Factors influencing the need for transfer of thermally injured patients

Pre-hospital factors

Experience treating burn injuries

Knowledge of the treatment of burn injuries

Resources for treating burn injuries

Specialized intensive care/resuscitation requirements

Injury factors

Burn size, depth and location

Airway involvement/inhalation injury

Type of burn injury (e.g. flame, chemical and electrical)

Concomitant injuries

Need for urgent surgical intervention (e.g. escharotomy, fasciotomy, laparotomy)

Need for eventual surgical intervention (e.g. burn excision and grafting)

Patient factors

Age

Medical/psychiatric co-morbidities

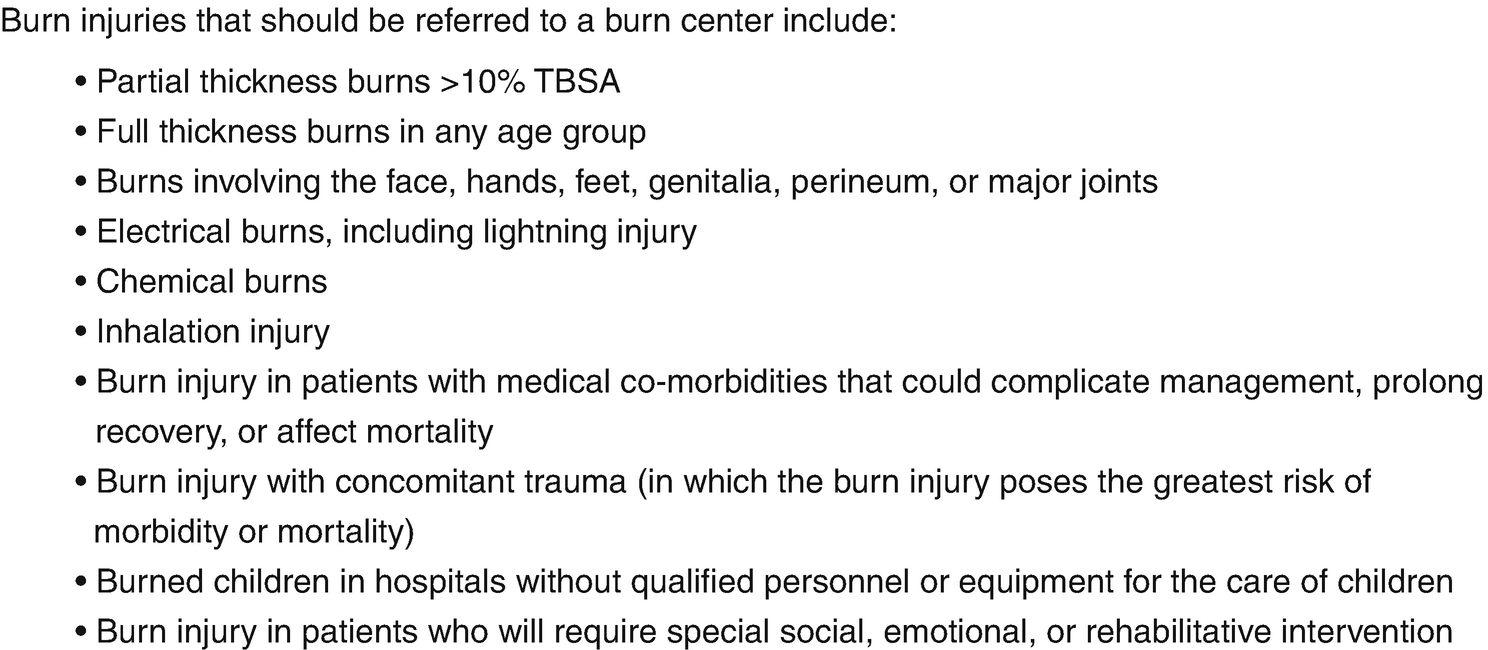

12.2.1 Pre-hospital Referral Guidelines

Inhalation injury/airway compromise

Burn size sufficient to require formal fluid resuscitation or intensive care monitoring

>10% total body surface area (TBSA) in children

>20% TBSA in adults

Complex burn mechanism (e.g. chemical burn, electrical burn)

Need for urgent surgical intervention (e.g. escharotomy)

Nevertheless, each thermal injury presents a unique set of patient-specific and injury-specific factors which must be taken into consideration as part of the transfer decision-making process.

12.2.2 The Transfer Decision

Once the pre-hospital healthcare provider decides that a thermally injured patient may benefit from transfer to a burn centre, the next step is to establish direct communication with a burn care provider at a burn centre. The burn care provider will be able to review the circumstances of the thermal injury, as well as guide the pre-hospital provider regarding the management and ongoing resuscitation of the patient. Given the complex nature of burn injuries, direct communication between the most responsible healthcare providers is of the utmost importance to ensure that information is relayed clearly and accurately. Based on this information, the burn care provider will then be able to make a final determination regarding patient disposition and the need for acute transfer. The decision to transfer a thermally injured patient is not one that should be made by a pre-hospital healthcare provider unaided.

Thermal injuries are complex by nature and may be overwhelming to healthcare providers unaccustomed to managing these injuries. In fact, the literature has documented that most pre-hospital healthcare providers have limited training and experience in treating thermally injured patients due to a lack of formal burn education during both medical school and residency training [9–12]. A study by Vrouwe et al. (2017) of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine resident physicians, at a university training program associated with a regional burn centre, found that these primary care trainees encountered on average only 1–5 thermally injured patients during training and had limited to no burn-specific didactic or clinical teaching during their training. As a result, these primary care trainees self-reported being uncomfortable in the diagnosis and management of thermally injured patients [12].

Therefore, if primary healthcare providers are not being adequately trained or exposed to thermal injuries during training, it is not surprising that these providers have been well-documented to be significantly less accurate than burn care providers in the assessment of burn injuries (i.e. burn size and depth) [13–19]. Pre-hospital healthcare providers have a tendency to overestimate the size of small burns (<20% TBSA) and underestimate the size of large burns (>20% TBSA) [13, 14, 19, 20]. These errors in burn size estimates can be significant, with discrepancies as large as 560% of actual burn size reported in the literature [21]. Unfortunately, these inaccuracies regarding burn size estimation are further propagated by their direct impact on fluid resuscitation, as most resuscitation formulae are based on weight and %TBSA involvement [14, 20, 22–24].

Furthermore, the assessment and management of the airway by pre-hospital healthcare providers in burn-injured patients has come under increasing scrutiny. Multiple studies have demonstrated a tendency towards premature intubation of thermally injured patients in the pre-hospital setting. Though prophylactic intubation may seem benign, erring on the side of precaution, this intervention is not without its own inherent risks [25]. Studies have shown that among patients transferred to a burn centre having been intubated at a pre-hospital site, 30–60% are extubated within 24 h of arrival [21, 26–28].

In addition to %TBSA estimation and airway management, significant deficiencies have been reported in regard to pre-hospital documentation of treatment for thermally injured patients. Reviews of pre-hospital transfer records have found that documentation of burn size assessment, burn depth assessment, analgesia, tetanus status, and information for referral and follow-up are commonly inadequate or missing [29, 30].

These aforementioned errors in the initial assessment of burn injuries present a unique issue for the care of thermally injured patients. As a burn care provider, this highlights not only the importance of communication with pre-hospital healthcare providers to ensure accurate assessments prior to transfer but also the potential role for outreach and education on the management of thermally injured patients for pre-hospital healthcare providers.

12.2.3 Overtriage in Burn Transfers

As previously mentioned, not all thermally injured patients require acute transfer to a burn centre. An important aspect of ensuring appropriate utilization of burn centre resources involves minimizing the number of acute transfers for burns that could otherwise be managed on an outpatient basis. These patients, when transferred acutely with injuries that do not require burn centre admission, have been labelled in the literature as ‘unnecessary’, ‘avoidable’ or ‘overtriaged’ transfers.

Lack of immediate transportation back to home community

Lack of housing in home community

Need for ongoing hospitalization for non-burn medical/psychiatric co-morbidities

By transferring these patients away from their home community, they are distanced from family and social supports. It also becomes much more difficult to arrange the supports required for repatriation. A study by Austin et al. (2017) found that among overtriaged transfers, average burn centre length of stay was 2.8 days despite average burn size of only 5% TBSA [8].

Another issue with overtriage is the costs associated with transfer, both to the healthcare system and directly to the patient. Acute transfers for thermally injured patients can be quite expensive (see 12.4.4 Cost of Burn Transportation). In many cases, if hospitalization is not required, then the patient and their family are responsible for repatriation to the home community, which can be quite inconvenient [30]. In some cases, the patient may even be responsible for the costs of the transfer, which can be more expensive than the cost of the avoidable hospitalization [21, 31, 32].

Overtriage is an accepted risk in the management of acute thermal injuries, largely due to the potential risks of undertriage (i.e. not transferring burn-injured patients that require burn centre care). However, the issue becomes the rate at which overtriaged transfers occur for thermally injured patients. Studies have demonstrated that 17–30% of patients acutely transferred to a burn centre for thermal injuries were later deemed unnecessary [8, 31–33]. Latifi et al. (2017) investigated the reasons for burn centre transfer at a single institution and found that 45% of referrals to a single burn centre were made at the request of a patient or their family, while only 43% were referred due to a need for treatment at a burn centre [34].

Inadequate knowledge of burn care

Insufficient experience providing burn care

Inadequate resources to provide burn care

Incorrect initial assessment of burn injury

As a burn care provider, it is important to recognize these factors and identify their potential influence on transfers, so as to minimize the effects of overtriage. It is also important to make efforts to overcome these barriers whenever possible. During the transfer discussion, it is important to provide the pre-hospital healthcare provider with support and guidance and to appreciate that the pre-hospital healthcare provider managing a burn patients may be overwhelmed or limited by inadequate resources. Furthermore, the value of local and regional education and outreach initiatives cannot be overstated, to ensure that pre-hospital healthcare providers have the knowledge required to treat these complex patients.

12.3 Telemedicine in Pre-hospital Burn Care

The interaction between pre-hospital healthcare provider and burn care specialist is an integral part of the transfer process. Perhaps the most important aspect of this interaction is ensuring the accuracy of information conveyed about the burn injury itself, as this can directly impact patient care. Traditionally, this interaction would occur via telephone. While this real-time form of communication provides a direct connection between providers, it is limited by its reliance solely on the assessment and verbal description of the burn by the pre-hospital healthcare provider. Given the highly visual nature of burn injuries, providing a burn specialist the opportunity to visualize the burn injury would allow for a more reliable initial assessment. In recent years, advances in technology have made this possible with the integration of telemedicine into acute burn care.

12.3.1 Definition of Telemedicine

Any technology that allows healthcare providers to connect across a distance can be classified as ‘telemedicine’. According to the World Health Organization, the official definition of telemedicine is “the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information […] in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities” [35]. This definition, though seemingly vague and broad, allows for the constant technological advancements that have changed the way medicine is practiced in the twenty-first century.

For the purposes of this chapter, however, the discussion of telemedicine focuses solely on those technologies that allow for the transmission of visual media (i.e. photographs and video) in the care of thermally injured patients.

12.3.2 Image Transfer in Telemedicine

Image transfer in telemedicine can be can be divided into two major categories, depending on the timing of the interaction between healthcare providers. In synchronous or ‘real-time’ telemedicine, individuals are simultaneously present for the exchange of information (e.g. videoconference). In asynchronous or ‘store-and-forward’ telemedicine, pre-recorded information is exchanged between individuals at different times (e.g. images sent via e-mail). In both synchronous and asynchronous telemedicine, information may be shared by any form of media (i.e. text, audio, photograph, video) [35].

Both categories of telemedicine have their advantages and disadvantages. While synchronous telemedicine provides real-time interaction between providers, establishing this live connection requires all parties to be available at the same time, and there must be access to a fast and reliable telecommunication network. On the other hand, while asynchronous telemedicine may have a delay in the interaction between providers, these connections are easier to arrange with less reliance on advanced telecommunication networks, and the ability for providers to review information at their leisure. For these reasons, asynchronous technology is the more commonly used method of communication for telemedicine in acute burn care [4].

12.3.3 Evidence for Telemedicine in Acute Burn Care

Assessment of inhalation injury and the need for intubation

Assessment of burn size and depth

Assessment of need for fluid resuscitation

Assessment of need for surgical intervention

As previously mentioned, errors in the initial assessment of burn injuries by pre-hospital healthcare providers can significantly impact patient care. Saffle et al. (2004) found that 35% of patients transferred to a single burn centre would have had a substantial alteration in their care had telemedicine been available prior to transfer [21]. Multiple studies have shown high rates of potentially avoidable intubation among burn-injured patients, with 30–60% of patients intubated prior to transfer able to be safely extubated within 24 h of transfer [21, 26–28]. Furthermore, a prospective study by Wibbenmeyer et al. (2016) found that burn-injured patients transferred from referring centres that provided video images of the injuries prior to transfer had a significantly lower incidence of over- or under-resuscitation compared to referring centres that only had telephone communication [18]. By confirming the accuracy of initial burn injury assessment, telemedicine can help to prevent potential complications arising from primary assessment errors.

Second, telemedicine can improve the triage accuracy for acute thermal injuries, allowing for more informed transfer decisions and minimizing the effects of overtriage. Allowing a burn care provider to see images of a burn injury prior to deciding on the need for transfer improves confidence in the triage decision-making process. In situations where visual documentation is unavailable, there is a natural tendency to err on the side of caution so as to reduce the risk of undertriage. Wallace et al. (2007) found that the implementation of a telemedicine program for burns reduced the rate of unplanned clinic admissions from 21% down to 0% [37]. Den Hollander et al. (2017) found that the use of telemedicine led to an alteration of the transfer plan in 66% of referrals, with 38% of transfer referrals being avoided completely during an 8 month study period [38]. Saffle et al. (2009) demonstrated that the implementation of a regional telemedicine program altered the transfer plan in 55% of patients, with 42% of transfer referrals that would have previously required air transport able to receive local treatment only and another 12% able to be transported by private vehicle instead of by air [39]. Russell et al. (2015) were able to decrease air transport rates from 100% to 44% with the implementation of a telemedicine program [40].

As technology has improved and the potential benefits of telemedicine have been recognized, use of telemedicine in acute burn care has increased significantly. A 2012 study found that 84% of burn centres in the United States were using telemedicine, with the majority of centres reporting telemedicine use on a regular basis for both acute burn consultation and to aid in the determination of need for acute burn transfer [4]. Successful telemedicine programs have been implemented in both developed and developing nations, as well as cross-border international programs [38, 40–44]. These telemedicine programs have repeatedly demonstrated a high satisfaction rating among referring providers and patients [18, 37, 39, 40]. In 2017, the American Telemedicine Association developed guidelines for the establishment of a Teleburn network, which can aid in the development and implementation of telemedicine programs [5].

12.3.4 Accuracy of Burn Assessment Using Telemedicine

One of the key features required for the adoption of telemedicine in burn care is that the technology must allow burn care providers to accurately assess burn injuries, both in terms of burn size and burn depth.

Telemedicine has repeatedly demonstrated both high reliability and validity compared to in-person assessment for the estimation of burn size [39, 40, 45, 46]. Saffle et al. (2009) compared burn size estimates performed by burn physicians via telemedicine to in-person estimates and found high correlations [39]. Shokrollahi et al. (2007) demonstrated high intra- and inter-rater reliability comparing telemedicine evaluation to in-person evaluation of burn size [46]. Hop et al. (2014) compared burn size estimates made via telemedicine to laser Doppler imaging of burn size and again demonstrated good inter-rater reliability and validity for the determination of burn size [45]. Even in dark skin types, telemedicine is at least as accurate as in-person evaluation of burn size [15]. However, when it comes to the assessment of burn size via telemedicine, experience does appear to play a role, with senior burn care providers being more accurate at estimation compared to providers with fewer years of experience [45].

In regard to the estimation of burn depth, the results of telemedicine have been slightly more mixed. While telemedicine can be used to distinguish full-thickness from partial-thickness burn injuries with a high degree of accuracy, determining the depth of partial-thickness burns (i.e. deep partial-thickness versus superficial partial-thickness) can be more difficult [46]. Boccara et al. (2011) reported that photographic evaluation of burn depth was equivalent to in-person assessment in 76% of cases, with most errors occurring amongst burns of intermediate depth [47]. Jones et al. (2003) also found that agreement on the depth of partial-thickness burns amongst four independent observers was lower than for either full-thickness or superficial burn injuries [47]. Boissin et al. (2015) found that amongst dark skin types, burn depth could be accurately assessed via telemedicine in 66% of cases [15]. In general, there seems to be a tendency to overestimate the depth of partial-thickness injuries when assessed via telemedicine [45]. Conversely, a study by Jones et al. (2005) found that inter-rater correlation of burn depth assessment ranged widely, from poor to good [46]. Hop et al. (2014) suggested that burn depth assessments via telemedicine were unreliable when compared to laser Doppler imaging assessment, though this technology is much more sensitive than clinical assessment alone [45]. However, it is important to remember that even experienced burn care providers only have a 50–76% accuracy rate for in-person determination of burn depth [17, 45].

Overall, telemedicine can be used to accurately assess thermal injuries for the purposes of initial management and triage. However, caution should be exercised if planning to use telemedicine alone to determine a clinical treatment plan, particularly if this plan is based on the assessment of burn depth. Hop et al. (2014) found that telemedicine alone could not be used to accurately determine the need for surgical debridement in small burn injuries (<10% TBSA) [45]. In situations where there is question about the need for potential surgical intervention, close follow-up and re-evaluation should be considered to monitor burn wound evolution over time.

12.3.5 Image Quality in Telemedicine

For accurate image assessment to occur via telemedicine, the image files must be of sufficient quality. Resolution in digital imaging is commonly defined by the number of pixels present in an image, with higher pixel counts representing higher-quality images. Early studies in telemedicine for burn injuries found that a modest image resolution of 800 × 600 pixels was sufficient for accurate image interpretation and that higher resolution images and larger file sizes were not required [48]. However, as technology has advanced, the standards for image resolution have evolved. In fact, the quality of camera technology in smartphones today far exceeds even what was available in high-end camera technology a decade ago.

As image quality increases however, so too does the file size. Though larger files contain more data and detail, file size can quickly become too large to send using standard telecommunications networks. To work around this, file size is often compressed during the process of image transfer to allow for quick and reliable image transmission. While image compression reduces file size, it also lessens image quality, particularly when employing standard compression methods typically used in telemedicine (i.e. JPEG) [50]. Roa et al. (1999) demonstrated that images may be compressed up to 50:1 while maintaining 90% accuracy in image assessment, though further compression reduced the accuracy of image assessment [49].

Photograph: 3-megapixel (MP) resolution with image compression not exceeding 20:1

Video: 640 × 360 resolution at 30 frames per second

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree