becomes the nostril.

- Merging of the medial nasal processes forms:

- The philtrum and Cupid’s bow of the upper lip

- Nasal tip

- Nasal septum

- Premaxilla.

- The philtrum and Cupid’s bow of the upper lip

- The lateral nasal processes form the nasal alae.

Facial development

- Mainly occurs between 4th and 8th weeks of intrauterine life.

- The face is formed from five facial prominences:

- Paired maxillary processes

- Paired mandibular processes

- Frontonasal process.

- Paired maxillary processes

- The medial nasal process fuses with the maxillary process.

- Failure results in cleft lip (CL).

- Bilateral failure of fusion results in a bilateral CL.

- Failure results in cleft lip (CL).

- Failure of midline fusion of the medial nasal processes results in a median CL or Tessier 0 cleft.

- The lateral nasal process fuses with the maxillary process at the alar groove.

- Failure of fusion results in a Tessier 3 cleft.

- Failure of fusion between maxillary and mandibular processes results in macrostomia or Tessier 7 cleft.

- Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), sonic hedgehog (SHH) and retinoic acid have all been implicated.

Cranial development

- Bones of the skull base develop from cartilage precursors, including:

- Sphenoid, ethmoid, petrous temporal and basioccipital.

- Bones of the cranial vault develop in membrane derived from the presumptive dermis, including:

- Frontal, parietal, squamous temporal and squamous occipital.

- At birth, seams of connective tissue called sutures separate the skull bones.

- Where more than two bones meet, there is a wider gap called a fontanelle.

- The posterior fontanelle closes by 3 months.

- The anterior fontanelle normally remains open until 18 months.

- The posterior fontanelle closes by 3 months.

- These fibrous connections allow the skull to deform during childbirth.

- Expansion of the skull is driven by brain growth.

- Brain growth stimulates new bone formation at the suture front.

- Hydrocephalus causes persisting suture patency.

- Microcephaly causes premature suture closure.

- Hydrocephalus causes persisting suture patency.

- The dura plays a key role in controlling suture patency.

The neural crest

- Just prior to fusion of the neural tube, a population of cells known as the neural crest is generated in the area of the neural folds.

- The neural crest contains pluripotential ectomesenchymal tissue.

- Although derived from ectoderm, they exhibit properties of mesenchyme.

- These cells migrate throughout the body.

- They are prevalent within the facial primordia and are essential for normal craniofacial development.

- Teratogens, such as retinoic acid and alcohol, affect neural crest migration.

- Neural crest derivatives encompass:

- The endocrine system, including the adrenal medulla

- The melanocytic system

- Connective tissue, including teeth and bone

- Muscle tissue

- Neural tissue, including the autonomic nervous system.

Developmental terminology and definitions

Malformation

- A morphological defect due to an intrinsic abnormality of development.

- Most common types include:

- Incomplete morphogenesis, such as microcephaly.

- Incomplete closure, such as cleft palate (CP).

- Incomplete separation, such as syndactyly.

- Incomplete morphogenesis, such as microcephaly.

- Malformations initiated earlier in fetal development tend to be more severe.

Deformation

- An abnormality of form or position of a body part due to intrauterine mechanical forces that restrict movement of the developing fetus.

- Deformations can arise from oligohydramnios, bicornuate uterus or twin pregnancy.

- Central nervous system (CNS) malformations can cause deformations due to paralysis.

Disruption

- A defect caused by interference with otherwise normal development.

- In utero amputation of a limb due to an amniotic band is a disruption.

Sequence

- Where a single developmental defect results in a chain of secondary defects.

- Secondary defects may cause further tertiary defects.

- The result is a group of defects traceable to an originating event.

- The primary defect in Pierre Robin sequence (PRS) is mandibular hypoplasia.

- The secondary defect is posterior displacement of the tongue.

- This blocks closure of the palatal shelves resulting in a tertiary defect: CP.

Syndrome

- A group of anomalies (symptoms and signs) containing multiple malformations or sequences.

- Collectively they indicate or characterise a particular syndrome.

- In Greek, syn is with; dromos is running.

Association

- A group of anomalies not known to be part of a syndrome or sequence but found in multiple patients.

- Examples include VATER and CHARGE.

- Not specific diagnoses, but alert clinicians to search for other components of the association.

Dental terminology

- Primary dentition is the first set of 20 ‘baby’ or ‘deciduous’ teeth.

- Permanent dentition refers to the 32 secondary ‘adult’ teeth.

- There are two dental arches: maxillary or upper; mandibular or lower.

- Arches are divided into quadrants by the midline, e.g. maxillary right quadrant.

- Teeth are classified by their morphology:

- Incisors have an incisal edge.

- Canines or cuspids have one pointed cusp.

- Premolars or bicuspids have two cusps.

- Molars have three or more flattened cusps.

- Incisors have an incisal edge.

- Tooth position can be recorded as follows:

- Descriptive, e.g. ‘right upper second molar’.

- Palmer notation, the most popular method in the United Kingdom:

- Teeth are numbered according to their position from the midline.

- Baby teeth are assigned a letter from A to E.

- Addition of a symbol (┘ └ ┐ ┌) indicates the quadrant.

- Teeth are numbered according to their position from the midline.

- The universal numbering system is commonly used in the United States.

- Teeth are numbered from 1 to 32, starting at the right maxillary third molar.

- The maxillary arch is numbered 1–16.

- The mandibular arch is numbered 17–32, starting at the left mandibular third molar.

- Baby teeth are assigned a letter from A to T.

- Teeth are numbered from 1 to 32, starting at the right maxillary third molar.

- Descriptive, e.g. ‘right upper second molar’.

- Teeth have a crown above the gum line and a root below.

- A cusp is a pronounced elevation on the occlusal surface.

- A groove delineates the boundary between adjacent cusps.

- Direction is expressed as follows:

- Buccal: towards the cheek

- Labial: towards the lips

- Lingual: towards the tongue

- Palatal: towards the hard palate

- Mesial: towards the median line, following the curve of the dental arch

- Distal: away from the median line, following the curve of the dental arch

- Apical: towards the apex of the root

- Occlusal: towards the biting surface of a posterior tooth

- Proximal surfaces are those between adjacent teeth.

- Buccal: towards the cheek

- Malocclusion is an incorrect relationship between the teeth of the two dental arches.

- Angle classified malocclusion based on a relationship where the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occludes in the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar.

- Normal occlusion has this molar relationship, with normal alignment of the remaining teeth.

- Class I malocclusion has a normal molar relationship, but there may be overcrowding or misalignment of the other teeth.

- Class II malocclusion has a molar relationship where the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar is distally positioned (away from the median line) from the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar.

- Class III malocclusion has a molar relationship where the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar is mesially positioned (towards the median line) from the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar.

- Overbite is the amount of vertical overlap of the mandibular anterior teeth by the maxillary anterior teeth.

- Overjet is the horizontal distance between the maxillary incisors and the mandibular incisors.

- Open bite is lack of vertical overlap of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth or no contact between the maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth.

- Cross bite is a discrepancy in the buccolingual relationship of the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

- Class I malocclusion has a normal molar relationship, but there may be overcrowding or misalignment of the other teeth.

Craniofacial surgery

Classification

- In 1981, the American Cleft Palate Association published the following classification of craniofacial abnormalities:

- Clefts (centric, acentric)

- Synostoses (symmetric, asymmetric)

- Atrophy–hypoplasia

- Neoplasia–hyperplasia

- Unclassified.

- Clefts (centric, acentric)

- Some conditions fit into more than one category:

- Treacher Collins syndrome is not only associated with facial clefts, but also with facial hypoplasia.

Clefts

- Craniofacial clefts are rare.

- Also known as ‘atypical’ clefts, as distinguished from ‘typical’ CL and palate.

- Occur sporadically once in every 25,000 live births.

- Two leading theories of pathogenesis:

- Classic theory – failure of fusion of the facial prominences.

- Mesodermal penetration theory – lack of mesodermal penetration leads to dehiscence of the epithelial elements.

- Classic theory – failure of fusion of the facial prominences.

- Clefts may also arise from intrauterine compression by amniotic bands.

- Identification of the genetic basis of craniofacial syndromes is a rapidly expanding field.

- Environmental causes include:

- Radiation

- Infections

- Maternal infection with toxoplasmosis, rubella or cytomegalovirus.

- Maternal

- Diabetes, phenylketonuria, maternal age, weight and general health.

- Chemicals

- Folic acid deficiency.

- Vitamin A derivatives, such as isotretinoin.

- Folic acid deficiency.

- Radiation

- Overlap exists between clefts and other hypoplastic syndromes.

- Treacher Collins syndrome is a hypoplastic condition of the lateral face.

- Also known as a confluent Tessier 6,7,8 cleft – has features found in all three cleft patterns.

- Clefts can affect any or all layers of the face.

- They may be unilateral or bilateral.

- Bilateral cases may present different clefts on each side.

- Soft tissue defects do not always correspond to the bony abnormality.

- Craniofacial clefts are often associated with hairline markers.

- These are areas of abnormal linear hair growth along the cleft.

Classification

- Anatomical – Tessier’s classification.

- Embryological – Van der Meulen’s classification.

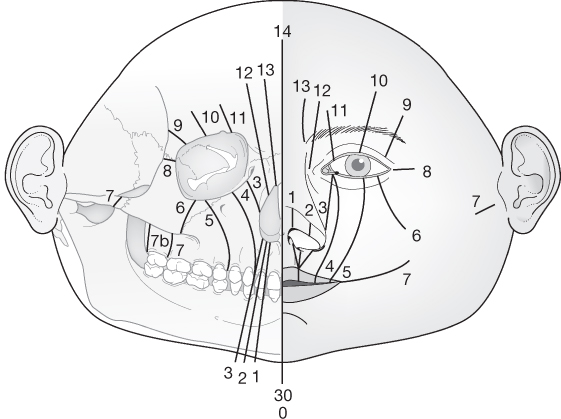

Tessier’s classification

- The most commonly used and internationally accepted.

- Facial clefts extend downwards from the level of the orbit.

- Cranial clefts extend upwards from the level of the orbit.

- A midline cleft is numbered 0.

- Facial clefts are numbered 1–7.

- Start near the midline with a Tessier 1.

- Each sequential facial cleft is more lateral than the last.

- Tessier 7 is the most lateral, extending outwards from the corner of the mouth.

- Start near the midline with a Tessier 1.

- Cranial clefts are numbered 8–14.

- Tessier 8 is the most lateral and extends into the corner of the orbit.

- Thereafter, each sequential cranial cleft is more medial than the last.

- Tessier 8 is the most lateral and extends into the corner of the orbit.

- Facial and cranial clefts can be connected.

- If this occurs, the patterns tend to add up to 14, e.g. 12 + 2.

- Tessier 30 is a midline cleft of the lower lip and mandible.

- David Fisher, from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, rationalises Tessier’s classification as follows:

- ‘Think in groups of three’:

- 0,1,2: lip to nose

- 3,4,5: lip to orbit/lower eyelid

- 6,7,8: Treacher Collins

- 9,10,11: Orbit and upper lid

- 12,13,14: Medial to orbit.

- 0,1,2: lip to nose

- Tessier 3 involves 4 cavities: oral, maxillary sinus, nasal and orbital.

- Tessier 4 involves 3 cavities: oral, maxillary sinus and orbital.

- Tessier 4 is medial to the infraorbital foramen.

- Tessier 5 is lateral to the infraorbital foramen.

- Tessier 7 is macrostomia.

- Tessier 8 is the ‘equator’.

- Tessier 0,14 is nasofrontal dysplasia.

- Tessier 4 is medial to the infraorbital foramen.

- ‘Think in groups of three’:

Source: Tessier (1976). Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Principles of surgery

- Functions: oral competence, speech and eyelid reconstruction.

- Separation of cavities: oral, nasal and orbital.

- Cosmesis.

- The skeleton can be reconstructed by:

- Removing abnormal elements.

- Transposing skeletal components (including distraction osteogenesis).

- Bone grafting skeletal defects.

- Alloplastic implants.

- Removing abnormal elements.

- Musculature is reattached to the skeleton in its correct anatomical position.

- Sphincters should be recreated where possible.

- Soft tissues can be reconstructed with:

- Local, regional or distant flaps with or without prior tissue expansion.

- Use of Z-plasty to redirect scars.

- Local, regional or distant flaps with or without prior tissue expansion.

- Reconstruction is facilitated by a wide surgical exposure.

- Separation of cavities: oral, nasal and orbital.

Hypertelorism

- An increase in the distance between the bony orbits.

- May be seen in the context of facial clefts.

- The intervening ethmoid sinuses (interorbital space) are overexpanded.

- In practice, it is always a congenital condition.

- Trauma cannot cause true widening of the nasal–orbital walls without creating large midline defects.

- In practice, it is always a congenital condition.

- Hypertelorism may prevent development of binocular vision.

- It is also a significant cosmetic problem.

- Telecanthus is an increase in the intercanthal distance (ICD).

- In telecanthus, the distance between the bony orbits may be normal.

- Pseudotelecanthus is the illusion of telecanthus caused by a flat nasal bridge or prominent epicanthal folds.

Classification

- Tessier graded hypertelorism in adults according to interorbital distance (IOD):

- First degree: IOD 30–34 mm

- Second degree: IOD >34 mm

- Third degree: IOD >40 mm

- First degree: IOD 30–34 mm

- A normal adult IOD is 22–30 mm.

- IOD is measured on a posteroanterior (PA) X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan as the interdacryon distance.

- The dacryon is the point of union of lacrimal, frontal and maxillary bones.

Causes

- Hypertelorism is associated with numerous conditions:

- Median and paramedian facial clefts

- Sincipital encephaloceles

- Midline tumours.

- Craniofacial syndromes:

- Apert’s

- Crouzon’s

- Craniofrontonasal dysplasia.

- Apert’s

- Median and paramedian facial clefts

Surgical management

- CT is essential for preoperative planning.

- Ophthalmological assessment of visual acuity, amblyopia or extraocular dysfunction is required.

- The orbits can be repositioned without disturbing the optic nerve because the optic foramina are not displaced.

- Tessier gives these basic principles:

- The 360° orbit must be mobilised to allow adequate translocation.

- The ‘functional orbit’ posterior to the equator of the globe must be mobilised.

- A combined craniofacial approach protects the brain.

- The roof of the orbit is also the floor of the anterior cranial fossa.

- The 360° orbit must be mobilised to allow adequate translocation.

Box osteotomy

- Used for patients with hypertelorism and normal midface width.

- Through a coronal approach, osteotomies are made around each orbit.

- Nasal bones and ethmoid sinus are removed, and the orbits moved medially towards each other.

- Alternatively, two paramedian segments are resected, which preserves the nasofrontal junction and cribriform plate.

- Rigid fixation is achieved with plates and screws.

Facial bipartition

- This procedure is well-suited to treat an inverted V deformity of maxillary occlusion.

- Orbital osteotomies leave the floor in continuity with the maxilla.

- Osteotomy through the midincisor line allows medial rotation/transposition.

- An occlusal splint ensures proper positioning of the maxilla.

- Rigid fixation, augmented with bone graft, holds the reduction.

Medial canthopexy

- Osteotomies usually result in detachment of the medial canthal ligament.

- If not reattached, canthal drift gives the appearance of recurrence of the hypertelorism.

Encephaloceles

- Caused by herniation of brain or its lining through a skull defect.

- Frontal skeletal defects can result from Tessier clefts 10, 13 and 14.

- Clinically, they are soft, pulsatile, compressible masses.

- They may transilluminate and have a positive Furstenberg’s sign.

- This is pulsation or expansion of the mass with crying or straining.

- Encephaloceles are classified by their composition into:

- Meningoceles – contain meninges

- Meningoencephaloceles – contain meninges and brain

- Cystoceles – contain meninges, brain and a portion of ventricle

- Myeloceles – contain a portion of spinal cord.

- Meningoceles – contain meninges

- Differential diagnosis includes teratomas, gliomas and dermoids.

- Principles of treatment include:

- Surgical planning aided by ultrasound (US), X-ray, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Multidisciplinary surgical team for a combined intra- and extra-cranial approach.

- Incision of the sac.

- Amputation of excess tissue to the level of the surrounding skull.

- Dural closure.

- Bony reconstruction.

- Skin closure.

- Surgical planning aided by ultrasound (US), X-ray, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- The remaining intracranial brain tissue should be imaged for abnormalities.

Synostosis

- Premature fusion of one or more sutures in the cranial vault or skull base.

- Occurs approximately once in every 2500 live births.

- May occur:

- As an isolated abnormality or

- As part of a syndrome.

- As an isolated abnormality or

- Nonsyndromal synostosis accounts for 90% of cases.

- Most synostosis syndromes are autosomal dominant.

- The often-cited exception – Carpenter’s syndrome – is autosomal recessive.

- Genetic mutations can be identified in:

- 70% of patients with Crouzon’s, Pfeiffer’s or Saethre–Chotzen syndrome.

- Almost 100% of patients with Apert’s syndrome.

- 70% of patients with Crouzon’s, Pfeiffer’s or Saethre–Chotzen syndrome.

- Craniosynostosis begins during pregnancy or the first year of life.

- Usually complete by 3 years.

Aetiology

- Three theories have been proposed:

- Virchow suggested a primary sutural abnormality.

- McCarthy suggested a dural abnormality.

- Moss suggested abnormality in the skull base.

- Virchow suggested a primary sutural abnormality.

- Many synostotic syndromes may be caused by gene mutations in MSX2, TWIST and fibroblast growth factor receptors 1, 2 and 3 (FGFRs).

- Many craniosynostosis syndromes have associated limb abnormalities.

- Craniofacial and limb development may share common molecular pathways.

Classification

- Synostosis is classified according to:

- The location of the affected suture or sutures.

- The resultant head shape.

- The location of the affected suture or sutures.

- The sagittal suture is the most common single suture synostosis (40–60%).

- It has a male preponderance of 4:1.

- Virchow’s law states that skull growth occurs parallel to a synostosed suture.

- Each pattern of fusion therefore results in a characteristic skull shape:

- Sagittal suture: an elongated keel-shaped skull (scaphocephaly or dolichocephaly).

- One coronal suture: a twisted skull (plagiocephaly).

- Both coronal sutures: a short skull anteroposteriorly (AP) (brachycephaly).

- Compensatory growth may occur upwards (turricephaly, oxycephaly or acrocephaly).

- Metopic suture: a triangular-shaped skull (trigonocephaly).

- One lambdoid suture: a twisted skull (posterior plagiocephaly).

- Both lambdoid sutures: a short skull (brachycephaly).

- Synostosis of multiple sutures leads to a cloverleaf-shaped skull (Kleeblattschädel or triphyllocephaly).

- In Greek, dolichos is long; scaphos is boat; plagios is oblique; brachys is short; acros is high; oxys is sharp; trigonos is triangular; triphyllos is trefoil or three leaves.

- In Latin, turris is tall.

- In German, Kleeblattschädel is cloverleaf skull.

- Sagittal suture: an elongated keel-shaped skull (scaphocephaly or dolichocephaly).

Clinical features

- The most striking feature is abnormal skull shape.

- Because the face is attached to the cranial base, synostosis may limit or distort growth of the face and affect occlusal plane symmetry.

- Midface hypoplasia can lead to obstructive sleep apnoea, requiring continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) therapy.

- Bicoronal synostosis may result in recession of the fronto-orbital rim.

- Can lead to exorbitism and exposure keratitis.

- Exorbitism is protrusion of the eyeball due to decreased volume of the bony orbit.

- This is different from exophthalmos, which is protrusion of the eyeball due to an increased volume of orbital contents in a normal bony orbit.

- Exorbitism is protrusion of the eyeball due to decreased volume of the bony orbit.

- Can lead to exorbitism and exposure keratitis.

- Patients may show signs and symptoms of raised intracranial pressure (ICP), including:

- Irritability/headaches

- Vomiting

- Tense fontanelles

- Papilloedema

- Developmental delay

- Seizures.

- Irritability/headaches

- Long-term problems of untreated raised ICP include:

- Blindness

- Intellectual disability.

- Blindness

- Incidence of raised ICP increases proportionately with the number of involved sutures:

- Approximately 14% with single suture synostosis.

- Approximately 47% with multiple suture synostosis.

- Approximately 14% with single suture synostosis.

- Normal ICP values in children are arbitrarily set:

- <10 mmHg is considered normal.

- 10–15 mmHg is considered borderline.

- >15 mmHg is considered high.

- <10 mmHg is considered normal.

- Plotting head circumference on a growth chart can help differentiate synostosis from primary microcephaly or hydrocephalus.

- The cranial index (CI) is the ratio of maximum cranial width to maximum cranial length.

- Children with isolated sagittal synostosis typically have CIs of 60–67%.

- Children with normal head shape typically have CIs of 76–78%.

- Children with isolated coronal synostosis typically have CIs of 84–91%.

- CI is not a diagnostic measure but helps quantify the difference between pre- and post-operative head shape.

- The cranial index (CI) is the ratio of maximum cranial width to maximum cranial length.

Radiological features

- Include primary changes in the suture and secondary changes due to abnormal skull growth.

- Primary changes include:

- Loss of suture lucency

- Loss of sutural interdigitations

- Sclerosis of the suture

- Raising (lipping) of the suture.

- Loss of suture lucency

- Secondary changes include:

- Abnormal skull shape

- Harlequin appearance of the lateral orbit on AP films.

- Caused by superior displacement of the lesser wing of sphenoid.

- Copper-beaten appearance of the skull (a sign of raised ICP).

- Widening of the adjacent sutures in compensation.

- Abnormal skull shape

- CT allows direct visualisation of each suture.

- MRI is not used routinely.

- In syndromic cases, it can rule out cerebellar tonsillar herniation (Arnold–Chiari malformation), which may limit compensatory diversion of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in raised ICP.

Positional plagiocephaly

- True plagiocephaly is caused by unilateral synostosis of the coronal or lambdoid sutures.

- Positional plagiocephaly is distortion of the skull due to external pressure.

- Incidence of positional plagiocephaly has increased in recent years due to the ‘Back to Sleep’ campaign, which recommends nursing babies supine to reduce the risk of cot death.

- Positional plagiocephaly should be managed nonoperatively, as it is usually self-correcting:

- ‘Active repositioning’ into the prone position during waking hours.

- Special orthotic helmets are commercially available to help remodel the skull.

- Physiotherapy may be required to treat an underlying cause, such as torticollis.

- ‘Active repositioning’ into the prone position during waking hours.

- Clinical features that differentiate positional from true plagiocephaly include:

- Skull shape

- The skull is rhomboid shaped in positional plagiocephaly.

- The occiput is flattened by external pressure, which pushes the ear and forehead forward on that side.

- In true plagiocephaly, one side of the skull does not grow adequately in an AP direction due to synostosis.

- This produces a triangular-shaped skull.

- The base of the triangle lies on the unaffected side.

- The apex of the triangle lies on the affected side, as if pinched at the site of synostosis.

- This produces a triangular-shaped skull.

- The skull is rhomboid shaped in positional plagiocephaly.

- Ear position

- In true plagiocephaly, the distance between the lateral orbit and the ear is asymmetrical.

- Brow shape

- The brow has an ipsilateral prominence in positional plagiocephaly.

- It has a contralateral prominence in true plagiocephaly.

- The brow has an ipsilateral prominence in positional plagiocephaly.

- Cheek position

- The ipsilateral cheek is prominent in positional plagiocephaly.

- Skull shape

Syndromal synostosis

- Synostosis is a feature of over 100 syndromes.

- The more common syndromes share many features:

- Midface hypoplasia

- Skull base growth abnormalities

- Abnormal facies

- Limb abnormalities.

- Midface hypoplasia

Apert’s syndrome

- Occurs once in 160,000 live births.

- Most cases are sporadic but can be autosomal dominant.

- Clinical features:

- Bicoronal synostosis

- Exorbitism with hypertelorism

- Downslanting palpebral fissures

- Midface hypoplasia

- Small, beaked nose

- Class III malocclusion

- CP in 20% of cases

- Complex syndactyly of both hands and feet.

- Bicoronal synostosis

- The hand deformity is classified as:

- Type I: little finger and thumb are separate.

- Type II: only the thumb is separate.

- Type III: all fingers are fused and share a common nail.

- Type I: little finger and thumb are separate.

- There may be nonprogressive ventriculomegaly, but hydrocephalus is uncommon.

- Some have delayed mental development, but many develop normal intelligence.

- Conductive hearing loss is common.

- Cardiac and genitourinary abnormalities found in up to 10% of cases.

Crouzon’s syndrome

- Affects one in 25,000 live births.

- Most are autosomal dominant but can occur sporadically.

- Clinical features:

- Bicoronal synostosis, although other sutures may be involved

- Midface hypoplasia with significant exorbitism

- Normal hands

- High palatal arch; occasional CP

- Class III malocclusion

- Conductive hearing loss.

- Bicoronal synostosis, although other sutures may be involved

- Progressive hydrocephalus, often associated with chronic tonsillar herniation.

- In the absence of raised ICP, developmental delay is rare.

Saethre–Chotzen syndrome

- Estimated to affect one in 50,000 live births.

- Caused by mutations in the TWIST gene (autosomal dominant).

- Clinical features:

- Bicoronal synostosis

- Low-set hair line

- Eyelid ptosis

- Small, posteriorly displaced ears with prominent crura

- Partial syndactyly of the second and third digits is often seen.

- Bicoronal synostosis

- Intelligence is usually normal, but some have mild impairment.

Pfeiffer’s syndrome

- Rare; inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

- Craniofacial appearance is similar to that of Apert’s.

- A severe form of Pfeiffer’s is characterised by Kleeblattschädel deformity and profound CNS abnormalities.

- Otherwise, intelligence is usually normal.

- Hallmark feature is broad great toes and thumbs.

Muenke’s syndrome

- Discovered in 1996; also known as FGFR3-associated coronal synostosis.

- Differs from other syndromic synostoses because it is defined by a genetic test (Pro250Arg mutation) rather than a constellation of symptoms and signs.

- Affects one in 30,000 and inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

- Coronal sutures are specifically involved; appearances are otherwise largely normal.

- Hearing loss (30%) and learning difficulties (10%) may occur.

- Reoperation is required more often than with other syndromic synostoses.

Carpenter’s syndrome

- Very rare autosomal recessive condition.

- Various sutures may be involved, commonly sagittal and coronal.

- Intelligence is usually impaired.

- Congenital cardiac abnormalities seen in ⅓ of cases.

- Obesity is typical.

- Clinical features:

- Partial syndactyly of the fingers.

- Preaxial polydactyly of the feet.

- Congenital cardiac abnormalities seen in ⅓ of cases.

Treatment

- Surgery is extensive and potentially risky, associated with significant blood loss.

- Regarded as safe if performed by specialist teams in established centres.

- Main aims of surgery:

- Protect the airway and corneas

- Prevent progressive deformity

- Correct established deformity

- Reduce risks to function from raised ICP.

- Protect the airway and corneas

- Advantages of operating in infancy include:

- Harnessing the most ‘brain push’ to remodel the calvarium during infancy.

- Postsurgical defects ossify more completely before 9–10 months.

- Infantile calvarium is more malleable.

- Harnessing the most ‘brain push’ to remodel the calvarium during infancy.

- However, operating too early can lead to excessive blood loss and difficulties with fixation because the bone is too soft.

- Shunting procedures to treat progressive hydrocephalus are usually done prior to bony remodelling.

- Were both procedures carried out simultaneously, shunting would reduce brain size while vault remodelling would increase skull size.

- The resulting dead space would allow haematoma to collect.

- Were both procedures carried out simultaneously, shunting would reduce brain size while vault remodelling would increase skull size.

- Surgical techniques include:

Sagittal strip craniectomy

- A longitudinal strip of bone over the suture is excised.

Fronto-orbital advancement and anterior cranial vault reconstruction

- The fronto-orbital bar is advanced and held with miniplates.

- This increases the AP dimension of the skull.

- Also deepens the upper orbits, improving exorbitism.

- This increases the AP dimension of the skull.

- The remaining frontal bone is sectioned and replaced in the desired shape.

Posterior cranial vault reconstruction

- Distraction osteogenesis is being used more frequently, given the higher incidence of severe bleeding with posterior vault remodelling.

Le Fort III osteotomy

- Performed to correct midface retrusion encountered in syndromal synostosis.

- May be performed early, aiming to become independent of tracheostomy or ameliorate severe obstructive sleep apnoea.

Monobloc advancement

- Advances the fronto-orbital and Le Fort III segments as one block.

- Associated with higher infection rates and greater blood loss, likely due to communication between cranial and nasal cavities.

Le Fort I osteotomy

- Addresses class III malocclusion and anterior open bite, commonly seen with midface hypoplasia.

- Planned to coincide with completion of orthodontic treatment, at the time of skeletal maturity.

Skeletal distraction

- Many skeletal manipulations are now done by distraction, including:

- Le Fort I

- Posterior cranial vault

- Le Fort III

- Monobloc

- Mandible.

- Le Fort I

- Osteotomies are made as usual.

- A distraction device is fitted either internally or externally.

- As the bone is distracted, the soft tissues are gradually stretched over several weeks.

- Greater advancement can be achieved with distraction than by single-stage advancement.

- Once the desired advancement is achieved, further surgery may be required to stabilise the bones with plates and screws.

- If not, a prolonged period of consolidation is required with the distractor in place.

Post-operative care

- Monitoring of haemodynamic stability and conscious level on a paediatric intensive care unit is required for 24–48 hours.

- A significant amount of swelling is expected.

- Pyrexia of 38 °C for the first 72 hours is not unusual.

Complications

- Overall mortality reported as 1–2% in specialist units.

- Low risk of infection, dehiscence, meningitis, dural tears with CSF leak, air embolus, cerebral oedema and life-threatening bleeding.

- Coagulopathy is most commonly precipitated by massive blood transfusion and low body temperature.

- There may be persisting asymmetry, contour irregularities or incomplete ossification.

Atrophy–hypoplasia

- This group includes:

- Hemifacial microsomia

- Treacher Collins syndrome

- Nager’s syndrome

- Binder’s syndrome

- PRS

- Hemifacial atrophy

- Radiation-induced atrophy–hypoplasia.

- Hemifacial microsomia

- Many of these conditions could be classified as clefts due to the predictable lines of hypoplasia seen in some Tessier clefts.

Hemifacial microsomia

- Congenital condition with a variable phenotype, characterised by underdevelopment of one side of the face. Also known as:

- First and second branchial arch syndrome.

- Otomandibular dysostosis.

- First and second branchial arch syndrome.

- Correlates with a Tessier 7 cleft.

- Hemifacial microsomia is relatively common, affecting one in 4000 live births.

- Unlike Treacher Collins syndrome, it is not usually inherited and is typically asymmetrical.

- It may arise due to haemorrhage from an abnormal stapedial artery.

- Clinical features:

- Underdevelopment of the external and middle ear.

- Underdevelopment of the mandible, zygoma, maxilla, temporal bone, facial muscles, muscles of mastication, palatal muscles, tongue and parotid gland.

- Macrostomia, a first branchial cleft sinus and possible cranial nerve involvement.

- Underdevelopment of the external and middle ear.

- Goldenhar syndrome is a variant of hemifacial microsomia but is typically bilateral, associated with epibulbar dermoids and vertebral abnormalities.

Classification

- The following classifications of hemifacial microsomia have been described:

- OMENS classification

- This classifies deformities of the Orbits, Mandible, Ear, Facial Nerve and Soft tissue.

- Pruzansky classification of the mandible:

- Type I: mild ramus hypoplasia, the body is minimally affected.

- Type IIa: ramus and condyle hypoplasia, but the glenoid–condyle relationship is maintained.

- Type IIb: as for type IIa but with a nonarticulating temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

- Type III: the ramus is very thin or absent with no evidence of a TMJ.

- Mulliken and Kaban subdivided Pruzansky type II as shown.

- Type I: mild ramus hypoplasia, the body is minimally affected.

- Meurman classification of the ear:

- Grade I: small, malformed auricle, but all components present.

- Grade II: vertical remnant of cartilage and skin; atresia of the external meatus.

- Grade III: total or near-total absence of the auricle.

- Grade I: small, malformed auricle, but all components present.

- SAT classification

- Proposed by David, it is analogous to the TNM system used in cancer staging.

- It grades the Skeletal, Auricular and soft Tissue anomalies and suggests a treatment plan.

- Proposed by David, it is analogous to the TNM system used in cancer staging.

Treatment

- Should be individualised to the patient.

- Abnormalities in other organ systems should be sought.

- The following is a general guide:

Before 2 years

- Remove any auricular appendages.

- Correct macrostomia with a commissuroplasty.

- Fit hearing aids.

- Occasional involvement of the fronto-orbital region may require fronto-orbital advancement.

Between 2 and 6 years

- Distraction of the mandibular ramus.

- Pruzansky III deformities may require formal reconstruction of the mandibular ramus.

- This is usually performed with a costochondral rib graft.

Between 6 and 14 years

- Orthodontic treatment.

- Ear reconstruction.

- Soft tissue augmentation:

- Free tissue transfer

- Fat grafting.

- Free tissue transfer

After 14 years

- Augmentation of deficient areas of the facial skeleton.

- Can be done using bone grafts or alloplastic implants, e.g. Medpor®.

- Orthognathic surgery (OGS).

Treacher Collins syndrome

- Also known as:

- Franceschetti syndrome.

- Mandibulofacial dysostosis.

- Tessier 6,7,8 cleft.

- Franceschetti syndrome.

- Autosomal dominant with variable expressivity.

- Affects between one in 25,000 and one in 50,000 live births; equal sex distribution.

Clinical features

- Bilateral symmetrical abnormalities of the first and second branchial arches.

- Characteristic convex facial profile.

- Prominent nasal dorsum and retrusive lower jaw and chin.

- Average or above-average intelligence is the norm.

- Typically, abnormalities are present in the following sites:

Eyes

- Part of the lateral canthus and lower eyelid may be absent (coloboma).

- Eyelashes are often absent medially.

- Atrophic tarsal plate.

- Medially displaced lateral canthus.

- Absent lacrimal apparatus.

- Antimongoloid slant of the palpebral fissure.

- Hypoplastic lateral orbits.

Nose

- Moderately wide bridge with mid-dorsal hump.

- Drooped tip that lacks projection.

Cheek

- The zygoma may be hypoplastic, clefted through the arch or absent.

- A depression may run between the corner of the mouth and angle of the mandible, along the line of a Tessier 7 cleft.

Palate

- CP, with or without CL, occurs in 30% of cases.

- There may be associated choanal atresia.

- If not, the palate is usually high-arched.

Maxilla and mandible

- The ramus of the mandible is often short.

- TMJ and muscles of mastication may be hypoplastic or absent.

- Class II malocclusion with anterior open bite.

Ear

- May be small (microtia) or buried under the skin (cryptotia).

- External meatus may be hypoplastic.

- Middle ear deformities include missing ossicles or cavities.

Cranium

- Reduced cranial base angle (basilar kyphosis).

- Although synostosis is not a feature, the skull may have abnormally short AP length and bitemporal width.

Treatment

Airway

- Patients often have difficulty maintaining their airway due to maxillary and mandibular hypoplasia.

- Tracheostomy may be required.

- Nursing them in a prone position can help improve their oxygen saturation.

- Increased risk of airway obstruction following CP repair.

Feeding

- Factors affecting the airway can also affect swallowing and feeding.

- Failure to thrive requires supplemental tube feeding.

Zygoma and orbit

- Calvarial bone graft can be used to augment the orbital floor and zygoma.

- Lateral canthopexy is done through the same bicoronal incision.

- Usually performed when the child is >7 years, when bony development in that region is almost complete.

Mandible

- Mandibular deformity may be corrected with:

- Rib grafts

- Mandibular advancement

- Bimaxillary procedures

- Le Fort I osteotomy and orthodontic treatment

- Distraction

- Genioplasty

- TMJ reconstruction with costochondral graft (Pruzansky III).

- Rib grafts

- Usually performed at early skeletal maturity, between 13 and 16 years.

Ear

- Reconstruction of the external ear may be required.

- Middle ear surgery is postponed until after auricular reconstruction, to preserve soft tissues.

- Hearing deficits can be improved with hearing aids.

Nose

- Rhinoplasty involves:

- Open approach

- Osteotomies

- Dorsal hump reduction

- Cephalic trim of the lower lateral cartilages

- Columella strut to improve tip projection.

- Open approach

- This is done following any OGS.

Nager’s syndrome

- Also known as acrofacial dysostosis.

- Rare; inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.

- Craniofacial features are similar to Treacher Collins syndrome.

- CP is almost universal.

- There is associated thumb and radial hypoplasia.

- Intelligence is usually impaired.

Binder’s syndrome

- Also known as maxillonasal dysplasia.

- May be inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.

- Clinical features:

- Short nose with flat bridge and short columella

- Absent frontonasal angle

- Absent anterior nasal spine

- Perialar flattening

- Convex upper lip

- Tendency to class III malocclusion.

- May be inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.

Pierre Robin sequence (PRS)

- Affects approximately one in 8500 live births and consists of:

- Micrognathia

- Glossoptosis

- CP.

- Micrognathia

- Due to a small jaw, the tongue occupies a greater proportion of the oropharynx.

- Severe respiratory obstruction can result from the tongue falling backwards (glossoptosis).

- The combined effort of feeding and maintaining the airway is tiring.

- This leads to faltering growth or failure to thrive.

- Most babies have outgrown these difficulties by 6 months, due to mandibular growth and improved neuromuscular control of the tongue.

- Reports suggest underlying genetic mutations in SOX9 and KCNJ2.

Treatment

- Immediate life-saving airway management involves turning the newborn prone to relieve glossoptosis.

- If unsuccessful, a nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) can be inserted to bypass the obstruction caused by the tongue.

- PRS has been classified by severity by the Cleft service at Birmingham Children’s Hospital, UK.

- This classification is also used to guide treatment:

- Grade 1: Nursed side-to-side only.

- Grade 2: Requires nasogastric (NG) feeding and nursed side-to-side.

- Grade 3: Requires NPA, NG feeding and nursed side-to-side.

- Grade 1: Nursed side-to-side only.

- Once stabilised and gaining weight, all PRS babies are discharged with an oxygen saturation monitor.

- A cleft specialist nurse closely monitors weight gain.

- Parents and other carers are trained to manage NG feeds and the NPA.

- Also trained in Paediatric Basic Life Support prior to discharge.

- Birmingham Children’s Hospital successfully treats all PRS babies this way.

- Other more invasive treatments include:

- Glossopexy (tongue–lip adhesion)

- Tracheostomy

- Subperiosteal release of the floor of the mouth

- Distraction osteogenesis of the mandible

- Distraction osteogenesis carries a low but quantifiable mortality rate.

- Distraction osteogenesis of the mandible

- Glossopexy (tongue–lip adhesion)

- Some surgeons maintain that a proportion of severely affected PRS babies require surgical intervention, but that view is controversial.

- PRS may present with other syndromes and anomalies.

- All PRS babies should be screened for Stickler’s syndrome.

- There is a risk of retinal detachment, preventable by early intervention.

- All PRS babies should be screened for Stickler’s syndrome.

Progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)

- Acquired condition also known as Parry–Romberg syndrome.

- Usually unilateral; 5% of cases are bilateral.

- Occurs sporadically and not associated with a family history.

- Aetiology is unknown; may be due to viral infection, trigeminal peripheral neuritis or an abnormality in the cervical sympathetic nervous system.

- Presents similar to linear scleroderma in early stages.

Clinical features

- Characterised by gradual wasting of one side of the face and forehead.

- Usually starts between 5 years and late teens.

- Female to male ratio is 1.5:1.

- Involves skin, soft tissue and bone.

- Muscle involvement can also include atrophy of the tongue and palate.

- Typically progresses within the dermatome of one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve.

- Wasting continues for a number of years before gradually stopping.

- The result is permanent tissue deficiency on one side of the face.

- The following may be seen:

- Localised atrophy of the skin with pigment changes

- Change of hair colour or alopecia

- Change of iris colour and enophthalmos

- A sharp depression on the forehead, occasionally extending into the hairline

- This early sign is known as ‘coup de sabre’

- Atrophy of cheek bone and soft tissue

- Malocclusion.

- Localised atrophy of the skin with pigment changes

Treatment

- Generally, no treatment is performed while the condition is active and progressive.

- Short-term improvements may be achieved with injectable fillers.

- Reconstruction is performed once the condition has been stable for about 12 months.

- This is judged by serial photographs.

- Reconstructive options include:

- Fat and dermofat grafts

- Cartilage grafts

- Le Fort I osteotomy

- Genioplasty

- Alloplastic augmentation

- Temporoparietal fascia and temporalis muscle transfers

- Free tissue transfer.

- Adipofascial flaps are preferred over muscle flaps due to the atrophy of muscle over time.

- Alloplastic augmentation

- Fat and dermofat grafts

Radiation-induced atrophy–hypoplasia

- High dose radiation is used to treat some childhood tumours.

- Deformity may arise by the following mechanisms:

- Impaired growth as the sphenoid ‘locks in’ the upper face.

- The frontal, ethmoid and maxillary sinuses fail to expand.

- Impaired growth as the sphenoid ‘locks in’ the upper face.

- Reconstruction usually involves a combined craniofacial approach:

- Craniotomy to reposition the skull base, orbit and maxilla

- Orbital expansion and mandibular lengthening

- Bone grafts (inlay rather than onlay)

- Free tissue transfer to augment the soft tissues.

- Craniotomy to reposition the skull base, orbit and maxilla

Neoplasia–hyperplasia

Fibrous dysplasia

- Rare, non-neoplastic benign bone disease.

- Lesions are osseous rather than fibrous, characterised by abnormal proliferation of bone-forming mesenchyme.

- Bone maturation stalls at the woven bone stage.

- Usually presents as an enlarging mass in the maxilla or mandible.

- Mass effect can cause cranial nerve compression, proptosis and malocclusion.

- Malignant transformation occurs in 0.5% of patients.

- The condition is usually progressive until about 30 years.

- Diagnosis is confirmed on bone biopsy.

Classification

- Monostotic, with single bone involvement.

- Craniofacially, it usually affects frontal bone, sphenoid or maxilla.

- Can also affect ribs, femur or tibia.

- Craniofacially, it usually affects frontal bone, sphenoid or maxilla.

- Polyostotic, with multiple bone involvement.

- Approximately 3% have the triad of McCune–Albright syndrome:

- Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia

- Precocious puberty

- Café-au-lait macules.

- Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia

- Approximately 3% have the triad of McCune–Albright syndrome:

- Hyperthyroidism and tumours of the pituitary gland may also be found.

- Cherubism is a rare autosomal dominant condition, also known as familial fibrous dysplasia.

- Characterised by multiple areas of fibrous dysplasia within the mandible and maxilla.

- Self-limiting and regresses spontaneously, leaving no deformity.

- Characterised by multiple areas of fibrous dysplasia within the mandible and maxilla.

Treatment

- Early intervention is required when function is at risk:

- Optic nerve compression or other nerve palsies

- Diplopia

- Malocclusion.

- Surgery involves resection of the abnormal areas.

- The resultant defects can be reconstructed with calvarial bone grafts or alloplastic implants.

- Free tissue transfer is used to fill postresection dead space.

- Some cases have responded to bisphosphonate therapy.

- Optic nerve compression or other nerve palsies

Neurofibromatosis

- A group of genetic disorders that predispose to development of Schwann cell tumours.

- Inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with variable penetrance.

- 50% of new cases arise from spontaneous mutations with no family history.

Classification

- Many types have been described; only two forms are commonly encountered:

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)

- Also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease.

- The most common type (90%), affecting one in 3000 births.

- The mutated gene is on chromosome 17.

- Two of the following clinical features are required for diagnosis:

- Six or more café-au-lait macules (>0.5 cm in children; >1.5 cm in adults)

- Two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Axillary or inguinal freckling

- Optic glioma

- Two or more Lisch nodules (hamartomas of the iris)

- A distinctive osseous lesion with cortical thinning or dysplasia

- A first-degree relative with NF1.

- Six or more café-au-lait macules (>0.5 cm in children; >1.5 cm in adults)

- NF1 is associated with orthopaedic complications, including:

- Scoliosis or kyphosis of the spine

- Congenital bowing and pseudarthrosis of the tibia and forearm.

- Scoliosis or kyphosis of the spine

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2)

- Also known as central neurofibromatosis.

- Affects approximately one in 25,000 live births.

- The mutated gene is on chromosome 22.

- Characterised by bilateral vestibular schwannomas.

- Other abnormalities include:

- Intracranial meningiomas

- Spinal tumours (usually schwannomas or meningiomas)

- Peripheral nerve schwannomas

- Ocular abnormalities (posterior subcapsular lenticular opacities).

- Intracranial meningiomas

Malignancy

- Lifetime risk of malignant transformation is <10%.

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNST) arise from Schwann cells.

- Usually occur in plexiform neurofibromas.

- Pain and rapid growth are indicators of malignant degeneration.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can help localise the malignancy.

- Metastases are common.

- An aggressive surgical attempt at total excision is undertaken.

- 5-year survival following MPNST is approximately 16–52%.

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNST) arise from Schwann cells.

Treatment

- Treatment of plexiform neurofibromas requires a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach.

- Trials are underway looking at imatinib for treatment of plexiform neurofibromas.

- However, surgery is currently the mainstay of treatment.

- The following should be considered:

- Timing and extent of surgery

- Strategies to deal with bleeding refractory to conventional electrocautery:

- Hypotensive anaesthesia, invasive monitoring and cell salvage

- Some advocate packing the wounds open with direct compression.

- Delayed closure then takes place after 48 hours.

- Hypotensive anaesthesia, invasive monitoring and cell salvage

- Timing and extent of surgery

- There is a balance between an acceptable aesthetic outcome and preserving function.

- The limits of surgery should be discussed with the patient.

- Surgery addresses the deformity only; recurrence is usual.

- Improvements are temporary because skin involved with neurofibroma lacks elasticity.

- Specific craniofacial problems associated with NF1 include:

Orbitopalpebral neurofibromas

- Associated with dysplasia of the sphenoid wing.

- Allows the temporal lobe to herniate into the orbit.

- The bony orbit is enlarged, with pulsatile exophthalmos.

- If vision is preserved in the affected eye, the neurofibroma is debulked.

- The orbit can be approached through:

- The upper eyelid for mild lesions

- A bicoronal skin incision with osteotomy into the lateral orbit

- A combined craniofacial approach with frontal craniotomy.

- The upper eyelid for mild lesions

- The sphenoid wing is reconstructed using split rib or calvarial bone graft.

- If vision is impaired, orbital exenteration is performed.

- The eyelid is used for skin cover to allow the orbit to take a prosthesis.

Plexiform neurofibromas of the facial soft tissues

- Cause distortion of the facial soft tissues and skeleton.

- Deformities can lead to visual loss.

- Bony defects are tackled first, with correction of the occlusal plane.

- Soft tissues are reconstructed with free tissue transfer or dermal-fascial-fat grafts.

- Tissue redundancy is addressed through a facelift incision or Weber–Ferguson approach.

- Techniques to minimise recurrence of soft tissue ptosis include:

- Anchoring tissue to bone

- Fascia lata slings.

- Techniques to minimise recurrence of soft tissue ptosis include:

Unclassified craniofacial abnormalities

- These include organ-specific abnormalities:

- Anophthalmia

- Choanal atresia

- Anotia.

- Anophthalmia

Congenital dermoid cysts

- Commonly located in the superolateral orbit, orbital rim and forehead.

- Represent displacement of dermal and epidermal cells into embryonic lines of fusion.

- They differ from inclusion cysts by the presence of dermis and skin adnexa.

- Complete surgical excision is the only effective treatment.

- Can be excised through a supratarsal incision on the upper eyelid.

- Dissection proceeds through the orbicularis oculi onto the cyst.

- Often located deep to periosteum.

- Dissection proceeds through the orbicularis oculi onto the cyst.

Nasal dermoid cysts

- Approximately 10% of dermoids are located on the nose.

- Have a different origin to other dermoids and warrant investigation.

Embryology

- Frontal and nasal bones are separated by a small fontanelle – the fonticulus nasofrontalis.

- A prenasal space exists between the skull base and nasal tip.

- Dura extends through the fonticulus into the prenasal space, where it contacts skin.

- With facial growth, the dura separates from the skin and recedes.

- At this time, the fonticulus nasofrontalis and foramen cecum fuse, forming the cribriform plate.

- Nasal dermoids and sinuses are formed when the dura fails to separate from skin.

- As the dura retracts intracranially, it pulls ectodermal tissue with it.

- Nasal or midline dermoids should be imaged to rule out intracranial extension.

- CT may show a bifid crista galli and patent foramen cecum.

- MRI further demonstrates the extent of intracranial involvement.

- CT may show a bifid crista galli and patent foramen cecum.

Treatment

- A combined craniofacial approach with a neurosurgeon.

- The entire cyst can sometimes be removed through a frontal craniotomy.

- Alternatively, it can be approached by direct incision around the cyst or open rhinoplasty.

- The stalk is traced superiorly, between the cartilaginous septum and nasal bones.

- If the stalk is not excised, craniotomy is required to ensure complete removal.

- Incomplete excision can lead to infection and osteomyelitis.

- The stalk is traced superiorly, between the cartilaginous septum and nasal bones.

Cleft lip; cleft lip and palate

Cleft lip (CL)

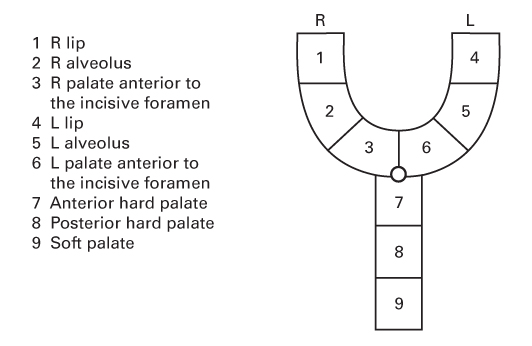

- CL is a congenital abnormality of the primary palate.

- The primary palate lies anterior to the incisive foramen and consists of:

- The lip

- The alveolus

- The hard palate anterior to the incisive foramen.

- The primary palate lies anterior to the incisive foramen and consists of:

Cleft palate (CP)

- CP is a congenital abnormality of the secondary palate.

- The secondary palate lies posterior to the incisive foramen and consists of:

- The hard palate posterior to the incisive foramen

- The soft palate.

- The hard palate posterior to the incisive foramen

- Isolated CP is embryologically and aetiologically distinct from CL and CL&P.

Cleft lip and cleft palate

- Both CL and CP may be:

- Complete or incomplete

- Unilateral or bilateral.

- Complete or incomplete

- Unilateral CP occurs when the vomer remains attached to one palatal shelf.

- Bilateral CP occurs when the vomer is attached to neither palatal shelf.

- In isolated CP, the vomer tends to be high and hypoplastic.

Epidemiology

- Incidence of CL&P varies according to the study population.

- In the United Kingdom, CL, CL&P and CP occur once in 700 live births.

- In Caucasians, CL ± CP occur once in 1000 live births.

- In Asia, the incidence is higher: once in 500 live births.

- In Africa, the incidence is lower: once in 2500 live births.

- In the United Kingdom, CL, CL&P and CP occur once in 700 live births.

- Combined CL&P is most common, seen in 50% of cases.

- Isolated CP occurs in 30% of cases.

- Isolated CL occurs in 20% of cases.

- Isolated CP occurs in 30% of cases.

- The ratio of left:right:bilateral CL is 6:3:1.

CL and CL&P

- Twice as common in males.

- Has a familial association.

- The relative risk of a child having CL or CL&P is:

- 0.1% if there is no history of CL or CL&P in the family

- 4% if there is one affected sibling

- 7% if there is one affected parent

- 9% if there are two affected siblings

- 17% if one parent and one sibling are affected.

- 9% if there are two affected siblings

- 0.1% if there is no history of CL or CL&P in the family

- Only 10% of CL and CL&P cases are associated with other abnormalities.

- Van der Woude syndrome is one of the few syndromes associated with CL.

- 1–2% of CL and CL&P patients are affected.

- It has the following characteristics:

- Autosomal dominance

- Lower lip pits

- Absence of second premolar teeth.

- Autosomal dominance

- 1–2% of CL and CL&P patients are affected.

- Environmental teratogens associated with CL and CL&P include:

- Intrauterine exposure to phenytoin (10-fold increased incidence)

- Maternal smoking (twofold increased incidence)

- Maternal diabetes

- Excessive maternal alcohol consumption

- Other anticonvulsants

- Retinoic acid and its derivatives.

- Intrauterine exposure to phenytoin (10-fold increased incidence)

- These are associated, not causal, factors.

- Some studies show that maternal folic acid supplementation produces a lower rate of cleft deformities than predicted.

Isolated CP

- Twice as common in females.

- Fairly consistent worldwide incidence: once in 2000 births.

- Occurs in association with other abnormalities or syndromes in up to 70% of cases.

- Nonsyndromal CP may be associated with the environmental teratogens previously mentioned.

Mechanism

- CL is thought to be caused by either:

- Failure of fusion between the medial nasal process and maxillary process or

- Failure of mesodermal penetration into the layer between ectoderm and endoderm.

- This leads to breakdown of the processes after they have initially fused.

- Failure of fusion between the medial nasal process and maxillary process or

Anatomy

- Complete unilateral CL deformity is characterised by:

- Discontinuity in the skin and soft tissue of the upper lip.

- Vertical and transverse soft tissue deficiency on the cleft side.

- Abnormal attachment of lip muscles into the alar base and nasal spine.

- Outwardly rotated and prominent premaxilla.

- Retropositioned and hypoplastic lateral maxillary element.

- Cleft in the alveolus, usually found at the site of future canine tooth eruption.

- Defect in the hard palate anterior to the incisive foramen.

- Nasal deformity.

- Defect in the hard palate anterior to the incisive foramen.

- Discontinuity in the skin and soft tissue of the upper lip.

Incomplete CL

- CL is incomplete when the cleft does not involve the full height of the lip.

- The nostril sill will therefore be intact.

- Forme fruste, or microform cleft, is a mild form of incomplete CL.

- One or more of the following features may be present in a forme fruste:

- A notch in the vermilion

- A vertical fibrous band from the wet–dry vermilion border (the red line) to the nostril floor

- A kink in the nasal ala on the same side.

- A notch in the vermilion

- Simonart’s band is a soft tissue bridge lying across an otherwise complete CL and alveolus.

- There is no consensus definition; the etymology is interesting.

- Simonart’s band does not convert a complete CL into an incomplete CL.

- There is no consensus definition; the etymology is interesting.

Anatomy of the unilateral CL nasal deformity

- The nasal deformity associated with CL includes:

- Deviation of the nasal spine, columella and caudal septum away from the cleft side.

- Dislocation of the inferior edge of the septum out of the vomer groove.

- Separation of the domes of the alar cartilages at the nasal tip.

- Dislocation of the upper lateral nasal cartilage from the lower lateral cartilage on the cleft side.

- Sagging of the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage on the cleft side.

- Retroposition of the alar base on the cleft side.

- Deficient vestibular lining on the cleft side.

- Flattening and displacement of the nasal bone on the cleft side.

- Deviation of the nasal spine, columella and caudal septum away from the cleft side.

Classification

- Popular classification systems include:

Descriptive

- A ‘say-what-you-see’ classification, such as ‘left unilateral complete CL’.

- Can include a schematic diagram showing the relative width and extent of the cleft.

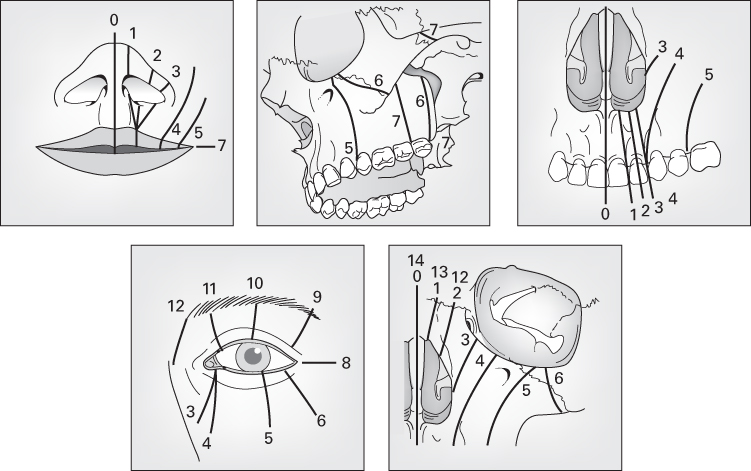

Kernahan’s striped ‘Y’

- A graphical classification, likening the CL&P deformity to the letter ‘Y’.

- Centred on the incisive foramen, dividing primary from secondary palate.

- Each anatomical area is allocated an area on the Y.

- Stippling of a box indicates a cleft.

- Stippling of half a box indicates an incomplete cleft.

- Cross-hatching indicates a submucous cleft.

- The original has been modified by many, including Millard, Jackson and Schwartz, to represent submucous clefts, Simonart’s bands and the nasal deformity.

LAHSHAL

- Otto Kriens described this palindromic acronym for clefts.

- Represents the Lip, Alveolus, Hard palate and Soft palate.

- The letters read from the patient’s right to left.

- The second H is sometimes omitted for simplicity.

- Upper case letters represent complete clefts.

- Lower case letters represent incomplete clefts.

- No cleft is represented with a dot.

- An asterisk represents a microform cleft.

- For example:

- . . HSH . . is a complete cleft of the secondary palate.

- l . . . . . . is a right-sided incomplete CL.

- LA . . . AL is a bilateral complete CL and alveolus.

- Represents the Lip, Alveolus, Hard palate and Soft palate.

Veau

- Described in 1931; classifies CL&P into four groups:

- I: Defect of the soft palate alone.

- II: Defect of the hard and soft palate (not anterior to the incisive foramen).

- III: Defects involving the palate through to the alveolus.

- IV: Complete bilateral clefts.

- I: Defect of the soft palate alone.

Organisation of cleft services in the United Kingdom

- Historically, CL&P repair was undertaken by surgeons specialising in plastic, maxillofacial, ENT or paediatric surgery.

- In 1996, UK Health Ministers commissioned a study to advise on standards of care for children with CL&P.

- The Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) study findings were published in 1998.

- The results were disappointing:

- Many surgeons operated on fewer than 10 cases per year

- Almost 40% of patients had poor or very poor dental arch relationship

- Only 58% of alveolar bone grafts were successful

- 40% of 5-year-old children were in need of treatment for dental caries

- 10% of 12-year-old children had persistent symptomatic oral fistulas.

- Recommendations were based on ‘good practice’ models from Europe and the United States:

- Primary cleft surgeons should see at least 30 new referrals per year

- Expertise and resources should be concentrated from 57 to 8–15 units.

- Cleft surgeons should have undergone extended CL&P training.

- Cleft teams should participate in multicentre audit and research.

- Record keeping should be standardised and protocolised.

- Both child and family should have access to a range of specialties, including paediatrics, clinical psychology and genetics.

- Currently, England and Wales are served by nine different cleft services or networks.

- Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have their own services or networks.

- A modern cleft team comprises the following members:

- Cleft coordinator

- Plastic surgeon, maxillofacial surgeon and ENT surgeon

- Cleft specialist nurse, speech and language therapist

- Clinical psychologist, clinical geneticist and audiologist

- Paediatrician, paediatric dentist, orthodontist and medical photographer.

- Parents may require support from cleft specialist nurses regarding:

- Explanation of the diagnosis

- Outline of the likely treatment plan

- Help and advice on how to feed a baby with a cleft

- Psychological and emotional support.

- Many surgeons operated on fewer than 10 cases per year

Timing of repair

- Repair was traditionally performed when the child had attained the three ‘10’s:

- Weight >10 lb

- Age >10 weeks

- Haemoglobin >10 g/dl.

- Weight >10 lb

- There is little firm evidence to support the optimum timing of cleft repair.

- There is little to suggest superiority of neonatal repair.

- Palate closure before 8 years affects maxillary growth; closure after this point does not.

- However, the aim of palate repair is to allow acquisition of normal speech by 5 years.

- This is facilitated by palate repair before speech acquisition begins (with babbling) at 8 months.

- However, the aim of palate repair is to allow acquisition of normal speech by 5 years.

- Options include:

Conventional repair

- Lip and anterior palate repaired at 3 months.

- Any remaining cleft in the secondary palate is repaired between 6 and 12 months.

Delaire technique

- Lip and soft palate repaired simultaneously at 6–9 months.

- Remainder of the palate closed at 14–18 months.

- May result in better midface growth, as less palate dissection is required at the second operation.

Schweckendiek technique

- Soft palate repaired at 6–8 months.

- Lip repaired 3 weeks later.

- Repair of hard palate postponed until 11–13 years.

- Excellent midface growth reported because maxillary growth centres are not disturbed.

- However, only 28% of patients achieved normal speech.

Oslo technique

- Lip repaired at 3 months.

- Anterior palate and alveolar region closed with a vomerine flap during lip repair.

- The vomer flap closes the anterior hard palate and nasal floor in continuity with the lip.

- Remaining palate repaired at 18 months with a modified von Langenbeck repair.

- Critics of the vomerine flap claim the scar at the vomeropalatine suture limits maxillary growth.

Adjuncts to surgery

Presurgical orthodontics

- Presurgical orthodontics involves the application of devices, which:

- Narrow the cleft deformity

- Correct alignment of the alveolar processes

- Mould the nasal deformity.

- Narrow the cleft deformity

- Proponents claim that this:

- Makes subsequent surgical repair easier

- Improves outcome, particularly for the nose.

- Makes subsequent surgical repair easier

- There are two main types of presurgical orthodontic appliances:

- Passive appliances

- Include obturators or feeding plates.

- Prevent displacement of the alveolar arch by reducing distorting forces produced by tongue movement.

- Include obturators or feeding plates.

- Dynamic appliances

- Include the Latham appliance.

- This is pinned into the maxilla intraorally and exerts an active force on the cleft deformity.

- Less invasive alternatives include nasoalveolar moulding.

- Consists of an intraoral plate with attached nasal moulding bulbs.

- Include the Latham appliance.

- Passive appliances

- Not all units utilise presurgical orthodontics; its use is controversial.

- Some reserve it for severe deformities, such as a wide bilateral CL&P.

- There is some evidence that presurgical orthodontics may be detrimental to subsequent growth, although this effect is probably largely related to the Latham.

Lip adhesion

- Essentially converts a difficult wide cleft into a less difficult incomplete cleft.

- Shapes and repositions a protruding premaxillary segment in cases of bilateral CL.

- Can also narrow a wide cleft, facilitating definitive repair.

- May be done at any age, under local or general anaesthesia.

- Skin and mucosal flaps are planned within tissue to be discarded in a definitive lip repair.

- Definitive lip repair is planned 3 months later, after the tissues have softened.

- Disadvantages include possible need for general anaesthesia, additional scar tissue and dehiscence.

- Shapes and repositions a protruding premaxillary segment in cases of bilateral CL.

Techniques of repair

- Principles of management:

- Optimisation of function

- Feeding and growth

- Speech

- Dentition

- Hearing.

- Feeding and growth

- Optimisation of appearance.

- Optimisation of function

- The aims of CL repair are to create:

- A lip that moves normally

- A lip of normal length and width

- Well-aligned anatomical landmarks of the lip:

- Vermilion border, wet–dry mucosal junction (red line), white roll, Cupid’s bow, philtral columns, philtral dimple and nasal sill.

- Symmetry

- Minimal scar.

- A lip that moves normally

- Each technique lengthens the shortened lip on the cleft side, usually by a form of modified Z-plasty.

- The most common techniques are based on either the Millard or Tennison–Randall.

- Whichever technique is used, it is important to perform a functional muscle repair:

- Detach abnormal muscle insertions

- Reconstruct the lip musculature

- The nasalis group of muscles should be attached to the anterior nasal spine

- The orbicularis group of muscles should be attached to each other.

- The nasalis group of muscles should be attached to the anterior nasal spine

- Detach abnormal muscle insertions

Straight-line techniques

- Rose-Thompson

- Mirault-Blair-Brown-McDowell

Upper Z-plasties

- Millard

- Delaire

Lower Z-plasties

- Tennison–Randall

- Le Mesurier (rectangular flaps)

Upper and lower Z-plasties

- Skoog

- Trauner.

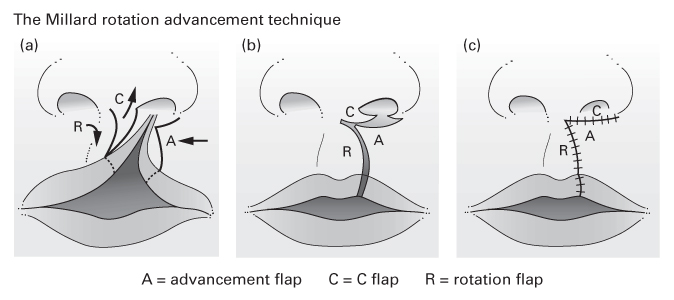

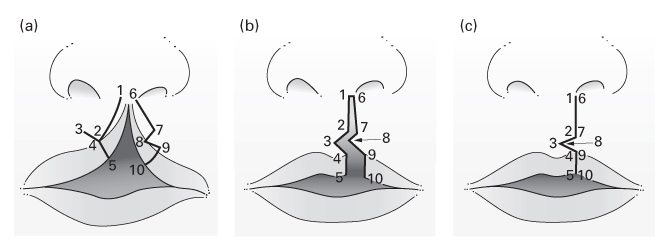

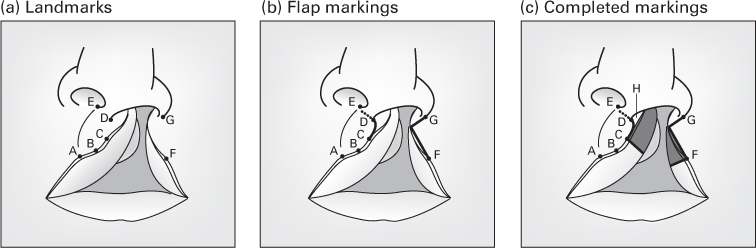

The Millard rotation–advancement technique

- An upper triangular flap is advanced into the rotation defect of the medial segment.

- Advantages:

- The scar ‘recreates’ the philtral column