Technique for Ptosis Correction

Nuri A. Celik

DEFINITION

There have been many procedures advocated for the treatment of the upper eyelid ptosis. Some of the techniques in the literature use incisional/excisional methods to deal with the levator mechanism failures.1

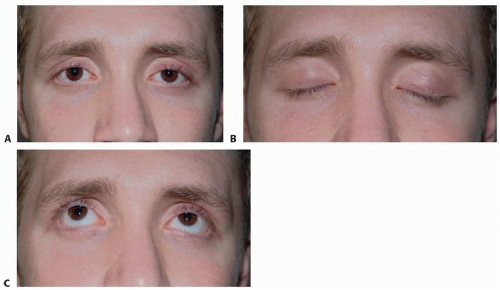

The technique described in this chapter relies solely on the preservation of the anatomical integrity of the levator system that is either stretched or detached because of various reasons. The key to using this technique is the presence of a good levator function. This is easily calculated by measuring the excursion of the upper eyelid during extreme upper and downward gaze (FIG 1).

Practically, any measurement above 10 mm is proper to use this technique efficiently. Iatrogenic or senile levator detachment patients are a different group, because they present with decreased levator function; however, in most cases, the system is intact to perform this type of correction. Fatty degeneration of the levator muscle is also a possibility with aging.

ANATOMY

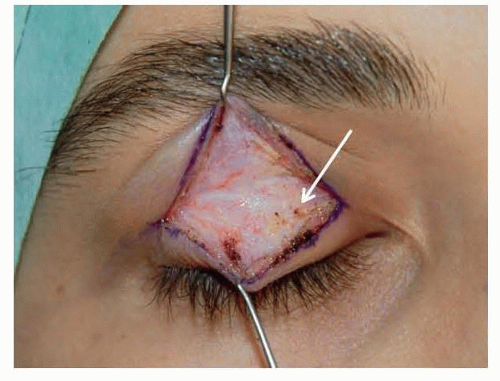

The upper eyelid is a complex structure that consists of multiple tissue layers that seem to adhere to each other around the upper anterior tarsal surface. When the skin and muscle layers are incised and a skin muscle flap is elevated as a superiorly based flap, one notices a thin layer of adipose tissue on top of the upper orbital septum that is more defined medially and somewhat less laterally (FIG 2). The increased convexity of the globe is possibly responsible from this uneven distribution of the fat layer. The underlying septum should always be incised laterally and higher than the upper tarsal border in order not to injure the levator mechanism inadvertently. There usually is a preaponeurotic fat pad present, if not previously excised or developmentally absent. Under the fat pad, toward the upper orbital rim, one can find the vertically oriented fibers of the levator muscle. The surgeon should always keep in mind that immediately under the levator aponeurosis, there is the vertically oriented arterial loop of the supratarsal arch that might resemble the fibers of the levator muscle, for untrained eyes, that might be difficult to differentiate.

PATHOGENESIS

Periorbital aging is a very complex phenomenon. Twelve percent of the patients in Dr. Lambros’ series had upper eyelid ptosis; however, there is no reference to frontalis activity in his patient population.2 Increased frontal muscle activity is a common finding in the elderly population and usually is a compensation for a ptotic upper eyelid. The original percentages of upper eyelid ptosis should be higher in the aging population due to the weakening of the levator attachments or stretching of the aponeurosis.

There are still some centers that use incisional and excisional surgical methods on the levator mechanism. It is very important not to distort the anatomy of the levator system.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

In younger patients, when present, ptosis is a significant complaint because a higher upper eyelid arch is the norm in early decades of life.

Asymmetric cases are easily diagnosed.

In senile ptosis, most of the time, the patient is not aware of the problem if it is bilateral. Senile ptosis takes a long time to advance, and by that time, compensatory mechanisms such as frontalis hyperactivity develop (FIG 7).

An occasional patient might complain about transverse wrinkles as a result of the long-standing frontalis muscle contraction.

The anatomy of the brow-upper eyelid interface changes in ptosis patients. If there is no skin excess to camouflage the superior sulcus, this area appears hollow (FIG 8). The supratarsal crease-eyelash margin distance is increased, and the upper eyelid covers more than 2 mm of the upper limbus. In elderly cases, brow ptosis and skin excess disguise the deformity, and supratarsal crease might appear to be of proper dimension. In these cases, elevating the eyebrows will reveal the underlying pathology (FIG 9). A meticulous preoperative assessment and planning ensure symmetric eyelid levels and supratarsal crease distances.3 The superior sulcus fullness should also be evaluated separately on both sides, and upper eyelid fat manipulation should be taken into account in order to achieve a satisfactory outcome (FIG 10).

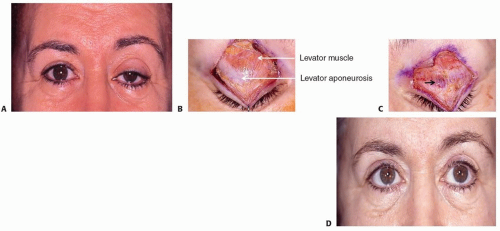

FIG 4 • A. A 64-year-old patient seen following a cyst removal from the left upper eyelid. She has left frontalis muscle hyperactivity due to left eyelid ptosis, an increased supratarsal distance. B. Intraoperative findings of the patient. The upper orbital septum is opened, and the preaponeurotic fat pad is retracted to expose the levator system. The right upper eyelid shows a normal anatomy of levator muscle and mechanism. C. The left upper eyelid levator aponeurosis has a significant injury medially, which possibly caused complete detachment of the system resulting in upper eyelid ptosis. D. One year after treatment with a levator advancement technique, she had bilateral blepharoplasty to equalize the supratarsal fold and correct the left ptosis. However, the frontalis muscle hyperactivity is not completely resolved.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access