Tensor Fascia Lata Flaps for Trochanteric Ulcers

Terri A. Zomerlei

Jeffrey E. Janis

DEFINITION

Trochanteric ulcers are common in chronically bed-bound patients who lie in the lateral position.

Patient populations most at risk include those in acute care settings, nursing home patients, paraplegic populations and those with hip flexion contractures.

In addition to unrelieved pressure, other contributing factors include incontinence/moisture, friction/shear force, and altered sensory perception.

Characteristically, the appearance of the overlying skin only represents a small portion of the affected tissue (“the tip of the iceberg”).

ANATOMY

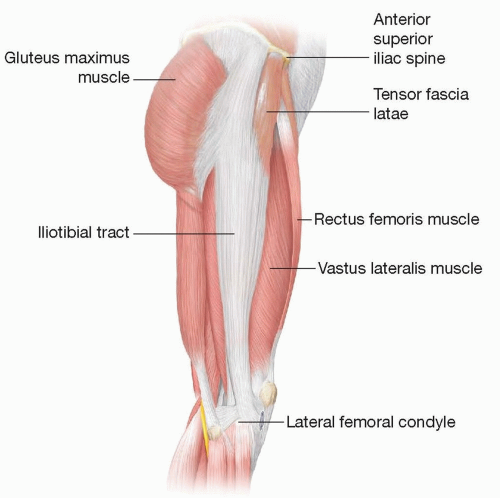

The tensor fascia lata (TFL) is a thin, bandlike muscle located in the lateral thigh just distal to the greater trochanter. It functions as a lateral knee stabilizer (FIG 1).

Rectus femoris borders anteriorly

Biceps femoris borders posteriorly

Size: The muscle is 5 cm wide, 12 cm long, and 2 cm thick.

Origin: Anterior 5 cm of the lateral lip of the iliac crest and the lateral aspect of the anterosuperior iliac spine (ASIS). A small portion also originates from the greater trochanter.

Insertion: The fascia lata is an extension of the TFL and inserts into the lateral condyle of the tibia.

The aponeurosis of the superficial potion of the gluteus muscle, the aponeurosis of the TFL and the fascia lata are commonly referred to as the iliotibial tract.

When the iliotibial tract is taut, the knee is held in extension.

When tense, the iliotibial tract also stabilizes the hip and knee while standing.

Harvest of the TFL flap is associated with minimal functional morbidity.

The TFL flap is a type I muscle with one dominant pedicle, the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA).

The LCFA is a branch of the profunda femoris.

The LCFA passes deep to the sartorius and rectus femoris.

It gives rise to three branches: the ascending, the transverse, and the descending branches that supply the superior, mid, and inferior portions of the TFL respectively.

Two venae comitantes travel with the LCFA and join the femoral vein.

The TFL receives its motor supply from the superior gluteal nerve, which has contributions from L4, L5 and S1. It enters the muscle in the middle third on the posterior aspect.

The TFL sensory nerve supply is from the lateral cutaneous branch of T12, which provides sensory innervation to the most superior aspect of the muscle and its overlying skin.

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve with contributions from L2 and L3 innervates the remaining portion of the skin and muscle.

PATHOGENESIS

Primary mechanism of pressure ulceration is cellular ischemia.

Tissue pressure higher than the pressure of the microcirculation (32 mm Hg) causes ischemia.

If the ischemic period is long enough and repeated frequently, the eventual outcome is tissue necrosis.

Pressure sores (decubitus ulcers) almost invariably occur in the tissue over bony prominences in persons not able to change body position frequently.

Pressure sores overlying the greater trochanter are common in those with hip flexion contractures who lie in the lateral position.

In acutely ill patients, third-space fluid pressure may mechanically compromise the microvasculature.

Etiologic considerations can be divided in extrinsic and intrinsic factors.

Extrinsic factors: Primarily mechanical forces of the soft tissues

Friction: Resistance that a surface encounters when moving over another. Most often occurs with patient transfers

Moisture: Incontinence can lead to skin breakdown.

Pressure: Mechanical force that is applied perpendicular to a plane (ie, between a bony prominence and a chair or bed)

Shear: Mechanical stress parallel to the plane results in stretching and compression of the blood supply to the muscles and skin.

Intrinsic factors: Patient factors that affect the soft tissues.

Altered level of consciousness: Results in lack of voluntary movements and protective reflexes that off-load pressure

Anemia: Can result in fatigue and weakness which can contribute to and perpetuate immobility. Also affects wound healing capabilities.

Autonomic control: Decreased levels result in spasms, perspiration with increased skin moisture, blood vessel engorgement and resulting tissue edema, and problems with bowel and bladder control.

Age: Increasing age is associated with increased skin friability and decreased tensile strength.

Infection: Profoundly impairs wound healing abilities

Inflammation: Creates a hostile local milieu resulting in impaired healing, especially in the setting of chronic wounds

Malnutrition: Results in wasting and decreased muscle bulk and impairs wound healing abilities

Sepsis: Can result in decreased tissue perfusion and ischemia

Sensory loss: Patient is unable to experience the discomfort associated with prolonged pressure over prominences

NATURAL HISTORY

Pressure sores are categorized according to the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Stages (NPUAP 2016).

Pressure sore can progress through the following stages if extrinsic and intrinsic insults are not remedied (see FIG 2 in Chapter 29).1

Stage I: Intact skin with nonblanching erythema

Stage II: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis

Presents as blister, abrasion, or shallow open ulcer

Stage III: Full-thickness skin loss

Subcutaneous fat may be exposed.

Tunneling and undermining may be present.

Stage IV: Full-thickness skin and tissue loss

Unstageable: Full-thickness skin or soft tissues loss but depth is unknown usually due to the presence of an overlying eschar

Suspected deep tissue injury: Persistent deep red, maroon, or purple discoloration of intact skin may indicate deep tissue injury that needs to evolve prior to staging.

PERTINENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The preoperative evaluation of patients with pressure ulcers includes a detailed assessment of the patient’s medical history, social situation, baseline health status, and a comprehensive wound evaluation.2

Patient history

How long has the ulcer been present? Acute wounds may respond to conservative treatment while chronic wounds tend to be more recalcitrant.

What is the current wound care treatment? Changing local wound care regimens may help with improving the wound.

What surgical options have been tried in the past? Obtain any and all operative reports as previous surgeries may limit surgical options.

Is the patient ambulatory, wheelchair bound or bed bound?

What type of mattress and turning regimen is currently being used? Airflow mattresses offer the best protection while normal mattresses offer little defense against pressure.

Is fecal contamination a problem? A dressing or a temporary diverting ostomy may be prudent.

Are there problems with urinary incontinence? Does the patient require temporary or permanent urinary diversion?

Does the patient have spasms? Are their medications optimized to control spasms?

Does the patient have any fixed contractures?

What is the baseline nutritional status of the patient?

Social history is crucial to obtain in order to understand possible postoperative barriers to care and to prevent recurrence.

Social support/caregiver situation

Resources for obtaining durable medical equipment (low air loss bed, seat cushion if bed bound or wheelchair bound)

Smoking or substance abuse history

Active or prior nicotine use increases risk of poor wound healing.

Consider urine cotinine testing.

Psychiatric illness

Diet, specifically amount of protein intake

Compliance history

Laboratory studies

Complete blood count to assess for anemia or active infection

Albumin, prealbumin, and total protein to assess protein stores

Coagulation panel to assess for coagulopathies

Cultures that should be obtained with tissue or bone biopsies as wound swabs have little value due to chronic colonization. Cultures should be sent for quantitative analysis and if the organism count is greater than 105, consideration should be given to systemic antibiotics and/or staged debridement and reconstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree