Technique for Treating the Crooked Nose

Ali Totonchi

Navid Pourtaheri

Bahman Guyuron

DEFINITION

A crooked nose is a nose with a portion of its midline structures deviating away from the facial midline along any extent of its cranial to caudal or anterior to posterior dimension.

ANATOMY

The crooked nose involves deviation or asymmetry of one or more structural components of the nose, including nasal bones, upper lateral cartilages, lower lateral cartilages, septum, and nasal spine.

PATHOGENESIS

The crooked nose may be a result of trauma, collapse or cicatrix after surgery, cocaine abuse, infection, mass effect from tumor, congenital defects, or improper development.

The crooked nose can affect nasal airway patency and sinus drainage in causing sinus or migraine headaches.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A complete patient history, including prior nasal and facial reconstructive or aesthetic procedures, should be reviewed.

It is essential to collect a history of nasal trauma, airway complaints, allergies, sinus symptoms, and headaches.

A crooked nose can be associated with sinus infections, sinus headaches and migraines, or nasal airway obstruction. Assessing for these factors and postoperatively tracking these symptoms aid in gauging the benefits of surgery beyond its aesthetic outcome.

Unilateral nasal airway obstruction that is persistent or obstructive symptoms during quiet and deep inspiration is a reliable indicator of mechanical airway compromise, such as an enlarged turbinate, septal or nasal deviation, or incompetent internal or external nasal valve that should be addressed during surgery. Cyclical nose obstruction is a physiological or occasionally pathological change that may not improve with surgery.

It is crucial to obtain a history of medications that can lead to bleeding (ie, aspirin and NSAIDs) and behaviors that may affect wound healing (ie, smoking, poor diet, steroid use). Discussion of these deleterious factors and their potential impact on postoperative outcomes with the patient may improve patient compliance.

Patient expectations should be assessed and managed, and the patient’s role in facilitating a successful outcome should be emphasized.

Physical examination should include facial analysis to assess for overall symmetry, canting of the occlusal plane, alignment of the nose with the rest of the face, and chin position in relation to the upper and the lower incisor midlines, lips, and upper face midline.

The nasal midline should be at the intercanthal midline rather than the intereyebrow midline, because patients often pluck their eyebrows differentially to align the midline of the deviated nose with the altered eyebrow.

Nasal analysis should assess each structural component and their degree of deviation. This should include observation of asymmetric nasal bones, a deviated caudal dorsum (septum and upper lateral cartilages), or a deviated nasal base (septum and lower lateral cartilages).

Midvault deviation always involves anterior septal deviation and is commonly associated with mid- and posterior septal deviation.

By tilting the patient’s head up for an examination of the basilar view, one can assess the deviation or asymmetry of the columella, tip, footplates, nostrils, and alar bases. An overhead view may detect the external nasal deviation more clearly. The most powerful view for observation of nose deviation is a full-smile frontal view.

Palpation to assess the three-dimensional frame of the nose could prove helpful:

One can palpate the nasal bones, upper lateral, and lower lateral cartilages, as well as the membranous septum, tip support, the caudal cartilaginous septum, and the anterior nasal spine. The latter is done by placing this structure between the dominant index finger and the thumb and confirming the midline positioning of this structure precisely.

Percussion over the frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses can elicit tenderness. This may be indicative of inflammation of the underlying sinuses.

To assess nasal valve competence or airway patency, one can occlude the patient’s nostril one side at a time and ask the patient to inhale normally and then deeply.

During the modified Cottle test, the examinee asks the patient to breathe quietly while supporting the nostril open at the level of the external and then internal nasal valve with a cotton-tip applicator or the speculum. If breathing is improved, this represents a positive test and indicates internal and/or external nasal valve incompetence.

An internal nasal exam using a speculum can detect septal deviation, enlarged turbinates, synechiae, perforation, spurs, and contact between the turbinates and the septum:

Septal deformities observed may include septal tilt, C- or S-shaped deviation in the anteroposterior or cephalocaudal dimensions, or localized deviation with septal spurs.

When there is a septal tilt, usually there is no curve to the septum, and the caudal septum is dislocated to one side of the vomer bone. This is the most common class of septal deviation, followed by C-shaped anteroposterior septal deviation.

Crusting, purulence, ulceration, or presence of polyps should also be noted.

It is important to observe and document the color and size of the turbinates—pale boggy turbinate mucosa may indicate allergic rhinitis, whereas erythematous mucosa may indicate infection or inflammatory rhinitis.

Analysis of the turbinates may reveal hypertrophy that typically occurs on the side ipsilateral to the external deviation or a paradoxical curl, which can misdirect the air and increase turbulence of airflow through the nose.

Analysis of the nasal valves and internal nose should be repeated before and after vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa using 0.25% phenylephrine or 1% ephedrine sulfate delivered via an aerosolized misting system or topically with cottonoid pledgets:

Posterior rhinoscopy is often helpful in patients with nasal airway obstructive symptoms.

Visualization of the posterior nasal airway is best achieved using a 0- or 30-degree nasal endoscope.

IMAGING

Life-sized photographic and cephalometric analysis should be performed to confirm the findings of the physical examination and allow for measurements used to plan for surgical correction, particularly on patients who are expecting aesthetic improvement.

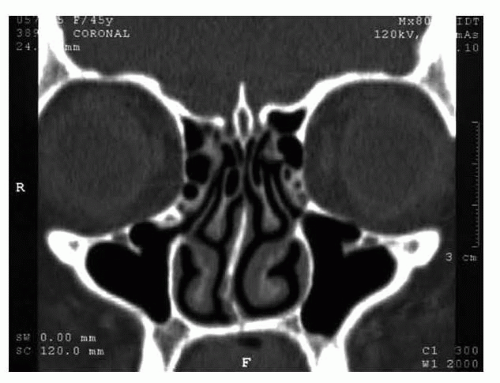

Computed tomographic (CT) imaging of the nose and perinasal sinuses is not obtained routinely but can provide valuable information in the following cases (FIG 1):

Patients with frequent sinus headaches, sinus infections, or migraine headaches

Patients for whom the extent of deviated structures are not clear after physical examination

Imaging provides clear visualization of the nasal bones, septum, turbinates, or a mass that may have contributed to the nasal deviation.

The CT may reveal many conditions such as septal deviation, large posterior spur sinusitis, concha bullosa, septal bullosa, Haller cell, and contact points.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The crooked nose usually presents with multiple deviated substructures, and successful surgical correction requires complete elimination of deviation from all substructures.

Surgical techniques for correction of the crooked nose will be discussed for each substructure of the nose that may be involved.

Preoperative Planning

Analysis of life-sized photographs and measurements of the deviation from the midline for each component of the nose can be valuable in correcting the deviation and discussing the surgical plan with the patient preoperatively. “Morphed” or simulated preoperative photos demonstrating the intended surgical changes can help the patient understand the surgical goals and manage the patient’s expectations prior to obtaining final written consent for the procedure. It is crucial to clearly indicate to the patient that there cannot be any guarantee that the simulated or intended results may not be achieved.

If there is a need for cartilage grafts, the first choice is septal cartilage as long as there is enough cartilage present. It is important to discuss with the patient the potential need for cartilage from a second site such as a conchal or costal graft if the septal cartilage is too deformed, absent, or insufficient to correct the nasal deformities planned.

Positioning

The patient is placed in supine position with the arms tucked by their sides.

After induction of general anesthesia, the airway is secured with dental floss or dental wire to the first premolar.

The table is turned 90 degrees away from anesthesia to optimize access to the face and nose.

The internal nasal hairs are trimmed with a pair of curved iris scissors, and the internal nose is cleansed with cotton swabs.

The entire face is prepped with Betadine solution. After 1 to 2 minutes, the Betadine is wiped away with sterile saline solution.

A split drape is placed sterilely around the face to expose the forehead up to the hairline and down to the chin.

This exposure allows for continual assessment of the nasal midline with respect to the facial midline and the effect of surgery on the upper lip position.

Approach

An open approach is the authors’ preferred method for correcting significant deviation or if other concomitant rhinoplasty maneuvers are planned.

Deviation of the upper nasal third or bony vault involves the nasal bones and will require osteotomies for correction.

Deviation of the midvault involves the septum and in most cases the upper lateral cartilages, which have to be separated from the septum and differentially trimmed after septoplasty and completion of nasal bone osteotomies. Other techniques, such as spreader grafts and/or septal rotational sutures, may be indicated.

Deviation of the lower nasal third or nasal base involves the lower lateral cartilages, and successful correction may require elongation of the short side, shortening of the long side, reshaping, and/or the use of cartilage grafts.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Administration of Local Anesthesia

It is important to achieve long-lasting and profound local anesthesia and vasoconstriction using the double-injection method:

Initial injection includes approximately 10 cc of 1% Xylocaine with 1:200 000 epinephrine solution.

If a turbinectomy is indicated, inject the turbinates using a 25-gauge spinal needle.

Cottonoid gauze saturated in oxymetazoline hydrochloride or phenylephrine solution is inserted deep in the nose as far cephalically and posteriorly as possible to produce vasoconstriction of the lining of areas that are difficult to reach with injection.

The injection should be performed with precision and in an organized manner, starting from the radix into soft tissues along the lateral and medial surface of the nasal bones profusely, along the medial surface of the nasal bones, followed by injection along the nasal base and columella, the dorsal septum on either side of the nasal roof, and the lining on either side of the vomer as far posteriorly as possible.

After a few minutes, the injection is repeated in the same order of initial injection using approximately 10 cc of 0.5% ropivacaine with 1:100 000 epinephrine.

This double-injection method starting with 1:200 000 solution reduces systemic uptake of the higher epinephrine concentration in the second injection that may otherwise cause hypertension, tachycardia, or arrhythmia. Ropivacaine in the second injection is longer lasting, which minimizes discomfort and the need for analgesics in the early postoperative period. Additionally, the initial injection by virtue of vasoconstriction renders the effects of the second injection more intense and produces protracted anesthesia.

▪ Nasal Bone Correction

Unilateral Nasal Bone Correction

Unilateral nasal bone deviation not affecting the internal nasal valve patency can be corrected with an onlay graft:

Septal cartilage (provides the most predictable outcome), conchal cartilage (gently crushed as a single or double layer), diced cartilage, soft tissue such as dermis, fascia graft, or fat injection may be used for this purpose.

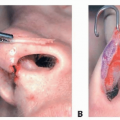

An intercartilaginous incision is made to expose the target nasal bone.

A limited pocket is created by elevation of the periosteum using a Joseph periosteal elevator.

The graft is positioned in the subperiosteal plane and molded into place.

The incision is loosely approximated to allow for drainage.

If the nasal bone shift is associated with medial transposition of the upper lateral cartilages, this may compromise ipsilateral internal valve function and requires correction by unilateral out-fracture.

A small vestibular incision at the pyriform aperture is made, and the periosteum is elevated using a Joseph periosteal elevator.

A low-to-low osteotomy and out-fracture of the nasal bone can be used to reposition the bone.

A spreader graft may be placed to avoid return of the nasal bone to its previous position as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree