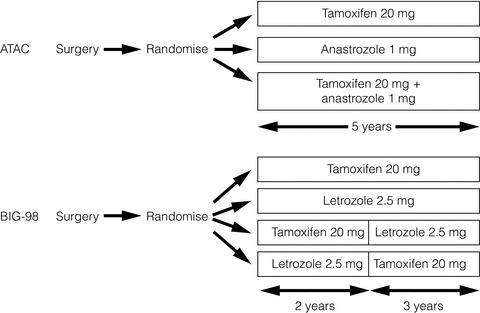

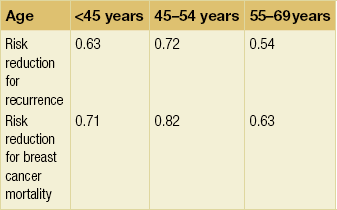

12 The mortality from breast cancer has fallen by over 15% in the UK over the last 15 years, despite a rising incidence. The improvement in survival coincides with the widespread uptake of adjuvant systemic therapy and increasing evidence of its survival benefit. The rationale for this treatment is that over half of women with operable breast cancer who receive local regional treatment alone will die from metastatic disease, indicating the presence of micrometastases at the time of initial clinical presentation. Traditionally, the major risk factors for recurrence have been the involvement of axillary nodes, poor histological grade, large tumour size and histological evidence of lymphovascular invasion around the tumour site. The absence of oestrogen and progestogen receptor and the overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) also carry an adverse prognosis. The only way to improve survival for these women is to administer effective systemic medical treatment, using endocrine therapy, chemotherapy and targeted biological therapies, along with surgery and radiotherapy. It is now recognised that breast cancer comprises a number of subtypes, each with a distinct biological behaviour and prognosis, and increasingly molecular factors rather than classical histopathological features are being used to determine the degree of residual risk after breast cancer surgery, and all the judicious use of potentially toxic treatments.1 Gene expression profiling has emerged as a new determinant of recurrence risk and a major current challenge is to assimilate this new technology into treatment planning. Approximately 75% of invasive breast cancer patients present with hormone-receptor positive disease.2 As the oestrogen receptor (ER) pathway is key to the growth of these cancers, modulation of ER activation is an essential component of treatment for these women. Since the observation by Beatson more than 100 years ago that oophorectomy could induce regression of advanced breast cancer,3 endocrine treatment has proved one of the most valuables therapies in cancer medicine. Until recently tamoxifen was the standard adjuvant endocrine therapy. The results of the most recent overview of tamoxifen trials involving around 21 000 women carried out by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) have shown that tamoxifen given for about 5 years reduces the risk of death by around one-third (relative risk (RR) = 0.71 ± 0.07).4 The proportional reduction is not significantly affected by age, nodal status or use of chemotherapy; the absolute benefit of course relates to the absolute risk. The reduction in the risk of recurrence is seen both during the 5 years of treatment (RR = 0.53 ± 0.03) and extends into years 5–9 (RR = 0.70 ± 0.06), but there was no further reduction in risk beyond 10 years. The benefits were similar and highly significant in both ER-positive/progesterone receptor (PgR)-positive and ER-positive/PgR-negative disease. The reduction was greater in strongly positive ER disease (RR = 0.51 ± 0.07) than in marginally ER-positive disease (RR = 0.65 ± 0.07). The overview data indicate that 5 years of tamoxifen is more effective than shorter durations. Until very recently, there was no convincing evidence that more than 5 years of tamoxifen had a further advantage. Indeed, the largest published trial so far of tamoxifen for more than 5 years (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B14) showed that tamoxifen for more than 5 years had an unexpected adverse influence on disease-free survival (DFS) (78% vs. 82% with placebo, P = 0.03) and was also associated with higher rates of endometrial cancer, ischaemic heart disease and cerebral vascular disease.5 Recently a much larger international trial involving 11 500 patients, the Adjuvant Tamoxifen Longer Against Shorter (ATLAS) trial, has addressed the question of long-term tamoxifen duration. Results have so far been presented only in abstract form, but showed a small but significant reduction in recurrence comparing 5 years with more than 5 years treatment (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.88).6 Preliminary results from a similar UK trial (aTTom: adjuvant Tamoxifen – To offer more?) involving 8000 patients are reported to be consistent with those of ATLAS, but mature data are awaited.7 In the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial involving over 9000 women, anastrozole was compared with tamoxifen and with a combination of the two drugs, and was shown to be superior to both in terms of DFS. With a median follow-up of 120 months, a 5-year DFS benefit of 4.3% (HR = 0.86) emerged in hormone receptor-positive patients.10 In the BIG1-98 trial involving more than 8000 women, letrozole was compared with tamoxifen in a four-arm trial as follows: letrozole monotherapy; tamoxifen monotherapy; sequential tamoxifen then letrozole; sequential letrozole then tamoxifen; all for a total of 5 years. With a median follow-up period of 8.7 years, letrozole was significantly better than tamoxifen in terms of both DFS (HR = 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 074–0.92) and overall survival (OS) (HR = 0.79, CI 0.69–0.90).11 This is in contrast to the ATAC trial, where no overall survival benefit was seen for anastrozole over tamoxifen. The results of these two trials are summarised in Table 12.1. Table 12.1 Results from the ATAC and BIG1-98 trials First-line aromatase inhibitors: bad prognosis subgroups: ER-positive, PgR-negative breast cancers are recognised as having a poorer outcome.12 In the EBCTCG analysis, patients with PgR poor tumours had a worse prognosis but nevertheless had a similar proportional benefit to adjuvant tamoxifen compared with control.4 The relative gain with anastrozole and letrozole respectively over tamoxifen is similar in both the ATAC and the BIG 1-98 trials,13 but in both instances the absolute gain is greater in patients with PgR-negative cancers, because of the greater risk of recurrence. HER-2-positive tumours have a worse prognosis than HER-2-negative cancers and in a neoadjuvant endocrine therapy trial comparing letrozole with tamoxifen, a large and highly significant benefit was seen for letrozole over tamoxifen in terms of clinical response in this small subgroup (88 vs. 21%, P = 0.0004).14 In a similar neoadjuvant trial comparing anastrozole with tamoxifen, the IMmediate Preoperative Arimidex Compared with Tamoxifen (IMPACT) trial, a numerical although non-significant difference was again seen in favour of the aromatase inhibitor for HER-2-positive tumours (58% vs. 22%, P = 0.09).15 These results were not, however, confirmed in the equivalent adjuvant trials. In the ATAC trial there was no evidence of a proportionately greater benefit for anastrozole over tamoxifen in HER-2-positive tumours compared with other subtypes.13 A similar finding was true when letrozole was compared with tamoxifen in the BIG1-98 trial.16 Invasive lobular cancers appear to benefit more from letrozole than tamoxifen.17 Comparative toxicities of front-line anastrozole/letrozole and tamoxifen: The ATAC and BIG1-98 trials have both shown that tamoxifen is associated with a small but significant increase in the incidence of hot flushes compared with anastrozole or letrozole (4.5–5% increase), vaginal bleeding (3.3–3.7% increase), vaginal discharge (8.6% increase), endometrial carcinoma (0.2–0.4% increase) and venous thromboembolism (1.4–2% increase). The ATAC trial has likewise shown a small but significant increase in ischaemic cerebral vascular disease (1.1% increase) with tamoxifen compared with anastrozole, but this has not been confirmed in the BIG1-98 trial with letrozole. In contrast, anastrozole and letrozole have been shown to be associated with a statistically significant increase in the incidence of musculoskeletal problems (6.5–8% increase) and fractures (1.7–2.2% increase). Of note, tamoxifen is associated with a significant increase in gynaecological surgery compared with either of the aromatase inhibitors. In the ATAC trial 5.1% of women had hysterectomies compared with 1.3% on anastrozole.18 In the BIG1-98 trial 288 women (9.1%) have required endometrial biopsies compared with 77 (2.3%) with letrozole.9 Until recently, there was considerable interest in trials assessing the benefit of sequential adjuvant aromatase inhibitors given 2–3 years after tamoxifen. For example, in the Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES), 4274 patients who had already been on tamoxifen for around 2 years were randomised double-blind to continuing on tamoxifen or switching to exemestane to complete 5 years of treatment. Updated results with a median follow-up of 91 months have shown a significant reduction in the risk of relapse and an improvement in OS (HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.75–0.99) with the switch.19 Three other sequential trials involving anastrozole have shown similar results.20–22 Two trials have addressed this issue directly, however, and recently reported results. Two of the arms in BIG1-98 compared tamoxifen for 2 years followed by a switch to letrozole with letrozole alone for 5 years and found no significant benefit of the switch compared with letrozole up front (8-year DFS 85.9% vs. 87.5%).11 Likewise, in the TEAM (Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational) trial, 9779 patients were randomised to tamoxifen for 2–3 years followed by exemestane to complete 5 years or to exemestane up front for 5 years. No significant difference was found in DFS (85% vs. 86%) with a median follow-up of 5.1 years.23 The risk of recurrence of early breast cancer continues for at least 10 years after diagnosis and is greater in patients with hormone receptor-positive cancers.24 In the EBCTCG overview analysis more than half of breast cancer recurrences occur after the 5-year mark.4 Against this background, the results of the MA17 trial evaluating the benefit of extended adjuvant therapy with letrozole in women still in remission after 5 years of tamoxifen were of great importance in that they demonstrated a significant DFS benefit in favour of letrozole.25 This benefit has continued, and indeed increased with time, with an initial HR of 0.52 (95% CI 0.40–0.64) 12 months after randomisation, increasing to 0.19 (0.04–0.34) after 48 months. Recently a similar and perhaps even greater benefit has been reported for the subgroup of 889 younger women < 50 and premenopausal at the time of diagnosis but who subsequently became postmenopausal during their 5 years of tamoxifen, with an absolute gain in 4-year DFS of 10%.26 This represents a risk reduction of 75% with extended adjuvant endocrine therapy compared with 33% in the much larger group who were postmenopausal from the outset. In two similar but smaller trials, extended adjuvant anastrozole (ABCSG-6a) and extended adjuvant exemestane (NSABP-B33), both after 5 years of tamoxifen, showed that extended therapy with an aromatase inhibitor reduces the risk of recurrence significantly.27,28 Aromatase inhibitors are contraindicated in premenopausal women. Likewise, caution must be observed in their use in younger women following chemotherapy-induced amenorrhoea. In an audit carried out at the Royal Marsden Hospital 12 of 45 younger women (27%), median age 47, treated with an aromatase inhibitor following chemotherapy-induced amenorrhoea (27%) developed clinical or biochemical return of ovarian function (including up to the age of 53 years).29 Aromatase inhibitors should therefore be used with great caution in this group of women and ideally serum oestradiol should be monitored using a high sensitivity assay. Vaginal dryness, atrophy and dyspareunia are significant issues in women on aromatase inhibitors. In a small study, six of seven women given vaginal oestradiol (Vagifem®) while on an aromatase inhibitor developed a significant rise in serum oestradiol from less than 5 pmol/L to a mean of 72 pmo/L (maximum 219 pmol/L) at 2 weeks.30 A key question is whether ovarian suppression in addition to tamoxifen (and chemotherapy where appropriate) is superior to tamoxifen alone in the management of premenopausal breast cancer. In the INT-101 trial, the addition of goserelin and tamoxifen to standard adjuvant therapy with CAF (cyclophosphmide, adriamycin and fluorouracil) significantly improved DFS; 9-year DFS rates were 57% for CAF, 60% for CAF plus goserelin, and 68% for CAF plus goserelin and tamoxifen.31 An unplanned retrospective analysis of these data suggested that the addition of goserelin to CAF was most beneficial in those women under the age of 40. A prospective trial, SOFT (Suppression of Ovarian Function), is currently addressing this question and has recruited 3000 premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive disease randomised to tamoxifen alone for 5 years or ovarian suppression with either tamoxifen or exemestane for 5 years in women post-chemotherapy who are still menstruating, or who have not received chemotherapy. It is currently in active follow-up. In a randomised trial involving 927 premenopausal women, no significant differences in risk reduction were seen after 12 years of follow-up between tamoxifen alone (27%) or a combination of tamoxifen with the luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogue goserelin (24%).32 The SOFT trial also addresses the important question of whether an aromatase inhibitor is superior to tamoxifen in premenopausal patients who have undergone ovarian suppression. The only trial to present data on this so far is ABCSG-12 and the Austrian Group reported no significant difference in outcome for 1803 women randomised to tamoxifen or anastrozole, both given with goserelin, with a median 62 months follow-up.33 An increase in body mass index is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence34,35 and this was recently confirmed in patients in the ATAC trial.36 Moreover, the benefit of anastrozole over tamoxifen in terms of distant recurrence was lost in patients with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater, and a similar trend was seen for all recurrences. The Austrian ABCSG-6 and -6a trials in which patients who had maintained a continued remission on tamoxifen for 5 years were randomised to a further 3 years of anastrozole or not have reported similar findings. Outcome was not influenced by body weight during tamoxifen therapy, but during extended adjuvant therapy an exploratory analysis found that women with normal body weight randomised to anastrozole had a significant gain in DFS (HR = 0.46, P = 0.02) and OS (HR = 0.37, P = 0.02), whereas no gain was seen in patients with a body mass index of greater than 25 kg/m2.37 This raises the intriguing possibility that anastrozole, a relatively weak aromatase inhibitor, is unable to inhibit fully the excess aromatase associated with adiposity. In contrast, in the BIG 1-98 trial, the benefit of letrozole, a much more potent aromatase inhibitor than anastrozole, over tamoxifen was maintained whatever the body mass index.38 Further data are required, but these results suggest that anastrozole may not be the optimal aromatase inhibitor in women with higher body mass indices. See Table 12.3 for a summary of recommendations for adjuvant endocrine therapy. Table 12.3 Summary of recommendations for adjuvant endocrine therapy *Based on pre-chemotherapy menopausal status. †Caution in women under the age of 50; return of ovarian function on aromatase inhibitor is possible. In general, the absolute gain from chemotherapy is higher for younger than older women.39 It is likely, however, that this difference relates mainly to the biological characteristics of breast cancer being more favourable to chemotherapy response (ER negativity, for example) in younger women, rather than an intrinsic adverse interaction between age and chemotherapy efficacy.41 Elderly women with breast cancer have been under-represented in clinical trials to date, but this is changing. The Cancer and Leukaemia Group B (CALGB) 49907 trial demonstrated that standard adjuvant chemotherapy was superior to single-agent oral chemotherapy with capecitabine in women over the age of 65, and suggested that the benefit was more pronounced in women with hormone receptor-negative tumours.42 However, it is also clear that older women experience significantly greater toxicity with adjuvant cytotoxic treatment,43–46 and there are a number of trials under way that aim to define those elderly patients for whom chemotherapy is most appropriate. Initially adjuvant chemotherapy tended to be reserved for patients with axillary node involvement on the basis of higher risk. It is now clear that the proportional reduction in the risk of recurrence is similar for those with node-negative as for node-positive disease.39 Nevertheless, since the absolute risk is greater with nodal involvement, so is the absolute benefit. Although nodal involvement carries a worse prognosis, this does not necessarily imply chemotherapy benefit and we are now in an era when molecular markers are at least as important as nodal status in determining chemotherapy benefit (see below). There has been considerable controversy over the years as to whether patients with ER-positive disease gain as much from adjuvant chemotherapy as those whose tumours are ER negative. The 2011 Oxford Overview data indicate that the proportional benefits are very similar, both in older and younger women.39 Anthracyclines have been used widely for the last decade or more, and have largely replaced older CMF (cyclophosphamide/methotrexate/fluorouracil) regimens. The 2005 Overview data (including trials involving a total of around 40 000 women) established clearly the efficacy of anthracycline-based adjuvant regimens in early breast cancer, and indicated an additional proportional risk of recurrence of around 11% and a proportional reduction in mortality of around 16%.47 The two main anthracyclines in current use are adriamycin (doxorubicin) and epirubicin. The Cancer and Leukaemia Group B (CALGB) 9344 trial randomised women with node-positive breast cancer to receive four courses of anthracycline chemotherapy to one of three different adriamycin dose levels (60, 75 or 90 mg/m2), followed by four cycles of paclitaxel or not.52 This important dose escalation trial showed no benefit for adriamycin doses above 60 mg/m2 and this dose should now be considered standard. The French Adjuvant Study Group (FASG)-05 trial randomised lymph node-positive women with poor prognosis and found a dose effect in favour of six cycles of FEC100 (epirubicin 100 mg/m2) over six cycles of FEC50 (epirubicin 50 mg/m2).53 A significant improvement in the DFS (66.3 months vs. 54.8 months) and 5-year OS (77.4% vs. 65.3%) was seen in the FEC100 group but there were significantly more side-effects in the FEC100 group. These included neutropenia, anaemia, nausea and vomiting, stomatitis, alopecia and grade 3 infections. It is important to note that this trial does not determine that an epirubicin dose of 100 mg/m2 is optimal. All that can be concluded is that 50 mg/m2 is suboptimal and that a dose between the two is likely to achieve the best balance between efficacy and toxicity. In the 2011 Oxford meta-analysis, four cycles of anthracycline chemotherapy appeared equivalent to six courses of standard CMF, but there was a clear improvement in recurrence and mortality when regimens with a cumulative anthracycline dosage of more than 240 mg/m2 adriamycin or 360 mg/m2 epirubicin (for example, fluorouracil/adriamycin/cyclophosphamide (FAC) or FEC) were compared with CMF (risk ratio 0.89 and 0.84 for recurrence and mortality respectively).39 Higher doses of anthracylines are related to long-term complications such as an increased incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)/myelodysplasia. In the EBC-1/MA.5 study by the NCIC CTG, which used the very high epirubicin dose of 120 mg/m2, a disturbingly high incidence of AML/myelodysplasia was reported (2% at 10-year follow-up).50 Likewise, in a study that analysed the toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in elderly patients, there was a linear increase in the incidence of AML/terms of recurrence-free survival (P < 0.001) with a reported incidence of 1.8% for the group of age > 65 years.43 Cardiotoxicity is a further concern with the anthracyclines. Symptomatic congestive heart failure (CHF) is a rare but very serious complication in patients receiving an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen with an incidence that relates to the cumulative dose received.54,55 As with secondary AML, there is an association between the risk of cardiotoxicity and increasing age. Recent long-term data on cardiac safety in more than 40 000 early breast cancer patients of an older age treated with adjuvant anthracycline regimens have shown an increased risk of cardiotoxicity compared with non-anthracycline chemotherapy treatment. This was statistically significant in the group of patients aged 66–70 with a 26% increased risk of developing CHF. This difference in rates of CHF continued to increase through more than 10 years of follow-up.45 The CALGB 8541 trial reported in 397 node-positive patients that high expression of HER-2 was associated with benefit from standard doses of doxorubicin (60 mg/m2) but not from lower doses of anthracyclines.56 In contrast, this dose–response effect was not seen in the majority whose tumours did not overexpress HER-2. An additional cohort of 595 patients showed an even stronger correlation between HER-2 overexpression and CAF dose efficacy with further follow-up.57 No significant interaction was observed in the CALGB 9344 study between HER-2 status and the use of doses of doxorubicin > 60 mg/m2.58 In a retrospective study of 639 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens obtained from 710 premenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer who had received either cyclophosphamide, epirubicin and fluorouracil (CEF) or CMF, HER2 amplification or overexpression was associated with a poor prognosis regardless of the type of treatment. In patients whose tumours showed amplification of HER2, CEF was superior to CMF in terms of recurrence-free survival (RFS) (HR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.34–0.80; P = 0.003) and OS (HR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.42–1.02; P = 0.06).59

The role of adjuvant systemic therapy in patients with operable breast cancer

Introduction

Adjuvant endocrine therapy

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen duration

Aromatase inhibitors

ATAC*

BIG1-98*

No. of patients

6241

8010

Median follow-up (years)

10

8.7

DFS (hazard ratio)

0.91

0.82

5-year DFS difference (%)#

2.7

3.1

OS (hazard ratio)

0.97†

0.79

Sequential therapy with aromatase inhibitors after tamoxifen

Extended adjuvant therapy with aromatase inhibitors

Other aromatase inhibitor issues

Endocrine therapy in premenopausal women

Obesity and adjuvant endocrine therapy

Menopausal status*

Recommendation

Premenopausal

Tamoxifen 5 years

Postmenopausal†

Anastrazole 5 years

or

Letrozole 5 years

Women who are menopausal after 5 years of tamoxifen

Consider:

Anastrazole

Letrozole

Exemestane

in high-risk patients

Women who have completed 5 years of aromatase inhibitor

Currently no data

Consider option of continuing in high-risk patients

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Age and chemotherapy

Nodal status

ER status

Anthracycline-based chemotherapy

Dose of anthracyclines

Anthracyclines and HER-2-positive disease

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The role of adjuvant systemic therapy in patients with operable breast cancer