8

The genetics of breast cancer, risk-reducing surgery and prevention

Genetic predisposition

The presence of a significant family history is the strongest risk factor for the development of breast cancer. Even at extremes of age, the presence of a BRCA1 mutation confers significant risks. A 25-year-old woman who carries a mutation in BRCA1 has a greater risk of developing breast cancer in the following decade than a woman aged 70 years in the general population. About 4–5% of breast cancer is thought to be due to inheritance of a high-penetrance, autosomal-dominant, cancer-predisposing gene.1,2

Multiple primary cancers in one individual or related early-onset cancers in a family pedigree are highly suggestive of a predisposing gene. It is thought that over 25% of breast cancers in women under 30 years of age are due to mutation in a dominant gene, compared with less than 1% in women who develop the disease over 70 years.2 It has recently been found that at least 27% of breast cancers under 30 years of age are due to mutations in the known high-risk genes BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53. Nonetheless, risk is still largely based on family history and the detection rate for mutations in isolated breast cancer cases even at very young ages is considerably less than 10%,6 although sporadic grade 3 triple-negative cancers have a little over a 10% chance of a BRCA1 mutation in women under 40 years of age.7

There are few families where it is possible to be certain of a dominantly inherited susceptibility. However, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (BCLC) data suggest that in families with four or more cases of early-onset or bilateral breast cancer, the risk of an unaffected woman inheriting a mutation in a predisposing gene is close to 50%. These studies have estimated that the majority of such families harbour mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, especially when male breast cancer or ovarian cancer is present. In breast-only families, the frequency of BRCA1/2 involvement falls to below 50% in four-case families.8 Family and epidemiological studies have demonstrated that approximately 70–85% of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers develop breast cancer in their lifetime, although the risk is a little lower for BRCA2.8–11 The very low figures published on small numbers of families from population studies have now been addressed by a meta-analysis,11 which gives risks to 70 years of age of around 70% for BRCA1 and 55% for BRCA2.

The chances that a family with a history of breast and/or ovarian cancer harbours mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 can be assessed from computer models.12–14 We have recently validated these models using a dataset of 258 patients and their samples tested for BRCA1/2 mutations. We found that at the lower levels of likelihood for mutations, the computer models substantially overpredict the presence of mutations, particularly for BRCA1.15 The Manchester manual model was much better at predicting a mutation in both genes and indeed was better than other manual models (Table 8.2). Further indicators for the presence of a BRCA1 mutation within a family are grade and oestrogen receptor status. BRCA1 tumours are more frequently grade 3 and oestrogen receptor negative or triple negative, and often have a medullary-like histology.16 Further studies incorporating pathology information into risk models such as the BOADICEA have improved their prediction accuracy.17 Ovarian cancers that develop in BRCA1/2 families are nearly always non-mucinous epithelial cancers.18

Table 8.2

Scoring system for identification of a pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutation

| BRCA1 | BRCA2 | |

| Female breast cancer < 30 years | 6 | 5 |

| Female breast cancer 30–39 years | 4 | 4 |

| Female breast cancer 40–49 years | 3 | 3 |

| Female breast cancer 50–59 years | 2 | 2 |

| Female breast cancer > 59 years | 1 | 1 |

| Male breast cancer < 60 years | 5 (if BRCA2 tested) | 8 |

| Male breast cancer > 59 years | 5 (if BRCA2 tested) | 5 |

| Ovarian cancer < 60 years | 8 | 5 (if BRCA1 tested) |

| Ovarian cancer > 59 years | 5 | 5 (if BRCA1 tested) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0 | 1 |

| Prostate cancer < 60 years | 0 | 2 |

| Prostate cancer > 59 years | 0 | 1 |

The likelihood of identifying a BRCA1/2 mutation should not be confused with the ability to detect a mutation if one is present in the family. No single technique is able to detect all mutations. Even by sequencing the entire gene (exons and intron/exon boundaries), the detection rate only equates to about 75%. If a strategy is added to detect large deletions or duplications in BRCA1, this can boost detection to around 95%.19

Populations that are more outbred, such as the UK, have larger numbers of mutations and founder mutations occur at lower frequencies. In the past, some laboratories concentrated on the large exons (exon 11 in both genes and exon 10 in BRCA2) and the smaller exons commonly reported to be involved, such as exons 2 and 20 in BRCA1. This cuts down the number of polymerase chain reactions using the protein truncation test (PTT) to as little as five for BRCA1 and four for BRCA2. However, this strategy reduces the sensitivity of identifying mutations down to as little as 50%.19 With the great strides made in reducing cost and time of mutation searching using next generation sequencing these older strategies are now outdated.

Genetic testing

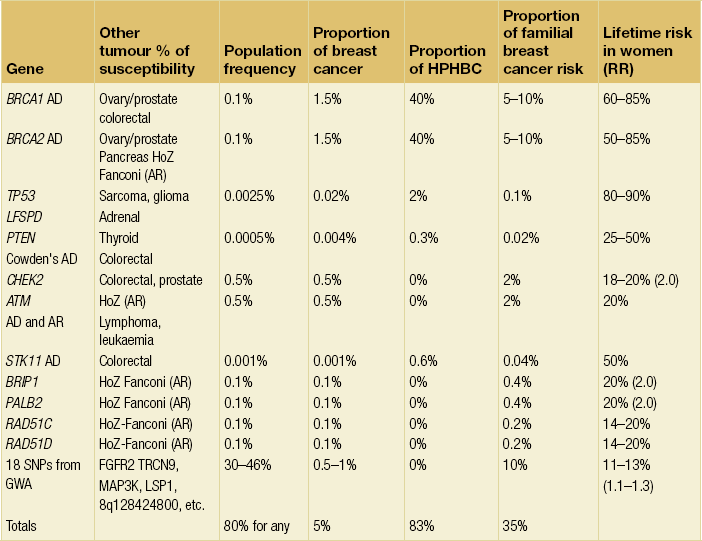

Once a mutation in a predisposing gene like BRCA1 or BRCA2 has been identified in a family, definitive genetic testing is possible. This can then more accurately inform women of their risks and give them an informed choice of different options, including risk-reducing surgery. Undertaking mutation analysis on an unaffected individual (without checking an affected relative), particularly in a breast cancer-only family, is problematic. Whilst identifying a pathogenic mutation will confirm a high risk, the absence of a mutation will not exclude the possibility that other genes or even a mutation refractory to the mutation screening techniques used are present. Although other genes are now being identified (see Table 8.1), many more remain to be found and screening for mutations is not clinically useful outside of BRCA1/2 and in certain circumstances TP53. Nevertheless, the outcomes of genome-wide association studies indicate that all breast cancer cases will carry at least one risk allele.21,22 Once all the lower risk alleles have been found a definitive genetic test can then be developed.

Breast cancer risk estimation

Where there is not a dominant family history or it is not possible to identify a mutation in BRCA1/2, risk estimation is based on large epidemiological studies, which give a 1.5- to 3-fold relative risk with a family history of a single affected relative.1,2 Clinicians must be careful to differentiate between lifetime and age-specific risks. Some studies quote a ninefold or greater risk associated either with bilateral disease in a mother or with severe atypical hyperplasia. However, these risks are time limited and if these at-risk individuals are observed for many years, their relative risk is reduced over time.23 Clearly, if one uses these risks and multiplies them against the lifetime incidence of 1 in 8–12 then some women will apparently have a greater than 100% chance of having the disease. Risks importantly do not multiply and may not even be additive. The best way to assess risk is to take the strongest risk factor, which in most cases is nearly always the family history. If risk is assessed on this alone, minor adjustments can then be made for other factors. It is arguable whether these other factors have any major effect on an 80% penetrant gene other than to speed up or delay the onset of breast cancer. Therefore, we can only really assume an effect on non-hereditary elements of risk. Although studies do point to an increase in risk in family history cases associated with certain factors, these may just represent an earlier age expression of the gene. Generally, therefore, non-mutant gene carriers will have risks somewhere between 40–45% and 8–10%, although lower risks are occasionally given. Higher risks are only applicable when a woman at 40–45% genetic risk is shown to have a germline mutation and to have inherited a high-risk allele or to have proliferative breast disease.

These programs take into consideration varying permutations of age of onset of diagnosis, number of affected and unaffected women, and hormonal factors; as a consequence, different programs result in different risk estimations. The Gail model does not take into account age of relatives or second-degree relatives. A newer model, the Tyrer–Cuzick,27 incorporates the majority of the currently known risk factors.

A major deficiency of current genetic models is the assumption that all inherited breast cancer is due to a single high-risk dominant gene or two genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2). The problem this causes in a program like BRCAPRO is that in order to obtain an accurate assessment for identifying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation in a family, all other potential genetic factors are overlooked. Therefore, while BRCAPRO provides reasonably accurate estimates for the presence of BRCA1/2 mutations in high-risk families,12 its ability to predict breast cancer incidence is substantially hampered in smaller aggregations of breast cancer. Variation in their value in different ethnicities has also been found.28–30 We have recently found that BRCAPRO underestimates the risk of breast cancer in moderate/high-risk families by about 50%.31 The most accurate computer model was the Tyrer–Cuzick model, although a manual model incorporating the Claus tables and data from the BCLC and adjustment for hormonal and reproductive factors was similarly accurate. A fuller explanation of the manual model25,31 and a detailed review32 are available elsewhere.32

Management options

Management options available to reduce the risks of developing breast cancer for women at high lifetime risk due to their family history or for those women known to be carrying a mutation in BRCA1/2 are limited. Screening with mammography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one option but this detects cancer, it does not prevent it. Therefore, imaging surveillance can be combined with chemoprevention. However, many women consider or undergo risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) if found to be at high risk, e.g. mutation carriers for BRCA1 or BRCA2. The efficacy of surgical procedures for reducing the risk of breast cancer is controversial but of proven benefit,33,34 although it would appear that the residual risk of breast cancer depends on the amount of residual breast tissue following the surgical procedure. It would be ideal to perform a prospective randomised clinical trial where women with the same risk were randomised to either intensive surveillance or prophylactic surgery, but it would be difficult to recruit women for this type of trial and so it is unlikely to happen. Recent work suggests that more women are considering RRM,35,36 although uptake rates even for BRCA mutation carriers vary enormously, with a much lower uptake in Israel and southern Europe, almost certainly due to different cultural beliefs, protocols and availability.36 Protocols should be in place to deal with requests for RRM at all cancer genetics and oncoplastic clinics. It has been suggested that surgery does increase life expectancy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers.37

Genetic counselling and the family history clinic

Breast cancer family history clinics started to be established in the UK in 1987,42,43 and these clinics are now established across Europe, North America and are now also emerging in Asia.44,45 Genetic counselling sessions and family history clinics are important not only to provide a means to select suitable individuals for genetic testing, but also to aid decision-making in individual women on surveillance and preventative measures. They are generally administered by consultants in medical oncology, clinical genetics and breast surgery, often with a multidisciplinary approach and with close involvement of radiologists and a psychiatrist/psychologist. At these clinics unaffected women at increased risk of breast cancer are assessed as to their lifetime and shorter-term risks of breast cancer development. After assessing risk, women are presented with a number of choices including regular surveillance, usually with a combination of clinical examination, mammography, ultrasonography and in some circumstances breast MRI46 that commences between 20 and 40 years depending on the age of onset of cancers in the family and the overall risk. Women are generally divided into three risk groups: average, moderate and high risk. It is only in the high-risk group that RRM should be considered. This usually equates to a lifetime risk of 1 in 4 (25%) or greater. As a rough guide, this equates to having a heterozygote risk of 1 in 4 with two relatives, including one first-degree relative, with breast cancer diagnosed below 50 years of age or three affected relatives under 60 years. All affected relatives should be first-degree relatives or related through a male.

In a survey of 10 European centres,42 only three (Manchester, Edinburgh, Heidelberg/Dusseldorf) routinely mentioned the possibility of RRM to women with a lifetime risk of 1 in 4 or greater. This information is often only given as a statement of the availability of the procedure as an option for prevention of breast cancer. This allows women to extend the discussion if they wish to do so, or to state that they are not interested in surgery. Many centres only mention risk-reducing surgery to potential mutation carriers undertaking a genetic test. Indeed, there is a cultural shift across Europe from north to south, with RRM being less acceptable to both physician and patient as one moves southward.47,48 In the USA, in centres where mastectomies for benign breast disease were commonplace in the 1970s and 1980s,38 there appears to be less enthusiasm for mastectomy now even among gene mutation carriers.49 What is absolutely clear is that adequate preparation of a woman contemplating RRM is essential.

The RRM protocol

Women who wish to consider RRM should be given time to consider the procedure thoroughly prior to making the decision. In Manchester, a protocol is in place for women who are assessed as at high risk who would be suitable for RRM despite not having certain knowledge of mutation status. For example, an individual’s calculated lifetime risk may be 40%, but a recognised gene mutation may not have been identified in the family. This exact same protocol may not be offered in other centres but the general principles of counselling apply. In general, most centres will offer multiple sessions of discussion of available surgical procedures and counselling. Most women would be offered a further appointment at least 1 month later. This not only gives the women time to consider more fully all options but also allows time for them to discuss it with appropriate members of their family. The mean time interval from a personal genetic diagnosis to the date of surgery of RRM is approximately 9 months.50 Usually the partner or a family member selected by the patient is encouraged to attend the clinic session to help decision-making. At the second appointment, with a geneticist or oncologist, a basic description of the surgery is provided, including the potential residual risk of different procedures. It is emphasised that a residual breast cancer risk and complication rates from surgery are still present after RRM and may be higher if the surgery preserves the nipple–areola complex (NAC). Options of simultaneous breast reconstruction can also be discussed. It is important to prepare the patient for the likely consequences of mastectomy including pain and any possible complications that, if they occur after breast reconstruction, may result in a poor cosmetic result, as well as considering the impact upon her personal life and family dynamics. Because of potential pitfalls such operations should only be undertaken by surgeons highly skilled in RRM and its possible complications, to optimise both oncological and aesthetic outcomes.

When possible, a living affected member should be the first to undertake genetic testing as this provides more information on the underlying genetic structure of the family.25,51,52 A time scale for genetic testing is discussed, and the woman is asked to consider the potential impact of proceeding with surgery, particularly if she then undergoes genetic testing and finds that she does not in fact carry the causative mutation. It is also emphasised that the genetic risk of breast cancer decreases with age and that the remaining risk of breast cancer if the woman is older (> 40 years) and has not developed breast cancer becomes lower than the lifetime risk.25 Indeed, a mutation carrier for BRCA1 may have no more than a 50% risk of breast cancer in her remaining lifetime if she has reached 50 years, but this is still a substantial personal risk. Psychological assessement and counselling should be arranged for women who are considering proceeding.

The whole process, from first consultation to the surgical procedure itself, usually takes between 6 and 12 months. This time delay is deliberate; in most centres the greatest delay is at the beginning of the protocol in order to allow women time for the decision-making process. If the protocol is run concurrently with a decision for predictive genetic testing, then the wait will generally be shorter. The full protocol of two sessions at the family history clinic, a session with a psychiatrist and sessions with the surgeon was established in 1993 in Manchester. The major difference between this protocol and that offered by some other centres both locally and internationally is that RRM in other centres is offered only when raised by the patient, and it is generally only offered in these centres when a woman is proven to be a BRCA1/2 mutation carrier. Even with a proven mutation carrier no centre actively recommends surgery, but offers this as part of a range of choices. The incorporation of counselling during decision-making and treatment has been shown to improve psychological and social outcome.54,55

Surgical consultation

The aim of risk-reducing surgery is not only to reduce cancer risk and breast cancer mortality, but also to reduce the psychological distress and anxiety of an individual.56 For unaffected mutation carriers RRM reduces lifetime risk of breast cancer to less than 5%.57,58 However, any surgical procedure, particularly in a preventative setting, warrants a balanced discussion of its benefits and risks. Due to lack of level I evidence from randomised controlled clinical trials, recommendations are usually based on cohort studies of prophylactic surgery.59,60 Moreover, to date, although risk of breast cancer is reduced there are still no data that show statistically significant improvement in survival after RRM. It is also important that when a women embarks on such a decision, a full understanding of the surgery involved is achieved and the woman understands that risk reduction of cancer is never 100%. Risk reduction surgery is not a minor cosmetic procedure but major surgery, and hence the nature and extent of the surgery and possible complications need to be considered. The expected cosmetic result, changes in the patient’s breast sensation and also the impact of RRM on a patient’s social life should be addressed. The whole range of evolving surgical techniques that can be offered should be discussed thoroughly before a decision is made for surgery.

In order to properly select suitable individuals for RRM, at least two detailed surgical consultations are needed to discuss the types of mastectomy and breast reconstruction procedures that are available. The techniques, limitations, outcomes and potential complications, and photographs of a range of aesthetic outcomes should be shown. It must be emphasised that there is still a small chance of getting cancer after RRM and that subjectively the breasts may look and feel different from the original breasts even if a successful surgical outcome is achieved. Time should be given for the women to digest this information. Consultations should involve a breast oncoplastic surgeon, plastic surgeon if appropriate and also a breast nurse specialist. More intimate issues including quality-of-life concerns, changes of body image and impact on sexual relationship with her partner may result in further questions following surgical consultation.61 Before discussing details of options for surgery, during the consultation session it is important to identify any women where RRM may not be advisable. There are relative contraindications to RRM taking place (see Box 8.1).

The decision of which surgical option to choose will vary between individuals (see Box 8.2).62

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree