Syphilis: Introduction

|

Syphilis is an infection caused by Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. It can cause serious disease in persons who acquire it after birth and especially devastating disease in persons who acquire it in utero. Many of its manifestations are cutaneous, making it of interest and importance to dermatologists, especially as morbidity from syphilis rises in the developed world and continues in the developing world.

History

Whether syphilis arose in the New World, the Old World, or both remains a controversial subject.1–3 Pandemics of syphilis began in the Old World in Naples, Italy, 1 year after Columbus returned from the New World.2,4,5 Syphilis was much more virulent then, earning it the monicker “great pox,”4 to distinguish it from another virulent disease with cutaneous manifestations, smallpox. The disease takes its name from a poem, called Syphilis, Sive Morbus Gallicus (Syphilis, or the French Disease), written in 1530 by Giralomo Fracastoro, a physician and poet of Verona. Part of the poem recounts the story of a shepherd, named Syphilus, who, as punishment for angering Apollo, was afflicted with the disease known as syphilis.5 Other names besides Morbus Gallicus and the Great Pox by which the disease has been known include lues, the Great Mimic, the Great Masquerader, the Great Imitator, and the Neapolitan disease.5 The cause of syphilis, the bacterium T. pallidum, was discovered by Schaudinn and Hoffman in 1905.6 Darkfield microscopy and serologic testing for syphilis were pioneered, respectively, in 1906 by Landsteiner and in 1910 by Wasserman.4

Syphilis historically has been of major interest to dermatologists, who were leaders in syphilis research and treatment in Europe and the United States.7–12 One of the leading American dermatology journals, currently called Archives of Dermatology, was before 1955 called Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology. An editorial explaining the jettisoning of “Syphilology” from the journal’s title stated as follows:

The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. The papers on syphilis that are now submitted to the Archives are few and far between. Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, “Syphilology,” on this publication seems no longer warranted.

Elsewhere in the world, however, the link between dermatology and syphilology (and other sexually transmitted diseases) remains stronger.13,14

Treatments for syphilis in the prepenicillin era included burning sores with hot irons, rubbing mercury-containing ointments on lesions and other parts of the body, administering mercury orally, and treating with arsenicals, including salvarsan (also called “606” or arsphenamine), which was discovered by Ehrlich and Hata in 1909.4 Heat treatments were also used. Recognition that T. pallidum was heat sensitive led the Viennese psychiatrist Julius Wagner von Jauregg to develop syphilis malariotherapy in 1917,15 an accomplishment for which he received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1927.16 That therapy involved inoculating syphilis patients with malaria, allowing them to experience, optimally, between 10 and 12 febrile episodes, and then treating them with quinine.10,16–18 The treatment reportedly led to complete or partial remission of general paresis in a substantial proportion of patients, though it killed an estimated 10% of those receiving the therapy.17 Heat therapy through malaria inoculation and through other means was practiced in the United States until the early 1950s, when use of penicillin became widespread.10

Two studies have provided the most insight into the natural history of syphilis. The first was a retrospective study of approximately 2,000 persons with syphilis in Oslo, where mercury treatments standard in other places were not used.18 The second was the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, in which 399 black men with late syphilis from Alabama were prospectively followed from 1932 to 1972.19 The men were denied treatment for syphilis, even after the discovery of the effectiveness of penicillin for the disease. There were multiple other serious ethical lapses in the study. The aftermath of the study lead to major changes in ethical requirements for conducting clinical research in the United States.20

In addition to being more virulent than it is currently, syphilis was also much more common. Of historical interest, persons said to have suffered from syphilis include Ivan the Terrible, Henry VIII, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Al Capone,4 and among many others.21 Osler, aware of the high prevalence and protean manifestations of syphilis, has been quoted as saying “He who knows syphilis knows medicine.”4 By the early 1930s, it was estimated that approximately 10% of Americans had syphilis, with 500,000 new infections and 60,000 cases of congenital syphilis per year.22 In 1937, Sugeon General Thomas Parran, keenly interested in syphilis, published a book, titled Shadow on the Land,23 that focused on the substantial public health harms of the then-prevalent disease.22 Parran prioritized syphilis prevention and control, emphasizing screening, treatment, community involvement, and education.22,24 Nevertheless, syphilis remained prevalent until penicillin, discovered by Fleming in 1928 and first used to treat syphilis in 1943, became widely available in the postwar era.4 Syphilis incidence then declined sharply in the 1950s, followed by a modest rebound through the mid-1980s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s syphilis reemerged in the United States in the South and in large cities, disproportionately affecting black Americans.2,25 Incidence then fell to a postwar nadir in 2000, when 5,979 cases (2.1 cases per 100,000 residents) of primary and secondary syphilis were reported nationally. As syphilis incidence waned, CDC released the National Plan to Eliminate Syphilis from the United States in 1999.26

Epidemiology

Unfortunately, syphilis incidence in the United States began increasing in late 2000, and that increase has continued nationally through 2009.2,27 The current syphilis epidemic in the United States and other parts started, and has continued, primarily among men who have sex with men (MSM).2,28 Incidence of syphilis and other sexsually transmitted diseases (STDs) among MSM had declined during the AIDS epidemic, and the subsequent increased incidence among MSM has been attributed to a number of factors, including a decrease in safe sex practices resulting from successful HIV treatments, use of the Internet to meet sex partners, serosorting (i.e., attempting to choose sex partners who share the same HIV status), and an increase in use of recreational drugs, including methamphetamine and erectile-dysfunction medicines.2,28,29 Of all primary and secondary syphilis cases reported to CDC during 2009, 2% occurred in MSM,27 of whom an estimated 30%–74% were coinfected with HIV.27,29 The male-to-female rate ratio for primary and secondary syphilis cases, which measures the extent to which transmission is occurring among MSM, was 5.6 in 2009, an increase compared with 1.2 in 1996 and 5.1 in 2008.27 The male-to-female rate ratio varies greatly geographically, however, being generally lower in the South and higher in larger cities nationwide. Outbreaks among heterosexual men and women continue to occur sporadically,30,31 and syphilis among heterosexuals has reemerged as a public health problem.31 Compared to persons who have never had syphilis, Persons with a history of syphilis are at increased risk of repeat syphilis.32,33

In 2009 44,828 cases of syphilis overall were reported to CDC, a 3% decrease from 2008.27 Those included 13,997 primary and secondary cases (4.6 per 100,000 residents) as well as 13,066 early latent cases and 17,338 late and late latent cases. Ten of the 13 states with rates of primary and secondary syphilis greater than the national average (4.6/100,000 population) were in the South, which accounted for 53% of primary and secondary cases nationwide in 2009. The other three states were New York, California, and Illinois. The rate in the District of Columbia, which reported 163 cases in 2009, was 27.5, higher than that of any state. Of those counties and independent cities that accounted for 50% of reported primary and secondary syphilis cases in 2009, Los Angeles had the highest number of cases (768) and Jefferson County, Texas, had the highest rate (65.0/100,000 population). Rates of primary and secondary syphilis nationwide were highest in persons 20–29 years old. Blacks are disproportionately affected by primary and secondary syphilis, with rates over nine times higher than rates among non-Hispanic whites in 2009 overall, including 8 and 20 times higher among black males and females, respectively, compared with white males and females.27 In 2009, there were 427 reported cases of congenital syphilis in the United States.27 The incidence of congenital syphilis increased 22% from 2005 to 2009, concurrent with an increase in the rate of primary and secondary syphilis among females. Rates have increased primarily in the South and among infants born to black mothers.34

Based on those epidemiologic data and other factors, the CDC recommends screening (i.e., testing of asymptomatic persons) for syphilis in the United States for the following groups38:

- MSM who have been sexually active within the past year at least annually, and more frequent screening (every 3-6 months) for MSM with multiple or anonymous partners or who have sex in conjunction with illicit drug use (particularly methamphetamine use) or whose partners have sex in conjunction with those activities;

- Pregnant women, at the first prenatal visit, and early in the third trimester for women who are at high risk for syphilis, live in areas of high syphilis morbidity, or are previously untested;

- Persons in correctional facilities, if syphilis screening is justified on the basis of epidemiology in the locality and in the correctional institution.

Internationally, morbidity from syphilis remains substantial. Each year an estimated 12 million new cases of syphilis occur, and 1 million pregnancies are complicated by syphilis.2

Biology and Pathophysiology

Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum is a motile, spiral-shaped bacterium for which humans are the only natural host.16 T. pallidum ranges in size from 5 to 16 μm in length and is 0.2 to 0.3 μm in diameter.35 (Fig. 200-1) The bacterium is surrounded by a cytoplasmic membrane, which is itself enclosed by a loosely associated outer membrane. Between those membranes lies a thin layer of peptidoglycan, which provides structural stability and houses endoflagella, organelles that are responsible for T. pallidum’s characteristic corkscrew motility. Microscopically the bacterium is indistinguishable from other pathogenic treponemes that cause nonvenereal diseases, including T. pallidum subspecies endemicum (bejel), T. pallidum subspecies. pertenue (yaws), and T. pallidum subspecies carateum (pinta). The T. pallidum genome, sequenced in 1998,36 is 1.14 Mb in length, relatively small for a bacterium.16

The bacterium has very limited metabolic capabilities, making it reliant on host pathways for many of its metabolic needs.16,37 T. pallidum does not survive more than a few hours to days outside its host and cannot be cultured in vitro for sustained periods, complicating efforts to understand the organism.16,37 Instead, it must be propagated in mammals, with rabbits the preferred species because, following testis inoculation, rabbits experience disease manifestations,37 unlike mice.16 T. pallidum divides slowly, taking from 30 to 50 hours in vitro. That slow reproduction rate has important implications for treatment, which must be present in the body for a long period in order to assure effectiveness against the bacterium.38

Following inoculation, T. pallidum attaches to host cells, including epithelial, fibroblast-like, and endothelial cells, likely by binding to fibronectin, laminin, or other components of host serum, cell membranes, and the extracellular matrix. It can invade rapidly into the bloodstream—within minutes of inoculation, based on rabbit models—and can cross many barriers in the body, such as the blood–brain barrier and the placental barrier, to infect many tissues and organs. That dissemination leads ultimately to manifestations of syphilis distant from the site of the initial chancre(s) in an infected person and in a developing fetus.

T. pallidum lacks virulence factors common to many other bacteria, including lipopolysaccharide endotoxin.16 It does, however, produce a brisk immune response, mediated by membrane lipoproteins,39 that begins shortly after infection. Infection at all stages leads to infiltration by lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells.37 CD4+ T cells predominate in chancres, and CD8+ T cells predominate in lesions of secondary syphilis.37 Infection leads also to elaboration of Th1 cytokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ, although downregulation of the Th1 response during secondary syphilis, coincident with the peaking of antibody titers,37 might contribute to the organism’s ability to evade the host immune response.40,41 Subtyping studies of T. pallidum have linked certain strains of the organism to neurosyphilis.42

The humoral immune response begins with production of IgM antibodies approximately 2 weeks after exposure, followed 2 weeks thereafter by IgG antibodies.39 IgM in addition to IgG continues to be produced during infection and can lead to immune-complex formation.39 Antibody titers peak during bacterial dissemination, in secondary syphilis.37 Some antibodies crossreact with other treponemal species, and some are specific for T. pallidum subspecies pallidum. The immune response is somewhat active against the organism, helping block attachment of the organism to host cells, conferring passive immunity in rabbit models, and enhancing phagocytosis in vitro.37

The immune response is sufficient to prevent syphilis reinfection in persons who have untreated syphilis. In other words, in what is called Colles’ law or “chancre immunity,” persons with untreated syphilis will not experience another episode of primary syphilis as long they remain untreated.37 However, the immune response is insufficient to eradicate T. pallidum from the host. In addition to suppressing the Th1 response, the organism is thought to evade those host defenses by taking harbor in immune-privileged tissues (e.g., central nervous system, eye, and placenta), failing to be present in sufficient quantities (e.g., during latent infection) to trigger a host response, varying its surface proteins during infection through gene conversion, and overcoming host attempts to prevent bacterial access to iron, which is necessary for bacterial growth.16,37 The immune response is also not adequate to prevent reinfection after a person is cured of syphilis, although it might modify the course of reinfection. Compared with persons with syphilis for the first time, for example, reinfected persons are less likely to have manifestations of primary or secondary syphilis and more likely to be diagnosed with latent syphilis.43

The immune response is also likely responsible for the tissue damage caused in syphilis.16 Damage to axons located near the site of a chancre might explain why that lesion, although ulcerative, is typically painless.44

Interest in a vaccine for syphilis continues, with focus on using outer membrane protein antigens to elicit an immunoprotective response.45 However, a number of barriers to vaccine development exist. Those include variability in outer membrane protein antigens, the limited number of antigens on T. pallidum to which immunoprotective antibodies could bind, the possibility that the formation of a host protein coat around T. pallidum might prevent antibody binding, and a potential lack of commercial incentive to produce a vaccine.45

Clinical Course

The natural history of syphilis is presented in Table 200-1. Of note, when considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis in a patient, clinicians must consider the epidemiology and routes of transmission of the disease. That requires taking a complete sexual history, including ascertaining genders of sex partners and the types of sexual behaviors engaged in with those partners.46 From a clinical perspective specific behaviors with specific partners are more important than sexual orientation (e.g., gay or straight), because some persons who engage in same-sex sexual behavior do not self-identify as gay.47

Contact (⅓ become infected) ↓ (10–90 days) Primary (chancre) ↓ (3–12 weeks) Secondary (mucocutaneous lesions, organ involvement) ↓ (4–12 weeks) Early latent → Relapsing (1/4) (1 year from contact) ↓ | |

Late latent (more than 1 year) |  |

Remission (⅔) | Tertiary (⅓) Late benign (16%) Cardiovascular (10%) Neurosyphilis (5–10%) |

Syphilis is most commonly acquired sexually, when a person comes in contact with infectious lesions of syphilis on another person. Infectious lesions of syphilis in adults, which include chancres, condyloma lata, and mucous patches, can be present anywhere on the body but are typically located in or around the genital, anal, or oral area. Direct contact with infectious lesions during oral, vaginal, or anal sex, or during other sexual activities, can result in inoculation and infection. Lesions on keratinized skin (e.g., palmoplantar lesions and maculopapular rash on the trunk) typically do not contain sufficient treponemes to be infectious, and prophylaxis for persons exposed to noninfectious lesions such as those is neither necessary nor indicated. Infectious lesions of congenital syphilis includes discharge from rhinitis (“snuffles”) and bullous lesions on the skin.

Syphilis can also be acquired through nonsexual contact,48 blood transfusion,49 accidental inoculation in an occupational setting (e.g., laboratory or healthcare worker50) or nonoccupational setting (e.g., tattooing51), or through exposure in utero.52

Estimates of the risk of acquisition of syphilis following exposure to a person with infectious syphilis are varied and have been derived in two types of sources.53 The first source are data from three prospective placebo-controlled trials of prophylactic treatment, in which 9%,54 28%,55 or 63%56 of contacts to syphilis acquired syphilis. The second source is from studies of persons identified as sex contacts in contact-tracing interviews of persons diagnosed with syphilis, in which 18%–88% of contacts acquired syphilis.53 Nevertheless, the relatively high estimates of syphilis acquisition following exposure underscores the importance of prompt treatment and testing of sex contacts, as discussed later in this chapter. Persons recently exposed to and infected with syphilis who have yet to manifest signs or symptoms of the disease are said to have incubating syphilis.

As defined by CDC surveillance case definitions, primary syphilis is a stage of syphilis characterized by one or more chancres, in the presence of laboratory evidence from tissues or sera consistent with syphilis.57 As with all CDC syphilis surveillance case definitions presented in this chapter, classification by a clinician with expertise in syphilis may take precedence over surveillance case definitions.57

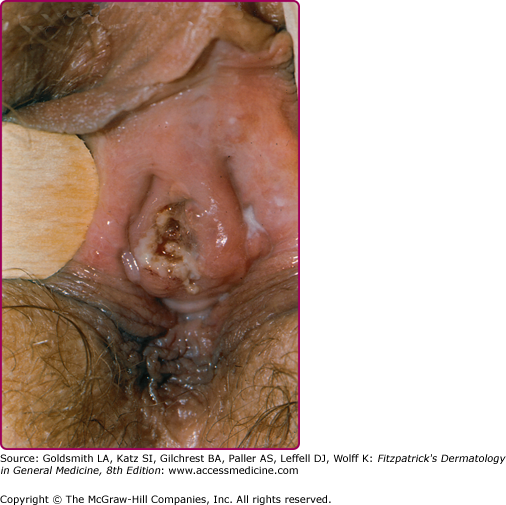

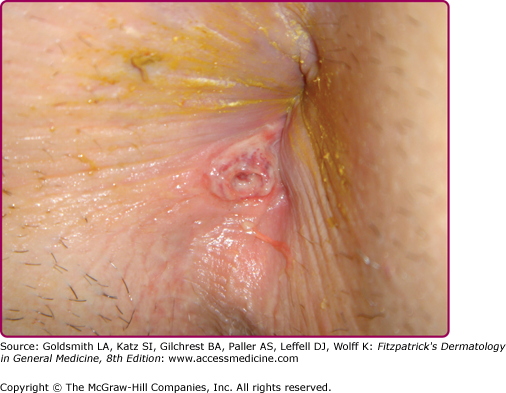

At the inoculation site, a chancre develops after an incubation period that ranges from 10 to 90 days (average, 3 weeks). The chancre starts as a dusky red macule that evolves into a papule and then a round-to-oval ulcer (Figs. 200-1 and 200-2). The typical chancre, also called a Hunterian chancre or “ulcus durum” (hard ulcer), ranges in diameter from a few millimeters to 2 cm and is sharply demarcated with regular, raised borders that are indurated, giving the lesion a cartilaginous feel. The base is usually clean, and the chancre is classically not painful. Up to 35% of chancres, however, are reportedly painful,58 and multiple chancres (Figs. 200-3 and 200-4) have been reported in 32%–47% of cases.59 The absence of any of the typical features of a chancre does not rule out syphilis, however. Variations in clinical presentation can result from the number of spirochetes inoculated, the patient’s immune status, concurrent antibiotic therapy, and impetiginization.40,60,61 Patients might not be aware of chancres, especially if painless and located in areas that are not visible, such as the anus, vagina, cervix, or oral cavity.62

Common genital locations for a chancre in men include the glans, the coronal sulcus, and the foreskin.62,63 Retraction of the foreskin when a chancre is present on the underside causes the foreskin to flip suddenly, a sign known as the dory flop, after the movement of a dory, a small wooden fishing boat, which flips suddenly when overturned.63,64 The dory flop sign can help distinguish chancres from other nonindurated causes of genital ulcer disease, such as herpes simplex virus infection and chancroid, that present without the induration that leads to the sudden flip of the foreskin. Uncommon presentations include giant necrotic chancre, phagedenic chancre (a deep, bright-red, necrotic ulcer with a soft base and exudate, resulting from secondary bacterial infection associated with immunosuppression), phimosis resulting from adherence of a chancre on the foreskin to the glans, and balanitis.65

Common genital locations in women, in decreasing order, include the cervix, labia majora, labia minora, fourchette, and urethra (Fig. 200-5).66 Chancres in women can be more edematous than indurated.63 Edema indurativum is a unilateral labial swelling with rubbery consistency and intact surface, indicative of a deep-seated chancre.

Extragenital chancres in many areas of the body have been reported.67,68 Oral sex was identified as the likely mode of syphilis acquisition in 14% of cases overall, and in 20% of cases in MSM, in Chicago during 1998–2002.69 Other studies have attributed even higher proportions of infections among MSM to exposures during oral sex.70 Anal sex can lead to development of chancres in the perianal (Fig. 200-6) or anal areas that can be difficult to detect on routine physical examination.58,71 Digital or other72,73 contact with the oral, genital, or anal areas or receiving a bite (e.g., on the nipple during sex74) can also lead to infection.

The chancre heals in 3–6 weeks without treatment and 1–2 weeks with treatment. Scarring typically does not occur, although thin atrophic scars may occur.62 Coinfection with herpes simplex virus or Haemophilus ducreyi, the causative organism of chancroid, can be present in rare cases.75–77 Relapses of primary syphilis, called monorecidive syphilis or chancre redux, arise in the setting of untreated or inadequately treated syphilis and are rare.78

In 60%–70% of cases of primary syphilis, painless regional lymphadenopathy arises 7–10 days after the chancre appears, especially when the chancre’s location is genital. Unilateral lymphadenopathy is more common earlier in the course of disease, with bilateral involvement later in the course.78

A differential diagnosis for chancres is presented in Box 200-1.

INFECTIOUS

|

NON-INFECTIOUS

|

As defined by CDC surveillance case definitions, secondary syphilis is a stage of syphilis characterized by localized or diffuse mucocutaneous lesions, often with generalized lymphadenopathy, in the presence of laboratory evidence from tissues or sera consistent with syphilis. The chancre may still be present.57

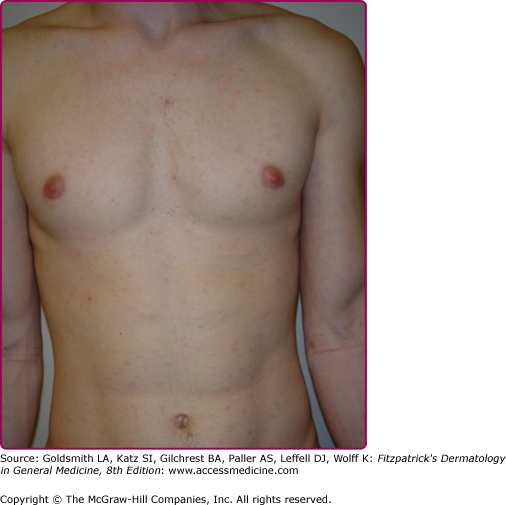

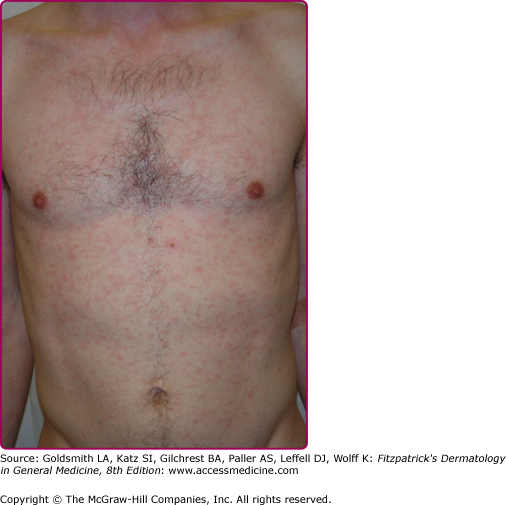

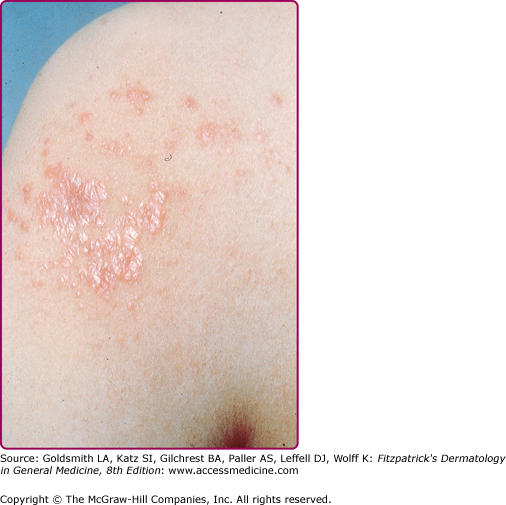

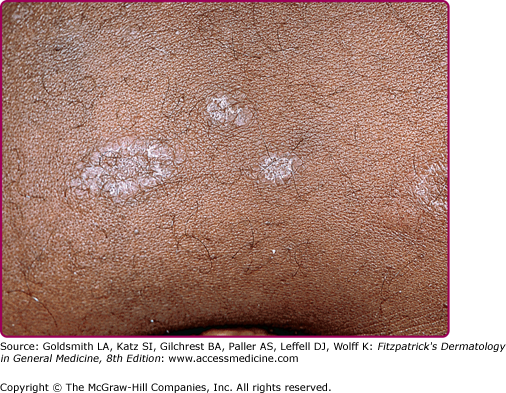

Lesions of secondary syphilis, classically called “syphilids” or, when affecting the skin, “syphiloderms,”63 typically erupt 3–12 weeks after the chancre appears (up to 6 months after exposure). In up to 25% of cases lesions of the secondary syphilis develop while the chancre is still present59,61 (Figs. 200-7 and 200-8), with overlap more common among HIV-infected persons.61 Rash is present in nearly all cases of secondary syphilis, although the specific type of rash varies.59,60,79 Erythematous macules (roseola syphilitica) or maculopapules are commonly present symmetrically on the trunk and extremities in 40%–70% of cases (Fig. 200-10), with papular, papulosquamous, or lichenoid (Fig. 200-11) presentations less common.59,79 A white scaly ring on the surface of papulosquamous lesions, called Biette’s collarette (Fig. 200-12), is characteristic but not pathognomonic for syphilis. The face is typically spared in these generalized syphilids, although seborrheic dermatitis-like lesions around the hairline, termed the Crown of Venus or corona veneris, can form a crown-like pattern.62 Lesions are not usually pruritic,63 although pruritus was reported in up to 40% of patients in one study.63 The presentation of the rash overall can be subtle or florid, or can develop from subtle macules to more florid papules over time.80 Erythematous to copper-colored round papules, well demarcated and sometimes with an annular scale, are present on the palms and soles in nearly 75% of cases (Figs. 200-13A and 200-13B).59 Plantar lesions can be variously mistaken for calluses (clavi syphilitici). Plantar lesions can also extend to the lateral and posterior aspects of the foot (Fig. 200-14).

Figure 200-8

Plantar lesions of secondary syphilis in a man who also had a penile chancre (see Fig. 200-7).

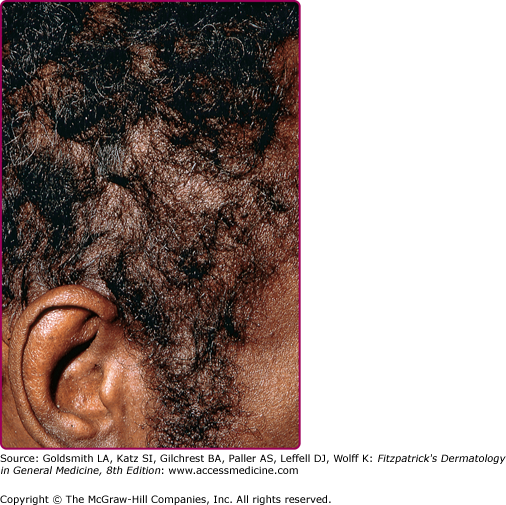

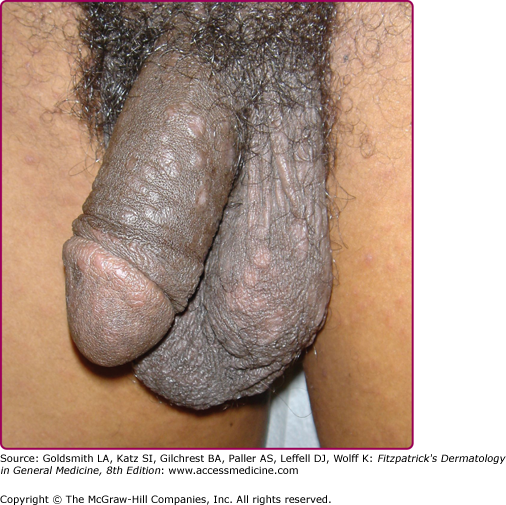

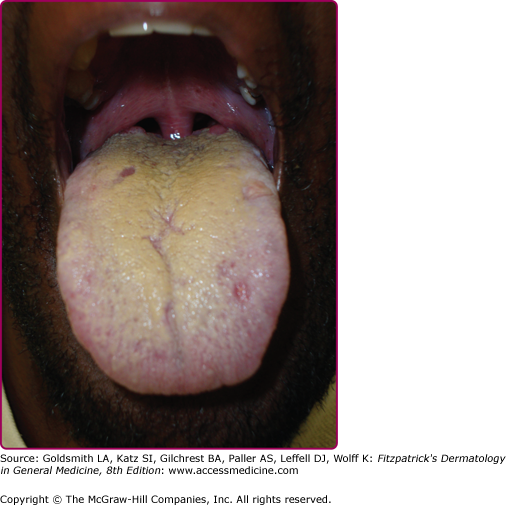

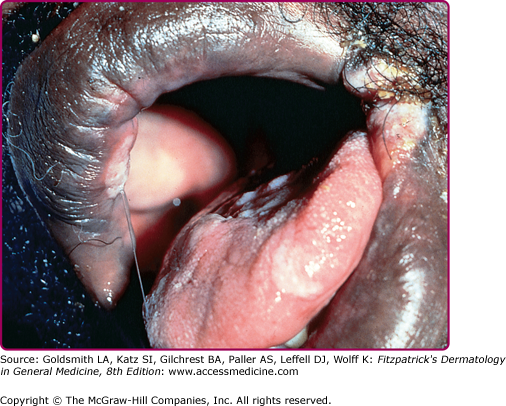

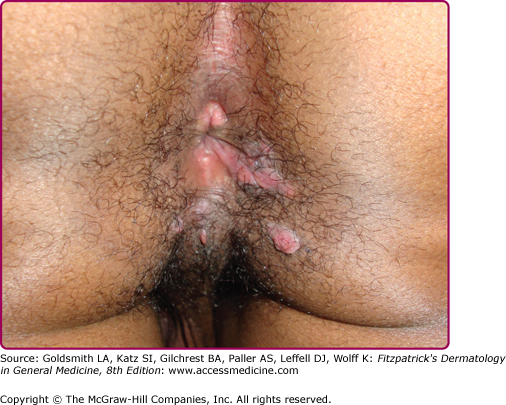

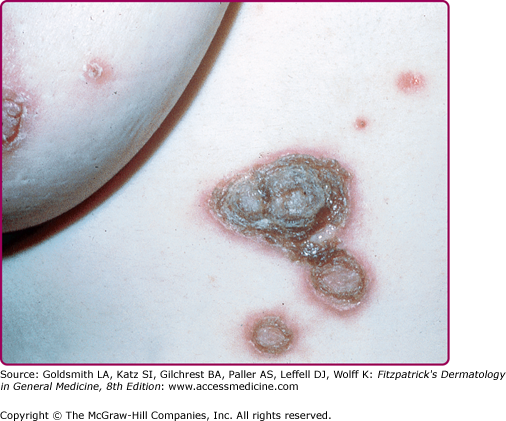

Other dermatologic manifestations include a patchy nonscarring alopecia, described as “moth-eaten” (Fig. 200-15) or, less commonly, a diffuse alopecia of the scalp. Loss of lateral third of the eyebrows can occur. Annular papules and plaques can be present around the mouth and nose, in a presentation colloquially referred to as “nickels and dimes”63 (Fig. 200-16). Papules and plaques, sometimes annular and occasionally papulosquamous, can also be present on the penis and scrotum (Figs. 200-17 and 200-18). Mucous patches are white-to-yellow erosions on the tongue that efface lingual papillae63 (Fig. 200-19). Confluence of mucous patches on the tongue has been termed plaques fauches en prairie. Mucous patches can be present elsewhere in the oral cavity, on other mucous membranes, or at the corners of the mouth, where they appear as “split papules,” with an erosion traversing the center (Fig. 200-20). Mucous patches are teeming with spirochetes and, hence, highly infectious. Also highly infectious are condyloma lata, which present as moist, flat, well-demarcated papules or plaques with macerated or eroded surfaces in intertriginous areas, commonly in the labial folds in females or in the perianal region in all patients63 (Figs. 200-21 and 200-22). However, any moist intertriginous area of the body can harbor condyloma lata, including the axillae, web spaces between toes, and the folds under breasts or an abdominal panniculus. Mucous patches and condyloma lata have been reported in 8% and 17% of patients with secondary syphilis, respectively.59 Malignant lues is a rare manifestation that presents as crusted or scaly papules and plaques that can ulcerate or become necrotic, with an oyster shell-like surface (Fig. 200-23). These lesions, described as rupioid, are often seen in association with high nontreponemal titers and systemic symptoms.81 Nail changes including fissuring, onycholysis, Beau’s lines, and onychomadesis have been reported.62 Less common presentations of secondary syphilis include lichenoid, nodular, follicular, pustular, framboesiform, and corymbose eruptions and palmoplantar keratodermas.65,82–85 With the exception of mucous patches and condyloma lata, cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis do not contain a substantial number of treponemes and, therefore, are not typically infectious.

The maculopapular rash of secondary syphilis can resemble almost any generalized or localized maculopapular eruption (Box 200-2); mucous membrane lesions resemble mucosal manifestations of other dermatoses, and syphilitic hair loss has to be separated from other etiologies of alopecias.

Most Likely

Consider

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree