Chapter 1

General Principles

- Embryology, structure and function of the skin

- Blood supply to the skin

- Classification of flaps

- Geometry of local flaps

- Wound healing and skin grafts

- Bone healing and bone grafts

- Cartilage healing and cartilage grafts

- Nerve healing and nerve grafts

- Tendon healing

- Transplantation

- Tissue engineering

- Alloplastic implantation

- Wound dressings

- Sutures and suturing

- Tissue expansion

- Lasers

- Local anaesthesia

- Microsurgery

- Haemostasis and thrombosis

- Further reading

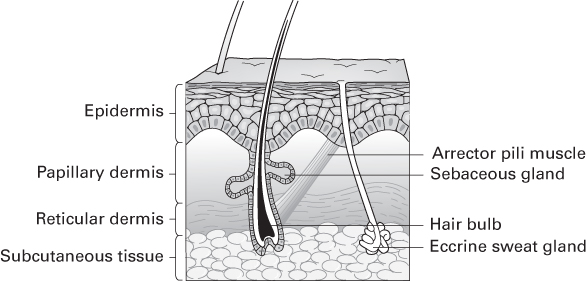

Embryology, structure and function of the skin

- Skin differentiates from ectoderm and mesoderm during the 4th week.

- Skin gives rise to:

- Teeth and hair follicles, derived from epidermis and dermis

- Fingernails and toenails, derived from epidermis only.

- Hair follicles, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, apocrine glands and mammary glands are ‘epidermal appendages’ because they develop as ingrowths of epidermis into dermis.

- Functions of skin:

- Physical protection

- Protection against UV light

- Protection against microbiological invasion

- Prevention of fluid loss

- Regulation of body temperature

- Sensation

- Immunological surveillance.

- Sensation

- Skin gives rise to:

The epidermis

- Composed of stratified squamous epithelium.

- Derived from ectoderm.

- Epidermal cells undergo keratinisation—their cytoplasm is replaced with keratin as the cell dies and becomes more superficial.

- Rete ridges are epidermal thickenings that extend downward between dermal papillae.

- Epidermis is composed of these five layers, from deep to superficial:

- Stratum germinativum

- Also known as the basal layer.

- Cells within this layer have cytoplasmic projections (hemidesmosomes), which firmly link them to the underlying basal lamina.

- The only actively proliferating layer of skin.

- Stratum germinativum also contains melanocytes.

- Also known as the basal layer.

- Stratum spinosum

- Also known as the prickle cell layer.

- Contains large keratinocytes, which synthesise cytokeratin.

- Cytokeratin accumulates in aggregates called tonofibrils.

- Bundles of tonofibrils converge into numerous desmosomes (prickles), forming strong intercellular contacts.

- Also known as the prickle cell layer.

- Stratum granulosum

- Contains mature keratinocytes, with cytoplasmic granules of keratohyalin.

- The predominant site of protein synthesis.

- Combination of cytokeratin tonofibrils with keratohyalin produces keratin.

- Contains mature keratinocytes, with cytoplasmic granules of keratohyalin.

- Stratum lucidum

- A clear layer, only present in the thick glabrous skin of palms and feet.

- Stratum corneum

- Contains non-viable keratinised cells, having lost their nuclei and cytoplasm.

- Protects against trauma.

- Insulates against fluid loss.

- Protects against bacterial invasion and mechanical stress.

- Contains non-viable keratinised cells, having lost their nuclei and cytoplasm.

Cellular composition of the epidermis

- Keratinocytes—the predominant cell type in the epidermis.

- Langerhans cells—antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the immune system.

- Merkel cells—mechanoreceptors of neural crest origin.

- Melanocytes—neural crest derivatives:

- Usually located in the stratum germinativum.

- Produce melanin packaged in melanosomes, which is delivered along dendrites to surrounding keratinocytes.

- Melanosomes form a cap over the nucleus of keratinocytes, protecting DNA from UV light.

- Usually located in the stratum germinativum.

The dermis

- Accounts for 95% of the skin’s thickness.

- Derived from mesoderm.

- Papillary dermis is superficial; contains more cells and finer collagen fibres.

- Reticular dermis is deeper; contains fewer cells and coarser collagen fibres.

- It sustains and supports the epidermis.

- Dermis is composed of:

- Collagen fibres

- Produced by fibroblasts.

- Through cross-linking, are responsible for much of the skin’s strength.

- The normal ratio of type 1 to type 3 collagen is 5:1.

- Produced by fibroblasts.

- Elastin fibres

- Secreted by fibroblasts.

- Responsible for elastic recoil of skin.

- Secreted by fibroblasts.

- Ground substance

- Consists of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs): hyaluronic acid, dermatan sulphate, chondroitin sulphate.

- GAGs are secreted by fibroblasts and become ground substance when hydrated.

- Consists of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs): hyaluronic acid, dermatan sulphate, chondroitin sulphate.

- Vascular plexus

- Separates the denser reticular dermis from the overlying papillary dermis.

Skin appendages

Hair follicles

- Each hair is composed of a medulla, a cortex and an outer cuticle.

- Hair follicles consist of an inner root sheath (derived from epidermis), and an outer root sheath (derived from dermis).

- Several sebaceous glands drain into each follicle.

- Drainage of the glands is aided by contraction of arrector pili muscles.

- Vellus hairs are fine and downy; terminal hairs are coarse.

- Hairs are either in anagen (growth), catagen (regressing), or telogen (resting) phase.

- <90% are in anagen, 1–2% in catagen and 10–14% in telogen at any one time.

Eccrine glands

- These sweat glands secrete odourless hypotonic fluid.

- Present in almost all sites of the body.

- Occur more frequently in the palm, sole and axilla.

Apocrine glands

- Located in axilla and groin.

- Emit a thicker secretion than eccrine glands.

- Responsible for body odour; do not function before puberty.

- Modified apocrine glands are found in the external ear (ceruminous glands) and eyelid (Moll glands).

- The mammary gland is a modified apocrine gland specialised for manufacture of colostrum and milk.

- Hidradenitis suppurativa is a disease of apocrine glands.

Sebaceous glands

- Holocrine glands that drain into the pilosebaceous unit in hair-bearing skin.

- They drain directly onto skin in the labia minora, penis and tarsus (meibomian glands).

- Most prevalent on forehead, nose and cheek; absent from palms and soles.

- Produce sebum, which contains fats and their breakdown products, wax esters and debris of dead fat-producing cells.

- Sebum is bactericidal to staphylococci and streptococci.

- Sebaceous glands are not the sole cause of so-called sebaceous cysts.

- These cysts are in fact of epidermal origin and contain all substances secreted by skin (predominantly keratin).

- Some maintain they should therefore be called epidermoid cysts.

Types of secretion from glands

- Eccrine or merocrine glands secrete opened vesicles via exocytosis.

- Apocrine glands secrete by ‘membrane budding’—pinching off part of the cytoplasm in vesicles bound by the cell’s own plasma membrane.

- Holocrine gland secretions are produced within the cell, followed by rupture of the cell’s plasma membrane.

Histological terms

- Acanthosis: epidermal hyperplasia.

- Papillomatosis: increased depth of corrugations at the dermoepidermal junction.

- Hyperkeratosis: increased thickness of the keratin layer.

- Parakeratosis: presence of nucleated cells at the skin surface.

- Pagetoid: when cells invade the upper epidermis from below.

- Palisading: when cells are oriented perpendicular to a surface.

- Pagetoid: when cells invade the upper epidermis from below.

Blood supply to the skin

- Epidermis contains no blood vessels.

- It is dependent on dermis for nutrients, supplied by diffusion.

Anatomy of the circulation

- Blood reaching the skin originates from named deep vessels.

- These feed interconnecting vessels, which supply the vascular plexuses of fascia, subcutaneous tissue and skin.

Deep vessels

- Arise from the aorta and divide to form the main arterial supply to head, neck, trunk and limbs.

Interconnecting vessels

- The interconnecting system is composed of:

- Fasciocutaneous (or septocutaneous) vessels

- Reach the skin directly by traversing fascial septa.

- Provide the main arterial supply to skin in the limbs.

- Reach the skin directly by traversing fascial septa.

- Fasciocutaneous (or septocutaneous) vessels

- Musculocutaneous vessels

- Reach the skin indirectly via muscular branches from the deep system.

- These branches enter muscle bellies and divide into multiple perforating branches, which travel up to the skin.

- Provide the main arterial supply to skin of the torso.

- Reach the skin indirectly via muscular branches from the deep system.

Vascular plexuses of fascia, subcutaneous tissue and skin

- Subfascial plexus

- Small plexus lying on the undersurface of deep fascia.

- Prefascial plexus

- Larger plexus superficial to deep fascia; prominent on the limbs.

- Predominantly supplied by fasciocutaneous vessels.

- Larger plexus superficial to deep fascia; prominent on the limbs.

- Subcutaneous plexus

- At the level of superficial fascia.

- Mainly supplied by musculocutaneous vessels.

- Predominant on the torso.

- At the level of superficial fascia.

- Subdermal plexus

- Receives blood from the underlying plexuses.

- The main plexus supplying blood to skin.

- Accounts for dermal bleeding observed in incised skin.

- Receives blood from the underlying plexuses.

- Dermal plexus

- Mainly composed of arterioles.

- Plays an important role in thermoregulation.

- Subepidermal plexus

- Contains small vessels without muscle in their walls.

- Predominantly nutritive and thermoregulatory function.

- Mainly composed of arterioles.

Angiosomes

- An angiosome is a three-dimensional composite block of tissue supplied by a named artery.

- The area of skin supplied by an artery was first studied by Manchot in 1889.

- His work was expanded by Salmon in the 1930s, and more recently by Taylor and Palmer.

- The anatomical territory of an artery is the area into which the vessel ramifies before anastomosing with adjacent vessels.

- The dynamic territory of an artery is the area into which staining extends after intravascular infusion of fluorescein.

- The potential territory of an artery is the area that can be included in a flap if it is delayed.

- Vessels that pass between anatomical territories are called choke vessels.

- The transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap illustrates the angiosome concept well:

Zone 1

- Receives musculocutaneous perforators from the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) and is therefore in its anatomical territory.

Zones 2 and 3

- There is controversy as to which of the following zones is 2 and which is 3.

- Hartrampf’s 1982 description has zone 2 across the midline and zone 3 lateral to zone 1.

- Holm’s 2006 study shows the opposite to be true.

- Skin lateral to zone 1 is in the anatomical territory of the superficial circumflex iliac artery (SCIA).

- Blood has to travel through a set of choke vessels to reach it from the ipsilateral DIEA.

- Skin on the contralateral side of the linea alba is in the anatomical area of the ipsilateral DIEA.

- It is also within the dynamic territory of the contralateral DIEA.

- This allows a TRAM flap to be reliably perfused based on either DIEA.

- It is also within the dynamic territory of the contralateral DIEA.

Zone 4

- This lies furthest from the pedicle and is in the anatomical territory of the contralateral SCIA.

- Blood passing from the pedicle to zone 4 has to cross two sets of choke vessels.

- This portion of the TRAM flap has the worst blood supply and is often discarded.

Arterial characteristics

- Taylor made the following observations from his detailed anatomical dissections:

- Vessels usually travel with nerves.

- Vessels obey the law of equilibrium—if one is small, its neighbour will tend to be large.

- Vessels travel from fixed to mobile tissue.

- Vessels have a fixed destination but varied origin.

- Vessel size and orientation is a product of growth.

- Vessels have a fixed destination but varied origin.

- Vessels usually travel with nerves.

Venous characteristics

- Venous networks consist of linked valvular and avalvular channels that allow equilibrium of flow and pressure.

- Directional veins are valved; typically found in subcutaneous tissues of limbs or as a stellate pattern of collecting veins.

- Oscillating avalvular veins allow free flow between valved channels of adjacent venous territories.

- They mirror and accompany choke arteries.

- They define the perimeter of venous territories in the same way choke arteries define arterial territories.

- They mirror and accompany choke arteries.

- Superficial veins follow nerves; perforating veins follow perforating arteries.

The microcirculation

- Terminal arterioles are found in reticular dermis.

- They terminate as they enter the capillary network.

- The precapillary sphincter is the last part of the arterial tree containing muscle within its wall.

- It is under neural control and regulates blood flow into the capillary network.

- The skin’s blood supply far exceeds its nutritive requirements.

- It bypasses capillary beds via arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) and has a primarily thermoregulatory function.

- AVAs connect arterioles to efferent veins.

- AVAs are of two types:

- Indirect AVAs—convoluted structures known as glomera (sing. glomus)

- Densely innervated by autonomic nerves.

- Direct AVAs—less convoluted with sparser autonomic supply.

- Indirect AVAs—convoluted structures known as glomera (sing. glomus)

Control of blood flow

- The muscular tone of vessels is controlled by:

Pressure of the blood within vessels (myogenic theory)

- Originally described by Bayliss, states that:

- Increased intraluminal pressure results in constriction of vessels.

- Decreased intraluminal pressure results in their dilatation.

- Increased intraluminal pressure results in constriction of vessels.

- Helps keep blood flow constant; accounts for hyperaemia on release of a tourniquet.

Neural innervation

- Arterioles, AVAs and precapillary sphincters are sympathetically innervated.

- Increased arteriolar tone results in decreased cutaneous blood flow.

- Increased precapillary sphincter tone reduces blood flow into capillary networks.

- Decreased AVA tone increases non-nutritive blood flow bypassing the capillary bed.

Humoral factors

- Epinephrine, norepinephrine, serotonin, thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin F2α cause vasoconstriction.

- Histamine, bradykinin and prostaglandin E1 cause vasodilatation.

- Low O2 saturation, high CO2 saturation and acidosis also cause vasodilatation.

Temperature

- Heat causes cutaneous vasodilatation and increased flow, which predominantly bypasses capillary beds via AVAs.

The delay phenomenon

- Delay is any preoperative manoeuvre that results in increased flap survival.

- Historical examples include Tagliacozzi’s nasal reconstruction described in the 16th century.

- Involves elevation of a bipedicled flap with length : breadth ratio of 2:1.

- The flap can be considered as two 1:1 flaps.

- Cotton lint is placed under the flap, preventing its reattachment.

- Two weeks later, one end of the flap is detached from the arm and attached to the nose.

- A flap of these dimensions transferred without a delay procedure would have a significant chance of distal necrosis.

- Involves elevation of a bipedicled flap with length : breadth ratio of 2:1.

- Delay is occasionally used for pedicled TRAM breast reconstruction.

- The DIEA is ligated two weeks prior to flap transfer.

- The mechanism of delay remains incompletely understood.

- These theories have been proposed to explain the delay phenomenon:

Increased axiality of blood flow

- Removal of blood flow from the periphery of a random flap promotes development of an axial blood supply from its base.

- Axial flaps have improved survival compared to random flaps.

Tolerance to ischaemia

- Cells become accustomed to hypoxia after the initial delay procedure.

- Less tissue necrosis therefore occurs after the second operation.

Sympathectomy vasodilatation theory

- Dividing sympathetic fibres at the borders of a flap results in vasodilatation and improved blood supply.

- But why, if sympathectomy is immediate, does the delay phenomenon only begin to appear at 48 hours, and why does it take 2 weeks for maximum effect?

Intraflap shunting hypothesis

- Postulates that sympathectomy dilates AVAs, resulting in an increase in nonnutritive blood flow bypassing the capillary bed.

- A greater length of flap will survive at the second stage as there are fewer sympathetic fibres to cut and therefore less of a reduction in nutritive blood flow.

Hyperadrenergic state

- Surgery results in increased tissue concentrations of vasoconstrictors, such as epinephrine and norepinephrine.

- After the initial delay procedure, the resultant reduction in blood supply is not sufficient to produce tissue necrosis.

- The level of vasoconstrictor substances returns to normal before the second procedure.

- The second procedure produces another rise in the concentration of vasoconstrictor substances.

- This rise is said to be smaller than it would be if the flap were elevated without a prior delay.

- The flap is therefore less likely to undergo distal necrosis after a delay procedure.

- After the initial delay procedure, the resultant reduction in blood supply is not sufficient to produce tissue necrosis.

Unifying theory

- Described by Pearl in 1981; incorporates elements of all these theories.

Classification of flaps

- Flaps can be classified by the five ‘C’s:

- Circulation

- Composition

- Contiguity

- Contour

- Conditioning.

- Circulation

Circulation

- Can be further subcategorised into:

- Random

- Axial (direct, fasciocutaneous, musculocutaneous, or venous).

- Random

Random flaps

- No directional blood supply; not based on a named vessel.

- These include most local flaps on the face.

- Should have a maximum length : breadth ratio of 1:1 in the lower extremity, as it has a relatively poor blood supply.

- Can be up to 6:1 in the face, as it has a good blood supply.

Axial flaps

Direct

- Contain a named artery running in subcutaneous tissue along the axis of the flap.

- Examples include:

- Groin flap, based on superficial circumflex iliac vessels.

- Deltopectoral flap, based on perforating vessels of internal mammary artery.

- Groin flap, based on superficial circumflex iliac vessels.

- Both flaps can include a random segment in their distal portions after the artery peters out.

Fasciocutaneous

- Based on vessels running either within or near the fascia.

- The fasciocutaneous system predominates on the limbs.

- Fasciocutaneous flaps are classified by Cormack and Lamberty:

- The fasciocutaneous system predominates on the limbs.

Type A

- Dependent on multiple non-named fasciocutaneous vessels that enter the base of the flap.

- Lower leg ‘super flaps’ described by Pontén are examples of type A flaps.

- Their dimensions vastly exceed the 1:1 ratios recommended.

Type B

- Based on a single fasciocutaneous vessel, which runs along the axis of the flap.

- Examples include scapular/parascapular flap, and perforator-based fasciocutaneous flaps of the lower leg.

Type C

- Supplied by multiple small perforating vessels, which reach the flap from a deep artery running along a fascial septum between muscles.

- Examples include radial forearm flap (RFF) and lateral arm flap.

Type C flaps with bone

- Osteofasciocutaneous flaps, originally classified as type D.

- Examples include:

- RFF raised with a segment of radius; lateral arm flap raised with a segment of humerus.

- The Mathes and Nahai fasciocutaneous flap classification is slightly different:

Type A

- Direct cutaneous pedicle.

- Examples: groin, superficial inferior epigastric and dorsal metacarpal artery flaps.

Type B

- Septocutaneous pedicle.

- Examples: scapular and parascapular, lateral arm, posterior interosseous flap.

Type C

- Musculocutaneous pedicle.

- Examples: median forehead, nasolabial and (usually) anterolateral thigh flap.

Musculocutaneous

- Flaps based on perforators that reach the skin through the muscle.

- The musculocutaneous system predominates on the torso.

- Muscle and musculocutaneous flaps were classified by Mathes and Nahai in 1981:

Type I

- Single vascular pedicle.

- Examples: gastrocnemius, tensor fasciae latae (TFL), abductor digiti minimi.

- Good flaps for transfer—the whole muscle is supplied by a single pedicle.

- Examples: gastrocnemius, tensor fasciae latae (TFL), abductor digiti minimi.

Type II

- Dominant pedicle(s) and other minor pedicle(s).

- Examples: trapezius, soleus, gracilis.

- Good flaps for transfer—can be based on the dominant pedicle after the minor pedicle(s) are ligated.

- Circulation via minor pedicles alone is not reliable.

Type III

- Two dominant pedicles, each arising from a separate regional artery or opposite sides of the muscle.

- Examples: rectus abdominis, pectoralis minor, gluteus maximus.

- Useful muscles for transfer—can be based on either pedicle.

Type IV

- Multiple segmental pedicles.

- Examples: sartorius, tibialis anterior, long flexors and extensors of the toes.

- Seldom used for transfer—each pedicle supplies only a small portion of muscle.

Type V

- One dominant pedicle and secondary segmental pedicles.

- Examples: latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major.

- Useful flaps—can be based on either the dominant pedicle or secondary segmental pedicles.

Venous

- Based on venous, rather than arterial, pedicles.

- In fact, many venous pedicles have small arteries running alongside them.

- The mechanism of perfusion is not completely understood.

- Example: saphenous flap, based on long saphenous vein.

- Used to reconstruct defects around the knee.

- Venous flaps are classified by Thatte and Thatte:

Type 1

- Single venous pedicle.

Type 2

- Venous flow-through flaps, supplied by a vein that enters one side of the flap and exits from the other.

Type 3

- Arterialised through a proximal arteriovenous anastomosis and drained by distal veins.

- Venous flaps tend to become congested post-operatively.

- Survival is inconsistent; they have therefore not been universally accepted.

- Modifying the type 3 arterialised venous flap by restricting direct arteriovenous shunting can improve survival rates by redistributing blood to the periphery of the flap.

- Venous flaps tend to become congested post-operatively.

Composition

- Flaps can be classified by their composition as:

- Cutaneous

- Fasciocutaneous

- Fascial

- Musculocutaneous

- Muscle only

- Osseocutaneous

- Osseous.

- Cutaneous

Contiguity

- Flaps can be classified as:

- Local flaps

- Composed of tissue adjacent to the defect.

- Regional flaps

- Composed of tissue from the same region of the body as the defect, e.g. head and neck, upper limb.

- Distant flaps

- Pedicled distant flaps come from a distant part of the body to which they remain attached.

- Free flaps are completely detached from the body and anastomosed to recipient vessels close to the defect.

- Pedicled distant flaps come from a distant part of the body to which they remain attached.

- Local flaps

Contour

- Flaps can be classified by the way they are transferred into the defect:

Advancement

- Stretching the flap

- Excision of Burow triangles at the flap’s base

- V-Y advancement

- Z-plasty at its base

- Careful scoring of the undersurface

- Combinations of the above.

Transposition

- The flap is moved into an adjacent defect, leaving a secondary defect that must be closed by another method.

Rotation

- The flap is rotated into the defect.

- Classically, rotation flaps are designed to allow closure of the donor defect.

- In reality, many flaps have elements of transposition and rotation, and may be best described as pivot flaps.

- Classically, rotation flaps are designed to allow closure of the donor defect.

Interpolation

- The flap is moved into a defect either under or above an intervening bridge of tissue.

Crane principle

- This aims to transform an ungraftable bed into one that will accept a skin graft.

- At the first stage, a flap is placed into the defect.

- After sufficient time to allow vascular ingrowth into the flap from the recipient site, a superficial part of the flap is replaced in its original position.

- This leaves a segment of subcutaneous tissue in the defect, which can now accept a skin graft.

Conditioning

- This involves delaying the flap, discussed in ‘Blood supply to the skin’.

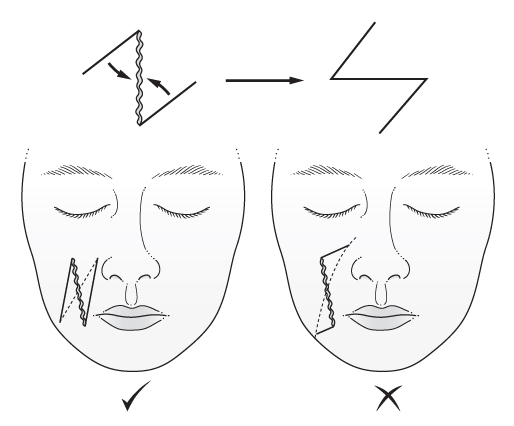

Geometry of local flaps

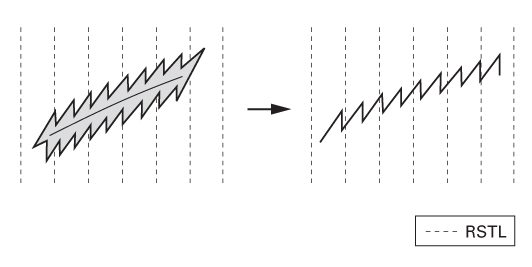

Orientation of elective incisions

- In the 19th century, Langer showed that circular awl wounds produced elliptical defects in cadaver skin.

- He believed this occurred because skin tension along the longitudinal axis of the ellipse exceeded that along the transverse axis.

- Borges has provided over 36 descriptive terms for skin lines, including:

- Relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs)—these are parallel to natural skin wrinkles (rhytids) and tend to be perpendicular to the fibres of underlying muscles.

- Lines of maximum extensibility (LME)—these lie perpendicular to RSTLs and parallel to the fibres of underlying muscles.

- Relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs)—these are parallel to natural skin wrinkles (rhytids) and tend to be perpendicular to the fibres of underlying muscles.

- The best orientation of an incision can be judged by a number of methods:

- Knowledge of the direction of pull of underlying muscles.

- Making the incision parallel to any rhytids or RSTLs.

- Making the incision perpendicular to LMEs.

- Making the incision parallel to the direction of hair growth.

- ‘The pinch test’—if skin either side of the planned incision is pinched, it forms a transverse fold without distortion if it is orientated correctly; if a sigmoid-shaped fold forms, it is orientated incorrectly.

- Knowledge of the direction of pull of underlying muscles.

Plasty techniques

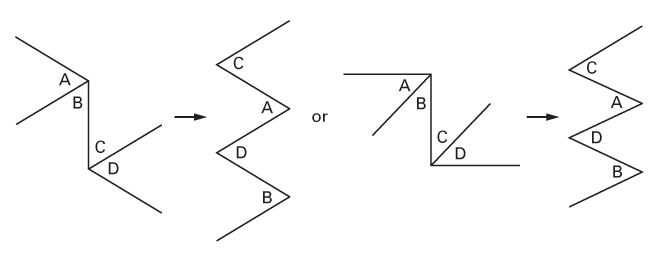

Z-plasty

- Involves transposition of two adjacent triangular-shaped flaps.

- Can be used to:

- Increase the length of an area of tissue or scar

- Break up a straight-line scar

- Realign a scar.

- The degree of elongation of the longitudinal axis of the Z-plasty is directly related to the angles of its constituent flaps.

- 30° → 25% elongation

- 45° → 50% elongation

- 60° → 75% elongation

- 75° → 100% elongation

- 90° → 125% elongation.

- The amount of elongation can be worked out by starting at 30° and 25% and adding 15° and 25% to each of the figures.

- Gains in length are estimates; true values depend on local tissue elasticity and tension.

- Flaps with 60° angles are most commonly used as they lengthen without undue tension.

- The angles of the two flaps need not be equal and can be designed to suit local tissue requirements.

- However, all three limbs should be of the same length.

- When designing a Z-plasty to realign a scar:

- Mark the desired direction of the new scar.

- Draw the central limb of the Z-plasty along the original scar.

- Draw the lateral limbs of the Z-plasty from the ends of the central limb, to the line drawn in (1).

- Two patterns will be available, one with a wide angle at the apex of the flaps, the other with a narrow angle.

- Select the pattern with the narrower angle as these flaps transpose better.

- Increase the length of an area of tissue or scar

The four-flap plasty

- It is, in effect, two interdependent Z-plasties.

- Can be designed with different angles.

- The two outer flaps become the inner flaps after transposition.

- The two inner flaps become the outer flaps after transposition.

- The flaps, originally in an ‘ABCD’ configuration, end as ‘CADB’ (CADBury).

- Can be designed with different angles.

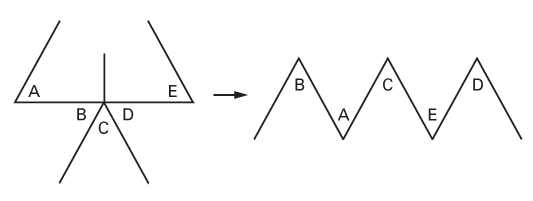

The five-flap plasty

- Because of its appearance, this is also called a jumping-man flap.

- Used to release first web space contractures and epicanthal folds.

- It is, in effect, two opposing Z-plasties with a V-Y advancement in the center.

- The flaps, originally in an ‘ABCDE’ configuration, end as ‘BACED’.

The W-plasty

- Used to break up the line of a scar and improve its aesthetics.

- Unlike the Z-plasty, it does not lengthen tissue.

- If possible, one of the limbs of the W-plasty should lie parallel to the RSTLs so that half of the resultant scar will lie parallel to them.

- Using a template helps ensure each wound edge interdigitates easily.

- The technique discards normal tissue, which may be a disadvantage in certain areas.

Local flaps

- Advancement flaps (simple, modified, V-Y, keystone, bipedicled).

- Pivot flaps (transposition, interpolation, rotation, bilobed).

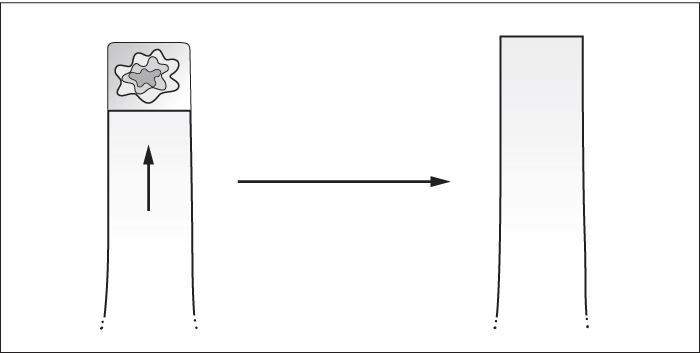

Advancement flaps

Simple

- Rely on skin elasticity.

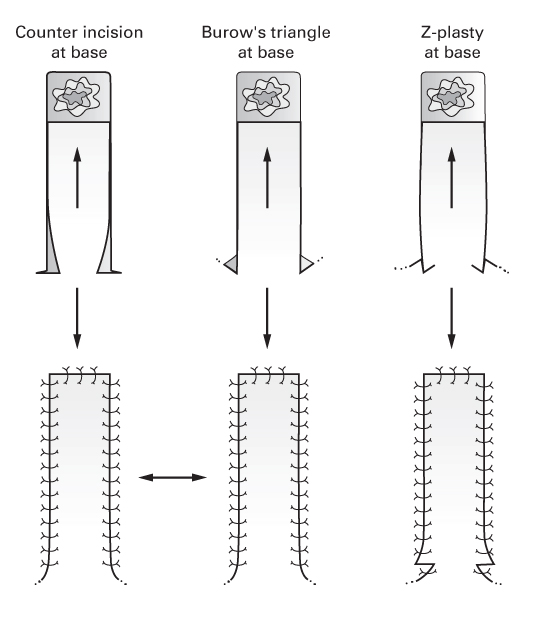

Modified

- Incorporate one of the following at the flap’s base to increase advancement:

- Counter incision

- Excision of Burow’s triangle

- Z-plasty.

- Counter incision

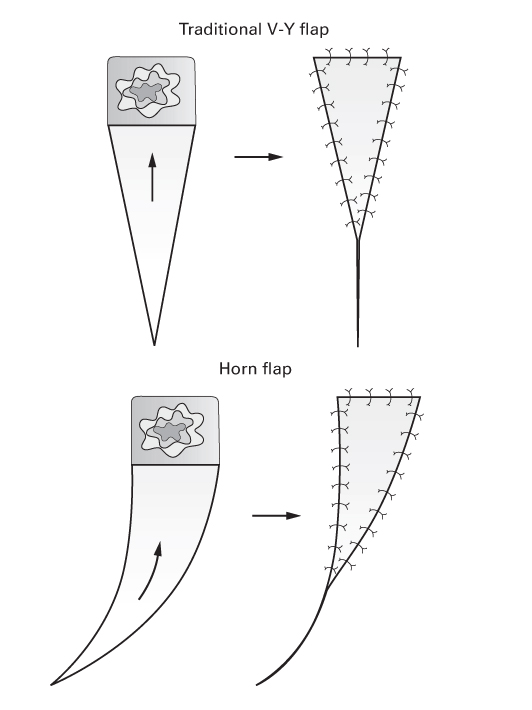

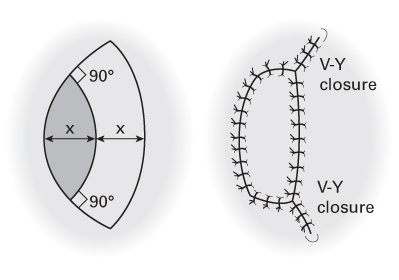

V-Y

- These are incised along their cutaneous borders.

- Their blood supply comes from deep tissue through a subcutaneous pedicle.

- Horn flaps and oblique V-Y flaps are modifications of the original V-Y.

Keystone

- Trapezoidal flaps used to close elliptical defects.

- Essentially two V-Y flaps end-to-side.

- Designed to straddle longitudinal structures, e.g. superficial nerves and veins, which are incorporated into the flap.

- Blunt dissection to deep fascia preserves perforators and subcutaneous veins.

- The lateral deep fascial margin can be incised for increased mobilisation.

- The extremes of the donor site are closed as V-Y advancements, which produces transverse laxity in the flap.

- Essentially two V-Y flaps end-to-side.

Bipedicled

- Receive blood supply from both ends.

- Less prone to necrosis than flaps of similar dimensions attached only at one end.

- Example: von Langenbeck mucoperiosteal flap, used to repair cleft palates.

- Bipedicled flaps are designed to curve parallel with the defect.

- This permits flap transposition with less tension.

- Less prone to necrosis than flaps of similar dimensions attached only at one end.

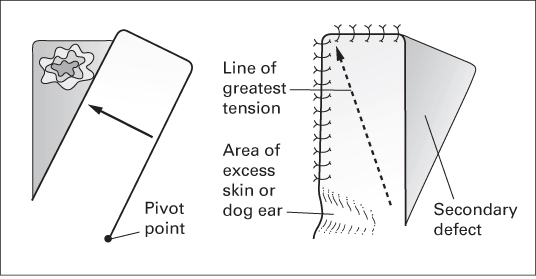

Pivot flaps

Transposition flaps

- Transposed into the defect, leaving a donor site that is closed by some other means (often a skin graft).

Transposition flaps with direct closure of donor site

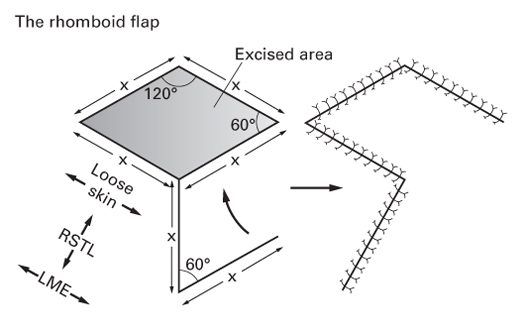

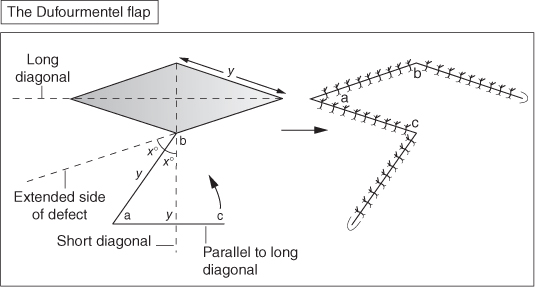

- Include the rhomboid flap (Limberg flap) and Dufourmentel flap.

- These are similar in concept but vary in geometry.

- Both are designed to leave the donor site scar parallel to RSTLs.

The rhomboid flap

The Dufourmentel flap

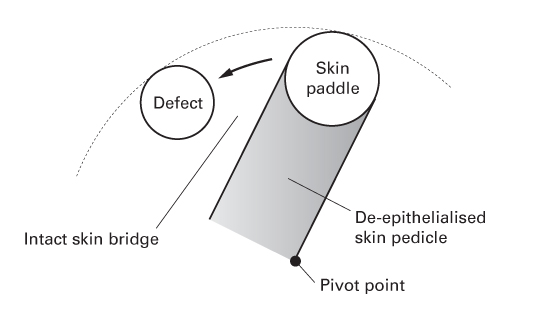

Interpolation flaps

- Flaps raised from local, but not adjacent, skin.

- The pedicle is passed either over or under an intervening skin bridge.

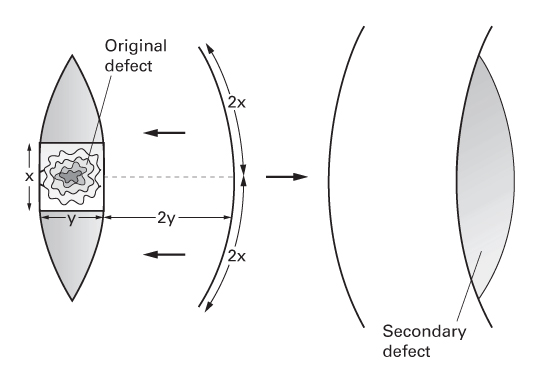

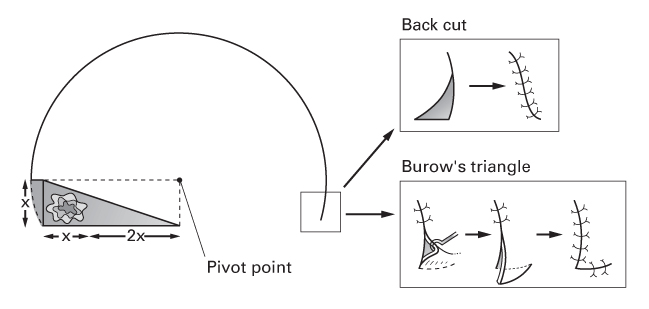

Rotation flaps

- These large flaps rotate tissue into the defect.

- Tissue redistribution usually permits direct closure of the donor site.

- Flap circumference should be 5–8 times the width of the defect.

- These are used on the scalp for hair-bearing reconstruction.

- The back cut at the flap’s base can be directed towards or away from the defect.

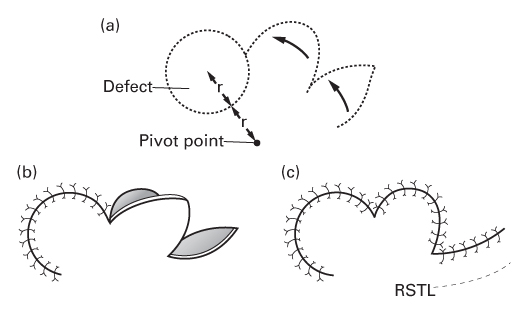

The bilobed flap

- Various designs have been described.

- Consists of two transposition flaps.

- The first flap is transposed into the original defect.

- The second flap is transposed into the secondary defect—the donor site of the first flap.

- The tertiary defect at the donor site of the second flap closes directly.

- This suture line is designed to lie parallel to RSTLs.

- Esser, who first described the flap, put the first flap at 90° to the defect and the second flap at 90° to the first flap.

- Zitelli modified these angles to 45° each, resulting in smaller dog ears.

- Consists of two transposition flaps.

Wound healing and skin grafts

- Healing by primary intention

- Skin edges are directly opposed.

- Healing is normally good, with minimal scar formation.

- Skin edges are directly opposed.

- Healing by secondary intention

- The wound is left open to heal by a combination of granulation tissue formation, contraction and epithelialisation.

- More inflammation and proliferation occurs compared to primary healing.

- Healing by tertiary intention

- Wounds are initially left open, then closed as a secondary procedure.

- The wound is left open to heal by a combination of granulation tissue formation, contraction and epithelialisation.

Phases of wound healing

- Haemostasis

- Inflammation

- Proliferation

- Remodelling.

Haemostasis

- Vasoconstriction occurs immediately after vessel division due to release of thromboxanes and prostaglandins from damaged cells.

- Platelets bind to exposed collagen, forming a platelet plug.

- Platelet degranulation activates more platelets and increases their affinity to bind fibrinogen.

- Involves modification of membrane glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (blocked by clopidogrel).

- Platelet activating factor (PAF), von Willebrand factor (vWF) and thromboxane A2 stimulate conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.

- This propagates formation of thrombus.

- Thrombus is initially pale when it contains platelets alone (white thrombus).

- As red blood cells are trapped, the thrombus becomes darker (red thrombus).

Inflammation

- Occurs in the first 2–3 days after injury.

- Stimulated by physical injury, antigen–antibody reaction or infection.

- Platelets release growth factors, e.g. platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).

- Also release proinflammatory factors, e.g. serotonin, bradykinin, prostaglandins, thromboxanes and histamine.

- These increase cell proliferation and migration.

- Also release proinflammatory factors, e.g. serotonin, bradykinin, prostaglandins, thromboxanes and histamine.

- Endothelial cells swell, causing vasodilatation and allowing egress of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and monocytes into the tissue.

- T lymphocytes migrate into the wound under the influence of interleukin-1.

- Lymphocytes secrete various cytokines, including epidermal growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF).

- They also play a role in cellular immunity and antibody production.

Proliferation

- Begins on the 2nd or 3rd day and lasts for 2–4 weeks.

- Monocytes mature into macrophages that release PDGF and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which are chemoattractant to fibroblasts.

- Fibroblasts, usually located in perivascular tissue, migrate along fibrin networks into the wound.

- Fibroblasts secrete GAGs to produce ground substance, and then produce collagen and elastin.

- Initially, type III collagen is produced to increase the strength of the wound.

- Some fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts and effect wound contraction.

- Angiogenesis occurs concurrently to supply oxygen and nutrients to the wound.

- Endothelial stem cells from blood vessels migrate through extracellular matrix.

- Attracted to the wound by angiogenic factors, thrombus and local hypoxia.

- Zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinases aid cell migration through tissues.

Remodelling

- Begins 2–4 weeks after injury and can last a year or longer.

- During remodelling there is no net increase in collagen (collagen homeostasis).

- Type III collagen is replaced by the stronger type I collagen.

- Collagen fibres, initially laid down haphazardly, are arranged in a more organised manner.

- The wound’s tensile strength approaches 50% of normal by 3 months; eventually becomes 80% as strong.

- The extensive capillary network is no longer required and is removed by apoptosis, leaving a pale collagen scar.

Abnormal scars

- Classified as either hypertrophic or keloid.

- Keloids extend beyond the original wound margins.

- Hypertrophic scars are limited to original wound margins; commoner than keloids.

- Keloids extend beyond the original wound margins.

- Increased numbers of mast cells in abnormal scars may account for the pruritus experienced by some patients.

Hypertrophic scars

- Usually occurs within 8 weeks of wounding.

- Grow rapidly for up to 6 months before gradually regressing to a flat, asymptomatic scar.

- This may take a few years.

- Typically form at locations under tension, e.g. shoulders, neck, presternal area, knees, ankles.

- Microscopy shows well-organised type III collagen bundles with nodules containing myofibroblasts.

Keloid scars

- Dark-skinned individuals are more prone to keloid scars.

- There is often a family history.

- May develop at any point up to several years after minor injuries.

- Typically persist for long periods of time and do not regress spontaneously.

- Pain and hypersensitivity are associated more with keloids than hypertrophic scars.

- Commonly form on anterior chest, shoulders, earlobes, upper arms and cheeks.

- Excision typically results in recurrence.

- Microscopy shows poorly organised type I and III collagen bundles with few myofibroblasts.

- Expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and p53 is upregulated.

Epithelial repair

- If the epidermal basement membrane is not breached, epithelial cells are replaced by upward migration of keratinocytes as in uninjured skin.

- If the basement membrane is breached, re-epithelialisation must occur from the wound margins and, if present and intact, from epidermal appendages.

- Re-establishing epithelial continuity consists of these four phases:

Mobilisation

- Epithelial cells at the wound edges elongate, flatten and form pseudopodia.

- They detach from neighbouring cells and basement membrane.

Migration

- Decreased contact inhibition promotes cell migration.

- Epithelial cells climb over one another to migrate.

- As cells migrate, epithelial cells at the wound edge proliferate to replace them.

- Cells migrate until they meet those from the opposite wound edge.

- At this point, contact inhibition is reinstituted and migration ceases.

Mitosis

- Epithelial cells proliferate once they have covered the wound.

- They secrete proteins to form a new basement membrane.

- Cells reverse the morphological changes required for migration.

- Desmosomes and hemidesmosomes are re-established to anchor themselves to the basement membrane and to each other.

- This new epithelial cell layer forms a stratum germinativum and undergoes mitosis as in normal skin.

Cellular differentiation

- The normal structure of stratified squamous epithelium is re-established.

Collagen

- Constitutes approximately 30% of total body protein.

- Formed by hydroxylation of amino acids lysine and proline by enzymes that require vitamin C as a cofactor.

- Procollagen is initially formed within the cell.

- Procollagen is transformed into tropocollagen after it is excreted from the cell.

- Fully formed collagen has a complex structure.

- Consists of three polypeptide chains wound in a left-handed helix.

- These three chains are further wound in a right-handed coil to form the basic tropocollagen unit.

- Consists of three polypeptide chains wound in a left-handed helix.

- Collagen formation is inhibited by colchicine, penicillamine, steroids and deficiencies of vitamin C and iron.

- Cortisol stimulates degradation of skin collagen.

- Thus far, 28 types of collagen have been identified.

- Each type shares the same basic structure but differs in the relative composition of hydroxylysine and hydroxyproline, and in the degree of cross-linking between chains.

- The five most common types are:

- Type I: predominant in mature skin, bone and tendon.

- Type II: present in hyaline cartilage and cornea.

- Type III: present in healing tissue, particularly fetal wounds.

- Type IV: predominant constituent of basement membranes.

- Type V: similar to type IV. Also found in hair and placenta.

- The ratio of type I collagen to type III collagen in normal skin is 5:1.

- Hypertrophic and immature scars contain ratios of 2:1 or less.

- 90% of total body collagen is type I.

- Cortisol stimulates degradation of skin collagen.

The macrophage

- Derived from mononuclear leukocytes.

- Debrides tissue and removes micro-organisms.

- Co-ordinates angiogenesis and fibroblast activity by releasing growth factors:

- PDGF, FGF 1 and 2, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and TGF-β.

- Essential for normal wound healing.

- Wounds depleted of macrophages heal slowly.

The myofibroblast

- First identified by Gabbiani in 1971.

- Differs from a fibroblast—contains cytoplasmic filaments of α-smooth muscle actin, which are also found in smooth muscle.

- Actin fibres within myofibroblasts are thought to be responsible for wound contraction.

- The number of myofibroblasts within a wound is proportional to its contraction.

- Increased numbers have been found in the fascia of Dupuytren’s disease.

- Thought to be responsible for the abnormal contraction of this tissue.

TGF-β

- Macrophages, fibroblasts, platelets, keratinocytes and endothelial cells secrete this growth factor.

- Believed to play a central role in wound healing:

- Chemoattraction of fibroblasts and macrophages

- Induction of angiogenesis

- Stimulation of extracellular matrix deposition

- Keratinocyte proliferation.

- Chemoattraction of fibroblasts and macrophages

- Three isoforms have been identified:

- Types 1 and 2 promote wound healing and scarring; upregulated in keloids.

- Type 3 decreases wound healing and scarring—may have a role as an antiscarring agent.

- Types 1 and 2 promote wound healing and scarring; upregulated in keloids.

- Fetal wounds have higher levels of TGF-β3 than adult wounds.

- TGF-β3 is thought to antagonise TGF-β1 and 2.

- May be one factor responsible for decreased inflammation and improved scarring observed in fetal tissue.

- TGF-β3 is thought to antagonise TGF-β1 and 2.

Factors affecting healing

- Systemic

- Congenital

- Acquired

- Congenital

- Local.

Systemic factors: congenital

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Autosomal recessive.

- Characterised by increased collagen degradation and mineralisation.

- Skin is pebbled and extremely lax.

- Most have premature arteriosclerosis in their 30s.

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Heterogeneous collection of connective tissue disorders.

- Most are autosomal dominant.

- Results from defects in synthesis, structure or cross-linking of collagen.

- Clinical features:

- Hypermobile fingers

- Hyperextensible skin

- Fragile connective tissues.

- Hypermobile fingers

- Surgery is avoided if possible—wound healing is poor.

Cutis laxa

- Presents in the neonatal period.

- Skin is abnormally lax.

- Patients have inelastic, coarsely textured, drooping skin.

Progeria

- Characterised by premature ageing.

- Clinical features:

- Growth retardation

- Wrinkled skin

- Baldness

- Atherosclerosis.

- Growth retardation

Werner syndrome

- Autosomal recessive.

- Skin changes similar to scleroderma.

- Elective surgery avoided whenever possible—healing is poor.

Epidermolysis bullosa

- Heterogeneous collection of separate conditions.

- Skin is very susceptible to mechanical stress.

- Blistering may occur after minor trauma (Nikolsky sign).

- The most severe subtype, dermolytic bullous dermatosis (DBD), results in hand fibrosis and syndactyly—the ‘mitten hand’ deformity.

- Patients may develop squamous cell carcinoma in areas of chronic erosion.

- Skin is very susceptible to mechanical stress.

Systemic factors: acquired

Nutrition

- Vitamin A involved in collagen cross-linking; deficiency delays wound healing.

- Vitamin C required for collagen synthesis.

- Vitamin E acts as a membrane stabiliser; deficiency may inhibit healing.

- Zinc, copper and selenium are important cofactors for many enzymes; administration accelerates healing in deficient states.

- Hypoalbuminaemia is associated with poor healing.

Pharmacological

- Steroids decrease inflammation and subsequent wound healing.

- Cytotoxics damage basal keratinocytes.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) decrease collagen synthesis.

- Anti-TNF-α drugs used in rheumatoid may increase post-operative wound complications.

Endocrine abnormalities

- Diabetics often have delayed wound healing; this is multifactorial.

- Untreated hypothyroidism is associated with slow healing.

Age

- Cell multiplication rates decrease with age.

- All stages of healing are therefore protracted.

- Healed wounds have decreased tensile strength in the elderly.

Smoking

- Nicotine is a sympathomimetic that causes vasoconstriction and consequently decreases tissue perfusion.

- Carbon monoxide in cigarette smoke decreases oxygen-carrying capacity of haemoglobin.

- Hydrogen cyanide in cigarette smoke poisons intracellular oxidative metabolism pathways.

Local factors

Infection

- Subclinical wound infection can impair wound healing.

- Wounds with >105 organisms per gram of tissue are considered infected and are unlikely to heal without further treatment.

Radiation

- Causes endothelial cell, capillary and arteriole damage.

- Irradiated fibroblasts secrete less collagen and extracellular matrix.

- Lymphatics are also damaged, resulting in oedema and an increased infection risk.

- Irradiated fibroblasts secrete less collagen and extracellular matrix.

Blood supply

- Decreased tissue perfusion results in decreased wound oxygenation.

- Fibroblasts are oxygen-sensitive and their function is reduced in hypoxic tissue.

- Reduced oxygen delivery results from decreases in:

- Inspired oxygen concentration

- Oxygen transfer to haemoglobin

- Haemoglobin concentration

- Tissue perfusion.

- Inspired oxygen concentration

- Decreased oxygen delivery to tissue reduces:

- Collagen formation

- Extracellular matrix deposition

- Angiogenesis

- Epithelialisation.

- Collagen formation

- Hyperbaric oxygen increases inspired oxygen concentration but its effectiveness relies on good tissue perfusion.

Trauma

- The delicate neoepidermis of healing wounds is disrupted by trauma.

Neural supply

- There is evidence that wounds in denervated tissue heal slowly.

- May contribute to delayed healing observed in some pressure sores, and in patients with diabetes and leprosy.

- Mechanisms are poorly understood, but may be related to levels of chemoattractant neuropeptides in the wound.

Fetal wound healing

- Tissue healing in the first 6 months of fetal life occurs by regeneration rather than scarring.

- Regenerative healing is characterised by absence of scarring.

- Normal dermal structures such as hair follicles form normally.

- Regenerative healing differs from adult healing:

- Reduced inflammation.

- Reduced platelet aggregation and degranulation.

- Reduced angiogenesis.

- Epithelialisation is more rapid.

- Virtually no myofibroblasts and no wound contraction.

- Collagen deposition is rapid, organised and not excessive.

- More type III than type I collagen is laid down.

- The wound contains more water and hyaluronic acid.

- Reduced inflammation.

- Relative proportions of TGF-β isoforms may be responsible for some of these differences.

Skin grafts

- Skin grafts are either full or split thickness.

- Split-skin grafts contain the epidermis and a variable amount of dermis.

- Usually harvested from thigh or buttock.

- Full-thickness skin grafts contain the entire epidermis and dermis.

- Usually harvested from areas that allow direct closure of the donor defect.

- Primary contraction is the immediate recoil observed in freshly harvested skin.

- Due to elastin in the dermis.

- Secondary contracture occurs after the graft has healed.

- Due to myofibroblast activity.

- The thicker the graft, the greater the degree of primary contraction.

- The thinner the graft, the greater the degree of secondary contracture.

- Split-skin grafts contain the epidermis and a variable amount of dermis.

Mechanisms

- Skin grafts heal in four phases:

Adherence

- Fibrin bonds form immediately on applying skin graft to a suitable bed.

Serum imbibition

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree